Spatial working memory is a neuropsychological function of special interest in schizophrenia. First, nonhuman primate and human studies have demonstrated that spatial working memory processes rely on intact functioning of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

(1,

2), an area associated with core deficits in schizophrenia. Second, studies that have evaluated spatial working memory using a variety of spatial delayed-response paradigms have demonstrated impairments in patients with schizophrenia

(3,

4). Third, persons at risk for the illness demonstrate impairments in spatial working memory, including first-degree biological relatives

(5) and high-risk adolescents who later develop schizophrenia

(6), indicating that spatial working memory may be an endophenotype for schizophrenia. Fourth, spatial working memory deficits are associated with impaired community functioning, including work

(7). Thus, spatial working memory taps neural processes that are of fundamental interest in schizophrenia, and impairments may indicate risk for illness and impaired community function.

Spatial working memory performance is also of interest in the evaluation of medications because it is altered by drugs commonly used in the treatment of schizophrenia. For example, in a 4-week, double-blind, randomized trial, risperidone improved, while haloperidol worsened, spatial working memory performance, an effect largely due to coadministration of benztropine with haloperidol

(8). Because clozapine exhibits potent antimuscarinic activity in vitro at a magnitude similar to that seen with benztropine

(9,

10), it may exert a deleterious effect on spatial working memory. Such an effect is suggested by impairment in visual memory

(11,

12) and verbal working memory

(13) during clozapine treatment. A more recent controlled trial comparing clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol

(14) indicated that verbal working memory and visual memory were unchanged from baseline in patients receiving clozapine and risperidone. Spatial working memory was not evaluated.

In addition, nonhuman primate studies have demonstrated that spatial working memory is impaired by D

1 antagonists and improved by D

1 agonists

(15), indicating that spatial working memory is modulated, in part, by prefrontal dopaminergic processes. Thus, beneficial effects of risperidone compared with haloperidol on working memory

(16) may be due to both its relative lack of anticholinergic properties

(8,

17) as well as its ability to enhance dopamine activity in the prefrontal cortex

(17).

The current study evaluated the effects of clozapine and risperidone on performance of a computerized assessment of spatial working memory in patients with moderately refractory schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. It was hypothesized that relative to clozapine, risperidone would improve spatial working memory.

Method

This study was part of a larger 6-month, multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial comparing clozapine (target dose: 500 mg/day) and risperidone (target dose: 6 mg/day) in patients with moderately treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Clinical and adverse event data have been reported elsewhere (unpublished study of N.R. Schooler et al.). Subjects treated with clozapine were less likely to discontinue treatment for lack of efficacy (15%) than those treated with risperidone (38%) and showed more improvement globally and in asociality. Other reasons for discontinuation included withdrawal of consent and treatment-related side effects. However, the proportion of subjects meeting an a priori criterion of psychosis symptom improvement (20% improvement on at least one of four psychotic symptoms) did not significantly differ between the two groups (risperidone: 57%; clozapine: 71%). A previous report of this study indicated no medication effects on social competence or problem solving

(18). All subjects provided informed written consent for their participation.

Subjects

Study participants met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as determined by a diagnostic checklist based on a structured interview. Subjects’ illness had shown evidence of treatment resistance, defined as at least one trial of a conventional antipsychotic at a dose equivalent to 600 mg/day of chlorpromazine, a second trial of a different conventional antipsychotic at a dose equivalent to 250–500 mg/day of chlorpromazine, and at least a moderate severity score on one of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(19) psychotic symptom subscale items or on one of the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms

(20) global subscales. Last, subjects were 18–60 years of age and were living in the community or judged potentially dischargeable from the hospital. Exclusion criteria were diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome with recurrence upon rechallenge, history of CNS pathology, pregnancy, or mental retardation that precluded understanding study participation or assessment procedures.

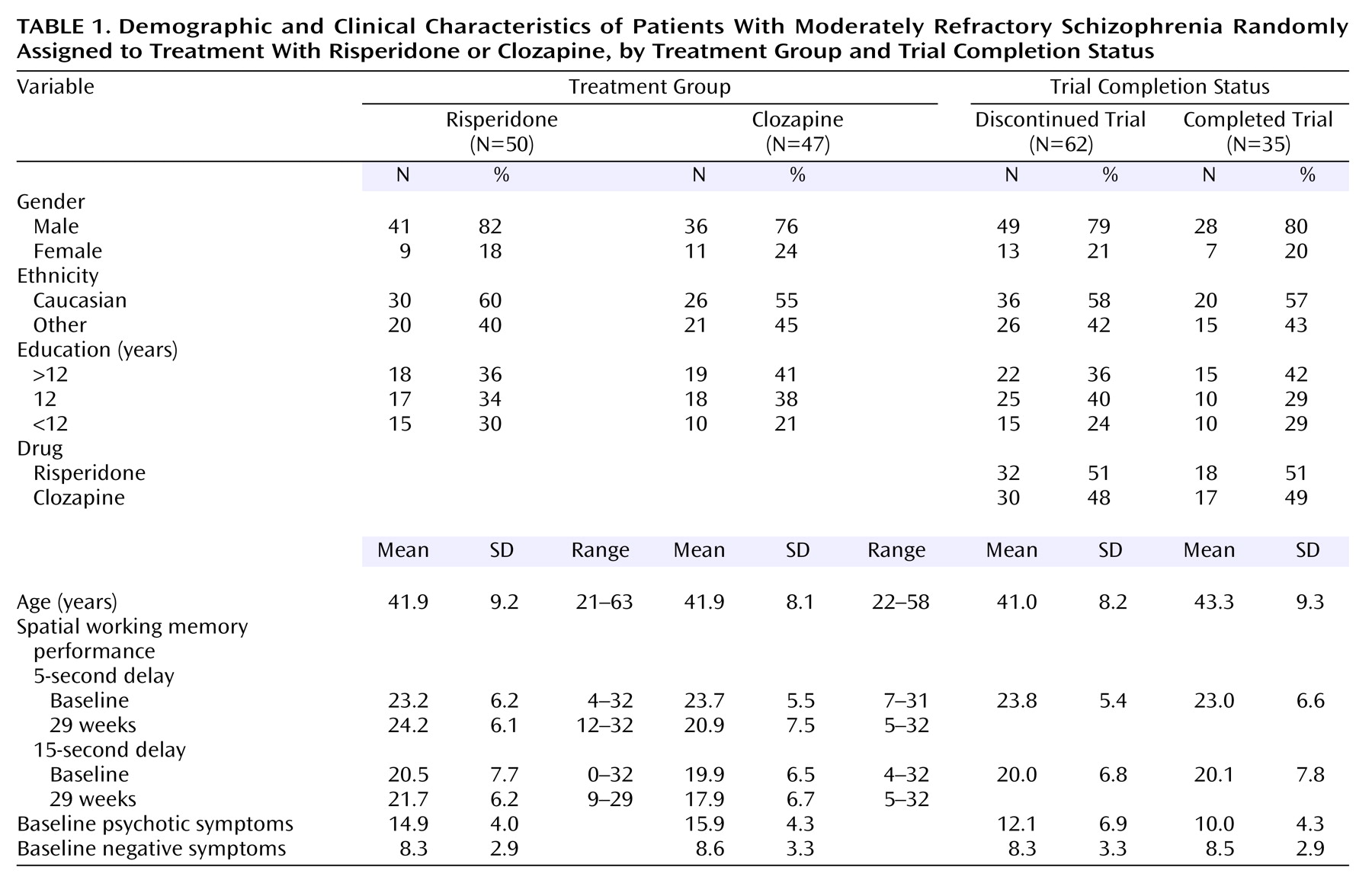

Of the subjects recruited for the parent study (N=107), 97 completed baseline spatial working memory tests. Fifty subjects were randomly assigned to treatment with risperidone, and 47 received clozapine. Demographic variables (age, gender, education, ethnicity) by drug group are presented in

Table 1.

Assessments

The BPRS was used to assess clinical symptoms. Composite scores of the psychotic symptom subscale (hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness, and conceptual disorganization) and the negative symptoms anergia subscale (emotional withdrawal, blunted affect, motor retardation) were used in statistical analyses.

Spatial working memory was measured using a computerized delayed response test

(8) imposing one of two delays (5 or 15 seconds) between stimulus presentation (a black circle occurring in one of eight possible locations) and response (subjects pointed to the location of the target stimulus at the end of the delay). Thirty-two trials of each delay condition were presented. The dependent measure was the number of correctly identified targets at each delay. The test was approximately 20 minutes in duration. Practice trials, which were not included in the total score, consisted of 16 target presentations. For the initial eight practice trials, the target remained on the screen for 5 seconds and overlapped with the eight target choice displays. Because there was no delay between target presentation and response, accurate responding did not require memory, but required the ability to perceive test stimuli and point to the target. The next eight practice trials were identical to the 5-second delay trials and were also administered to ensure that subjects understood test procedures.

Procedure

Clinical and cognitive assessments were performed at baseline and 17 and 29 weeks after initiation of clozapine or risperidone treatment. Clozapine was initiated at 12.5 mg/day and gradually titrated to 500 mg/day by day 28. Risperidone was initiated at 1 mg/day and gradually titrated to 6 mg/day by day 15. Simultaneous with beginning clozapine or risperidone, baseline antipsychotic medication was gradually decreased. Treatment was continued for up to 29 weeks with maximum dosage of 800 mg/day of clozapine or 16 mg/day of risperidone after 5 weeks.

Statistical Analyses

Changes in spatial working memory performance were examined by computing mixed effects regression models

(21) with drug (clozapine or risperidone) as the independent variable, baseline spatial working memory performance as a covariate, and spatial working memory performance at 17 weeks and 29 weeks as the repeated dependent variables. The main effect for drug in these analyses is a test of whether the two medication groups differed in spatial working memory performance after baseline performance was controlled. Analyses were conducted by using SAS PROC MIXED

(22). Parallel analyses were performed for the 5- and 15-second delays of the spatial working memory test. In order to evaluate whether associations between symptoms and cognitive functioning accounted for the observed drug effects, BPRS psychotic symptom and anergia subscale scores at the two assessment points were included as changing covariates in two subsequent mixed effects models with the same independent and dependent variables.

Results

Subjects receiving clozapine and risperidone did not differ in terms of any background characteristic or on measures of baseline psychopathology and spatial working memory, as determined by t tests and chi-square analyses (

Table 1). A total of 64 subjects (65%) completed the 17-week assessment, 46 subjects (47%) completed the 29-week assessment, and 35 subjects (36%) completed all three assessments. Comparisons between study completers and noncompleters on background characteristics, symptoms, and cognitive performance indicated no significant differences (

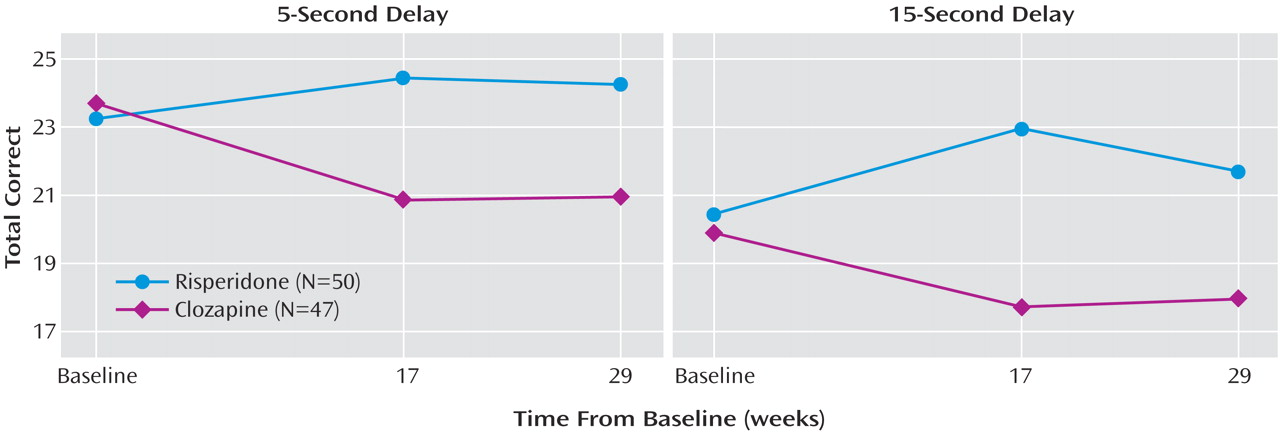

Table 1). Seven subjects with baseline values only were excluded from the analysis. The mixed effects regression models indicated a significant main effect for drug for spatial working memory at the 5-second delay (F=6.60, df=1, 61, p<0.02) and the 15-second delay (F=13.52, df=1, 61, p=0.0005). The addition of the covariates of psychotic symptoms and anergia to the models had negligible effects on the main effect for drug (5-second delay: F=6.76, df=1, 58, p<0.02; 15-second delay: F=13.76, df=1, 58, p=0.0005). None of the drug-by-time interactions was statistically significant (p>0.10). As can be seen in

Figure 1, the main effects for drug reflect a pattern in which the spatial working memory performance of patients receiving risperidone improved from baseline at both the 5- and 15-second delay conditions, whereas the performance of patients receiving clozapine worsened.

Discussion

In this 29-week, double-blind evaluation of the effects of clozapine versus risperidone on spatial working memory, the performance of patients receiving risperidone improved and that of patients receiving clozapine worsened. The differential effects of clozapine and risperidone on spatial working memory performance were evident at 17 weeks of treatment and consistent through 29 weeks. The effects of clozapine and risperidone were similar for both the 5- and the 15-second delay conditions, and were actually stronger when symptoms were statistically controlled.

The differential effect of risperidone and clozapine on spatial working memory performance may be due to differences in the receptor affinities of the two drugs. Specifically, clozapine has substantial anticholinergic properties that risperidone lacks

(17). That the anticholinergic properties of clozapine account for the worse performance on the spatial working memory task is supported by substantial evidence that anticholinergic drugs impair this function

(23) and by evidence that clozapine impaired performance on a visual memory task similar to the spatial working memory task

(11). The improvement in spatial working memory performance associated with risperidone treatment may be due to its ability to enhance dopaminergic turnover in the frontal cortex in the absence of potent anticholinergic effects, consistent with the effects of experimental dopaminergic agonists on spatial working memory performance in nonhuman primates, as stated in the introduction.

The findings in the current study are consistent with those from a previous double-blind comparison of haloperidol and risperidone that used the same spatial working memory paradigm

(8). In that study, haloperidol worsened performance compared with risperidone, an effect associated with benztropine use in patients receiving haloperidol. Risperidone treatment was associated with improved performance relative to haloperidol and to baseline performance, similar to results reported here. Taken together, these two studies support the conclusion that risperidone improves spatial working memory, perhaps by potentiating prefrontal dopaminergic activity.

There was significant attrition in the current study, with 97 subjects participating in the baseline assessment, 62 (64%) at the 17-week assessment, and 35 (36%) at the 29-week assessment. However, there were no differences between patients who dropped out and study completers in terms of any background characteristics, baseline symptoms, or spatial working memory performance. Furthermore, there were no differences in the dropout rate between the clozapine and risperidone groups, suggesting that two drugs were comparably tolerable.

Treatment-related changes in spatial working memory performance were unlikely to be related to differential drug impact on stimuli perception or motor response because practice trials with no delay between stimuli and response were conducted before testing to ensure that subjects were able to 1) perceive test stimuli, which were relatively large (1-inch diameter circles), and 2) carry out the response (pointing to a target stimulus) with 90% accuracy. Risperidone and clozapine may have differential impact on aspects of attention necessary for task performance, a topic of interest for future studies.

In sum, clozapine and risperidone demonstrated differential effects on spatial working memory, with clozapine impairing performance and risperidone improving it. These effects appear to be due mainly to the antimuscarinic blockade produced by clozapine and the enhanced prefrontal dopaminergic transmission associated with risperidone.