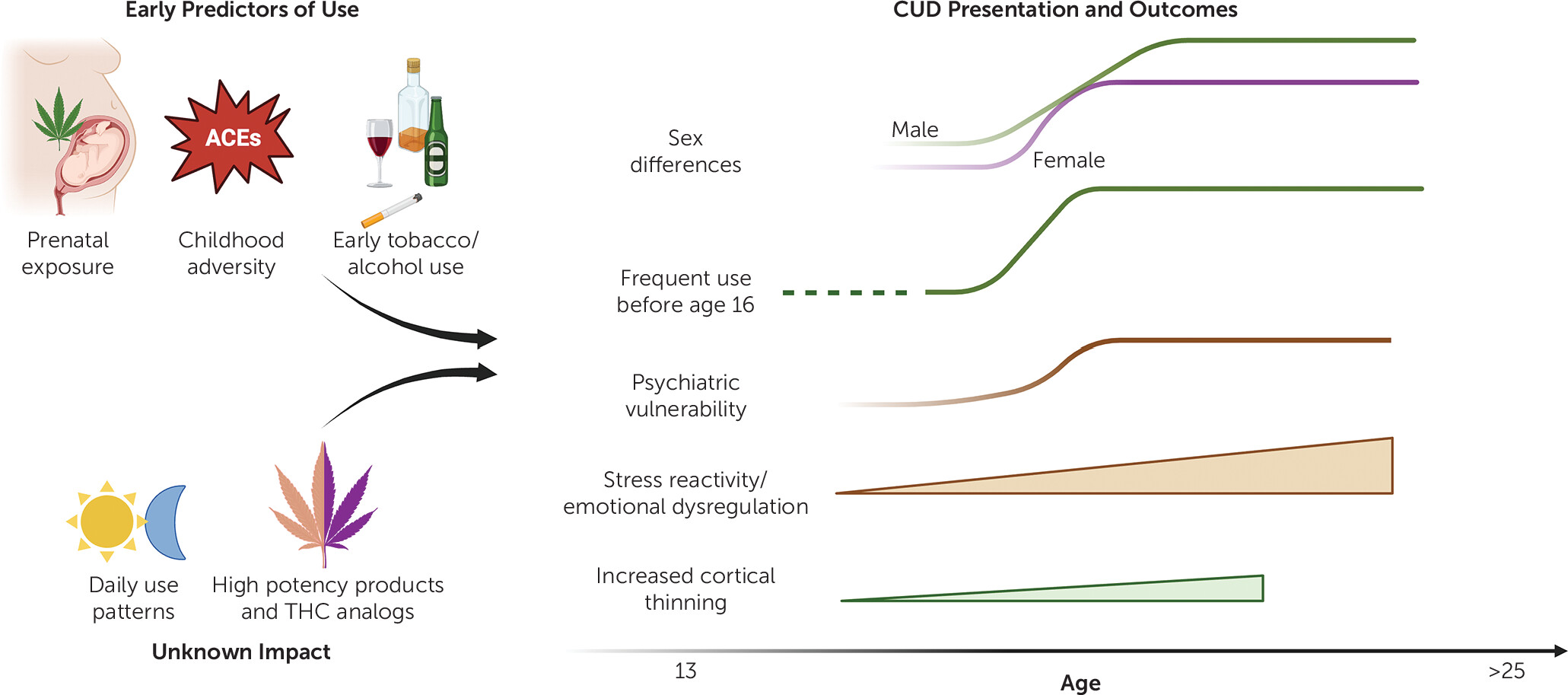

Commercialization of cannabis products in legal markets has led to a sharp rise in THC potency, as well as availability and utilization of high-THC products, such as dab pens, wax, or shatter, among youth (

2). Though recent studies have shown that high THC potency may be associated with increased risk of developing CUD (

5), the neurodevelopmental impact of using

current THC concentrates during adolescence remains understudied. To date, the integration of research findings has also been compromised by diverse and inconsistent measures of exposure. This is in part due to the wide array of cannabis products, with many individuals regularly using more than one type of product. Moreover, very limited information is known about the

type of cannabis and cannabinoid products being used including a recently identified rare but extremely potent cannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabiphorol (THC-P), now widely available commercially (

35). Information is also lacking regarding the proliferation of hemp-derived products that circumvented state and federal laws in manufacturing cannabinoids such as Δ

8-THC other THC analogs (e.g., Δ

10-THC and hexahydrocannabinol [HHC]), through the chemical conversion of cannabidiol, a non-intoxicating cannabinoid (

36). The same challenges are evident with precursor products such as THC-acid (THCA) which converts to Δ

9-THC upon heating (

36). Though adolescents and young adults often think that these popular new THC-analogs are “healthier,” they can produce cannabimimetic effects similar or greater than Δ

9-THC (

36,

37). The mental health implications expected with these new THC analogs requires significant monitoring and research attention.

Another factor critical for CUD is the developmental pattern of cannabis use relevant to severity of use. Most epidemiologic studies query the prevalence of cannabis use within a set time frame, most often past 30-day, past year, or lifetime. As noted above, the frequency of cannabis use is associated with increased risk of developing a CUD (

20), but some clinicians misapply frequency of use as a measure of CUD severity. Consideration of factors used with identifying alcohol use disorder may yield new insights into high-risk patterns of cannabis use and the development of CUD. For instance, cannabis use in the morning (e.g., “eye opener,” “wake and bake”) may be more indicative of problematic use. Such information is, however, not often considered within screening and diagnostic constructs of CUD. Similarly, binge patterns of cannabis use have not been characterized, and the impact of episodic consumption of large amounts of high potency THC on the development of CUD is unknown. Alternatively, improved characterization of an individual’s use beyond timeline follow-back may be accomplished via boarder adoption of subjective measures of cannabis use (

38), though further studies are needed to validate such measures and establish a consensus guideline for future research.