Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan parasite. Humans are infected mainly by consumption of undercooked meat containing

T. gondii cysts, by ingestion of oocysts from the feces of infected cats (e.g., through contact with a contaminated litter box, ingestion of unwashed vegetables), or by congenital infection if the mother has a primary infection during pregnancy and passes the infection to the fetus (

1). After infection, rapidly dividing intracellular

T. gondii tachyzoites are disseminated throughout the body. The tachyzoites eventually transform to slowly dividing bradyzoites in tissue cysts, most commonly in brain and muscle. These cysts may remain throughout the life of the host, and unlike tachyzoites, they fail to provoke an inflammatory response. Reactivation of the infection may occur if the host becomes immunosuppressed (

2,

3).

The first studies of an association between

T. gondii and psychosis were published during the period 1953–1957. Since then, many studies have compared

T. gondii status in individuals with schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. Yolken et al. (

4–

6) have provided an overview of previous research and discussion of possible mechanisms by which

T. gondii could cause schizophrenia. In a meta-analysis using schizophrenia cases and controls from 23 studies, Torrey et al. (

7) reported that the odds ratio for schizophrenia associated with

T. gondii was 2.73 (95% confidence interval [CI]=2.10–3.60) and that the odds ratio based on the seven studies with first-episode schizophrenia was 2.54. Subsequent studies also found an association between

T. gondii infection and schizophrenia (

8–

12). One study found significantly more individuals with high-titer

T. gondii response in the schizophrenia group compared with the healthy comparison group and no significant difference for low-titer positive response (

13). A limitation of these various studies is that antibody levels for individuals with schizophrenia were measured at the time of diagnosis, yet psychiatric symptoms are often present sometime before the first diagnosis of schizophrenia. It is unknown whether such incipient psychiatric illness causes behavioral changes that increase the risk of infection with

T. gondii, which then might explain the observed association between

T. gondii and schizophrenia. To avoid this problem, there is a need for prospective cohort studies assessing

T. gondii in adults prior to onset of psychiatric illness. Only one previous study, among U.S. military personnel, was based on measurements of immunoglobulin G (IgG) level in adults before as well as after diagnosis of schizophrenia (

14); in that study, researchers found an association between increasing IgG levels and schizophrenia.

Discussion

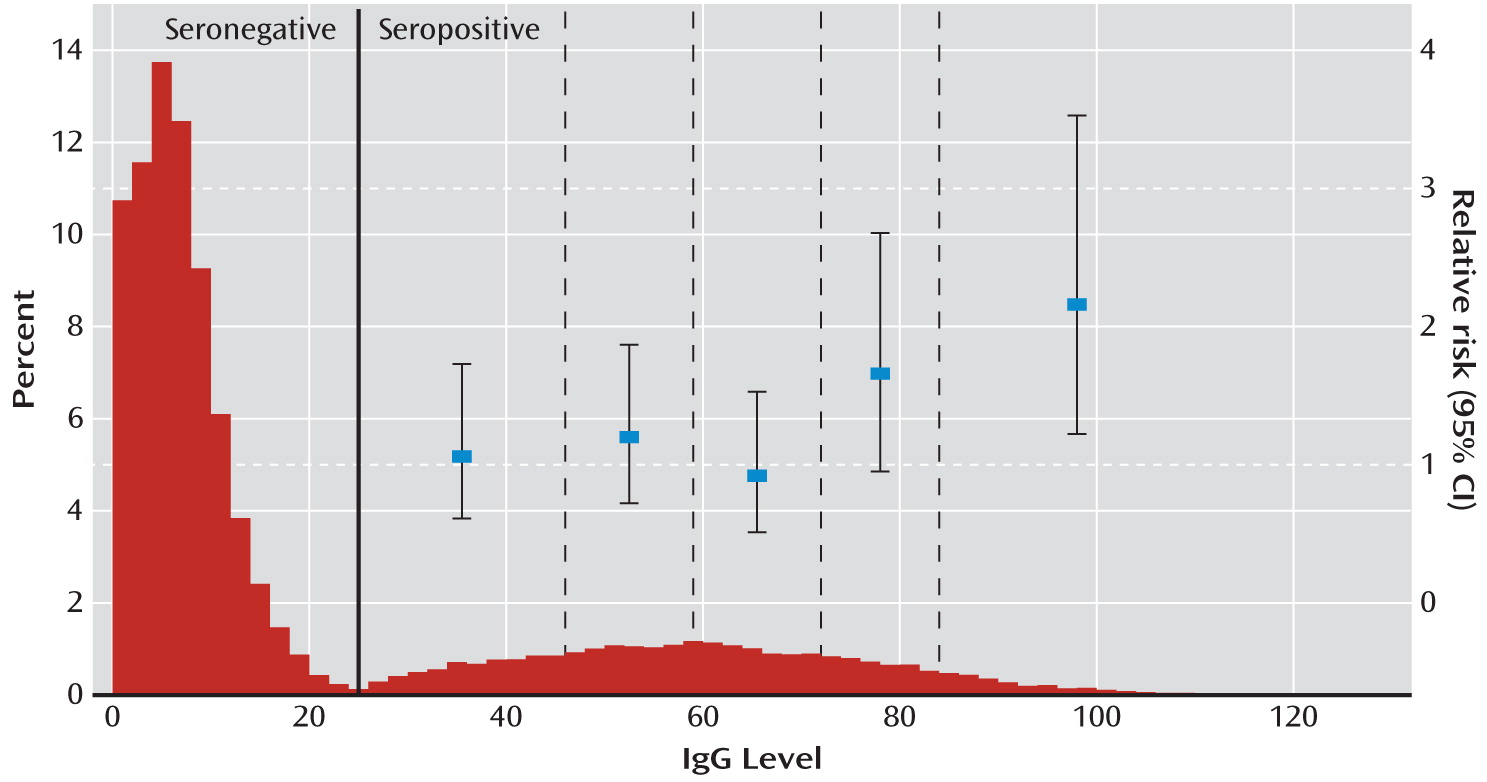

In a prospective follow-up study of women screened for T. gondii at the time of giving birth, we found a significantly elevated risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders associated with T. gondii infection. The greater risk was not explained by psychiatric family history, degree of urbanization at place of residence, or age at delivery. When IgG antibody level was analyzed as a categorical variable, only the highest levels had a significant effect.

Because we had information on infection status at time of delivery only, mothers who became infected with

T. gondii after delivery were considered seronegative in our analyses, which implies that the effect sizes we report are likely to be conservative. Only one previous study assessed

T. gondii antibody levels in adults before as well as after onset of schizophrenia—a nested case-control study by Niebuhr et al. (

14) with 15 exposed cases among military personnel. Even though the Niebuhr et al. study contained 83% men and the present study included only women, the size of the association in the two studies was similar.

To potentially interpret observed associations as causal associations,

T. gondii antibodies had to be measured prior to the onset of psychiatric symptoms (

20). An earlier study of first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Denmark (

22) showed that the duration of untreated psychosis among women was 2 years on average. In a subanalysis, we started follow-up 2 years after delivery, thereby excluding cases with first diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder within 2 years after assessment for

T. gondii antibodies. Given that the size of the association between

T. gondii and schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders was unchanged, it is unlikely that the association found was due to reverse causality (onset of psychiatric symptoms before onset of

T. gondii infection). Our results were virtually unchanged after adjustment for some important confounders, including family history of mental disorders and degree of urbanization of place of residence at the time of delivery. Although this does not exclude confounding from genetic and environmental risk factors for schizophrenia and related disorders, it does lend further credibility to our results.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of

T. gondii and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. We studied a population-based cohort consisting of women across a large area of Denmark, accounting for about one-third of all deliveries in Denmark between 1992 and 1995, with almost complete follow-up data for up to 16 years. Women were included in the study irrespective of social status, and information on

T. gondii IgG level was collected prospectively and independently of the present study. A weakness of the study is that the study population was not a random sample of women giving birth in Denmark. Individuals included in the study population were originally recruited for a study of the maternofetal transmission rate of

T. gondii infection (

15). Pregnant women from five counties in Denmark were offered screening at delivery for primary

T. gondii infection during pregnancy from 1992 to 1996. A first-trimester serum sample from the mother was available for 90.7% of women otherwise eligible for the study. Only 0.18% of eligible women declined to take part in the study. All phenylketonuria cards with blood drawn 5–10 days postpartum from infants of consenting mothers were analyzed for

Toxoplasma-specific IgG. When the test result was positive, the mother's first-trimester sample was thawed and analyzed for

Toxoplasma-specific IgG, to trace seroconversion (

15). For the present study, we were able to retrieve results of IgG measurements for children born only up until January 15, 2005. Apart from this, the only selections made were to restrict the analyses to mothers born in Denmark, to include each mother only once (her first delivery during the study period), and to exclude mothers who had a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder before delivery. We compared the influence of age at delivery, parental history of mental illness, and degree of urbanization of place of residence at the time of delivery on the risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the 45,609 mothers included in the study compared with the 151,950 women who gave birth in Denmark during the study period. We found similar magnitudes and directions for all associations, and thus there was no sign of selection bias with respect to the included confounders. A limitation of the generalizability of the study is the exclusion of nulliparous women, who may have different risk factors for developing schizophrenia. The age distribution of women included in the study was relatively broad, although the largest age group was the 25- to 29-year-olds. Another obvious limitation on the generalizability of the study is that only women were included, although the association between

T. gondii and schizophrenia was similar to that reported by Niebuhr et al. (

14) in their predominantly male military sample.

As noted earlier, because information on the IgG level in the mothers' first-trimester serum samples was available for only a subset of the cohort, we based our analyses on IgG levels in the newborns. Although IgG levels in the child can be influenced by a number of factors (including placental transport), antibody levels in maternal serum from the first trimester and in the blood sample from the infant were well correlated (Spearman correlation=0.76, p<0.0001). We therefore have confidence in the results based on antibody levels measured in the newborns.

Reliance on routinely acquired clinical information has its limitations, particularly with regard to the validity and reliability of diagnoses. Reassuring results have been obtained from a study that assessed the validity of schizophrenia diagnoses acquired from the Danish Psychiatric Central Register (

23). Although research diagnoses would be preferable, we believe our results can be compared with those of other studies.

A number of publications have suggested possible immunological and other mechanisms explaining the association between

T. gondii infection and brain disease (

24–

29). The association with high levels of IgG could have several explanations. High levels could reflect a recently acquired infection or a reactivated infection. One could also speculate that there is a direct effect of the IgG antibodies through molecular mimicry. It has been suggested that IgG antibodies against several infectious agents, including

T. gondii, may cross-react with epitopes in neural tissue (

30,

31), and it is known that neurological and psychiatric symptoms may be caused by antibodies crossing the blood-brain barrier in autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (

32) as well as in paraneoplastic disorders (

33). Anti-NMDA (

N-methyl-

d-aspartic acid) receptor antibodies and other specific CNS-related antibodies have been associated with psychosis and other neurological and psychiatric symptoms (

34,

35). However, at present all these explanations remain speculative. Further knowledge is needed about the potential differential effects of different strains and stages of

T. gondii . One study suggested that psychosis is particularly strongly associated with maternal infection with type I strain (

36), but this finding needs to be replicated. Future studies also should elucidate the mechanisms underpinning the association—for example, whether there is a direct effect of

T. gondii-specific IgG antibodies on the CNS, whether the effect is mediated through inflammatory mechanisms, and whether there is interaction with gene variants associated with schizophrenia.