It is now recognized that ADHD, once thought to be exclusively a childhood disorder, frequently persists into adulthood, afflicting approximately 4% of the U.S. adult population (

1) and generating significant impairment in academic, occupational, social, and emotional functioning (

2,

3). This impairment may result in completion of fewer years of education and elevated rates of unemployment, antisocial behavior, interpersonal conflict, marital separation, and divorce. Adults with ADHD are also at significantly greater risk for substance use disorders (

4) as well as other comorbid disorders, such as anxiety and depressive disorders (

1).

Adult studies of stimulant (

5) and nonstimulant (

6) medication, paralleling results with children, have found these agents to be effective in reducing the core symptoms of ADHD. However, there are limitations associated with drug treatment. First, little is known about the impact of pharmacotherapy on the functional impairment typically associated with ADHD (

7), particularly in time management and organization. Given the likely underdevelopment of meta-cognitive skills in these areas in youths with ADHD (

8), drug treatment alone may not be sufficient to remediate these deficits, and explicit skills training in adulthood may be necessary. Second, 20%–50% of adults do not respond to drug treatment or have adverse responses (

9), which highlights the need for additional interventions. Furthermore, since response to medication treatment is typically defined as having at least a 30% reduction in symptoms (

9), many patients considered to have responded do not achieve full remission, leaving room for improvement through other modalities. Thus, there is clearly a need for psychosocial interventions to help adults with ADHD develop essential self-management skills.

A recent review (

10) revealed that there has been limited research on psychosocial treatments for adults with ADHD. A case series (

11) and several open studies of group (

12,

13) and individual (

14) cognitive-behavioral treatments yielded promising results. However, controlled studies have been limited to trials of group-administered (

15) and individually administered (

16) cognitive-behavioral interventions, each compared to a waiting list control condition. In both cases, significantly greater improvement in core ADHD symptoms was observed in the treated group. Yet, while these studies yielded large effect sizes in the treated group and controlled for the passage of time, they enrolled small samples (15–22 participants per condition) and did not control for nonspecific effects of treatment (e.g., therapist support), which may exert powerful effects on treatment response (

17,

18).

Over the past decade our group has been developing, studying, and refining meta-cognitive therapy, a group-administered intervention that incorporates cognitive-behavioral principles and was designed to foster the development of executive self-management skills. We chose to focus on time management and organization because difficulties in the attentional domain are more prevalent than those in the hyperactive-impulsive domain among adults with ADHD and are most consistently related to clinician ratings of severity of illness and impairment (

19). Moreover, our clinical experience indicates that problems with impulsivity, social behavior, and mood control are common only to a subset of patients and require a different intervention format. The group format was selected because 1) the skills and strategies to be imparted lend themselves to semistructured presentation; 2) the group format provides opportunities for positive modeling, social reinforcement, and social support; and 3) the group is a cost-effective treatment delivery mode.

Our first study of meta-cognitive therapy (

20) found that adults who completed our manualized group program showed robust change from baseline to posttreatment assessment on standardized self-report measures of ADHD symptoms and executive skills. Given these positive results, we undertook the present study to rigorously examine the efficacy of meta-cognitive therapy by comparing self-report, observer report, and independent evaluator ratings of patients who received meta-cognitive therapy and patients who received supportive therapy. We postulated greater positive change in the meta-cognitive therapy group than in the supportive therapy group. We further hypothesized that patients concurrently receiving medication to treat ADHD would show an enhanced positive response to meta-cognitive therapy because the medication would allow them to focus better, process and retain more during the therapy sessions, and facilitate the practice of strategies between sessions. Finally, we hypothesized that by improving functioning, meta-cognitive therapy would enhance feelings of efficacy and competence, thereby yielding secondary improvements in comorbid symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Method

Design

Eighty-eight adults rigorously diagnosed as having ADHD were stratified by use of ADHD medications (stimulants or atomoxetine) and otherwise randomly assigned to receive either meta-cognitive therapy or supportive therapy; the latter was intended to control for nonspecific therapeutic effects of a group intervention. Response was assessed immediately before and after treatment via a structured interview completed by an independent (blind) evaluator and by questionnaires completed by the patient and a significant other. Each group consisted of six to eight participants. One meta-cognitive therapy and one supportive therapy group intervention were run concurrently in a "cohort" to ensure that the groups were matched on the percentage receiving ADHD medications and were equivalent with respect to environmental changes (e.g., seasonal and holiday periods).

The study was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed written consent to participate.

Participants

Prospective participants were referred from New York area medical and psychiatric clinics, ADHD advocacy and self-help groups, community psychiatrists and primary care physicians, university health services, and postings on clinical trials web sites.

Participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 65 and have a DSM-IV diagnosis of ADHD, predominantly inattentive or combined subtype. Exclusion criteria were active substance abuse or dependence; suicidality; overtly hostile or aggressive behavior likely to alienate group members; "asocial" characteristics (e.g., pervasive developmental disorder); cognitive disability (estimated IQ <80); psychosis; borderline personality disorder; Alzheimer's disease or other dementia; overt neurological disorder; and a childhood history of abuse or trauma or other severe psychiatric condition that confounded ascertainment of childhood ADHD symptoms. Patients with other axis I psychiatric disorders were eligible for participation. Individuals receiving psychotropic medication had to be stabilized on a given drug for at least 2 months and on a given dose for at least 1 month. Patients were instructed to defer nonessential changes in their therapeutic regimen (either medication or psychotherapy) until the end of treatment.

Assessments

Diagnostic assessments

The diagnosis of ADHD was based on the Conners Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID;

21). Also required was a T-score of at least 65 (93rd percentile) on the DSM-IV inattention subscale of the Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scales–Self-Report: Long Version (CAARS-S;

22,

23) and a T-score of 63 (90th percentile) on the inattention/memory subscale. The latter subscale consists largely of items that gauge the severity of the difficulties in time management and organizational functions that constitute the focus of meta-cognitive therapy. The presence of childhood symptoms was confirmed by at least one of the following: self-report of four or more childhood symptoms in one domain (inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive) on the CAADID; report of four or more symptoms in a given domain on the Childhood Symptom Scale–Other Report (

24) by the parent or other adult who knew the patient in childhood; or report of symptoms of ADHD on school report cards or a childhood psychological evaluation. Comorbid conditions were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (

25) and the module for borderline personality disorder from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (

26). IQ was estimated using four subtests of the WAIS-III (vocabulary, similarities, block design, and matrix reasoning), as described by Tellegen and Briggs (

27).

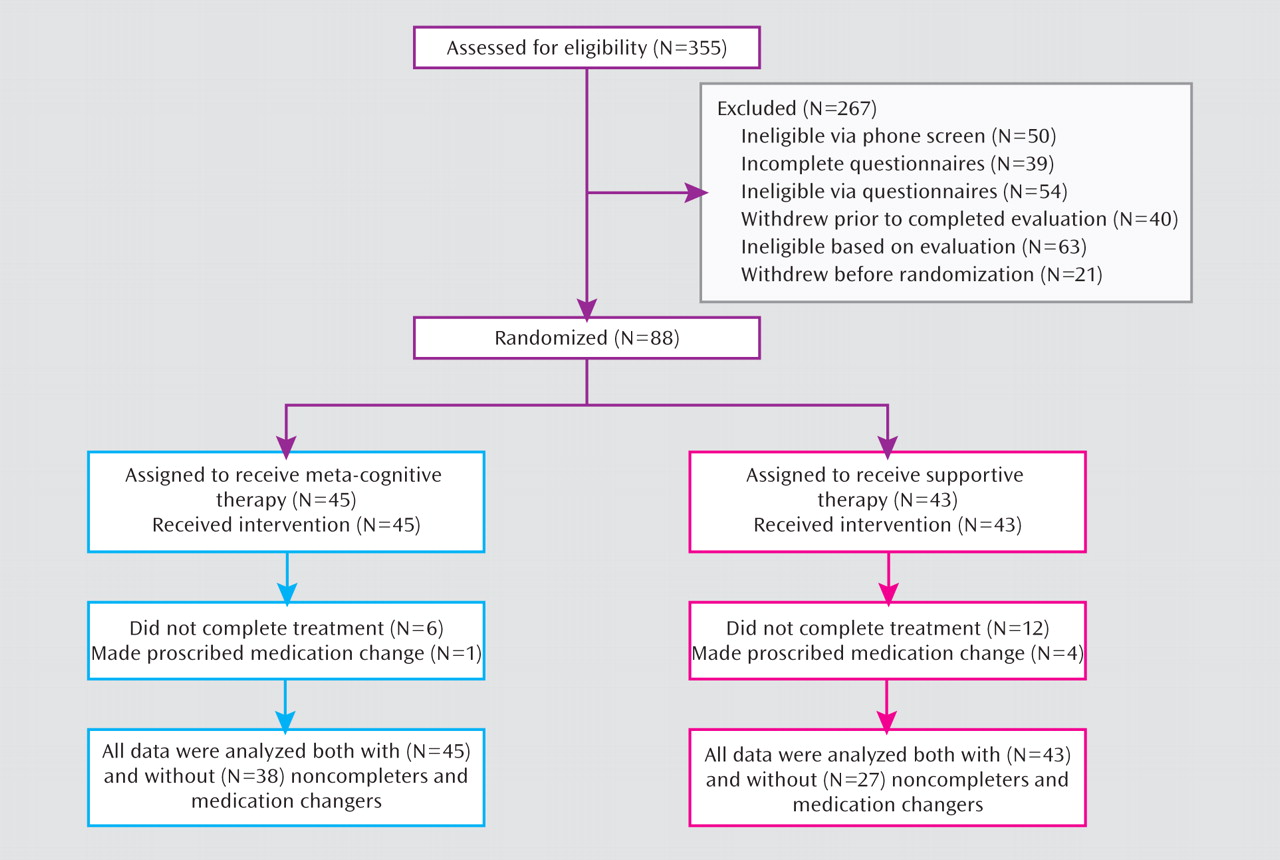

Figure 1 summarizes the flow of participants through each stage of the study.

Assessments of response to treatment

Patients were assessed by the independent evaluator before and after treatment using the Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale (AISRS), a structured interview developed to assess the 18 DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD (

28). Clinician evaluators were licensed psychologists or board-eligible psychiatrists who had been trained on the AISRS to a reliability of 0.90. To reduce rater variance, the same evaluator administered the interview to a given participant before and after treatment. The symptom score (0–3) summed across the nine inattention items served as one of two primary outcome measures for the study. The CAARS-S inattention/memory subscale score served as the other primary outcome measure. In addition, the following self-report questionnaires were completed before and after treatment: the Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scales (

29); the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Adult Version (

30); the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI;

31); the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Inventory (

32); and the On Time Management Organization and Planning scale (possible scores range from –102 to +102), which was developed and previously used in our program to assess those skills (

20). The CAARS–Observer Report: Long Version (CAARS-O) was also completed before and after treatment by a spouse, partner, family member, or close friend of the participant, with the participant's consent. The independent evaluator also administered the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) using a structured instrument (

33).

Meta-Cognitive Therapy

Principles of meta-cognitive therapy

In meta-cognitive therapy, cognitive-behavioral principles are employed to 1) provide contingent self-reward (e.g., for completing an aversive task); 2) dismantle complex tasks into manageable parts; and 3) sustain motivation toward distant goals by visualizing long-term rewards. Traditional cognitive-behavioral methods that challenge anxiolytic and depressogenic cognitions are also incorporated. Support from, modeling of, and reinforcement by other group members and the therapist are important components of the treatment that serve to stimulate, enhance, and maintain positive gains.

Cues to promote generalization and maintenance

The program also makes use of self-instruction using phrases that link a problematic situation (cue) with a cognitive response that provides a solution to that problem. An example is "If I am having trouble getting started (cue), then the first step is too big (solution is to break task down into parts)." Another example, designed to cue individuals to minimize distracters in their organizational space, is "Out of sight, out of mind." Such phrases are repeated strategically throughout the program so that they become part of the individual's problem-solving repertoire, thereby enhancing generalization and maintenance of gains.

Content of meta-cognitive therapy

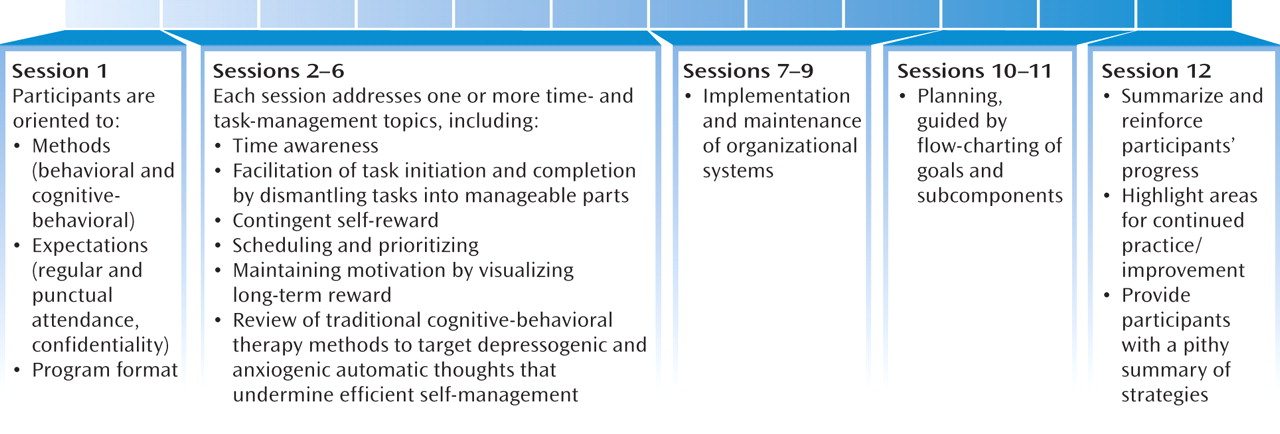

The sequence of treatment sessions, displayed in

Figure 2, is hierarchical in nature, beginning with training in specific skills (e.g., mechanics of planner use) and progressing to higher-order skills that encompass both time management and organization (i.e., planning).

Session format

The first hour of each 2-hour session is devoted to a roundtable review of each participant's experience with the most recent home exercise to ascertain and address cognitive, situational, and emotional obstacles to implementation; suggest additional or alternative strategies; and address counterproductive emotional responses. The second half of each session begins with a presentation of the new topic and corresponding strategies, followed by an in-session exercise to illustrate or model each technique. Sessions conclude with an explanation of the next home exercise and anticipatory troubleshooting.

Supportive Therapy

The supportive therapy condition was designed to control for nonspecific elements of the meta-cognitive therapy program, including session and treatment duration (2 hours per week for 12 weeks), group support and validation, therapist attention, and psychoeducation, but without the didactic strategies and exercises contained in the meta-cognitive therapy program. A manual delineated the techniques and strategies that were prohibited and permitted to the therapist during supportive therapy sessions.

Program structure

Each supportive therapy series commenced with a brief discussion of the program orientation and the role of the therapist as an educator and facilitator. The group was characterized as a mechanism for providing information (e.g., addressing and dispelling myths), uniting around shared experiences, and fostering a network of support.

During the initial session, group members were asked to identify a specific goal to address during the program. Each subsequent session was subdivided into two segments, with the initial half devoted to a review of events that transpired during the preceding week, including challenges or positive accomplishments; the second portion, when time permitted, involved a therapist-led discussion of a specific psychoeducational theme, elicited from group members at the outset of the session. Although the specific topics varied somewhat across groups, the most typical areas covered included primary symptoms of ADHD; everyday manifestations of ADHD symptoms; and psychopharmacological treatment. Throughout the various sessions, each therapist responded by providing psychoeducation, offering support and encouragement (e.g., highlighting positive changes and effort), and/or referring the problem to the group for alternative solutions.

Therapists and Training

Two psychologists who were already highly experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults (D.J.M. and J.W.) were thoroughly trained in meta-cognitive therapy and support interventions and served as therapists. Each therapist led half of the meta-cognitive therapy groups and half of the support groups in randomized sequence.

Fidelity Ratings

Therapist competence and adherence to the treatment protocols were rated on a checklist (available from the authors on request) developed following the recommendations of Waltz et al. (

34). All treatment sessions were taped, and four sessions from each 12-session series were randomly selected to be rated by a therapist experienced in cognitive-behavioral therapy (48 tapes in all). Comparison of ratings revealed no differences between groups in mean ratings of therapist competence and also indicated that there were no instances of contamination of the supportive therapy condition by use of behavioral or cognitive-behavioral interventions.

Data Analyses

The treatment groups were compared on baseline characteristics using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Because the treatments were conducted in groups, we investigated the intracluster correlation due to group, cohort, and group leader in the outcome change (pre- minus posttreatment) measures, controlling for the pretreatment measure. These analyses were conducted using mixed models that specified group, cohort, and group leader as random effects. General linear modeling was used to compare the degree of change in the two treatment groups, controlling for the pretreatment measure. Models that included the interaction of treatment with the pretreatment measure were also run to assess whether any effects of treatment differed by pretreatment symptom severity. Additional models also incorporated interactions of treatment with potential moderators of treatment response, including demographic characteristics, comorbid diagnoses, and medication status.

Results

Sample Characteristics

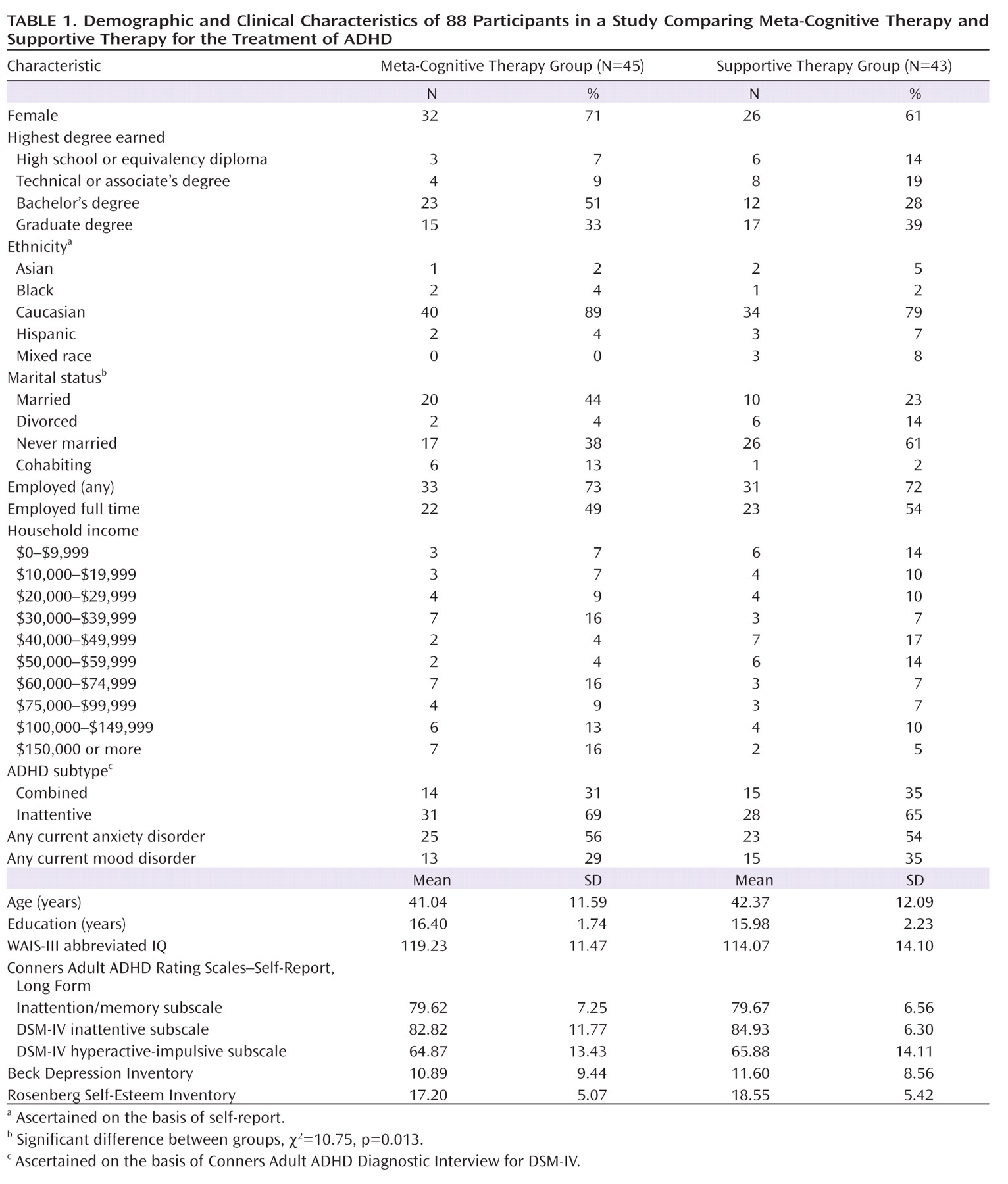

Of 355 individuals screened, 88 who met full eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to treatments; 45 were assigned to meta-cognitive therapy and 43 to supportive therapy. The two treatment groups did not differ on any sociodemographic or clinical variables, with the exception of marital status (

Table 1). Although this was a largely well-educated sample, only half were employed full time, and household income in both groups evenly spanned 10 intervals from ≤$9,999 to ≥$150,000.

Attrition

Five participants in each group dropped out of treatment. Participants considered not to have completed the program additionally included those who missed more than three sessions; missing a session was defined as missing at least half of a session. In this category were one participant in the meta-cognitive therapy group and seven in the supportive therapy group. Five participants made proscribed medication changes during the 12-week program—one in the meta-cognitive therapy group and four in the supportive therapy group. Posttreatment outcome data were obtained from all participants except seven dropouts (four in the meta-cognitive therapy group and three in the support group).

Those who did not complete the program and those who made proscribed medication changes constituted 16% of the meta-cognitive therapy group and 37% of the supportive therapy group (χ2=5.34, df=1, p=0.02). Participants who completed the program (N=65) were more likely than those who did not and those who made medication changes to be female (72% compared with 48%, respectively, χ2=4.53, df=1, p=0.03) and to be of the predominantly inattentive subtype (74% compared with 48%, χ2=5.21, df=1, p=0.02). Those included and those excluded from the analyses did not differ with respect to any other demographic or clinical characteristics.

Analyses of ADHD-Related Measures

The primary outcome measures were the blind structured interview (AISRS) and the CAARS-S inattention/memory subscale score. We examined effects on the full AISRS as well as on a subscale of the AISRS inattention items consisting of five items that most directly reflect the skills of time management, organization, and planning that are targeted by meta-cognitive therapy: failure to complete tasks, disorganization, avoidance of effortful tasks, losing things, and forgetting things. Because of lower return rates for the CAARS-O scale (in part attributable to limited availability of collaterals), effects on the CAARS-S and CAARS-O reports were examined in separate univariate analyses.

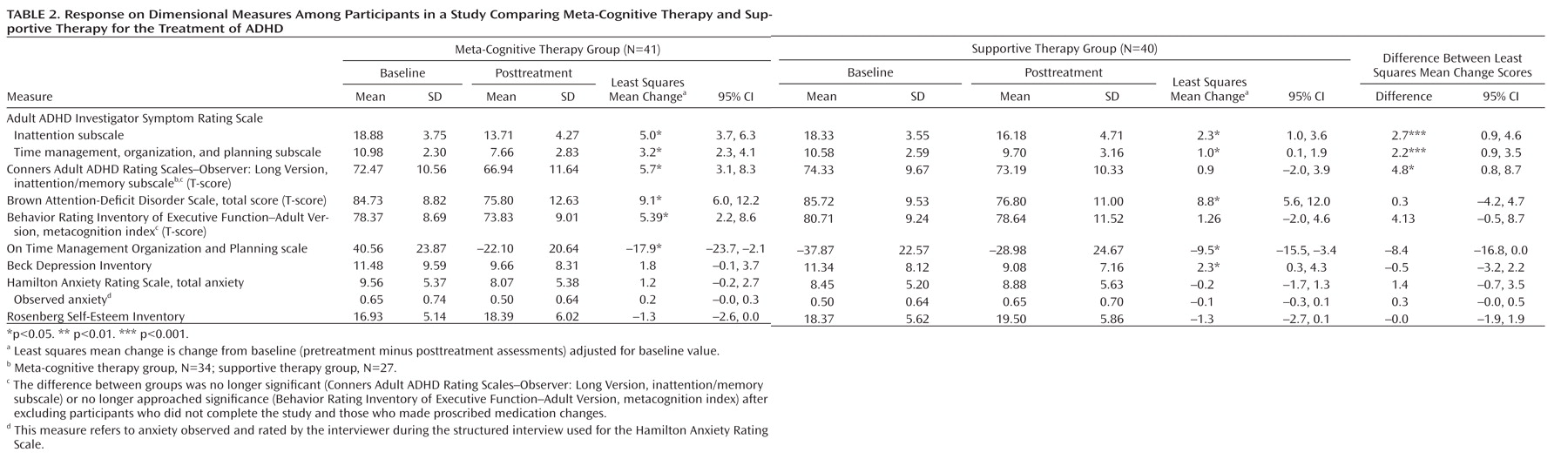

The results of general linear modeling comparing change from baseline between treatment groups, adjusting for the baseline value of the change outcome measure, are summarized in

Table 2, along with the unadjusted pre- and posttreatment mean values and change scores adjusted for baseline by treatment group.

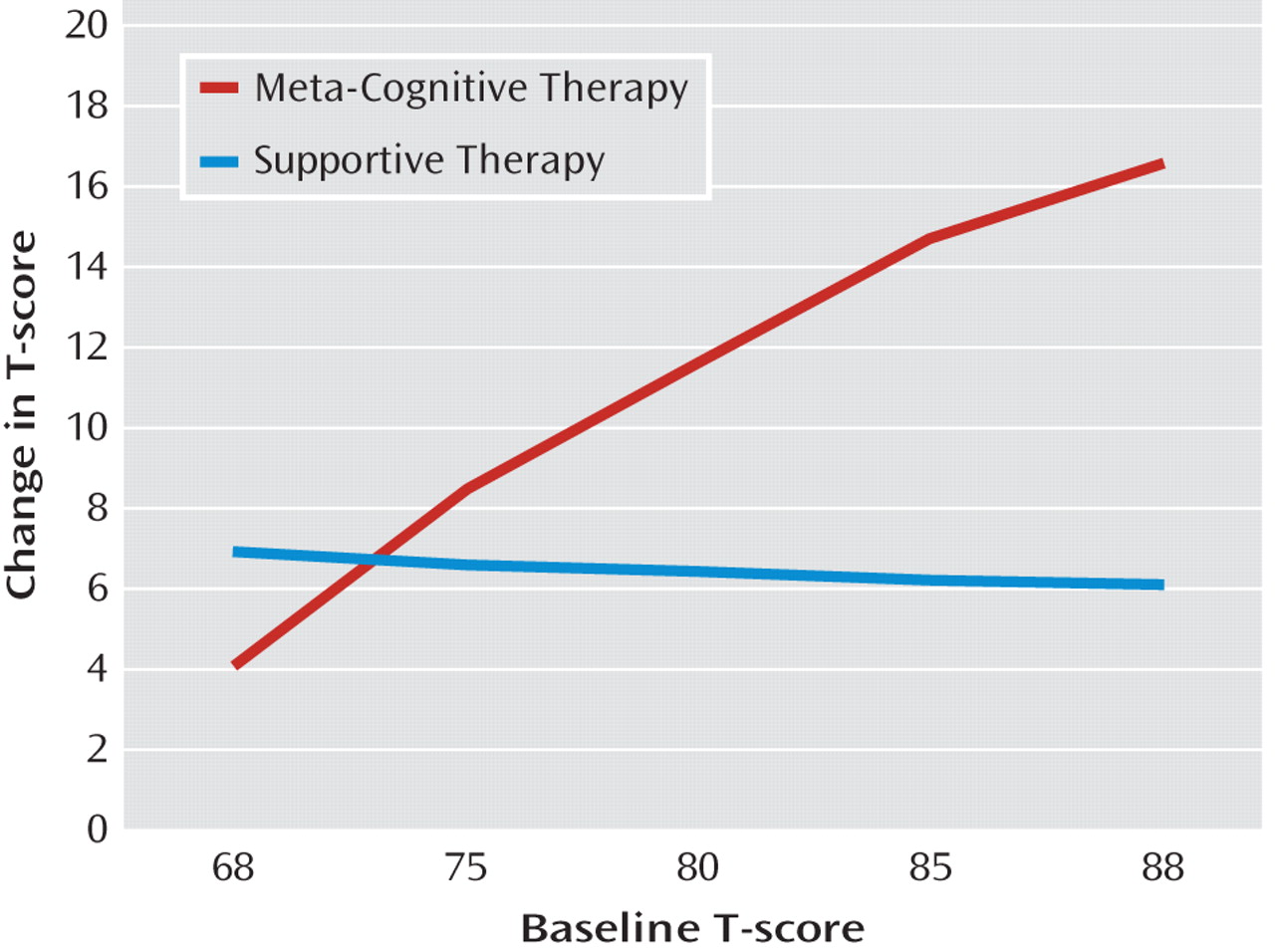

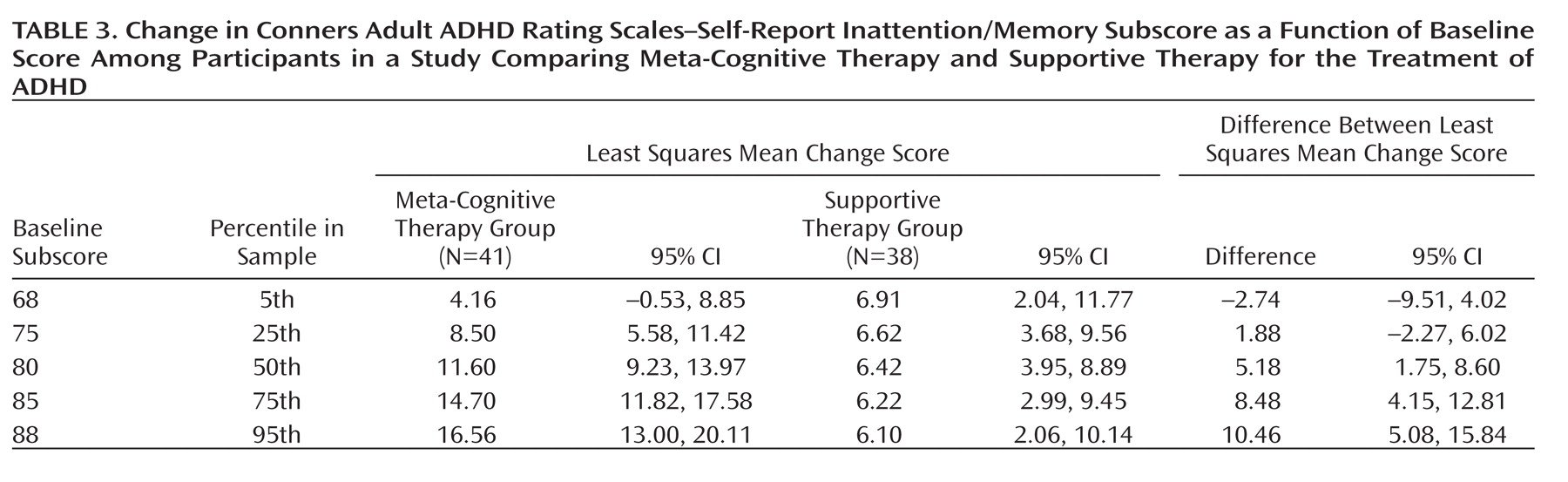

Only one statistically significant interaction between baseline score and response to treatment was observed, and that was on the CAARS-S inattention/memory subscale score. The results of the analysis of change on this variable are thus presented separately in

Table 3 and

Figure 3 since there can be no single contrast between treatment groups given the presence of the interaction. The pattern of treatment contrasts indicated that the larger the score at baseline (that is, the more severe the symptoms), the greater the differential improvement observed with meta-cognitive therapy; this occurred whether the data were analyzed with or without those who did not complete the program and those who made proscribed medication changes (interaction coefficients, 0.66 and 0.72, respectively). Change in the support group, by contrast, was stable across the entire range of baseline CAARS-S inattention/memory subscale scores. Baseline AISRS inattention score did not interact with treatment in the analysis comparing change in AISRS following meta-cognitive therapy versus supportive therapy. With respect to the change in AISRS inattention score from pre- to posttreatment assessment, controlling for baseline score, Table 2 indicates that the meta-cognitive therapy group improved by 5.0 points, whereas the supportive therapy group improved by 2.3 points, a difference between groups of 2.7 (95% CI=0.9–4.6, p<0.005) or 56% of the overall standard deviation of the change score (SD=4.8). The same pattern (i.e., greater change in meta-cognitive therapy versus support) was evident on the AISRS time management, organization, and planning subscale and the CAARS-O inattention subscale. On all of the foregoing measures, examination of confidence limits revealed significant change from pre- to posttreatment assessment for supportive therapy as well as for meta-cognitive therapy. On the Brown scales and the On Time Management Organization and Planning scale, there was significant change from pre- to posttreatment assessments for supportive therapy as well as for meta-cognitive therapy. However, the change score difference between groups was either not significant (Brown scales) or only marginally significant (On Time Management Organization and Planning scale). The metacognition index of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Adult Version yielded marginally significantly greater improvement in meta-cognitive therapy compared to supportive therapy; change in meta-cognitive therapy but not supportive therapy was significant.

Analyses of Measures of Comorbidity

No differences were observed between treatment groups in pre- to posttreatment assessment change scores for depression (BDI), self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Inventory), or anxiety (HAM-A). With the exception of a small but significant improvement on the BDI in the supportive therapy condition, examination of confidence intervals for change scores for each treatment group separately showed no significant effects for any of these outcome variables. Given that the sample as a whole scored within normal limits on the BDI, we reexamined the data to ascertain whether there was a significant decrease in BDI score for those individuals who had a concurrent axis I mood disorder. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that for these participants mean BDI scores decreased from 17 to 13, yielding a significant main effect of time (pre- to posttreatment assessment; F=4.99, df=1, 24, p=0.035) but no interaction with treatment condition. A similar analysis with HAM-A score for those who had a concurrent anxiety disorder produced no significant results.

Intracluster Correlation

Mixed-model ANOVAs were conducted to adjust for intracluster correlation using group, therapist, and cohort as clusters. Therapist consistently did not account for any intracluster correlation. Adjusting for group and cohort simultaneously as random variables did not affect the significance of the treatment effects noted in Table 2.

Responder Analyses

The data were also examined to determine whether participants exhibited clinically meaningful change in response to treatment. On the blind structured interview of DSM-IV inattention symptoms (AISRS inattention items), a positive response was defined as a decrease of at least 30% (maximum score=27), consistent with the criterion used in pharmaceutical trials (

9). A positive response on the CAARS-S inattention/memory subscale score was defined as a decrease of at least 10 T-score points (one standard deviation). Seven participants who dropped out and for whom posttreatment data were not available were conservatively scored as nonresponders on these variables.

On the AISRS inattention items, 19 participants (42.2%) in the meta-cognitive therapy group met the response criterion, compared to only five (12%) in the supportive therapy group (χ2=10.38, df=1, p=0.002). On the CAARS-S inattention/memory subscale, 24 (53%) participants in the meta-cognitive therapy group and 12 (28%) in the supportive therapy group met the response criterion (χ2=5.88, df=1, p=0.018). Logistic regression, with AISRS inattention score response status as the dependent variable, was performed to control for baseline AISRS inattention score. Results revealed a significant effect of treatment group on response status (odds ratio=5.41; 95% CI=1.77–16.55) favoring meta-cognitive therapy.

Analyses of Participants Who Completed the Program

The above analyses were repeated excluding all those who did not complete the program or who made proscribed medication changes. The pattern of significance across dependent measures was identical to that of the entire sample except that the effect of treatment was no longer significant for the CAARS-O inattention subscale, a result most likely due to the reduction in sample size.

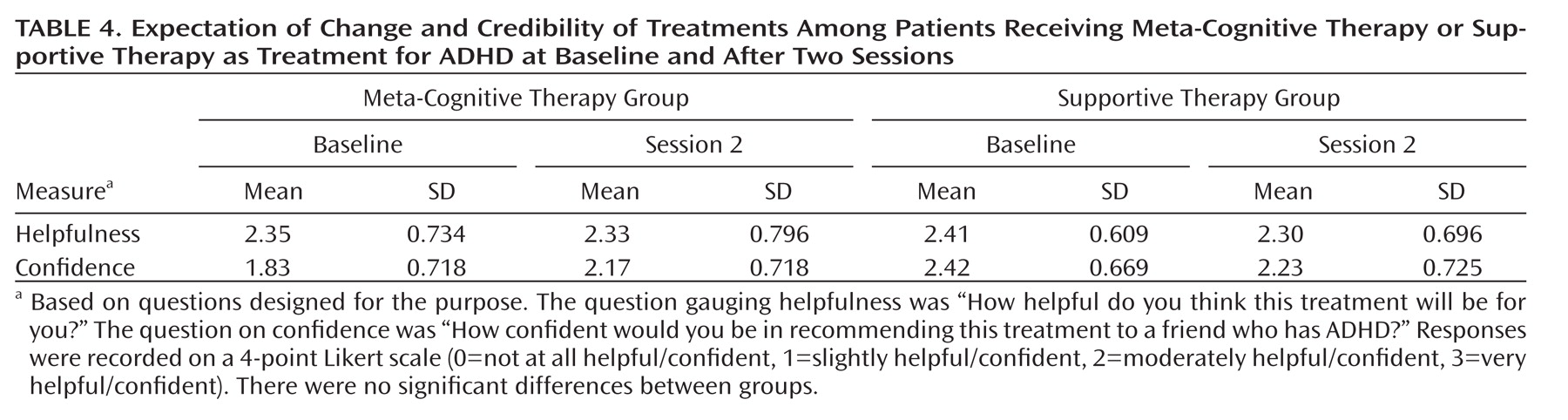

Expectation of Change and Credibility of Treatments

Expectation of change and treatment credibility were assessed using two questions (coded on a 4-point Likert scale) derived from Borkovec and Nau (

35) concerning the anticipated helpfulness of treatment and confidence in recommending the treatment to another. Group responses were compared before the start of treatment and again at the end of session 2, after participants had been exposed to the treatment group methods but before any actual change due to treatment might have confounded measurement of expectancy. The results (

Table 4) indicated no significant difference between groups at baseline, nor significant change in either group after exposure to two treatment sessions.

Moderators of Response

The following covariates were added one by one to the general linear model to examine whether these potential moderators attenuated or interacted with the effects of treatment: age, gender, ethnicity, education, household income, marital status, employment status, IQ, ADHD subtype, ADHD medication, and comorbid depressive and/or anxiety disorder. In each analysis the effect of meta-cognitive therapy compared with supportive therapy remained significant while controlling for the covariate, and in no case did the covariate interact significantly with the treatment effect.

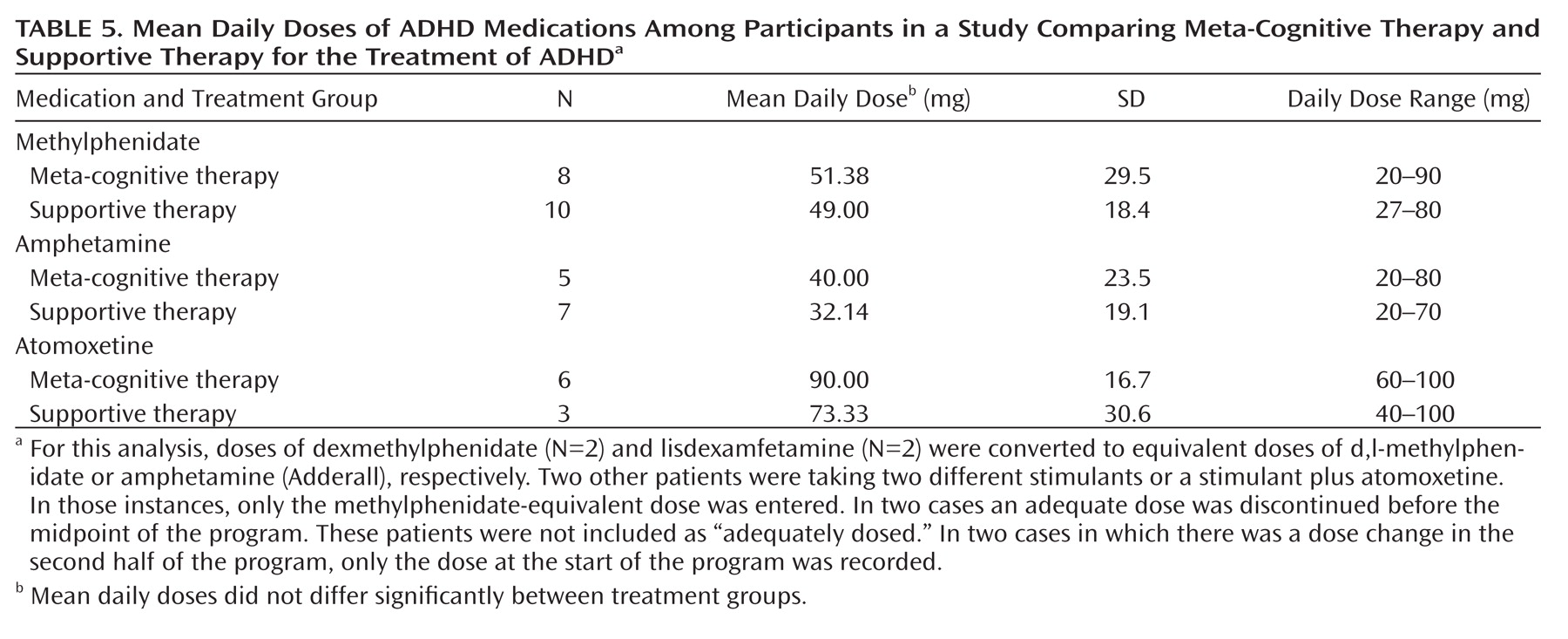

Of the 88 participants, 49 (56%) were receiving FDA-approved medication for ADHD. Of these, 36 patients (18 in each treatment group) were receiving a minimally adequate dose, defined as 20 mg/day of methylphenidate, 20 mg/day of amphetamine, or 40 mg/day of atomoxetine, as determined on the basis of the most recent dose-response studies in adults (

36–

38). The treatment groups did not differ significantly in the type, adequacy, or dose of medication treatment (

Table 5). Unexpectedly, adequately medicated patients did not differ from other patients on any measure of baseline severity of ADHD symptoms. Chi-square analysis revealed no difference between these subsets of patients in response rate to treatments, as defined either on blind structured interview (AISRS) or by CAARS-S (p>0.05); effect sizes (eta) were 0.033 and 0.053, respectively. Similarly, ANOVA of dimensional scores on the CAARS-S inattention/memory subscale showed no impact of medication on response; the effect size (partial eta-squared) corresponding to the three-way interaction among medication, time (pre- to posttreatment assessment), and treatment group was <0.001. The effect size corresponding to the medication-by-time interaction (collapsed across treatments) was 0.002. For participants who completed the study (31 adequately medicated and 39 unmedicated or inadequately medicated patients), effect sizes were similar to those for the full sample.

Mediators of Response

Session attendance and completion of the home exercises in the meta-cognitive therapy group were examined as potential mediators of change in AISRS inattention score. Regression analysis indicated that attendance was not related to response and did not mediate the treatment effect. However, within the meta-cognitive therapy group, completion of the home exercises was significantly related to change in AISRS inattention score (F=6.49, df=1, 38, p=0.015), with a score increase of 0.85 from baseline for each home exercise completed.

Discussion

This study was designed to assess the efficacy of meta-cognitive therapy, a cognitive-behavioral intervention, for the treatment of adult ADHD. Participants randomly assigned to receive meta-cognitive therapy showed greater improvement on standardized measures of inattention symptoms, whether self-rated, observer-rated, or rated by a blind evaluator, than did those in a supportive therapy condition. The finding on the AISRS structured interview favoring a clinically significant response for meta-cognitive therapy over supportive therapy (odds ratio=5.41) provides strong support for the efficacy of this intervention. The fact that groups were initially found to be equivalent in expectation of change suggests that positive expectancy cannot fully account for change. Furthermore, the finding that completion of the home exercise was significantly related to treatment response provides evidence that change was mediated by the active meta-cognitive therapy treatment components. The same may be said of the finding that baseline symptom severity was related to the outcome of meta-cognitive therapy, whereas change in the supportive therapy condition was constant across all levels of symptom severity. The significantly higher total rate of noncompletion and medication change in supportive therapy compared to meta-cognitive therapy may be an indication that patients felt they were deriving less benefit from this intervention.

Although the magnitude of change on the primary outcome measures strongly favored meta-cognitive therapy, patients in the supportive therapy group also reported improvement. It may be that the support in the group reduced demoralization and improved hopefulness, which in turn motivated participants to tackle their own difficulties or discover solutions through reading, talking to others, or trial and error.

The lack of significant change on measures of comorbidity (BDI, HAM-A, and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Inventory) in meta-cognitive therapy may have been due to floor effects on these measures, as scores at baseline were, on average, not in the clinically significant range. Support for this possibility was generated by a post hoc analysis of BDI scores for patients with a concurrent mood disorder, which revealed a significant decrease from pre- to posttreatment assessment for the combined sample, but no differential effect of group assignment. A parallel result was not obtained on the HAM-A for those with concurrent anxiety disorders.

The failure of medication to act as a treatment moderator may be due to several possible factors. First, we had not expected that patients receiving adequate medication would not differ in baseline symptom severity from those not receiving medication. Given that participants were required to meet entry criteria for minimum levels of severity of symptoms, we may have been effectively selecting those who were nonresponders or suboptimal responders to medication. Additionally, although we conducted moderator analyses on a subset of medicated participants who appeared to be receiving minimally adequate amounts of medication, doses for these individuals may not have been adequately titrated and may have been suboptimal. A final possibility is that the program is sufficiently structured and effective that patients are able to benefit whether or not they are receiving effective medication. A more rigorous examination of the effects of medication and meta-cognitive therapy, separately and together, would require a 2×2 design in which medication treatment is optimally titrated for each individual.

Although other demographic and clinical variables did not have significant effects on outcome, larger samples with greater statistical power may be needed to fully ascertain the effects of these potential moderating and mediating variables. In particular, although IQ was not a moderator of response, the mean IQ in this sample was above average. A sample with a greater IQ range would be needed to fully assess the potential moderating effect of this variable and to gauge the generalizability of these treatment results to adults across a broader IQ range.

Overall, the results of this study indicate that meta-cognitive therapy provides significant benefit to patients with ADHD with respect to inattention symptoms that reflect the specific functions of time management, organization, and planning. It is the first published study to formally demonstrate the efficacy of a psychosocial treatment in adults with ADHD compared to a condition that controlled for the nonspecific effects of therapy. It thereby represents a noteworthy contribution to a developing literature supporting the benefits of cognitive-behavioral treatment—whether delivered in group or individual format—for the treatment of ADHD in adults. It will be important in future studies to examine the maintenance of these benefits beyond the termination of treatment and to determine the relative efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial treatments, separately and together, for the treatment of ADHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the expert consultation in research in cognitive-behavioral therapy provided by Jacqueline Gollan, Ph.D., and Richard Heimberg, Ph.D. They also acknowledge the contributions of Megan Wilens, M.D., and Heather Goodman, Ph.D., who served as blind evaluators, and the assistance of Lauren Knickerbocker, M.A., with manuscript preparation.