Because women consistently have a higher rate of major depression than do men (

1–

5), sex differences in the etiologic pathways to major depression have often been explored (

2,

3,

6–

10). Most studies have examined single risk factors, such as marital status or quality (

5,

11,

12), stressful life events (

7), prior anxiety disorders (

13), personality (

6), and ruminative propensity (

9). Given the important etiologic role of genetic and environmental familial factors in major depression (

14–

18), delineating risk factors that differentiate the sexes would be facilitated by a design controlling for these background variables.

Results

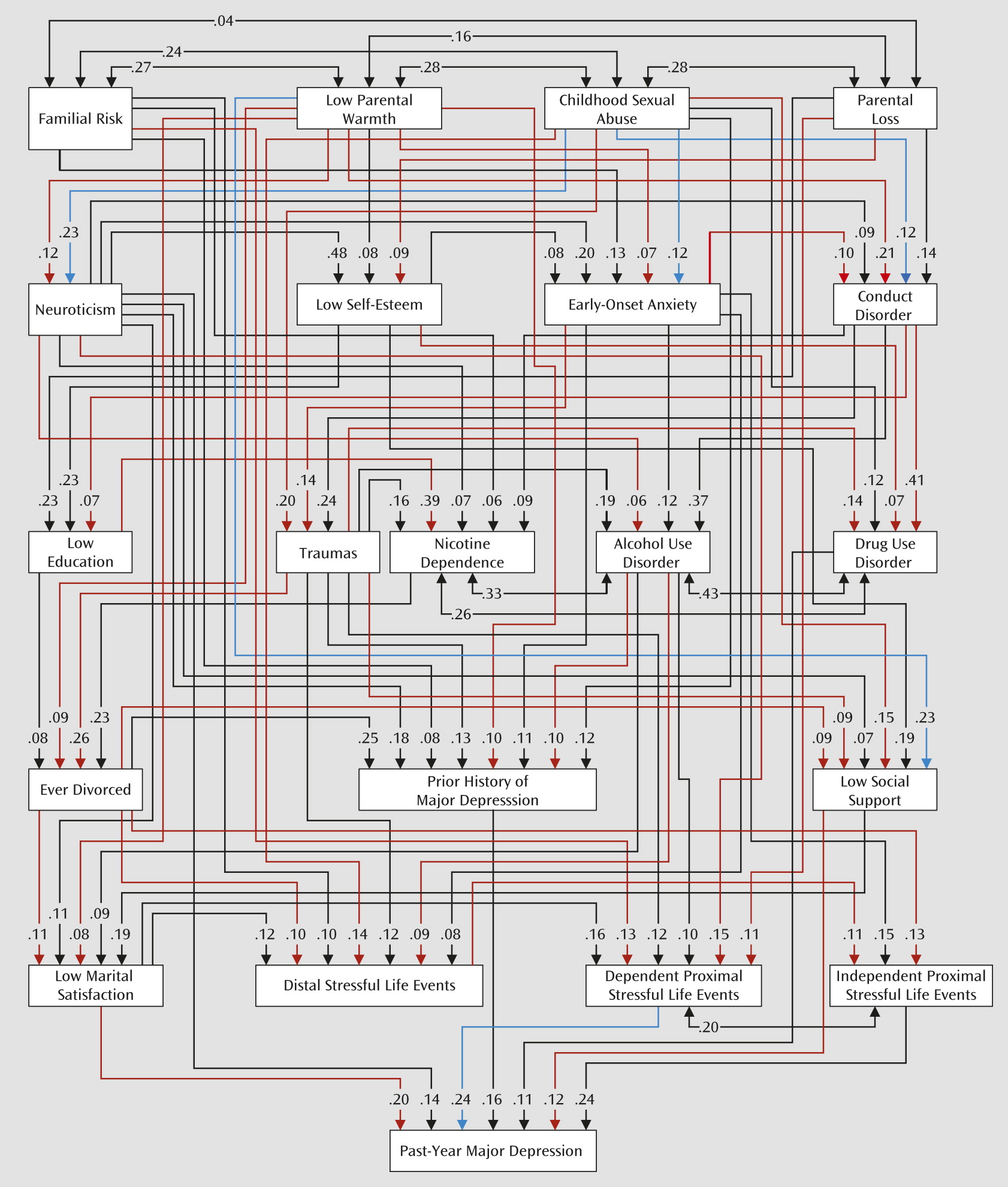

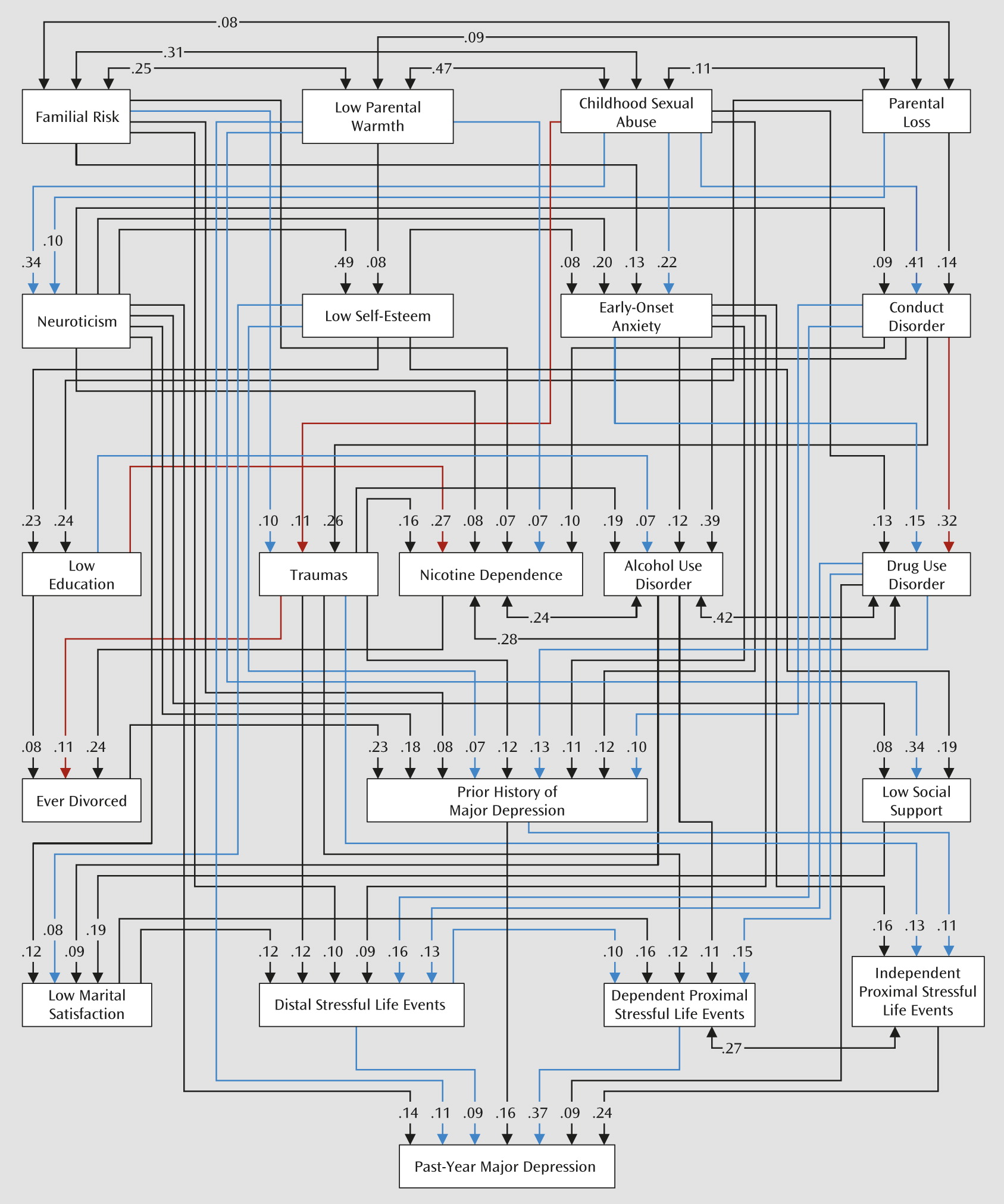

Of the 1,057 male-female twin pairs in our sample, 837 were concordant for no episodes of major depression in the past year. In 12 pairs, both members had depressive episodes. Of the 208 pairs discordant for major depression in the past year, the affected member was female in 130 (62%) and male in 78 (38%). Our best-fit model included 218 free parameters including paths (one-headed arrows in the figures) and correlations (two-headed arrows). It explained 44.5% (SE=3.9) and 48.2% (SE=3.9) of the variance in liability to major depression in females and males, respectively. The model fit indices were very good (comparative fit index=0.99, Tucker-Lewis index=0.99, root mean square error of approximation=0.01). Parameter estimates from the best-fit models are presented in

Figures 1 and

2, for females and males, respectively. Parameters estimated to be equal across sexes, greater in females than males, and greater in males than females are depicted in black, red, and blue, respectively. If a path is not present between two variables, that is because it was estimated to have a zero value. Appendix II in the online

data supplement contains the best-fit model estimate for all these paths, along with their statistical significance and the equality or nonequality of that path across sexes. Twenty-eight paths were estimated at zero in males, and 16 in females. This explains the greater density of paths in

Figure 1 relative to

Figure 2.

Results of our model can be examined in several ways. We illustrate three levels of analysis focused on sex differences in 1) individual paths, 2) all outflow paths from risk variables, and 3) total effect of risk variables on liability to major depression.

Individual Paths

A number of individual paths stood out as having substantial sex differences. For example, the paths from childhood sexual abuse to both conduct disorder and early-onset anxiety disorders were much stronger in males than females (0.41 compared with 0.12, and 0.22 compared with 0.12). The paths from drug use disorders to distal and dependent proximal stressful life events were also much more robust in males than females (0.16 compared with zero, and 0.15 compared with zero). Also, the path from dependent proximal stressful life events to past-year major depression was considerably stronger in males than females (0.37 compared with 0.24).

Paths from low parental warmth to early-onset anxiety disorders and prior history of major depression were both stronger in females than males (0.07 compared with zero, and 0.10 compared with zero, respectively). The paths from low marital satisfaction and social support to past-year major depression were both considerably more robust in females than males (0.20 compared with zero, and 0.12 compared with zero, respectively).

Risk Factors: Outflow

We next examined sex differences in the outflow of paths from individual risk factors. This is easy to do in the figures by comparing the number of red paths coming from each risk variable in females (

Figure 1) with the blue paths coming from these same variables in males (

Figure 2). We can simply classify variables into those with more red than blue paths and more blue than red paths emanating from them. Roughly, the former and latter are likely more important contributors to the etiologic pathway to major depression in females and in males, respectively. By this approach, low parental warmth, parental loss, neuroticism, lifetime traumas, divorce, social support, and marital satisfaction contribute more strongly to the pathway to major depression in females. Low self-esteem, drug use disorder, past history of major depression, and distal and dependent proximal stressful life events contribute more strongly to the major depression pathway in males.

Risk Factors: Total Direct and Indirect Paths to Major Depression

The most comprehensive way to compare the risk factors is to examine their total direct and indirect contribution to major depression in females and males. We do this in

Table 1, which depicts the total effect of the 20 predictor variables on the liability to major depression in males and females. We divided the 20 variables into four groups. For nine variables, the absolute difference in their total direct and indirect impact on major depression was less than 0.02, which we considered to reflect

minimal sex differences. For three variables, the absolute value of the difference was between 0.02 and 0.05, which we judged to reflect

modest sex differences. Four of the variables had an absolute difference between 0.05 and 0.10, which we considered to demonstrate

moderate sex differences. Finally, four of the variables had an absolute difference >0.10, which we considered to reflect

strong sex differences.

Of the three variables with modest sex differences, one had a stronger total effect in females (parental warmth) and two had stronger effects in males (childhood sexual abuse and past history of major depression). We can also trace the paths of these variables to risk for major depression in the two sexes, giving us insight into the differences in etiologic pathways. As seen in

Table 1, the difference in the impact of parental warmth was driven by its stronger impact in females on a range of risk factors, including neuroticism, early-onset anxiety, conduct disorder, divorce, past history of major depression, and marital satisfaction. For childhood sexual abuse, the greater impact on risk for major depression in males results from its stronger effect on neuroticism, early-onset anxiety, and conduct disorder. The stronger effect of past history of major depression on males results, at least in part, from its greater effect on independent proximal stressful life events.

Of the four variables with moderate differences, two had stronger effects in females (neuroticism and divorce) and two had stronger effects in males (conduct disorder and drug use disorder). The greater effect of neuroticism on risk for major depression in females was largely mediated through its greater impact in women on risk for alcohol use disorders and dependent proximal stressful life events. The stronger impact of drug use disorder on risk for major depression in males occurred through its stronger effects on past history of major depression, distal stressful life events, and dependent proximal stressful life events. The greater effect of divorce on risk for major depression in females was mediated through its stronger impact on social support, marital satisfaction, distal stressful life events, and independent proximal stressful life events.

Four variables in the model had strong sex differences, two of which had more robust effects in females (social support and marital satisfaction) and two in males (distal and dependent proximal stressful life events). These four variables all came from later developmental stages of the model and thus largely had direct effects on risk for major depression.

Specific Classes of Stressful Life Events

The two factors with the strongest impact on males relative to females were dependent proximal and distal stressful life events. To understand in more detail the nature of these sex differences, we examined the impact of the specific categories of stressors in the affected and unaffected members of discordant pairs. We focused on the category of distal stressful life events because it contained the larger total number of events and hence the greater statistical power. Three event categories stood out as having the largest differences in effect size in the affected versus the unaffected twins in the male-affected versus female-affected discordant pairs: financial problems (0.17 and 0.08), work problems (0.12 and 0.03), and legal problems (0.08 and 0.03). That is, the event categories were much more likely to be reported by the affected twin in discordant pairs when it was the male who was affected rather than the female. Of note, two stressful life event categories had a comparable excess in the affected members of the female-affected versus male-affected discordant pairs: relationship problems and serious illnesses in individuals in the twin’s close social network (0.24 compared with 0.13, and 0.11 compared with 0.01).

Discussion

We sought to clarify sex differences in the etiologic pathways to major depression as measured in the past year in a sample of 1,057 opposite-sex dizygotic twin pairs ascertained from a population-based registry. We studied a wide array of risk factors, assessed in two personal interviews at least 1 year apart. From these variables, we constructed a developmental path model with the goal of predicting the occurrence of major depression in the year prior to our second interview (

19,

20). Most informative for our analyses were the 208 pairs discordant for a depressive episode.

Our best model fit the data very well and explained nearly half of the total variance in risk for major depression in males and females. Using statistical criteria, 60% of the paths in this model differed between the sexes. We suggested three levels at which the results of this model could be usefully examined. The first two utilized visual inspection to detect individual paths with clear sex differences or the risk factors themselves that originated paths with stronger overall effects in females or in males. By these methods it could be seen, for example, that in the earliest tier of developmental risk factors, childhood sexual abuse and low parental warmth had more potent downstream effects in males and females, respectively. In the third developmental tier, drug use disorders stood out as more strongly influencing other risk factors in males. In the fourth tier, divorce and low social support were more robust predictors in females. In the final tier, marital satisfaction had a stronger impact in females, and distal and dependent proximal stressful life events in males.

However, we focused more on a comprehensive statistical view of the individual risk variables that assessed their total direct and indirect contributions to liability to major depression. While producing results broadly similar to those obtained by more informal methods, this approach was both more global and more rigorous. Focusing on total effects, our 20 risk variables for major depression could relatively easily be divided into four groups with no, modest, moderate, and large sex differences. Nine of the variables fell into the first category, with quite similar total effects across the sexes. Of the 11 risk factors in the second, third, and fourth groups, five had a stronger total impact in females and six in males.

The five risk variables with a stronger total impact of liability to major depression in women reflected personality and interpersonal relationships. Neuroticism, a widely researched and robust risk factor for major depression (

13,

27–

30), was, in our sample, over 30% more potent in its impact on major depression in women than in men. Given that the genetic risk factors for major depression and neuroticism are strongly intercorrelated (

30–

32), our findings are consistent with previous results from this sample (

33) and from a large Swedish twin sample (

34) indicating that the heritability of major depression is higher in females than males. The other four variables that more potently had an impact on depressive risk in women all reflected the quality and continuity of intimate interpersonal relationships: parental warmth, divorce, social support, and marital satisfaction.

These results are consistent with an extensive literature in the social sciences demonstrating that compared with men, women derive a larger component of their sense of self and self-worth from interpersonal relationships (

35–

37). Compared with men, women have larger social networks, are more intimate with and emotionally involved with the members of their network, and are more sensitive to adversities experienced by their network (

7,

38–

40). This point was further supported by follow-up analyses showing that the stressful life events that most differentiated affected females from affected males in discordant twin pairs were events that involved their social network. Furthermore, a number of previous studies have found that the association between social support and psychopathology is stronger in women than in men (

41–

45).

The six risk variables with a stronger total impact on liability to major depression in men were divisible into three groups, reflecting externalizing psychopathology, prior depressive history, and greater sensitivity to specific stressors. Our results with externalizing psychopathology are consistent with a wide range of studies finding that men have higher rates than women of both conduct disorder and drug abuse (

46) and that both of these disorders are associated with a higher risk for major depression (

47–

52). Our model showed that males had greater sensitivity than females to the depressogenic effects of childhood sexual abuse and stressful life events occurring in the past year. Sexual abuse in females is much more frequently researched than in males, with surprisingly few studies examining the pathogenic effects in males versus females (

53–

55). One of the few prospective studies of validated sexual abuse, in accord with our findings, reported a stronger association between abuse and major depression in men than in women (

56). Males were also more sensitive to the depressogenic effects of recent stressful life events. When we examined the specific categories of these events, the greater male sensitivity was driven by stressors associated with financial, employment, and legal problems. These results are consistent with previous evidence indicating that compared with women, men are more emotionally involved in occupational and financial success (

35,

36) and more likely to be both the perpetrators and the victims of crime (

57,

58).

At face value, several of our findings are inconsistent with the bulk of previous studies. Most studies have reported either no sex difference in rates of recurrence (

1) or a higher risk in females (

59), whereas we found that past history was more predictive of risk for major depression in men. We did not replicate earlier evidence that a large proportion of the sex differences in major depression could be explained by prior anxiety disorders (

13). Some (

60) but not all (

7) previous studies, contrary to our model-based results, found that divorce was more depressogenic for men than for women.

However, our findings are not directly comparable to previous studies, because in our complex model, the impact of individual risk factors occurred in the context of all the other variables in the model. We give one example illustrating the importance of this context. In exploring the origins of the stronger effect in males of distal and dependent proximal stressful life events, we eliminated marital satisfaction from the model. In the full model, this variable much more strongly predicted risk for major depression in females. Its removal nearly equalized the impact of stressful life events on major depression in males versus females. This occurred because low marital satisfaction was strongly correlated with adverse marital stressful life events, especially in women. So with marital satisfaction in the model, the impact of the correlated marital stressful life events in females became much less potent. This in turn was responsible for why stressful life events proved in aggregate a stronger predictor of major depression in males.

Our findings are broadly congruent with a typology of major depression developed from a psychoanalytic perspective by Blatt (

61), who noted similarities between his system and those proposed from cognitive-behavioral (

62,

63), attachment (

64), and interpersonal perspectives (

65). Blatt proposed that major depression takes two forms: “anaclitic” and “introjective.” The former arises from deficiencies in caring relationships and unmet dependency needs (e.g., “I am unlovable”), and the latter emerges from the inability to meet internal demands for self-worth and achievement (e.g., “I am a failure”) (

61). Males are substantially more likely to suffer from introjective depression and females from anaclitic depression (

61). Consistent with our findings, anaclitic depression is strongly associated with parenting deficient in nurturance, and introjective depressions with externalizing psychopathology (

61). Congruent with our results, anaclitic depressions are typically provoked by interpersonal difficulties involving rejection and/or failures to achieve expected intimacy, while introjective depressions are related to failures at key instrumental tasks, such as expected work achievements and failures to provide adequately for the family (

61).

Limitations

These results should be considered in the context of four potential methodological limitations. First, our model assumes a causal relationship between predictor and dependent variables. The validity of this assumption varies across our model. Some of the intervariable relationships that we assume take the form of A→B may be truly either A←B or, more likely, A↔B.

Second, a number of our risk factors were assessed using long-term memory and may have been influenced by recall bias. Within the limits of a two-wave design with a cohort in mid-adulthood, we minimized this problem by using multiple reporters (i.e., reports from both co-twins on variables such as familial risk, parental warmth), using objective events less susceptible to recall bias (e.g., parental loss, divorce, educational level), assessing key variables prospectively (i.e., at our first interview), and measuring a number of key constructs over the past year (including stressful life events and depressive onsets), reducing the time frame of recall.

Third, our model assumes that multiple independent variables act additively and linearly in their impact on risk for major depression. This is unlikely to be true, as we have shown in this sample (

66) that high levels of neuroticism increase sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events.

Fourth, this sample consisted of adult white twins born in Virginia. With respect to the rates of psychopathology, twins are probably representative of the general population (

67,

68). Our 1-year prevalence rates for major depression in females and males (13.4 and 8.5%, respectively) are quite similar to those reported in the National Comorbidity Survey (12.9% and 7.7%, respectively) (

46).