Borderline personality disorder is associated with high rates of comorbidity. Individuals with borderline personality disorder meet criteria for an average of 3.4 to 4.2 lifetime axis I disorders (

1,

2), including a high prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with estimates as high as 56% (

1,

3,

4). However, little research has focused on the impact of PTSD on the clinical presentation, functioning, and behavioral patterns of individuals with borderline personality disorder, and no studies have examined these issues within the subgroup of suicidal borderline personality disorder patients.

Previous research suggests that those with both borderline personality disorder and PTSD tend to be more impaired overall. Several studies have indicated that the addition of PTSD does not significantly alter the severity of borderline personality disorder (

5,

6), the number of axis II disorders (

6), social adjustment (

6–8), general health status (

7), the frequency of suicide attempts (

5,

8), or hostility (

7,

8). However, the addition of PTSD to borderline personality disorder is associated with higher rates of other axis I disorders, particularly anxiety disorders and major depression (

7,

8), an increased risk of nonsuicidal self-injury (

8), more frequent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (

6), poorer physical health (

7), more impaired global functioning (

6), and a higher rate of childhood sexual and physical abuse (

6). Moreover, the presence of PTSD has been found to decrease the likelihood of attaining remission from borderline personality disorder over a 10-year period (

9).

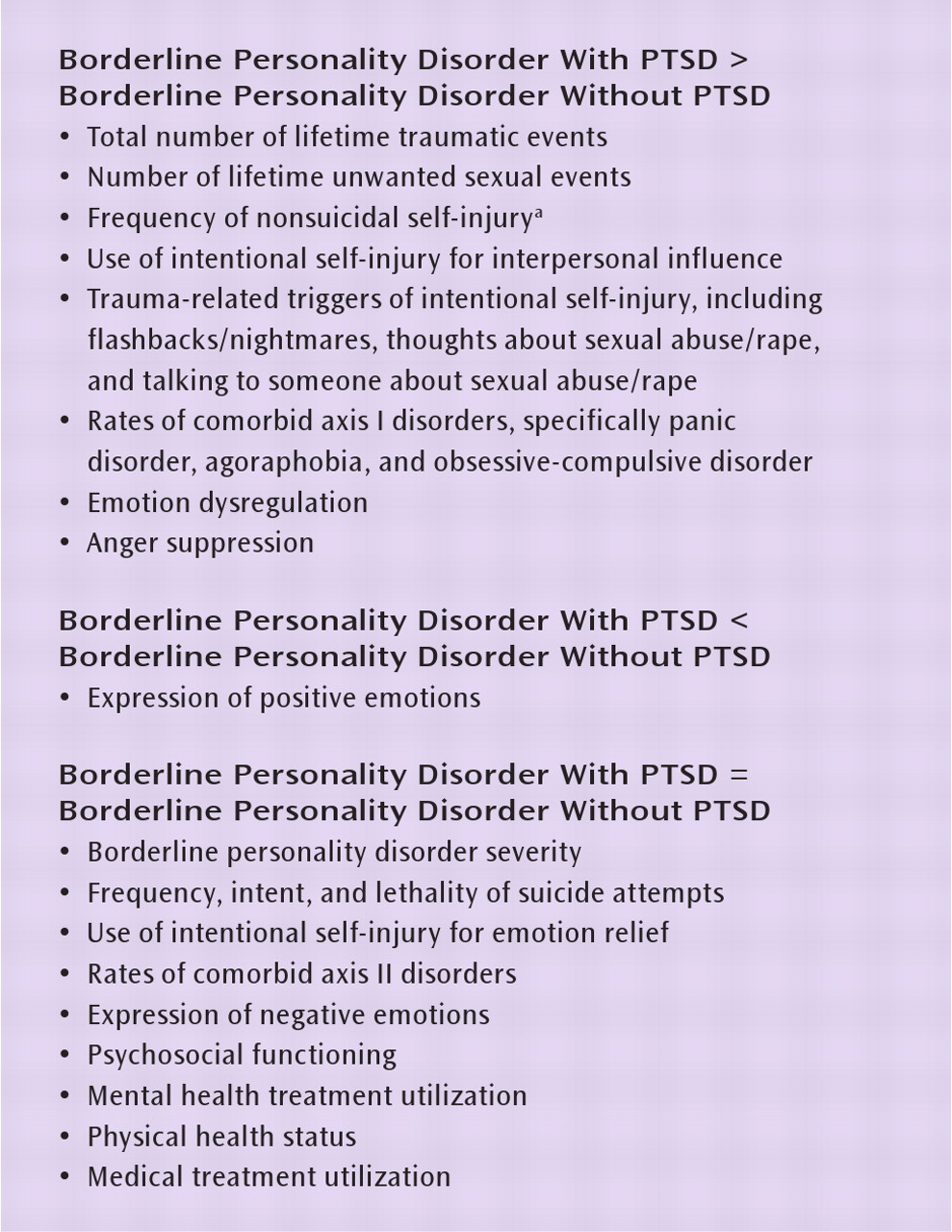

In this study, we sought to replicate and extend previous work by examining the similarities and differences between the clinical presentations of suicidal borderline personality disorder outpatients with and without PTSD. Nine groups of variables were investigated, including borderline personality disorder severity, trauma history characteristics, suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury, comorbid axis I disorders, comorbid axis II disorders, emotion regulation and expressivity, psychosocial functioning, mental health treatment utilization, and physical health status and medical treatment utilization. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that with the exception of borderline personality disorder severity and comorbid axis II disorders, borderline personality disorder patients with PTSD would have greater impairment across each of these domains compared to those without PTSD.

Discussion

This study adds to a growing body of evidence indicating that individuals with borderline personality disorder and co-occurring PTSD are likely to have more complex clinical presentations than those without PTSD. In patients with both disorders, scores for suicide intent and lethality were lower when averaged across both suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury episodes. This is likely accounted for by the trend-level finding indicating that patients with both disorders engaged in more frequent nonsuicidal self-injury. When comparing suicide intent and lethality for suicide attempts only, there was no difference between the two groups. This is in contrast to a previous study (

14) finding that women with borderline personality disorder who had a history of childhood sexual abuse reported more lethal self-injurious behavior than those without such a history, suggesting that it may be childhood sexual abuse, not PTSD, that is predictive of more lethal self-injurious behavior in this population.

Borderline personality disorder patients with and without PTSD also differed in the function and triggers of intentional self-injury. Those with PTSD were more likely to report engaging in intentional self-injury as a way to influence others. They were also more likely to endorse a variety of trauma-related triggers for their episodes of intentional self-injury, including flashbacks, thoughts about sexual trauma, and talking to someone about sexual trauma. It is possible that women with both disorders engage in higher rates of nonsuicidal self-injury because they have a greater number of potential triggers for these behaviors as well as a heightened reactivity to these trauma-related cues. This may suggest that for some individuals with these co-occurring disorders, addressing PTSD criterion behaviors (e.g., trauma cue reactivity) may be necessary in order for functionally related suicidal and self-injurious behavior to decrease. Short-term solutions, such as distress tolerance skills to tolerate difficult emotions and substituting alternative, nonharmful behaviors to manage triggers in more adaptive ways, may be useful in this area (

24). However, the long-term solution for this problem will likely require the resolution of PTSD through more targeted treatments.

Patients with PTSD scored significantly higher on measures of emotion dysregulation and anger suppression and lower on expression of positive emotions. Difficulty expressing positive emotions is consistent with the PTSD diagnostic criterion of restricted range of affect, which typically involves an inability to experience loving and intimate feelings. In addition, theories of PTSD emphasize the extremes in emotional responding that are characteristic of this disorder, including an intrusion phase of intense emotional experiencing (e.g., flashbacks, distressing memories of the trauma) that may trigger emotional numbing (

25). This vacillation between overwhelming emotions and emotional numbing that is common in PTSD may exacerbate the emotion dysregulation that is a core feature of borderline personality disorder. Moreover, this increased emotion dysregulation may contribute to the higher rate of nonsuicidal self-injury among borderline personality disorder patients with PTSD given that nonsuicidal self-injury most often functions to alleviate negative affect (

26).

Patients with both borderline personality disorder and PTSD were more impaired in terms of axis I comorbidity. They were more likely to meet criteria for panic disorder (53% compared with 22%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (21% compared with 0%), and agoraphobia without panic disorder (9% compared with 0%). This is consistent with previous research demonstrating that PTSD has the highest and most diverse rate of comorbid disorders (

27) as well as data from the National Comorbidity Survey indicating that women with PTSD are at particularly high risk for developing co-occurring panic disorder (

28). However, in contrast to findings of previous research (

29), we did not find that PTSD was associated with a higher prevalence of any mood, substance use, or eating disorder. This discrepancy is likely due to the generally high rate of axis I comorbidity found in individuals with borderline personality disorder (

2,

30), as in our sample—in which, for example, high rates of co-occurring major depressive disorder (63%–77%) and substance use disorders (34%–42%) were observed. Taken together, these findings suggest that among women with borderline personality disorder who already exhibit high rates of axis I comorbidity, PTSD further increases the risk of other specific anxiety disorders.

Women with borderline personality disorder who had PTSD reported significantly more total traumatic events as well as nearly twice as many past unwanted sexual experiences (e.g., childhood sexual abuse, adult rape, sexual harassment) as their counterparts without PTSD (16.6 compared with 9.4), a finding consistent with previous research (

6). Women with or without PTSD reported a high total incidence of trauma exposure, averaging 26 to 36 lifetime traumatic events. It will be important to determine the factors that protect some individuals with borderline personality disorder from developing PTSD despite such high rates of trauma exposure.

As hypothesized, no differences were found between the groups on borderline personality disorder severity or the presence of other axis II disorders. These findings are consistent with previous research that has not found borderline personality disorder patients with and without PTSD to differ in terms of the number of borderline personality disorder criteria met (

5,

6) or the number of co-occurring axis II disorders (

6). Our findings extend this previous research to indicate also that the two groups exhibit comparable rates of each specific axis II disorder.

Contrary to our hypotheses, borderline personality disorder patients with and without PTSD also did not differ in terms of overall psychosocial functioning, mental health treatment utilization, or physical health and medical treatment utilization. The findings related to psychosocial functioning differ from previous research that has found higher levels of psychosocial impairment in borderline personality disorder patients with PTSD than in those without PTSD (

6). This discrepancy is likely due to the use of a suicidal sample, as the presence of a recent suicide attempt significantly lowers indices of functioning and may have led to a floor effect. The lack of between-group differences in treatment utilization is also discrepant with previous research (

6,

7) and may be due to a number of factors. First, the sample used for this study was treatment-seeking and thus was self-selecting based on this variable. Second, given previous research that has indicated high rates of treatment utilization in borderline personality disorder compared to other disorders (

31), it is also possible that a ceiling effect exists. For example, the majority of participants in our sample had gone to an emergency department for psychological reasons and had at least one psychiatric hospitalization in the past year. Finally, it is possible that the addition of PTSD to borderline personality disorder does not account for an increase in treatment-seeking behavior.

This study has important limitations. Because our sample included only female patients, only treatment-seeking patients, and only patients with recent and chronic suicidal and/or nonsuicidal self-injury and excluded patients with bipolar or psychotic disorders, our results may not be representative of individuals with borderline personality disorder and PTSD more broadly.

Our results have both theoretical and clinical implications. This study provides additional empirical support for the current diagnostic system, which considers borderline personality disorder and PTSD to be separate, although often co-occurring, disorders. Some researchers have suggested that borderline personality disorder is better described as a trauma-related condition known as “complex PTSD” (

32,

33). However, conceptualizing borderline personality disorder and PTSD as the same disorder would disregard the important distinctions that exist between these two groups. Clinically, given that patients with both disorders appear to have a particularly severe and complex overall presentation, treatments for this population must be able to address these unique features (

34). Results from two previous studies suggest that the addition of a high level of borderline personality disorder characteristics, although related to greater overall impairment, did not prevent individuals from making significant gains with cognitive-behavioral treatments for PTSD (

35,

36). However, these studies excluded suicidal and/or self-injuring patients and did not assess for the full borderline personality disorder diagnosis. In addition, no research has yet examined whether the presence of PTSD significantly alters the course or outcome of treatments for borderline personality disorder. Thus, it will be important for future research to determine whether individuals with co-occurring borderline personality disorder and PTSD fare worse in treatments for either disorder, particularly among those who are suicidal or self-injuring.