Social communication deficits, manifested by poor knowledge of social skills or the inappropriate use of these skills, are a core symptom domain of autism spectrum disorders (ASDs); there are few effective treatments that target this domain.

1 Older adolescents and young adults with ASDs are especially affected by these deficits as they transition to adult life; moreover, they are a severely underserved population, despite a recent surge in research and treatment services for patients with ASDs.

2Finding medications to treat core symptom domains of ASDs, such as impaired sociability and stereotypic behaviors, has been difficult.

3 A role for glutamatergic dysfunction in the pathophysiology of ASDs has been shown.

3,4 For example, transgenic mice with deficient expression of N-methyl-

d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor subunit NR

1 or an up to fivefold diminished affinity of the NMDA receptor for the obligatory glycine coagonist have impaired sociability.

5–7 Glycine

B site agonists work cooperatively with glutamate to promote channel opening and Ca

2+ conductance. Importantly,

d-cycloserine (DCS), a partial glycine

B agonist, improved sociability in several mouse models of ASDs in a standard social paradigm and was also reported to improve sociability in children with ASDs.

8–12 DCS has been used in multiple other human child and adult studies with dosages ranging from 30 mg to 500 mg daily.

13 No therapeutic responses were observed with doses <50 mg, whereas doses >250 mg were without any greater therapeutic effect and were associated with intolerable side effects, including exacerbation of psychosis in patients with schizophrenia. This latter side effect may reflect antagonism of the strychnine-insensitive glycine binding site by DCS at the higher doses.

13–16The sensitivity of the obligatory glycine

B coagonist binding site may change with daily administration of DCS as a result of “agonist-induced desensitization.”

14,17 Thus, in this pilot investigation, we compared the efficacy of a pulsed once-weekly administration versus daily administration of DCS in order to address the important issue of tachyphylaxis or receptor desensitization, which is a loss of efficacy due to tonic exposure to DCS as a result of daily administration.

17 Importantly, a pulsed administration has been shown to be effective in terms of facilitating extinction in human subjects treated for obsessive-compulsive disorder with cognitive-behavioral therapeutic interventions.

18 In addition, a pulsed administration has been studied in patients with schizophrenia, a disorder in which DCS has been administered in order to target presumed NMDA receptor hypofunction.

14,19Specific aims included replication of the preliminary findings of Posey et al.

10 in older adolescents and young adults with ASD whose total IQs were ≥70 and possessed sufficient expressive language to describe effects on social ability. In addition, we wished to determine whether there were any advantages of daily dosing over a once-weekly pulsed administration of DCS. Thus, the two dosing regimens were explored using a double-blind randomized design (i.e., 50 mg daily versus 50 mg weekly).

Methods

Participants

Male and female participants (aged 14–25 years) with a documented DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of ASD from their treating psychologist/psychiatrist whose symptoms met a cutoff on the ASD Checklist based on DSM-IV-TR criteria completed by the parent were enrolled. The checklist was developed by one of the coauthors (K.H.) and served to assure that groups were comparable with equivalent numbers of discrete symptoms but were not necessarily similar with respect to symptom severity. All subjects were required to provide documentation of a normal physical examination and laboratory screening (comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count) as well as an ECG and IQ test (IQ>70) within a year before starting the study. IQs were measured using the Wechsler Abbreviated Score for Intelligence.

20 Medication and therapy regimens were required to remain stable for 4 weeks before beginning the study.

Individuals were ineligible for the study if they had active suicidal thoughts or major medical problems (liver disease, kidney disease, seizure disorder, heart disease, severe anxiety or depression, or psychosis), were pregnant or breastfeeding, or were taking isoniazids or ethionamides.

Participants agreed to maintain their stable treatment regimen (including medications and/or therapy) while enrolled in the study and to refrain from drinking alcohol for the duration of the trial. All female participants were given a pregnancy test at the start of the study and were excluded if the test yielded a positive result. Subjects with abnormal ECG results were referred to their cardiologist/primary care physician for medical clearance before starting the study.

All subjects or guardians (legally appointed representatives) provided voluntary informed consent or assent, as appropriate. This study was approved by the Eastern Virginia Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Design

The study was a double-blind randomized 10-week trial, consisting of 8 weeks of active drug at either weekly or daily dosing and a 2-week follow-up visit, conducted between August 2010 and March 2012. Two dosing strategies, 50 mg weekly (placebo taken for the remaining 6 days of the week) and 50 mg daily, were compared. Subjects were required to attend four visits: baseline, midpoint of active drug administration at 4 weeks, end of active drug administration at 8 weeks, and follow-up at 10 weeks. The study measures were completed at each visit. Treatment compliance was monitored by a diary card, which subjects and/or caregivers completed on a daily basis.

Study Measures

The Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC), which has been used to assess drug and other treatment effects (psychopharmacologic, behavioral, and other) in severely intellectually disabled individuals and persons with ASDs, was administered at every visit.

21–24 The ABC is normed from childhood to adulthood and has 58 items rated on a Likert scale. Factor analyses of the ABC resulted in five factor subscales: 1) irritability, agitation, or crying; 2) lethargy/social withdrawal; 3) stereotypic behavior; 4) hyperactivity or noncompliance; and 5) inappropriate speech. The five subscales were analyzed independently in this study. The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) was administered at every visit. The SRS measures the severity of autism in an individual’s natural setting and focuses on social awareness, social information processing, capacity for reciprocal social communication, social anxiety/avoidance, and autism preoccupation.

25–27 The following social perception tests of the Advanced Clinical Solutions cognitive test battery

28 were administered at every visit: 1) in the affect naming test, subjects shown pictures of adults experiencing various emotions are tasked with pointing to which of several affective terms best describe the emotions (e.g., happy, sad, angry, afraid, surprised, disgusted, or no feeling/neutral); and 2) in the prosody-face matching test, subjects listening to audiotapes of people speaking are tasked with pointing to which of several faces best represents the feeling expressed by the audiotape.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics included means and standard deviations for continuous variables as well as frequencies for categorical variables. Linear mixed-effects models were used to assess changes in clinical outcomes over time according to group assignment by testing for the additive effects of group and time as well as group × time interaction. The t test was used to test for differences in baseline demographics between the two groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to test for differences in gender and number of clinical responders between the two groups. Principal component analysis was used to produce exploratory biplots of baseline measures and patient improvement from baseline to week 8 to look for patient subpopulations that may be particularly receptive to treatment. A significance level of alpha=0.05 was used for all analyses. The p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Twenty-one subjects were enrolled in the study and randomized to either the daily or weekly dosage of DCS using a block randomization procedure. Twenty subjects completed the study. One subject discontinued DCS after the baseline visit due to minor depression, resulting in 20 total subjects in trial.

Table 1 provides a summary of the demographics of subjects in the trial by dosage group. All subjects maintained a stable medication and therapy regimen throughout the trial. Most subjects were taking a serotonin-enhancing drug such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, buspirone, or clomipramine (N=13) and/or a stimulant such as extended-release methylphenidate, methylphenidate, atomoxetine, or dextroamphetamine/amphetamine (N=9). Three subjects were taking low-dose risperidone or aripiprazole, one subject was taking clonidine, and one subject was taking oxcarbazepine.

Linear mixed-effects models were fit to each of the scores to assess change from baseline to week 8 (end of medication).

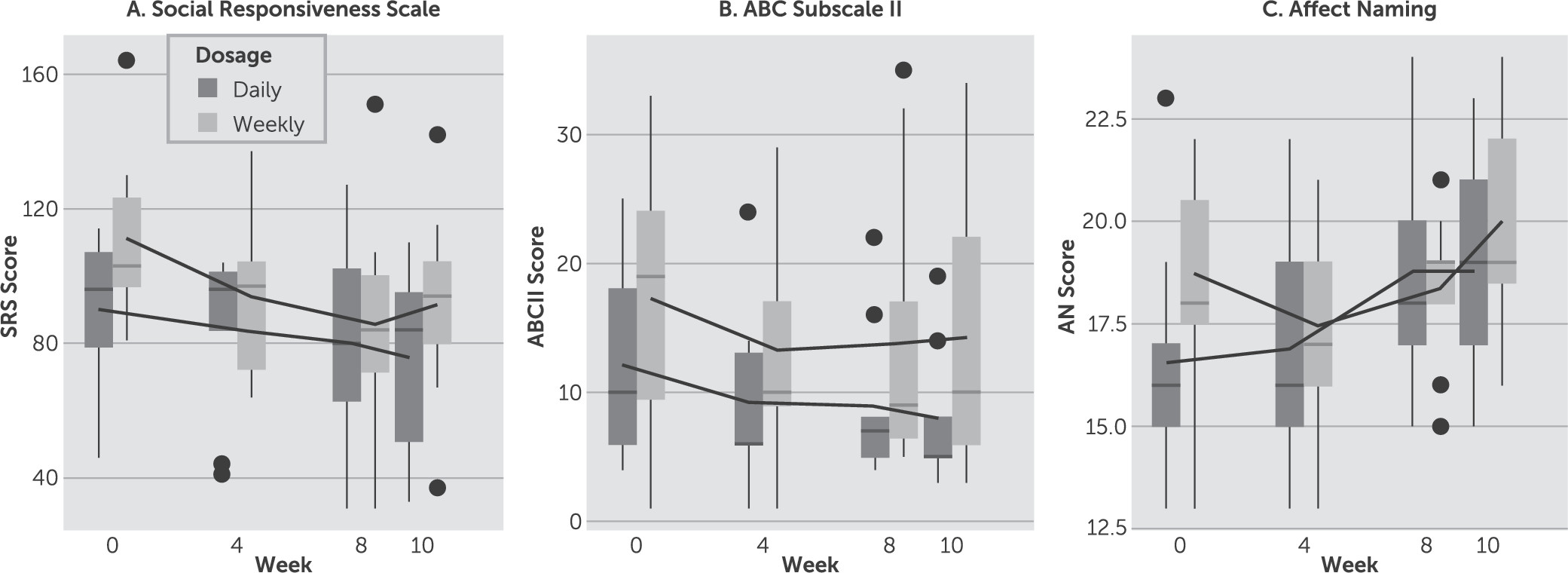

Figure 1 shows box plots of response over time from baseline to week 10 for both dosage conditions for the SRS, ABC subscale II, and affect naming test with mean trend lines added for each group. Our primary outcome measure of efficacy was the SRS, which was used to assess severity of social impairment.

27 Both daily and weekly dosing strategies showed a significant downward trend when modeled separately (p=0.004 and p=0.001, respectively). However, we were unable to detect a significant group × time interaction between the two groups when included in the same model (p=0.34). If we instead define a threshold for clinical response equal to change >1 SD (16 points), we again see no difference in the proportion of clinical responders in each group (three of nine in the daily group, seven of 11 in the weekly group) as assessed by Fisher’s exact test (p=0.37).

All other measures similarly showed statistically significant decreasing linear time effects but all group × time interactions were not statistically significant. Because there were no significant differences in efficacy between dosing strategies, the groups were combined and results are shown in

Table 2. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was computed to test for a significant positive association between the SRS and ABC subscale II (r=0.55, p<0.001). The SRS and the ABC subscale II are two major scales used in conjunction to assess social function in multiple studies of treatment response in patients with ASD.

Linear mixed-effect model analysis was restricted to time on medication; little to no worsening or improvement was observed from week 8 to follow-up at week 10 on the SRS and the ABC subscales.

Figure 2 shows exploratory biplots of baseline scores and improvement from baseline to week 8 for all measures using principal component analysis. The first biplot in

Figure 2A clusters patients by baseline scores with arrows pointing in the direction of worse than average scores. We can see that patients 1, 9, and 12 had poorer than average baseline scores, especially for the SRS and ABC subscale II, whereas patients 3, 4, and 8 had poorer than average scores especially on the other ABC subscales and the affect naming test.

Figure 2B similarly clusters patients by change in scores from baseline to week 8 with arrows pointing in directions of better than average improvement. We can see that many of the patients, particularly 1, 3, 4, 8, and 9, cluster similarly in both plots, indicating that in most cases, patients with poorer baseline scores generally saw greater improvements from baseline to week 8 than those with more favorable baseline scores.

Importantly, DCS was very well tolerated; only transient spontaneously recorded side effects were noted on diary cards kept by the patients and their caregivers, which were not reasons for medication discontinuation (

Table 3). There was a slightly higher incidence of side effects in the daily dosage group than the weekly dosage group, but the difference was not found to be statistically significant by Fisher’s exact test (p=0.65). Four subjects requested to continue DCS after the study ended.

Discussion

Treatment of the core social deficit in ASDs has been elusive. This study provides proof of concept/proof of principle that targeting the NMDA receptor in the context of a comprehensive, individualized interdisciplinary treatment plan holds promise for addressing this core symptom domain. The results suggest that a once-weekly pulsed dosing strategy can be adopted in future clinical trials, which will enhance compliance, minimize the potential for side effects, and reduce costs. DCS was safe and well tolerated in this study sample. Importantly, medication trials that include the older adolescent and young adult population with ASDs are rare.

Positive therapeutic effects of DCS were detected with parent rating scales (i.e., the ABC and SRS), as well as objective tests completed by the subjects (i.e., the Social Perception–Affect Naming subtest). Improvement was not detected on Social Perception–Prosody-Face Matching, a complex subtest that requires correctly matching auditory and visual expressions of emotional responses. For all scales, no group × time interactions were statistically or clinically significant, which may be partially attributable to small group sample sizes. Exploratory cluster analysis suggests that patients with more severe baseline symptoms may have more to gain from DCS than those with milder symptoms at baseline. Factor analysis of the SRS and ABC subscale II may clarify the symptom clusters responsible for the prosocial effect of DCS. In addition, analysis of the Social Perception–Affect Naming subtest may clarify which emotions are better discriminated as a result of NMDA receptor activation. Consistent with the known heterogeneity of the phenotype of ASDs and their outcomes, the biplots revealed individual subjects responding best on different outcome measures.

NMDA receptors are enriched in anatomic nodes within circuits subserving sociability (e.g., frontal cortex and hippocampus), and diminished NMDA receptor–mediated neurotransmission is associated with impaired sociability.

29 Increased signaling activity of the mammalian target of rapamycin is a pathogenic mechanism implicated in several syndromic forms of ASDs that are due to effects of single mutant genes (e.g., tuberous sclerosis complex, type 1 neurofibromatosis, and fragile X syndrome), and dysregulated mammalian target of rapamycin signaling may also be involved in nonsyndromic presentations.

30–33 Interestingly, NMDA receptor activation contributes significantly to the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling activity.

34–39 Conceivably, at least some of the prosocial effects of DCS are mediated by regulatory effects of NMDA receptor activation on mammalian target of rapamycin signaling activity.

An early dose-escalating trial of DCS added to first-generation antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia suggested that beneficial effects on negative symptoms observed a U-shaped dose-response relation, with maximal improvement occurring at 50 mg/day.

40 Moreover, worsening of psychosis was associated with high serum concentrations and doses of ≥250 mg/day.

13 Theoretically, daily (350 mg/week), as opposed to once-weekly (50 mg/week), dosing of DCS is more likely to be associated with receptor desensitization and tachyphylaxis to its therapeutic effects, as well as excitotoxicity. The differences between low and higher absolute and cumulative doses (the latter are associated with daily administration) could also reflect differences in the sensitivity and location of NMDA receptors containing NR

2C versus NR

2A or NR

2B subunits. DCS behaves more like a full agonist at NMDA receptors containing NR

2C subunits, which are enriched on cerebellar granule cells and are also found on interneurons in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

13 Thus, beneficial effects of the once-weekly dose of DCS (50 mg) may reflect stimulation of NR

2C-containing receptors in areas of the brain implicated in the circuitry of impaired sociability, whereas higher absolute or cumulative doses (e.g., 350 mg/week) may reflect both antagonistic effects of this partial agonist at NR

2A- and NR

2B-containing receptors and, possibly, desensitization of NR

2C-containing receptors. In any event, this investigation supports a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pulsed weekly DCS administration in a larger sample of older adolescents and young adults with ASDs.

Limitations of this study include a lack of placebo control although subjects were randomized and raters were double blinded. A small sample size with high variability in the outcome measures limits the conclusion that there is no difference between dosing strategies. Bias from parental reporting is also a consideration; however, one objective measure, the affect naming test, showed positive results as well. It is also possible that a combination of a serotonin-enhancing drug with DCS may be responsible for the positive results because several of our responders were taking one of these medications.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Hampton Roads Community Foundation (Grant 20101482). The funding source had no involvement in the research. Bayview Pharmacy provided the study drug, and the Eastern Virginia Medical School Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences provided funding for the study drug, staff, and supplies.

Previous Presentation: NCDEU, May 29, 2013, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.