Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a state between normal aging and dementia. It is defined as objective cognitive impairment relative to the person’s age, with concern about the cognitive symptoms (concern of the patient, caregiver, or clinician), in a person with essentially normal functional activities who does not have dementia (

1,

2). It affects 19% of people age 65 and over (

3). Around 46% of people with MCI develop dementia within 3 years, compared with 3% of the age-matched population (

4). People with MCI are clinically and neuropathologically heterogeneous. A subgroup of people with MCI who have progressive symptoms and particular impairment of episodic memory, termed amnestic MCI (

1), or MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease (

2) are more likely to progress to Alzheimer’s dementia.

Public health campaigns encouraging early help seeking have resulted in increasing rates of MCI diagnosis in Western countries, but we know little about how to treat or prognosticate outcomes. Neither the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) nor the U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend drug treatments, although follow-up is advised, to ensure dementia is diagnosed and care is planned early (

5). People presenting with MCI want information about their risk of developing dementia and how to reduce it.

In our recent systematic review of 41 randomized controlled trials in MCI, we found no consistent evidence for the efficacy of any intervention to reduce incident dementia or cognitive decline (

6). Theoretically, neuroprotection, treating vascular risk factors, or increasing cognitive reserve could be targeted at people with MCI who have a high risk of dementia. We concluded that cholinesterase inhibitors and rofecoxib are ineffective in preventing dementia. Cognition improved in single trials of 1) a heterogeneous psychological group intervention over 6 months, 2) piribedil, a dopamine agonist over 3 months, and 3) donepezil over 48 weeks. Nicotine improved attention over 6 months. There was equivocal evidence that huannao yicong, a Chinese herbal preparation, improved cognition and social functioning.

In the absence of consistent evidence of effective interventions from randomized controlled trials, observational cohort studies evaluating predictors of dementia in MCI are the best available evidence. Systematic reviews have reported that in mixed older populations, mostly without MCI, incident Alzheimer’s dementia has been predicted by higher homocysteine levels, lower educational attainment, and less physical activity (

7). Conflicting results have been reported for the association between dementia and other putative risk factors (smoking) and protective factors (mild-to-moderate alcohol consumption, dietary antioxidants, Mediterranean diet, and living with others) (

8). Neuropsychiatric symptoms predict MCI in cognitively normal populations (

9). These factors are possibly relevant for people with MCI, many of whom have some pathology of a dementing condition but have yet to develop clinical dementia.

In this study we synthesized evidence from longitudinal observational studies regarding modifiable risk factors that predict conversion to dementia in people with MCI.

Method

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We searched PubMed (from 1946) and Web of Knowledge (from 1900) through May 22, 2013 (updated June 5, 2014), using the terms “mild cognitive,” “cognitive impairment,” “benign senescent forgetfulness,” “age associated cognitive decline,” “age-associated memory impairment,” “age-related cognitive decline” or “mild neurocognitive disorder” together with “dementia” AND “dementia incidence,” “incident dementia,” “incidence of dementia,” “prospective,” “cohort” or “longitudinal.” No limits were applied for language or date of publication. We searched the references of included articles and excluded meeting abstracts.

We included longitudinal studies reporting potentially modifiable risk factors for incident dementia in people with MCI. We defined MCI as cognitive impairment identified from objective neuropsychological tests, in the absence of dementia or significant functional impairment. We included studies whether or not they specified the presence of subjective memory impairment. We report study results for people with amnestic MCI (requiring the presence of objective memory impairment), nonamnestic MCI, and any MCI type (requiring objective impairment in any cognitive domain). We specify whether predictors are given for all-cause dementia or Alzheimer’s dementia. We divided studies into epidemiological studies, which identified cases of MCI from the general population or in comprehensive surveys, and clinical studies, in which people already diagnosed with MCI in clinical settings were recruited, as the rates of conversion to dementia may differ. We defined a modifiable risk factor as one potentially changeable through lifestyle or existing medical treatment.

Quality Assessment

One of us (C.C.) extracted study characteristics and findings (for the data extracted, see the tables in the

data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). To assess risk of bias, two of us (C.C., A.S.) independently evaluated study quality against criteria we devised from published checklists (

10):

1.

The study subjects were a defined representative sample of participants assembled at a common point in the course of their disease or recruited to be representative of the general older population, with a response rate of at least 60% of eligible potential participants.

2.

Participants were followed up for at least a year, with at least 70% followed up.

3.

Criteria for diagnosing MCI and dementia were objective or applied in a “masked” fashion.

Disagreements were resolved by consensus. We described studies meeting all these criteria as “higher-quality” studies. We assigned grades of evidence in support of conclusions: “grade 1 evidence” was consistent evidence from higher-quality studies, “grade 2 evidence” was from a single higher-quality study or was consistent evidence from other studies, and “inconsistent evidence” was troublingly inconsistent evidence.

Data Analysis

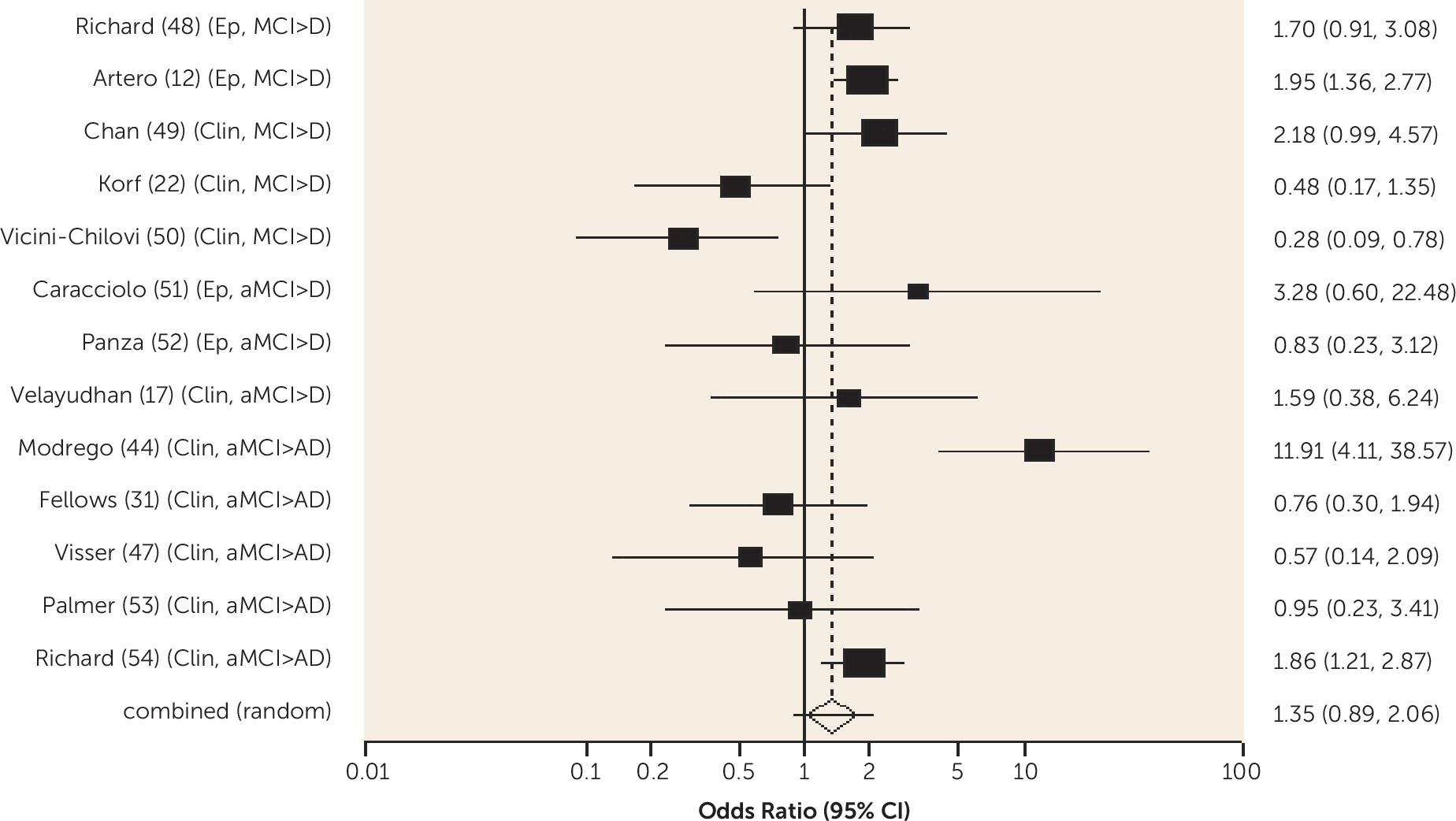

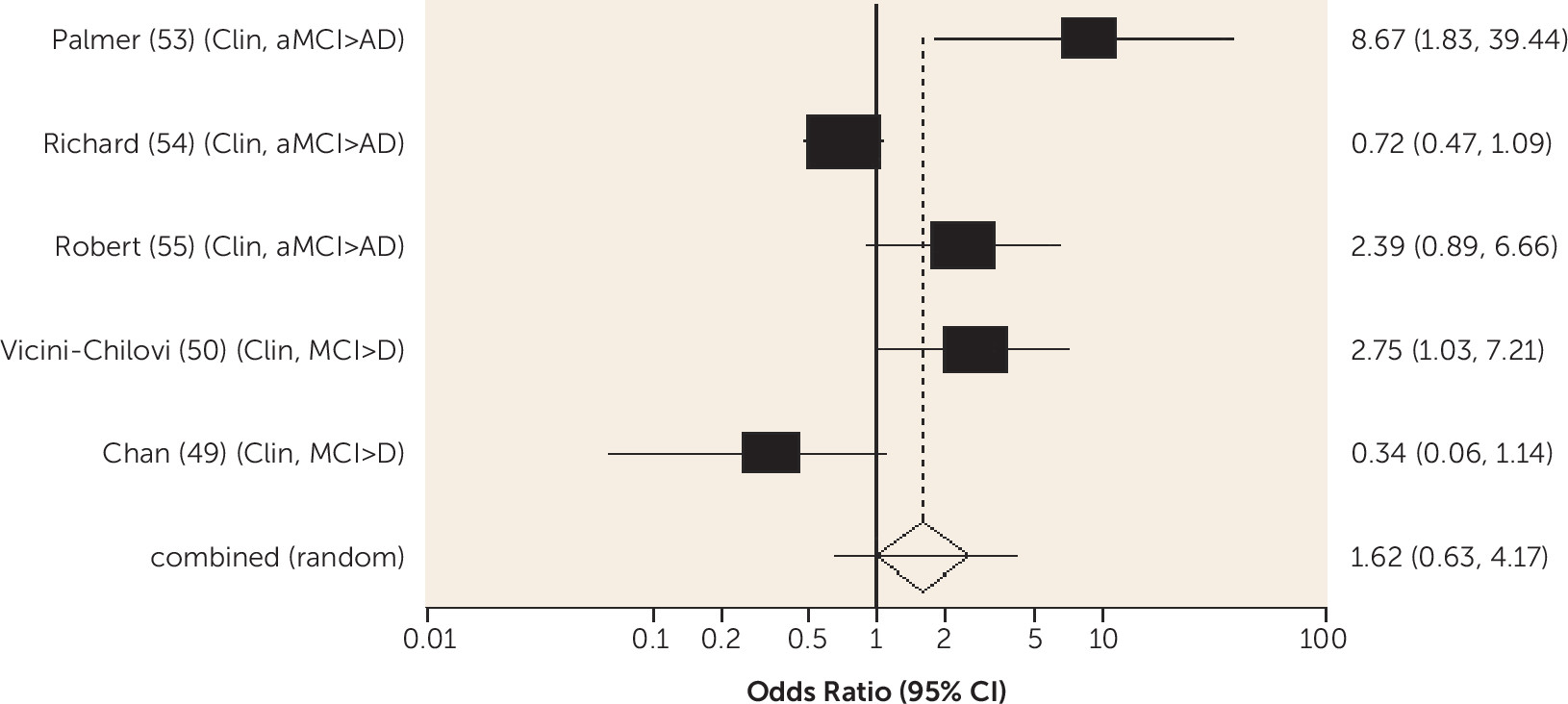

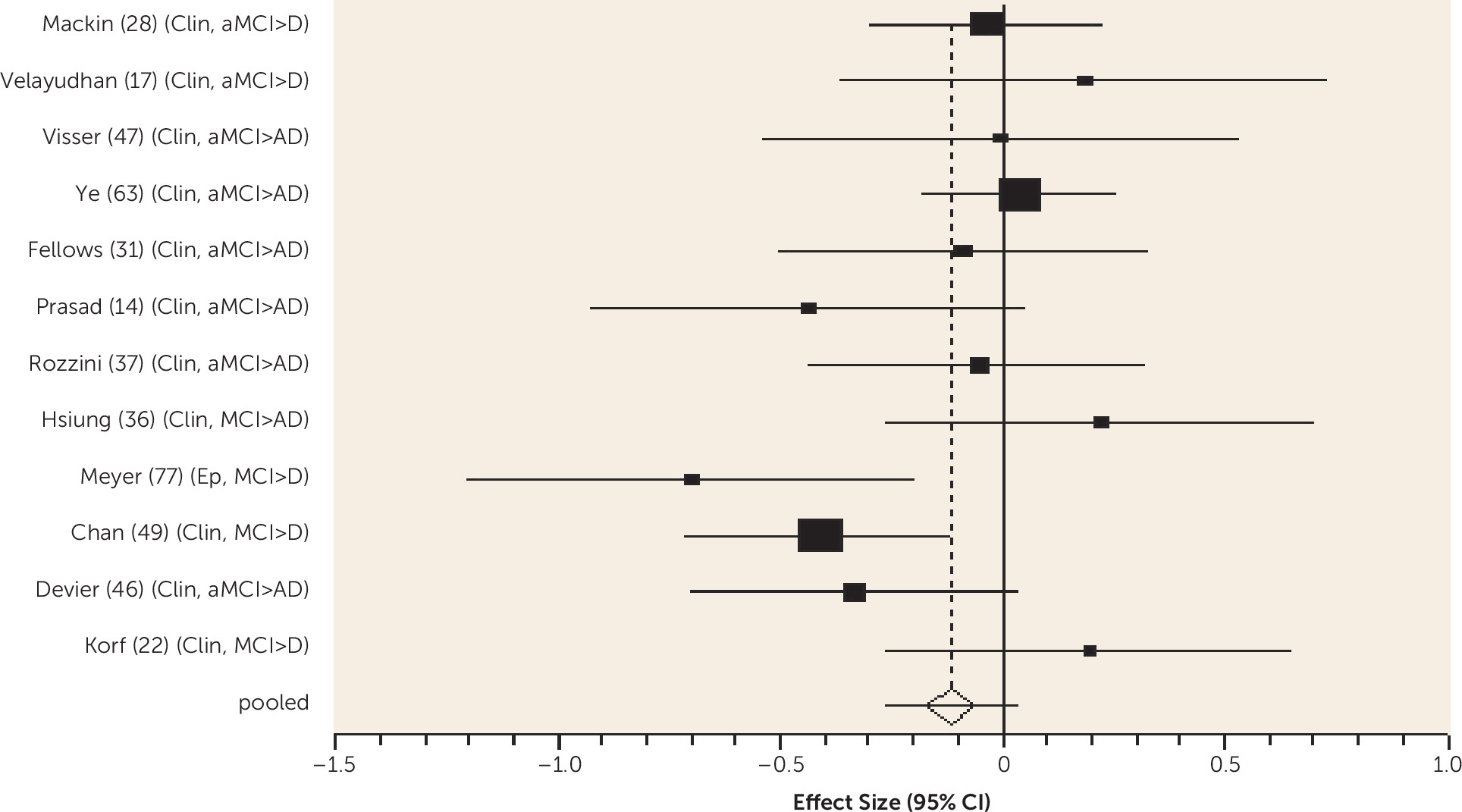

We conducted meta-analyses (random effects models) for findings where data from three or more studies could be combined. We calculated unadjusted pooled odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes and standardized effect sizes from means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes, using Statsdirect version 2.8.0 (

http://www.statsdirect.com).

Discussion

Diabetes was associated with an increased risk of conversion from amnestic MCI to Alzheimer's dementia and from any-type MCI to all-cause dementia, and the risk was lower in one study for those receiving treatment for diabetes. Metabolic syndrome and prediabetes predicted all-cause dementia in people with amnestic MCI and any-type MCI, respectively, in one study. Older people without MCI who have diabetes are known to be at increased risk of Alzheimer's, vascular, and all-cause dementia (

10). Our review shows that diabetes remains an important predictor of dementia in people with MCI and suggests it may be helpful to ensure this is detected and treated.

Diabetes and the metabolic syndrome are associated with atherosclerosis and brain infarcts, and glucose-mediated toxicity causes microvascular abnormalities. Hyperinsulinemia, a symptom of type II diabetes or result of insulin replacement, has been associated with cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s dementia (

82), probably mediated by vascular disease and possible direct brain effects. Cerebral insulin receptors are abundant in the hippocampus and the cortex, and insulin inhibits beta amyloid degradation, the main product of the Alzheimer’s dementia process (

82). Evidence of impaired insulin receptor activation in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s dementia (

83) has led to suggestions that Alzheimer’s dementia may be “an insulin resistant brain state” (

10).

Similar mechanisms could explain the finding from one of the reviewed studies that adherence to a Mediterranean diet predicts a lower risk of amnestic MCI conversion to Alzheimer’s dementia. Mediterranean diet adherence is associated with fewer vascular risk factors and with reduced plasma glucose and serum insulin levels, insulin resistance, and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation (

58). Higher folate levels predicted a lesser risk of conversion from any-type MCI to all-cause dementia, and they have also been shown to predict lower medial temporal lobe atrophy (

59). These findings are similar to those in populations not selected for presence of mild cognitive impairment: that lowering saturated fat intake (

84), increasing vegetable consumption (

85), and Mediterranean diet adherence (

86) appear to protect against dementia. We did not find that hypercholesterolemia or hypertension predicted conversion to dementia. In a systematic review of predictors of dementia in non-MCI populations, hypertension decreased risk of vascular dementia (

87), but relatively few of the studies we reviewed reported vascular dementia as an outcome. Midlife, but not late-life, total cholesterol levels have been shown to predict Alzheimer’s dementia and any-cause dementia (

88) in general populations, so for hypercholesterolemia and perhaps other vascular risk factors, intervention may be effective only if delivered before the onset of MCI.

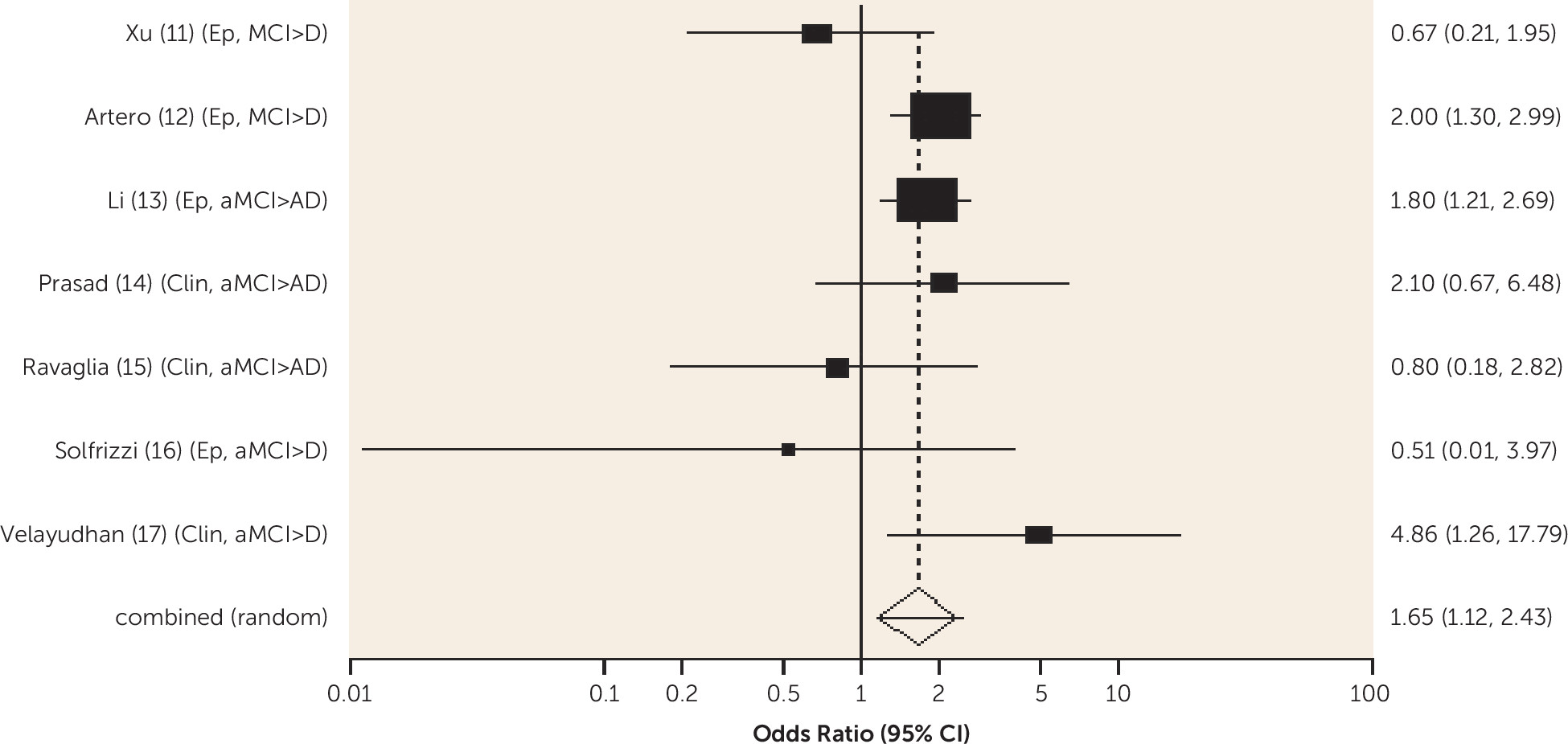

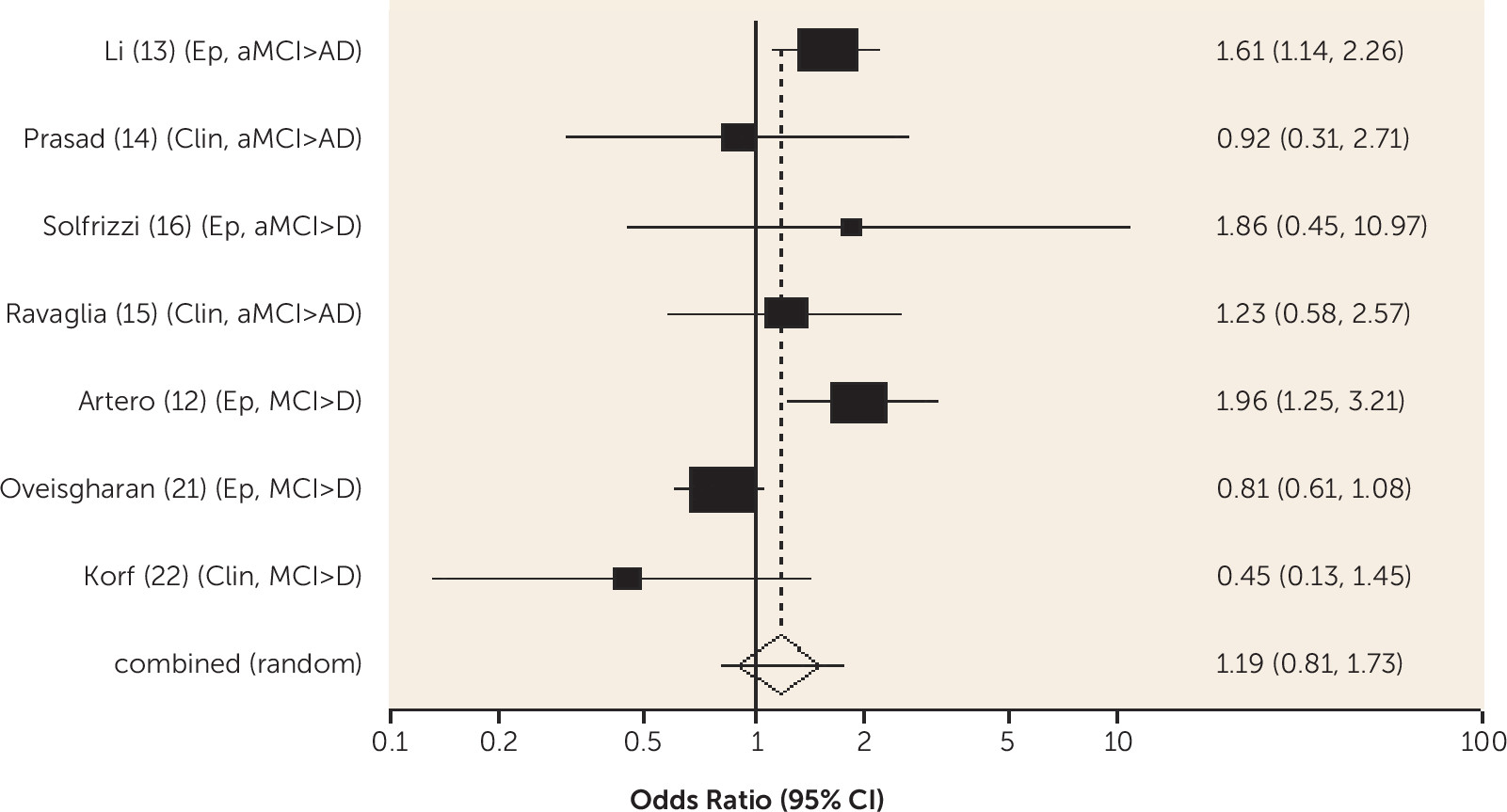

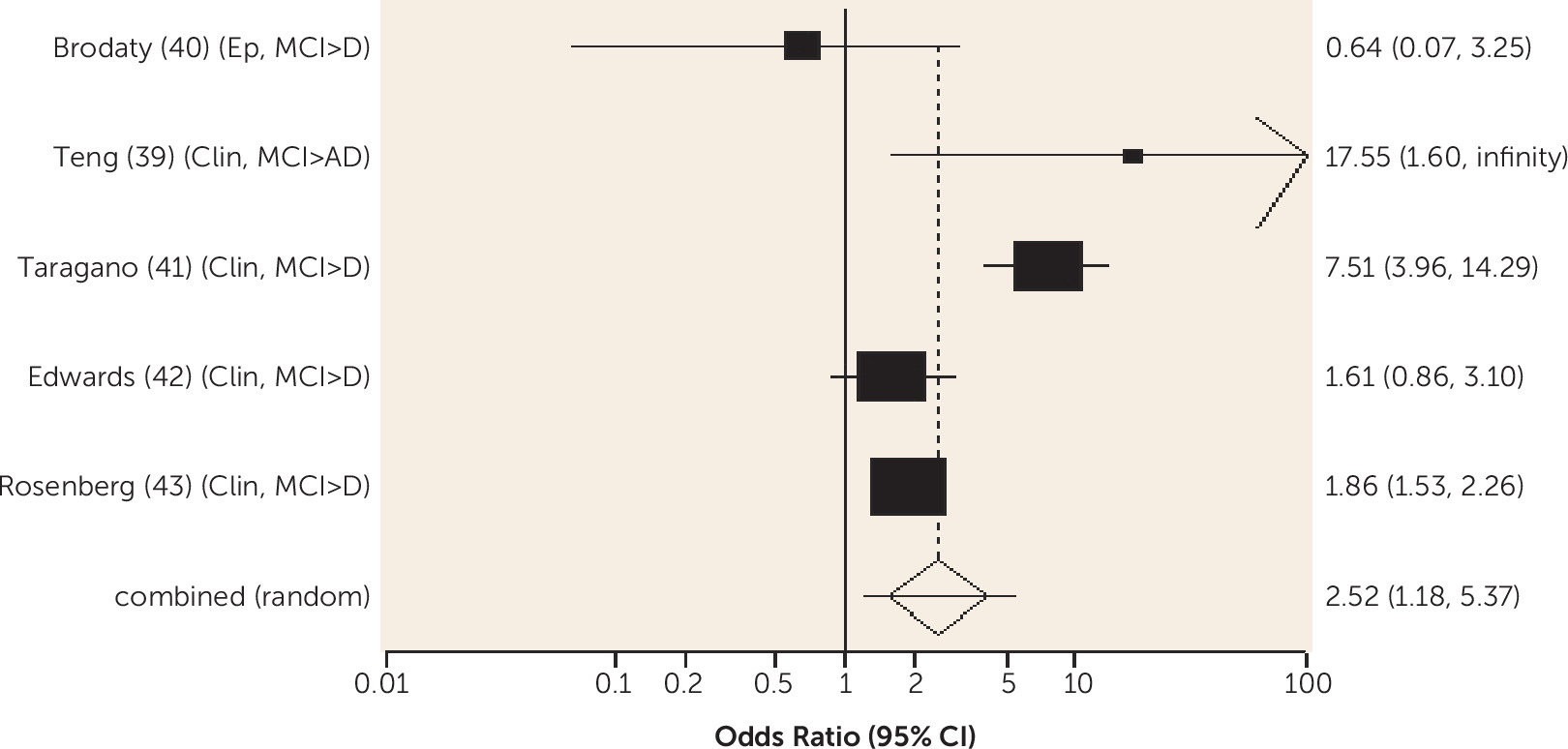

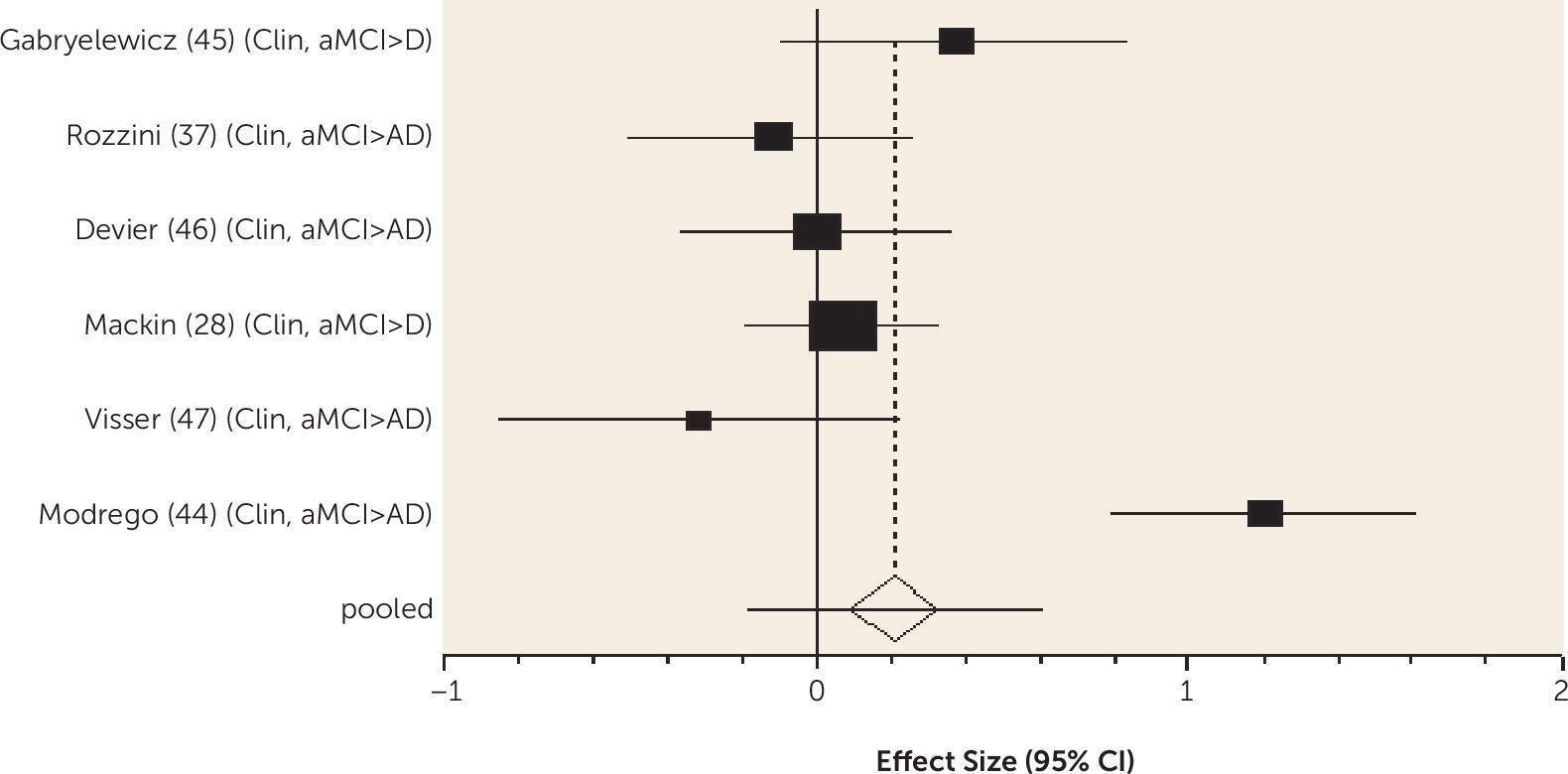

A third to three-quarters of people with MCI have neuropsychiatric symptoms, most commonly depression, anxiety, apathy, and irritability (

89). Neuropsychiatric symptoms predicted conversion from any-type MCI to all-cause dementia. Neuropsychiatric symptoms may be etiologic for dementia, for example through neuroendocrine axis activation, or they may interact synergistically with a biological factor, such as genetic predisposition. Either of these putative relationships suggests that treating neuropsychiatric symptoms could theoretically delay dementia. Alternatively, neuropsychiatric symptoms may indicate more severe pathology (

90). Greater anterior cingulum pathology in people with MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia has been associated with more irritability, agitation, dysphoria, apathy, and nighttime behavioral disturbances (

91). Serotonergic dysfunction is probably of particular relevance to neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression and aggression (

92), suggesting that serotonergic drugs might theoretically treat neuropsychiatric symptoms and reduce risk of progression; in one preliminary study fluoxetine improved cognition in people with MCI compared with placebo after 8 weeks (

93). We found that depressive symptoms predicted conversion from any-type MCI to all-cause dementia in epidemiological studies, but evidence from clinical studies was inconsistent. This might be due to lack of power in the clinical studies. In non-MCI populations, affective disorders appear to be a risk factor for dementia, as well as a prodromal symptom, in clinical and epidemiological studies (

94).

We found higher-quality evidence that amount of formal education received does not predict dementia in MCI. According to the cognitive reserve model, education delays clinical manifestations of brain pathology, so people with more education have worse neuropathology for any level of cognitive impairment (

95), and in the older general population, low education does predict dementia (

7). While the onset of MCI may be delayed in those with more education, our review indicates that progression to dementia is not delayed once MCI is diagnosed, consistent with cognitive reserve theory.

Limitations

We gave higher priority to positive findings but also described null results reported in more than one higher-quality study. Lack of evidence of prediction is not evidence of lack of prediction. Many factors found to be associated with dementia risk in populations in whom most did not have MCI, for example physical activity and omega-3 fatty acids (

7), were not studied in the included articles or were insufficiently studied, e.g., homocysteine (

7). We excluded studies where the outcome was progression of cognitive impairment rather than incident dementia. There is known to be a degree of inaccuracy in dementia diagnoses in clinical and epidemiological studies, which may have compromised the validity of some study findings. Almost all studies included any cause dementia or Alzheimer’s dementia as outcomes, rather than other subtypes; few reported vascular dementia as an outcome, and predictors, especially vascular risk factors, are likely to differ from those of degenerative dementias such as Alzheimer’s dementia.

Future Research

Associations in naturalistic longitudinal studies do not imply causation; we do not know whether preventing or treating diabetes, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and depression, where possible, or Mediterranean diet adherence might reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia or all-cause dementia. In many people with MCI, vascular risk factors and dietary habits are longstanding, and pathology may not be reversible. In the absence of effective MCI treatments, however, our findings suggest that managing components of the metabolic syndrome, dietary interventions, and social interventions are logical targets for future trials.

Methodological challenges for MCI trials include defining the study population. Only two-thirds of people with MCI progress to dementia in their lifetime (

96), limiting the power of secondary prevention studies that recruit MCI populations. The heterogeneity and instability of the MCI diagnosis militate against finding positive results in MCI trials. Availability of biomarkers may enable future trials to recruit participants according to disease process rather than clinical deficits; in a recent study, a panel of 10 proteins predicted progression from MCI to Alzheimer’s dementia with an accuracy of 87% (

97). Biomarkers may also allow participants to be recruited when the pathological process is less advanced and treatments more effective. Incident dementia is often the primary outcome as dementia prevention is a clear goal, but Schneider has suggested it is a problematic endpoint because many participants would be on the cusp of dementia and dementia onset is influenced by numerous biological and environmental factors (

98).

Conclusions

Further good-quality randomized controlled trials are necessary to identify evidence-based dementia prevention strategies, and the increasing availability of biomarkers will assist in recruitment of more homogenous populations with high likelihood of dementia conversion, improving trial efficiency. In our recent review of randomized controlled trials (

6), we found no consistent evidence that any intervention prevents conversion from MCI to dementia. The findings of this systematic review suggest that managing diabetes and components of the metabolic syndrome and dietary interventions are logical targets for future trials.