Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has a comparatively strong level of empirical support across a range of psychiatric disorders (

1), including substance use disorders (

2,

3). Despite evidence of positive and durable outcomes (

4,

5), CBT remains rarely implemented in the range of settings where individuals with substance use disorders are treated (

6).

A number of obstacles impede the delivery of CBT and other empirically validated therapies in clinical practice, including the limited availability of professional and specialty training programs that provide high-quality training, supervision, and certification in CBT (7); high rates of clinician turnover and lack of a CBT-trained workforce in many treatment settings (8); the relative complexity and cost of training clinicians in CBT (9, 10); and high case loads and limited resources in many settings. Moreover, for the addictions and other psychiatric disorders, available evidence suggests that only a minority of individuals who could benefit from treatment actually receive high-quality evidence-based treatment (

11). Hence, computer-assisted delivery of CBT, if demonstrated to be feasible and effective, could play an important role in broadening its availability, reducing costs, improving quality, and greatly extending the reach of treatment (

12,

13).

A preliminary randomized evaluation of computer-based training for CBT (CBT4CBT) as an adjunct to standard addiction treatment compared it to standard treatment alone for 77 individuals seeking outpatient treatment for a range of substance use disorders (

22). Participants were predominantly dependent on alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, or opioids, with the use of multiple substances reported by most participants (80%). At the end of the 8-week trial, participants assigned to the CBT4CBT condition submitted significantly more urine specimens that were negative for any type of drugs and tended to have longer continuous periods of abstinence during treatment. A 6-month follow-up of 82% of the intention-to-treat sample indicated significantly better durability of effects of CBT4CBT over standard treatment for both self-report and urinalysis data (

23). The limitations of this preliminary study included the small sample size and highly heterogeneous sample that varied greatly in both type and severity of substance use at baseline.

In this article, we describe the primary outcome results from a larger randomized clinical trial of CBT4CBT in a more homogeneous, but highly challenging, clinical population, i.e., cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone. Cocaine use is among the most prevalent and intractable problems within methadone maintenance programs (

24,

25), and it is associated with a wide range of problems including HIV, hepatitis C, and multiple other morbidities (

26). Methadone treatment programs in the United States face rapidly growing censuses and patients presenting with more complex and severe problems and fewer resources with which to treat them.

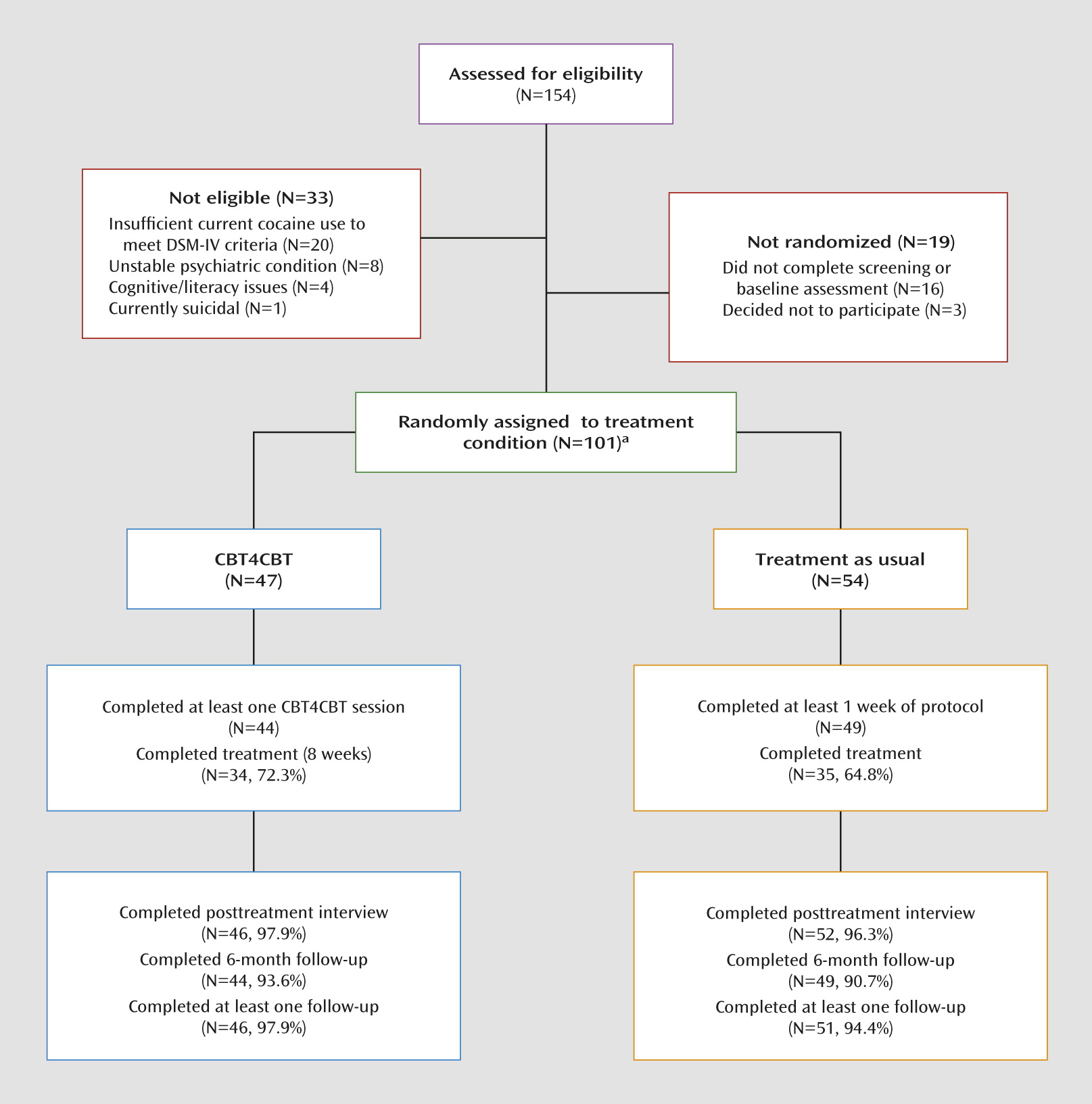

In the present trial, cocaine-dependent individuals who were stabilized on methadone were randomly assigned to standard methadone maintenance (treatment as usual) or treatment as usual plus CBT4CBT over a period of 8 weeks. Given the established efficacy of clinician-delivered CBT across a range of addictions (

2,

3) and the very limited availability of empirically validated therapies in many community-based settings, CBT4CBT was evaluated in terms of how it is most likely be used in these settings, that is, as a stand-alone addition to regular methadone services. The primary hypothesis was that individuals assigned to CBT4CBT would reduce their frequency of cocaine and other substance use and submit fewer positive urine toxicology screens than individuals randomly assigned to treatment as usual. We also hypothesized that the effects of CBT4CBT would be durable relative to treatment as usual through a 6-month follow-up. Finally, we compared the groups regarding the effects of treatment on HIV risk behavior because an HIV risk-reduction component was added to CBT4CBT to address the high rate of drug- and sex-related risk behaviors in this population (

27,

28).

Discussion

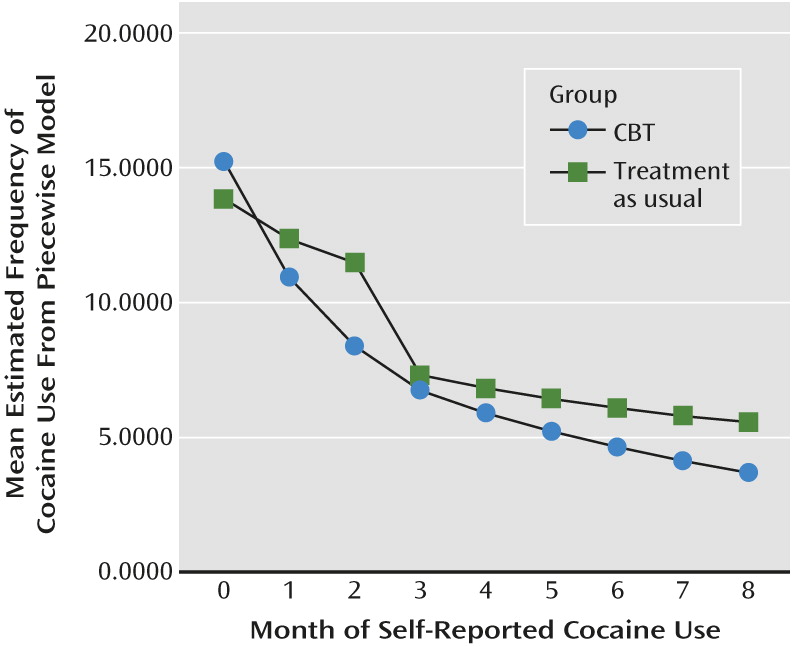

This randomized clinical trial of CBT4CBT as an adjunct to methadone maintenance therapy for 101 cocaine-dependent individuals indicated improved cocaine and drug use outcomes relative to standard methadone maintenance treatment alone (treatment as usual). Participants in the CBT4CBT condition were significantly more likely to attain 3 or more consecutive weeks of abstinence within treatment, an outcome indicator associated with better long-term cocaine use outcomes and general functioning across multiple trials. The results of a 6-month follow-up also indicated significant enduring benefit of CBT4CBT relative to treatment as usual over time. The effects of treatment on the percentage of urine specimens that were negative for all illicit drugs also approached statistical significance.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first replication, via randomized clinical trial, of a computer-assisted therapy for addiction (

20), which is significant because replication studies, while critical to the advancement of science (

36), are comparatively rare in the clinical science literature (

37). Moreover, evidence standards for both pharmacological and behavioral therapies require replication before a therapy can be considered evidence based (

38). Furthermore, we found these favorable outcomes for CBT4CBT in a particularly highly challenging population, methadone-maintained cocaine-dependent individuals, many of whom used other drugs in addition to cocaine. Other than contingency management, few behavioral or pharmacological treatments have resulted in a positive effect, much less a durable one, in this population (

39). Finally, while the overall magnitude of drug use reduction in this sample was modest, the results do compare favorably with those of other randomized trials in this population (

39–

41), and the effect sizes were comparable with those found in the initial trial of CBT4CBT (range=0.45–0.59).

The durability of effects of CBT4CBT reported for the initial trial (

23), and consistent with clinician-delivered CBT (

4), was also replicated here. Few, if any, other behavioral therapies, and no pharmacological therapies for cocaine dependence, have demonstrated durable effects once terminated. As addictions are a chronic relapsing condition, the durability of effects is a particularly important feature of any empirically validated therapy (

42).

The effect of the HIV risk-reduction module on risk behavior in this sample was more mixed. As it was the last module delivered, only half of those individuals assigned to CBT4CBT completed it (22/44). The level of self-reported drug-related risk behaviors, as assessed by the Risk Assessment Battery, fell to 0 in the CBT4CBT group by the end of treatment, but analyses did not indicate significant differences by treatment condition. An ongoing trial is evaluating the efficacy of this module, delivered alone, on the frequency of high-risk behaviors relative to standard HIV risk-reduction groups in the context of a methadone maintenance program.

The strengths of this protocol include methodological features of importance for rigorous clinical trials of computer-assisted therapies (

20,

21) and therapist-delivered behavioral therapies more broadly (

38). These include randomization to treatment, 6-month follow-up for 92% of the sample, assessment of primary outcomes using both a urine toxicology screen and validated self-report instruments, adequate sample size with intention-to-treat analyses of outcomes using appropriate statistical procedures, monitoring and reporting of adverse events, and requiring all participants to meet standardized diagnostic criteria for cocaine and opioid dependence. Moreover, in contrast to many computer-delivered interventions where low levels of adherence typically limit inferences that can be drawn regarding effectiveness (

18,

20,

43), the level of engagement with the CBT4CBT program was comparatively high, as participants completed an average of 73% of sessions offered.

This study had several limitations as well. First, CBT4CBT was evaluated as an add-on to treatment, and thus conditions were not balanced for time spent and attention. Furthermore, it cannot yet be concluded that the effects of CBT4CBT are comparable with those of individual clinician-delivered CBT. For the intention-to-treat sample, the results of study treatments on overall rates of cocaine-negative and all drug-negative urine specimens approached but did not reach statistical significance. However, the rates of negative urine screens did reach significance in the sample of individuals completing treatment, highlighting the importance of retention in evaluation treatment outcomes. Moreover, these effects were observed in the context of participants also attending group and individual counseling at least once per week while the trial was ongoing.

Overall, this extension of an initial trial of CBT4CBT to a more homogeneous (in terms of all participants meeting criteria for current cocaine dependence in addition to opioid dependence) but highly challenging clinical population is another milestone in the validation of this cost-effective (

44), easily disseminable approach. A major strength of the CBT4CBT approach itself is the ease of implementation of the computer-assisted therapy. Given the multiple roadblocks to implementation of empirically supported therapies into practice, this study confirms that CBT4CBT may provide a safe, inexpensive, and sustainable option for doing so.

The next steps for this line of research include less-tightly controlled effectiveness trials that address feasibility and outcomes when delivered in clinical settings. Another line of research would involve evaluating the efficacy of CBT4CBT with limited clinician involvement (that is, as a stand-alone approach rather than as a clinician extender) as well as direct comparisons of computer-delivered CBT4CBT with CBT when delivered by well-trained and closely supervised clinicians, all of which are ongoing in our clinics. In addition, we are exploring the utility of the program when adapted for use by other clinical populations (e.g., for alcohol-dependent or Spanish-speaking populations). Ultimately, we hope that carefully studied approaches like CBT4CBT may provide a new paradigm for treating a wide variety of addictive disorders in a broad range of settings.