The increasing number of people diagnosed with dementia is a well-known phenomenon driven by an aging population and increased public recognition of its signs and symptoms (

1). The United States annual costs for health care, long-term care, and hospice care of people with dementia are expected to increase from $200 billion in 2012 to $1.1 trillion in 2050 (

2). Many of these costs are related to the long-term care required for those with severe dementia. Delaying progression to late-stage dementia has the potential of increasing meaningful time spent with those afflicted. Several studies have examined predictors of progression from onset of dementia to severe dementia (

3–

5). Factors shown to accelerate progression include younger age at onset, higher level of education, greater severity of cognitive impairment (defined as lower baseline modified Mini-Mental State Examination scores or higher clinical dementia rating scores), greater severity of behavioral disturbance, and presence of psychosis or other neuropsychiatric symptom (

3,

4). Storandt et al. (

6) showed that rate of decline on psychometric testing accelerates as dementia severity worsens, but in their study no individual test was predictive of dementia progression (i.e., nursing home placement).

Using the same population-based study utilized in the present study, the Cache County Dementia Progression Study, Rabins et al. (

5) found that female gender, less than high school education, and at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom at baseline were predictive of shorter time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia. Age at onset of dementia was predictive in that persons in the youngest (68–80 years old) and the oldest (87–104 years old) tertiles of age progressed to severe Alzheimer’s dementia faster than those in the middle tertile of age (81–86 years old). In addition, subjects with mild neuropsychiatric symptoms or at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom and subjects with worse health were more likely to progress to severe dementia or death. The present article aims to expand on this work.

The Cache County Dementia Progression Study (

7,

8) is a longitudinal study with regular reassessment of cognition and detailed collection of neuropsychiatric symptom data. Although it is known that neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with a worse prognosis in dementia (

9), the relationship between individual neuropsychiatric symptoms or clusters of neuropsychiatric symptoms and progression to severe dementia or death is not fully understood. In the present analysis, we examine the association between clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms, including psychotic and affective clusters of symptoms, and progression to severe dementia and/or death. We hypothesized that the presence of psychotic symptoms, and the individual symptom of agitation/aggression, would predict shorter time to severe dementia.

Method

Methods of the Cache County Study and the Dementia Progression Study have been described in detail elsewhere (

7,

8). Briefly, all permanent residents of Cache County, Utah, who were age ≥65 in January 1995 (N=5,677) were invited into the study. We enrolled 5,092 (90%) in wave 1 of the Cache County Study, all of whom were screened for dementia in a multistage assessment protocol. Rate of dementia was 9.6% in the prevalence wave, similar to many epidemiological samples. Individuals were reassessed at 3- to 5-year intervals (mean=3.53 years [SD=0.6]) in three incidence waves. A consensus panel made diagnoses of dementia and dementia type. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia followed the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (

10). The Dementia Progression Study (

11) limited analyses to those individuals from the Cache County Study who converted from no dementia to Alzheimer’s dementia with follow-up rates, excluding mortality, exceeding 90%. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Severe Alzheimer’s dementia was defined as a Mini-Mental State Examination (

12) score ≤10 or a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (

13) score of 3 (severe). If only the Mini-Mental State Examination criteria were met, inclusion required a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score ≥2 (moderate); and if only Clinical Dementia Rating Scale criteria were met, inclusion required a Mini-Mental State Examination score <16.

To identify potentially predictive neuropsychiatric symptoms, the 10-item Neuropsychiatric Inventory (

14) was utilized. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory is a fully structured informant-based interview that provides a systematic assessment of the following 10 neuropsychiatric symptom domains: delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation/euphoria, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor behavior. The presence of symptoms in each domain during the past 30 days was queried, and if endorsed, specific follow-up questions were asked to clarify the nature of the symptoms, including the degree of change from premorbid and treatment. Once the disturbances relevant to each domain were defined, the informant was asked about the frequency of these on a scale from 1 (occasionally) to 4 (very frequently, more than once a day). The informant was also asked to rate the severity of the behavior on a 3-point severity scale (1=mild, 2=moderate, or 3=severe). Neuropsychiatric Inventory ratings were obtained at the time of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia and scored as follows: 1=presence of at least one of the psychosis neuropsychiatric symptom domains (delusions and hallucinations); 2=presence of at least one of the affective neuropsychiatric symptom domains (depression, anxiety, and irritability); 3=presence of the individual neuropsychiatric symptom of apathy/indifference or agitation/aggression; and 4=frequency-by-severity Neuropsychiatric Inventory score across all domains trichotomized as no symptoms, at least one neuropsychiatric symptom domain score of 1 to 3 (mild), or at least one neuropsychiatric symptom domain score ≥4 (clinically significant).

To identify individual factors associated with time to develop severe Alzheimer’s dementia, we constructed unadjusted Kaplan-Meier plots for each of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory groups described above. Additionally, we ran bivariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. Based on the results from Rabins et al. (

5), the hazard models controlled for age at dementia onset, gender, education level, and General Medical Health Rating score (

15). General Medical Health Rating scores were obtained at the time of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia and were coded as excellent, good, or fair/poor. Furthermore, given results of previous studies (

16), we also controlled for apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 (APOE-ε4) genotype status, with positive designation coded if at least one ε4 allele was present. Lastly, we controlled for time between dementia onset and diagnosis (dementia duration at baseline). The same analyses were run for association with time to death. All analyses met the proportional hazards assumption and were conducted with SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk, New York).

Results

Three hundred thirty-five incident cases of possible or probable Alzheimer’s dementia were identified. The mean age at onset was 84.3 years (SD=6.4), and the mean time between dementia onset and diagnosis was 1.7 years (SD=1.3). Sixty-eight individuals (20% of the incident sample) developed severe Alzheimer’s dementia over the course of the study (1995–2009). After extended follow-up through October 21, 2010, 273 individuals were deceased. The median time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia for the sample was 8.4 years (95% confidence interval [CI]=7.6–9.2) and to death was 5.742 years (95% CI=5.423–6.061). Age at onset showed a nonlinear relationship for time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and a linear association with time to death. Global Medical Health Rating was not associated with time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia but was associated with time to death, and those with poor/fair scores had 1.6 times the death hazard compared with individuals with good/excellent scores (neuropsychiatric symptom results were not affected significantly by this).

Neuropsychiatric symptoms were common, with 50.9% of the sample having at least one neuropsychiatric symptom. The baseline percentages of the neuropsychiatric symptom clusters were as follows: psychosis cluster, 18.1%; affective cluster, 38.8%. The individual neuropsychiatric symptom domain of apathy/indifference was seen in 16.9% of individuals at baseline, and the individual domain of agitation/aggression was seen in 10%. At baseline, 25.9% of individuals had at least one mild neuropsychiatric symptom, and 25.0% of individuals had at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom.

The results of the bivariate and multivariable Cox regression models (controlled for age at dementia onset, dementia duration at baseline, gender, education level, Global Medical Health Rating, and APOE-ε4 status) are summarized in

Table 1 for hazard of severe dementia and in

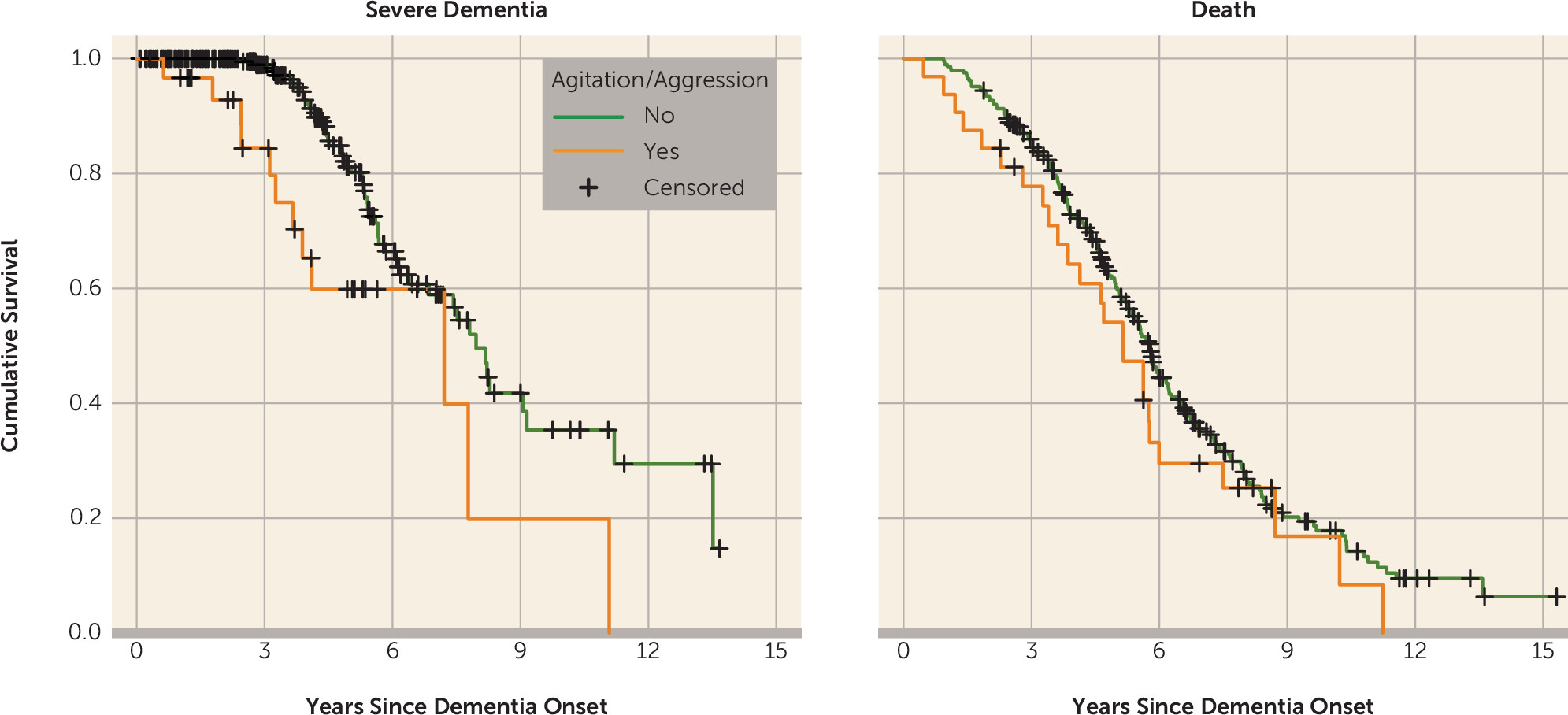

Table 2 for hazard of death. The psychosis cluster (hazard ratio=2.007, p=0.03), agitation/aggression (hazard ratio=2.946, p=0.004), and at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom (hazard ratio=2.682, p=0.001) were predictive of progression to severe dementia. The psychosis cluster (hazard ratio=1.537, p=0.01), affective cluster (hazard ratio=1.510, p=0.003), agitation/aggression (hazard ratio=1.942, p=0.004), at least one mild neuropsychiatric symptom (hazard ratio=1.448, p=0.02), and at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom (hazard ratio=1.951, p≤0.001) were predictive of progression to death. Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier plots for the outcome of severe dementia and death as predicted by agitation/aggression are presented in

Figure 1 and meant to serve as a proxy illustration for other predictors as well.

Additional models were constructed controlling for psychotropic medication use. Analyses were run for any antidepressant use (with separate analysis for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use), any antipsychotic use (with separate analyses for first- and second-generation antipsychotic use), and benzodiazepine use. Medication use was consistently not significant, and there was no appreciable change in the results (i.e., the same predictors were predictive).

Discussion

In this population-based study of individuals with incident Alzheimer’s dementia, psychosis, agitation/aggression, and clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms were predictive of earlier progression to severe dementia and death. Affective neuropsychiatric symptoms and mild neuropsychiatric symptoms were associated with earlier death but not earlier progression to severe dementia. These results expand on the analyses performed by Rabins et al. (

5), in which women, participants with less than high school education, participants with at least one clinically significant Neuropsychiatric Inventory domain, and the youngest or oldest age-at-onset cohorts progressed more rapidly to severe dementia. Age at onset showed a nonlinear relationship for time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and a linear association with time to death. Global Medical Health Rating was not associated with time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia but was associated with time to death, and individuals with poor/fair scores had 1.6 times the death hazard compared with those with good/excellent scores.

In other samples, psychosis was shown to be predictive of progression to nursing home care, but not mortality, in Alzheimer’s dementia patients (

4). Additionally, behavioral disturbance has been associated with faster cognitive decline over 24 weeks among untreated patients (

3). In this study, early agitation/aggression was a robust predictor of both accelerated progression and mortality. Other studies have commented on an apathy syndrome in Alzheimer’s disease as predictive of increased mortality (

17). In the present study, apathy was not predictive of accelerated mortality or progression to severe Alzheimer’s dementia. The treatment of specific neuropsychiatric symptoms in early dementia should be examined for its potential to delay time to severe dementia or death.

Although the causal nature of these predictive associations is not known, several possibilities exist. First, it is possible that a confounder that was not being measured in this study exists. Or perhaps localized pathology of brain regions associated with agitation/aggression or psychosis occurs in more aggressive forms of Alzheimer’s dementia. Alternatively, the presence of these neuropsychiatric symptoms may influence the care environment in some way that in turn affects progression. For example, one may speculate that the presence of psychosis or agitation/aggression may lead to behaviors, situations, and relationships that are more conducive to worsening of disease. Affective symptoms could lead to similar modification. Although not evident in this study, it is also possible that the treatment of these symptoms with antipsychotic medication increased mortality, since these drugs are associated with a 1.5- to 1.7-fold mortality increase in randomized trials and in large-scale cohort studies (

18). The present study did not show a modification in progression based on medication use of any kind.

Limitations of this study include the lack of incident case subjects <65 years old, the small number of cases with severe Alzheimer’s dementia, and the homogeneity of the population (low rates of alcohol and illicit substance abuse and low representation of nonwhite persons). In general, the fact that this is a one-time look at the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms based on frequency scores on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory without including severity scores or longitudinal measures of behavioral burden over the course from diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia to study endpoint is a limitation. Lastly, there was not a delirium screen included in the assessment because there is a very high risk of delirium in advancing dementia, and psychosis/agitation is a known manifestation of delirium (

19). A formal delirium assessment method, such as the confusion assessment method (

20), might identify undetected delirium and therefore subgroups at risk.

Strengths of the study include its epidemiologic sampling frame, a high participation rate, a prospective, longitudinal data collection, and use of state-of-the-art clinical diagnostic assessments of Alzheimer’s dementia.