The association between birth weight and cardiometabolic health catalyzed interest in the fetal origins of noncommunicable disease (

1,

2). Importantly, the relation between birth weight and metabolic health is broadly continuous: the risk of metabolic disease declines with increasing birth weight up to the point of macrosomia, where it once again increases. More successful pregnancies (i.e., optimal fetal growth) are associated with better metabolic health. These studies (

1,

2) contributed to the emphasis on maternal health as a global priority for the World Health Organization (

http://www.who.int/pmnch) and the International Monetary Fund (

http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/mdg.htm).

Studies of fetal growth and adult health outcomes spawned the idea that intrauterine signals “program” the development of tissue function in a manner that predisposes to specific health outcomes. This idea is framed as the

developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, which suggests that the quality of fetal development shapes individual differences in the risk for chronic illness over the lifespan. The DOHaD theme is familiar in psychiatry/psychology, which emphasizes the importance of early developmental influences as determinants of mental health and human capacity. DOHaD studies reflect the importance of antenatal maternal well-being and fetal growth for individual differences in vulnerability to adverse mental health outcomes, which could inform precision medicine and intervention programs in psychiatry (

3). We briefly review the evidence for the importance of the antenatal period for neurodevelopment outcomes and suggest challenges for future research, including studies that enable the integration of findings from DOHaD studies into clinical practice and public policy.

Challenges for DOHaD Models of Mental Health

The Term “Maternal Adversity”

Measures of stressful life events, the perception of stress, depressive symptoms, and levels of state, trait, or pregnancy-related anxiety are commonly used to indicate maternal adversity. This clustering implies an assumption of common influences and/or underlying mechanisms. The evidence suggests otherwise. When studied across the normal range, maternal anxiety appears to more consistently predict neurodevelopmental outcomes than do depressive symptoms (

14,

40), although a direct comparison is difficult to operationalize. And subtle distinctions within specific forms of “adversity” seem important. For example, while trait anxiety accounts for a proportion of pregnancy-related anxiety, pregnancy-related anxiety may have greater predictive value for obstetric or child outcomes than more global measures of maternal anxiety (e.g.,

41,

42).

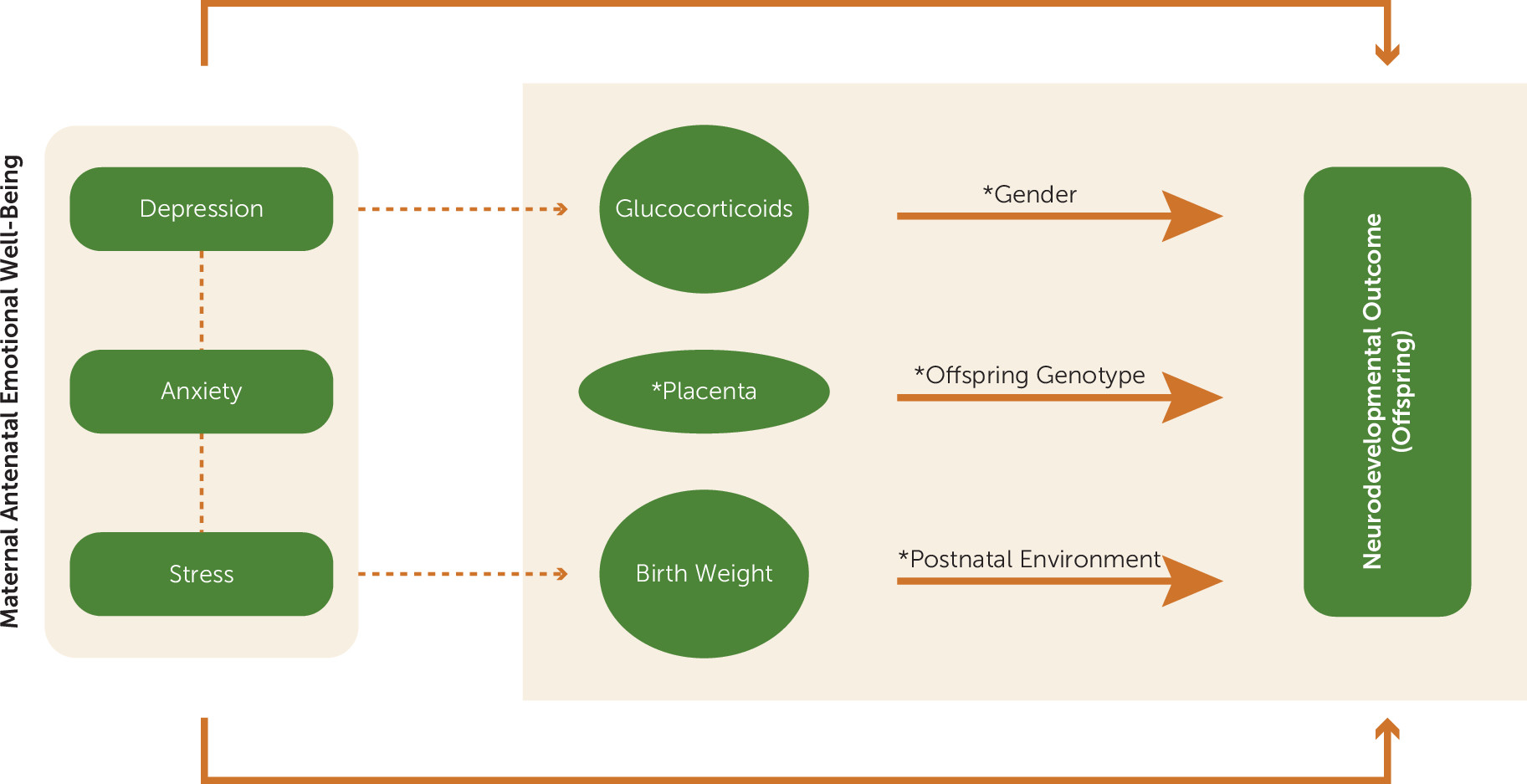

One potential source of confusion is the assumption that various forms of maternal adversity, including depression, anxiety, and stress, are associated with increased glucocorticoid levels and thus reduced birth weight and birth weight–associated outcomes. There is indeed compelling evidence for the role of glucocorticoids in fetal growth restriction. However, only a subset of patients with clinical depression show hypercortisolemia, and to our knowledge there are conflicting data on the association of anxiety with cortisol levels. Studies employing momentary assessments of maternal mood states show covariation between negative mood in pregnancy and salivary cortisol (e.g.,

43); however, a number of studies find little or no association between maternal cortisol levels and measures of maternal stress, anxiety, or depression (

25,

44–

47). Indeed, pregnancy in humans and other mammals is associated with dampened HPA stress reactivity. Detailed studies reveal no association of maternal salivary (

19), plasma, or amniotic cortisol levels (

46,

47) with either maternal stress or anxiety. Sarkar et al. (

47) reported a weak correlation between maternal anxiety and plasma cortisol, and only in early pregnancy. In contrast, O’Connor et al. (

48) reported an association between maternal depression and diurnal cortisol levels in a low-socioeconomic-status sample, while one study (

49) has reported increased cortisol levels in pregnant women with comorbid anxiety and depression. These findings suggest that the relation between maternal mental health and glucocorticoid exposure may lie within specific subgroups, including women with more severe mental health conditions.

Antenatal maternal mood, cortisol levels, and stress all predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring, but the evidence to date suggests that these factors are not necessarily associated with each other, and there is even less evidence to suggest that maternal glucocorticoid levels

mediate the effects of maternal adversity on neurodevelopment. Rather, the evidence suggests that these effects may operate through different pathways, and thus a broader survey of potential mediating mechanisms is called for (

50). Indeed, studies of the specific outcomes associated with distinct antenatal influences should enhance our ability to elucidate specific mechanisms.

Relation Between Maternal Mental Health and Birth Outcomes

Intense maternal stress, such as exposure to Hurricane Katrina, is associated with low birth weight (<2.5 kg) (

51). However, these effects are independent of maternal mental health, further underscoring the distinct influences of specific forms of maternal adversity. An extensive review (

52) reveals an influence of severe stress (e.g., death of a spouse) on offspring birth weight, as well as of factors such as social support that moderate the impact of stress, but no consistent evidence for the influence of maternal anxiety or depression (also see reference

53). The exceptions are studies showing an association between “pregnancy-associated anxiety” and birth outcomes, which again underscores the specificity of different forms of maternal “adversity.”

While extremely stressful conditions may affect birth outcomes, large epidemiological studies with community samples (e.g.,

45) have reported no association between maternal levels of depression, anxiety, or stress and either birth weight or gestational age. Likewise, a meta-analysis examining maternal depression and birth weight (

53) revealed a relation using categorical measures of depression, reflecting symptoms in the clinical range, but little or no association between birth weight and continuous measures of depressive symptoms, despite the fact that these same measures predict neurodevelopmental outcomes (see above). Interestingly, the association between clinical depression and birth outcome is strong in developing but not developed countries (

53). This finding may reflect greater access to resources for pregnant women in developed countries, such as better nutrition and prenatal health services, that buffer against compromised birth outcomes that would otherwise be apparent. Nevertheless, the existing findings suggest that while clinical levels of maternal psychopathology may be associated with low birth weight, across nonclinical populations the level of depressive symptoms or anxiety is unrelated to birth outcomes. The assumption that birth weight necessarily reflects maternal stress/adversity across the normal population, especially in developed countries, is not yet justified by the existing literature. Low birth weight seems most reasonably interpreted as reflecting a less-than-optimal intrauterine environment (

4).

Antenatal Glucocorticoid Effects

Mothers with female fetuses at risk for virilization through congenital adrenal hyperplasia are treated with synthetic glucocorticoids in the first trimester to suppress endogenous pituitary-adrenal activity. The offspring show altered cognitive performance, including inattention, as well as increased fearfulness (for a review, see reference

54). Antenatal treatment with synthetic glucocorticoids predicts increased HPA reactivity to stress in neonates born at term (

55). Antenatal glucocorticoid treatment is also associated with increased cortisol responses to the Trier social stress test in older children, an effect unique to female offspring (

56). These findings are consistent with studies reporting an association between increased maternal antenatal cortisol levels and infant HPA reactivity to stress (e.g.,

57,

58).

Glucocorticoids are also used clinically in the third trimester to advance pulmonary development in the fetus when there is a risk for preterm delivery. In contrast to the congenital adrenal hyperplasia findings, clinical trials report surprisingly few effects of antenatal glucocorticoid treatment on neurodevelopmental outcomes. These studies involve powerful synthetic glucocorticoid receptor agonists, such as dexamethasone and betamethasone, which, unlike cortisol, are poor substrates for placental 11β-HSD-2. A randomized controlled trial comparing antenatal betamethasone with placebo with follow-up in adulthood found no differences between groups exposed to betamethasone and placebo in cognitive functioning, working memory and attention, psychiatric morbidity, or health-related quality of life (

59). Similarly, a trial comparing single versus multiple antenatal glucocorticoid treatments found no differences in measures of neurocognitive function (

60). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that chronic glucocorticoid treatment during pregnancy reduced fetal growth, but with no discernible effects on neurodevelopment (

61,

62). These findings contrast with those described above, and especially noteworthy is the absence of effects of antenatal glucocorticoid treatment designed to enhance pulmonary maturation compared with treatment for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Importantly, the latter routinely involves treatment in the first trimester, whereas the former targets mid to late pregnancy. The timing of glucocorticoid treatment or exposure over the course of pregnancy, at various stages of neurodevelopment, could potentially explain seemingly conflicting findings (

63). Nevertheless, in relation to the broader DOHaD hypothesis, it should be noted that a glucocorticoid treatment in later pregnancy that reliably reduces birth weight is not consistently associated with long-term effects on neurodevelopment.

Two additional, important issues complicate our understanding of the role of antenatal glucocorticoids as mediators of maternal influences on neurodevelopment. The first concerns the unexpected specificity of effects observed in neuroimaging studies. Glucocorticoid receptors are expressed throughout the developing nervous system. Why, then, are effects of maternal mental health or maternal glucocorticoid levels specific to the amygdala, and largely the right amygdala, as well as cortical regions? Why is there such little evidence from clinical studies for effects on the hippocampus, when the rodent and nonhuman primate studies reveal consistent effects on hippocampal structure? The issue here again may be that of the timing of human corticolimbic development, although existing studies suggest that the hippocampus and amygdala show comparable developmental trajectories. Likewise, the issue of asymmetric effects, most notably in measures of amygdala volume, remains a puzzle.

A second issue is the consistent finding of gender differences. A variety of studies have reported effects of maternal cortisol levels or birth weight that are apparent only in female offspring (

11,

27,

64). Models that rely on the importance of stress mediators will need to be expanded to explain the specificity of effects in terms of gender or neurodevelopmental outcome.

Genetic Influences

The study of antenatal influences relies on measures of maternal conditions or birth outcomes that are linked to genetic variation (e.g.,

65,

66). Yet few studies have addressed the possibility that the reported associations share a common genetic basis. For example, perceived stress is a heritable trait (

67), suggesting that the effects of heritable genetic variants may account, in part, for reported associations between maternal stress and measures of child temperament, including stress reactivity, or more generally the risk for psychopathology in the offspring. Rice et al. (

68) examined this issue using a variation of a prenatal cross-fostering study in humans in which pregnant mothers were genetically related or unrelated to their child as a result of in vitro fertilization. Associations between antenatal stress and offspring outcome that are environmental in origin should be observed in both unrelated and related mother-child pairs. Antenatal stress in late pregnancy is associated with birth weight, anxiety, and antisocial behavior in both related and unrelated mother-offspring pairs, consistent with an environmental influence. In contrast, the link between prenatal stress and ADHD-like features is present only in related mother-offspring pairs and is therefore potentially attributable to heritable genetic influences or gene-environment interplay.

While antenatal maternal cortisol levels may be associated with HPA function in offspring, the interpretation is subject to concerns of heritable genetic influences. HPA function shows an intriguing, context-dependent heritability (

69). High heritability of HPA reactivity is evident among children in families with low adversity, but not in families with high adversity. High familial adversity is associated with greater cortisol reactivity to stress. Since the majority of children enrolled in community-based studies are likely drawn from low-adversity settings, the association between antenatal maternal cortisol and HPA function in the offspring may reflect heritable genetic influences. Moreover, since glucocorticoids are a well-established mechanism for low birth weight, these same considerations might influence the interpretation of associations between birth weight and HPA function. The concern for genetic mediation is underscored by a study showing that among seven confirmed genome-wide loci that account for variance in birth weight, with effects comparable to maternal smoking, three are also associated with cardiovascular (

ADRB1) or metabolic disease (

ADCY5, CDKAL1) (

66), suggesting that the well-documented relation between birth weight and cardiometabolic outcomes may partly reflect common underlying genetic features.

There has been surprisingly little emphasis on the moderating effect of offspring genotype in studies linking birth weight or maternal stress to neurodevelopment. The consideration of heritable genetic variation is not simply an issue for the interpretation of epidemiological studies. The inclusion of genetics in DOHaD research models provides the opportunity to expand the breadth of research focusing on antenatal environmental influences to discern the degree to which such effects are moderated by offspring genotype. Existing studies reveal that associations between birth weight and child socioemotional development are moderated by variants in multiple genes implicated in serotonergic or dopaminergic function (e.g.,

TPH2,

HTR2A,

SCL6A4, DRD4) (

70–

72), and stratification by genotype yielded effect sizes beyond those commonly reported for studies of birth weight alone. Qiu et al. (

22) reported that offspring

COMT genotype actually determined the nature and regional specificity of the influence of antenatal maternal anxiety on cortical morphology.

One approach to examining genetic variation is to compare the moderating influence of the maternal and offspring genotypes. For example, the

BDNF genotype of the infant, but not that of the mother, moderates the influence of antenatal maternal anxiety on genome-wide DNA methylation (

21). Indeed, a survey of interindividual variability in DNA methylation across the genome in umbilical cord samples shows that the vast majority (∼80%) of such variation is principally determined by an interaction between maternal condition or birth outcome and infant genotype (

73). The increased risk of major depressive disorder among individuals born small (<2.5 kg) is greater among children of depressed than nondepressed parents (

74). The implication is that the effect of birth weight on later depression is greater among those with a depressed parent, which suggests moderation by genetic influences. A polygenic risk score calculated from genome-wide association studies of major depressive disorder could be used in such studies as a measure of individual cumulative genetic vulnerability (

75). Studies of the relation between maternal conditions and birth outcomes might likewise benefit from genetically informed designs. Hypofunctional 11β-HSD-2 variants, for example, might define instances where increased maternal stress is more likely to be associated with increased fetal cortisol exposure (

35,

37,

76) and thus greater effects on birth weight and neurodevelopment. These considerations suggest that the transition of DOHaD science from observational studies to those of biological mechanisms will require the integration of genetic information into developmental models. Since vulnerability is seemingly best defined by measures of both environmental risk and genetic predisposition, the inclusion of genetic information is also important for the most precise targeting of interventions.

Clinical Significance

Maternal mental health and birth outcomes predict child health and development. But are these effects functionally relevant and clinically informative? The impact of maternal emotional well-being on child outcomes has been assessed (

14,

15). After controlling for multiple potential confounders, children of mothers with increased antenatal anxiety show a twofold increase in behavioral problems. Importantly, these effects equate to an approximate doubling of the population prevalence of childhood psychiatric disorders (

15). A similar analysis showed that prenatal maternal stress accounted for 17% of the variance in childhood cognitive abilities (

77). The situation is less clear for birth weight. Individuals born small show worse outcomes in terms of school achievement test scores, use of disability programs, residence in high-income areas, and wages (

10). These findings suggest an economic impact. However, children born small are also more likely to be born into poverty to mothers of lower education (

10), as well as to mothers with high-risk lifestyles that include smoking and increased alcohol consumption, which predict low birth weight. In the 1958 British cohort study of 10,845 children, birth weight accounted for 0.5%−1.0% of the variation in math scores, whereas social class accounted for 2.9%−12.5% (

78). Another study (

15) showed that obstetric outcomes (birth weight and gestation age) explained <1% of additional variance in child emotional/behavioral difficulties when maternal mental health and socioeconomic status variables were accounted for. These studies suggest that although the impairments in neurodevelopment associated with low birth weight are functionally relevant, the magnitude of the impact uniquely associated with fetal growth per se remains unclear.

The relevance of variation in fetal growth across the population for clinical medicine and intervention programs must be determined. This issue is not unique to the study of mental health outcomes. Despite the many years since the initial reports linking fetal growth to the metabolic syndrome, it remains unclear to what extent fetal development might account for clinical cases of metabolic or cardiovascular disease: What percentage of the patients with the metabolic syndrome were born small? Does fetal growth retardation predict differential clinical outcomes or, importantly, suggest alternative treatment strategies? Studies addressing these issues should occupy the forefront of future DOHaD research.

Fetal Neurodevelopment and “Meta-Plasticity”

There is considerable evidence that the influence of intrauterine factors on neurodevelopment is modified by postnatal environmental conditions. Low birth weight predicts adolescent depression more strongly in girls with a history of adverse postnatal experiences, which suggests that the effects of prenatal experiences are conditional on the postnatal environment (

11). Likewise, the association between birth weight and hippocampal volume is moderated by the quality of parental care (

27). Socioeconomic status appears to moderate the effects of fetal growth restriction on irritability and impulsivity (

79). The well-established association between birth weight and ADHD is absent in suburban communities (

80), suggesting effects that are context dependent, and an enhanced quality of maternal care eliminates the association between birth weight and ADHD symptoms (

81). Likewise, mother-infant attachment moderates the influence of maternal glucocorticoids on socioemotional development (

82). These findings reveal that the consequences of fetal adversity on child development are dependent on the quality of the postnatal environment.

Indeed, various forms of prenatal adversity may actually increase the sensitivity of the developing organism to the influences of the postnatal environment (

83). This “meta-plasticity” refers not to the influence of antenatal adversity on any specific outcome, but rather to the degree to which the developing organism is susceptible to subsequent environmental influences. The quality of intrauterine environment might explain, in part, the wide diversity among children in the degree to which developmental outcomes are influenced by prevailing context (

84), a possibility that could inform and improve early interventions strategies.

In the studies noted above, the effects of socioeconomic status or maternal care are greater among low compared with normal birth weight offspring (

27,

78–

81). The effect of breastfeeding on cognitive development is greater in low compared with normal birth weight children (

85). Likewise, there is evidence for the idea that the impact of interventions or of high-quality day-care programs may be greater among children born at low birth weight (e.g.,

86). This meta-plasticity may extend to the influence of antenatal glucocorticoids. The effect of socioeconomic status on long-term memory is greater among children exposed to antenatal glucocorticoid treatment (

87).

This issue is of considerable importance for the evaluation of treatment outcomes of prevention/intervention programs, as the failure to account for differential vulnerability could underestimate the “treatment” effect among more vulnerable individuals. These considerations also underscore the importance of longitudinal approaches with sample sizes sufficient to effectively stratify subjects according to risk factors. Such studies might better address the issue of clinical significance, as environmental effects could be evaluated on the basis of adversity in earlier developmental periods.

Conclusions

Research on the fetal origins of individual differences in neurodevelopment has attracted attention to a period of development previously undervalued in importance for later mental health. DOHaD studies provide an empirical basis for multidisciplinary programs across obstetrics/gynecology, neonatology, pediatrics, neuroscience, and psychiatry/psychology and are essential for a comprehensive understanding of the relation between maternal health, fetal growth, and neurodevelopment. This same partnership is critical for clinical programs that target maternal health.

Fetal development clearly matters. Nevertheless, the science of fetal origins of psychopathology faces important challenges. First, current models suffer from the inclusion of multiple antenatal maternal conditions in the broad category of “adversity.” Symptoms of depression or anxiety or responses to stressful circumstances are not synonymous in their underlying biology. Nor do these conditions readily map onto variations in fetal growth. Studies that relate specific maternal conditions and birth outcomes to specific neurodevelopmental consequences bear greater promise in our studies of underlying mechanisms.

Second, glucocorticoids are strongly linked to fetal growth, and there is compelling evidence for the association between maternal cortisol levels and neurodevelopment. However, there is surprisingly little evidence for an association between levels of maternal emotional well-being and increased HPA axis activity. Maternal anxiety or depression may increase transplacental passage of glucocorticoids (e.g.,

76,

88), but this possibility awaits direct study. Studies of glucocorticoids or any candidate mechanisms must also account for the unexpected specificity in the effects of antenatal maternal mental health as well as for the prominent effects of gender (

Figure 1). Future research will need to resolve why a glucocorticoid treatment regimen sufficient to produce a decrease in birth weight does not necessarily affect neurodevelopment. It will also need to investigate why the amygdala, and in particular the right hemisphere, is so sensitive to the influences of antenatal maternal mood.

Third, future research must clearly assess the clinical relevance of the individual antenatal factors that influence fetal neurodevelopment. Nanni et al. (

89) have provided evidence for the role of childhood maltreatment as a significant predictor of illness course and treatment outcomes in depression: childhood maltreatment predicts treatment resistance to antidepressant medications, although not psychotherapy. A comparable level of evidence is lacking for antenatal exposures and should assess the degree to which such factors independently account for variation in mental health outcomes as well as the degree to which such factors might inform clinical practice (

14). Future research should also focus on the potential importance of antenatal factors for the effective identification of high-risk individuals in early childhood for prevention programs.

Finally, it is difficult to imagine how environmental influences could operate in the absence of genetic moderation. Environmental signals influence brain development and function through effects on intracellular signaling pathways, the activity of which inevitably varies across individuals in part as a result of sequence-based, heritable genetic variation. Thus, the influence of antenatal maternal conditions on neurodevelopment will vary as a function of the genotype of the offspring. Studies that incorporate the analysis of genomic variation may identify gene networks that moderate the impact of antenatal environmental influences and thus elucidate the underlying biological pathways.

These are formidable challenges, and they are not unique to studies of environmental influences occurring during fetal development. However, progress in our understanding of the origins of mental health will depend on our ability to successfully meet the demands of research that focuses on neurodevelopmental outcomes at the level of the individual child.