Mental health problems are more frequently misdiagnosed among patients from ethnic minority, immigrant, and refugee groups than among native-born patients who are not from minority groups (

1–

3). Misdiagnosis may involve failing to recognize the presence of a mental health condition (nonrecognition or underdiagnosis), identifying a disorder when none is present (overdiagnosis), or mistaking the diagnosis for another condition (misidentification). Overdiagnosis may occur when culturally normative behavior is mistaken for psychopathology, whereas normalizing pathology may result in underdiagnosis (

4,

5). More generally, misdiagnosis can occur when clinicians fail to elicit crucial diagnostic information or misinterpret it because of insufficient attention to social, cultural, and contextual factors that shape symptom expression and illness behavior (

6,

7).

In the United States, several studies have reported that black patients are more likely than white patients with similar clinical profiles to receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia rather than an affective disorder (

8–

12). Other risk factors for misdiagnosis include language and communication barriers, which can result in racial and ethnic differences in the clinical information recorded (

12). Factors in the larger society that influence pathways to care may also bias the diagnostic process. For example, greater numbers of black men enter psychiatric care through social services and legal systems rather than through referral from family physicians (

13).

Although researchers have advocated use of structured interviews and strict diagnostic criteria to reduce errors in cross-cultural psychiatric assessment (

8,

14), this may be insufficient to eliminate misdiagnosis, in part because patients may express distress in ways that do not fit conventional categories (

6,

7,

12,

14). Alternatively, improving the cultural competence of mental health workers has been emphasized (

15–

17), including more culturally nuanced approaches to cross-cultural diagnosis, use of language interpreters and culture brokers, and use of supplementary symptom reporting scales or cultural formulation interviews (

18–

21). The cultural formulation, introduced in the fourth edition of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (

22), is a potentially important tool to support cultural competence in diagnostic assessment (

23–

25).

Reports indicate that the cultural formulation may be a useful tool in intercultural work (

26–

31), but there has been limited evaluation of the impact of its systematic use on clinical outcomes (

18,

32). This study examined the use of cultural formulation in the process of diagnostic reassessment of patients at a specialized outpatient cultural consultation service (CCS) (

33). The objectives of the study were to determine whether CCS assessment resulted in changes in diagnoses of psychotic disorders among patients from diverse ethnic and immigrant or refugee backgrounds and to identify sociodemographic characteristics and contextual factors associated with changes in diagnoses of psychotic disorders.

Methods

Procedure and patients

The study consisted of a retrospective analysis of medical records of patients seen at the CCS of the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, from June 1999 through July 2009. The CCS receives referrals from primary care, mental health care, and other health professionals for clarification of diagnosis, treatment planning, problems in treatment adherence, or other cultural issues in clinical care. The core CCS team includes a clinical coordinator, three part-time psychiatrists, and a network of interpreters and culture brokers, including health professionals, anthropologists, and persons knowledgeable about specific cultural communities (

33). Cultural consultation typically entails two steps. The first step involves assessment of the patient, family, and other key informants by the CCS consultant (a psychiatrist or psychologist) with the collaboration of a culture broker (a bicultural mental health professional or layperson) and an interpreter if needed. For assessments, consultants are asked to use an expanded version of the

DSM-IV-TR outline for cultural formulation that includes issues related to migration, ethnic identity, family systems, and developmental issues (

33). The second step entails a multidisciplinary case conference at which the psychiatrist presents the case and the culture broker presents additional pertinent cultural background information for discussion and diagnostic formulation of the case with the multidisciplinary group of mental health professionals.

Patient inclusion criteria were 16 years of age or older and having a completed case discussion and psychiatric evaluation by the CCS team. Ethics approval for the study was given by the Jewish General Hospital research ethics committee.

Study variables

Intake and final diagnoses.

The intake diagnosis was the

DSM-IV-TR (

22) diagnosis provided by the referring clinician. The final diagnosis was assigned by the CCS team after assessment at the CCS case conference. Typically, a case often had a principal diagnosis and one or more differential diagnoses at both intake and after the CCS consultation. For this study, we chose the principal diagnosis at intake as the study intake diagnosis and the principal final diagnosis from the CCS as the study final diagnosis. Furthermore, we classified patients as having either a psychotic disorder (including schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, shared psychotic disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified [NOS]) or a nonpsychotic disorder. Patients with intake diagnoses of bipolar affective disorder or of major depression with psychotic features were included in the nonpsychosis group, because these disorders are categorized as affective disorders in

DSM-IV-TR.

Patterns of diagnostic change.

Intake diagnoses were compared with CCS diagnoses. Patients were classified into one of three categories: no change; change to nonpsychotic disorder, when an intake psychotic disorder diagnosis was changed to a nonpsychotic disorder diagnosis; and change to psychotic disorder, when an intake diagnosis of a nonpsychotic disorder was reassessed as a psychotic disorder.

Sociodemographic data.

Characteristics included patients' age, gender, marital status, country of origin, years of residence in Canada, and immigration status in Canada, which dichotomized persons as permanent residents (citizens, landed immigrants, and accepted refugees) and nonpermanent residents (refugee claimants or asylum seekers, students, and persons with temporary visas).

Race-ethnicity.

Patients' race and ethnicity data were based on self-identification, as recorded in case notes. Race-ethnicity was categorized as white (Euro-Canadian), black (Afro-Caribbean and African), Asian (East Asian, Southeast Asian, and South Asian) and other (Canadian First Nations, Hispanic, and Arab or Middle Eastern) to reflect major ethnoracial groupings in Canada (

34).

Referral source.

We categorized referral source into four groups: family physician or primary care provider; psychiatrist; clinical psychologist; or social worker, occupational therapist, or other nonmedical professional. Information on interpreter use in the CCS assessment was also recorded.

Data analysis

Bivariate comparisons of patients with and without changes in diagnosis on demographic and other variables were conducted with chi square tests. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to assess factors associated with change in diagnoses. Predictor variables (gender, ethnicity, language, length of residence in Canada, and referral source) were selected a priori on the basis of a literature review. Discrimination and calibration of the logistic regression models were assessed with the c index and Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test statistic, respectively (

35). Analyses were conducted with SPSS, version 16.0 (

36). All statistical tests were two-tailed with significance level set at p<.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

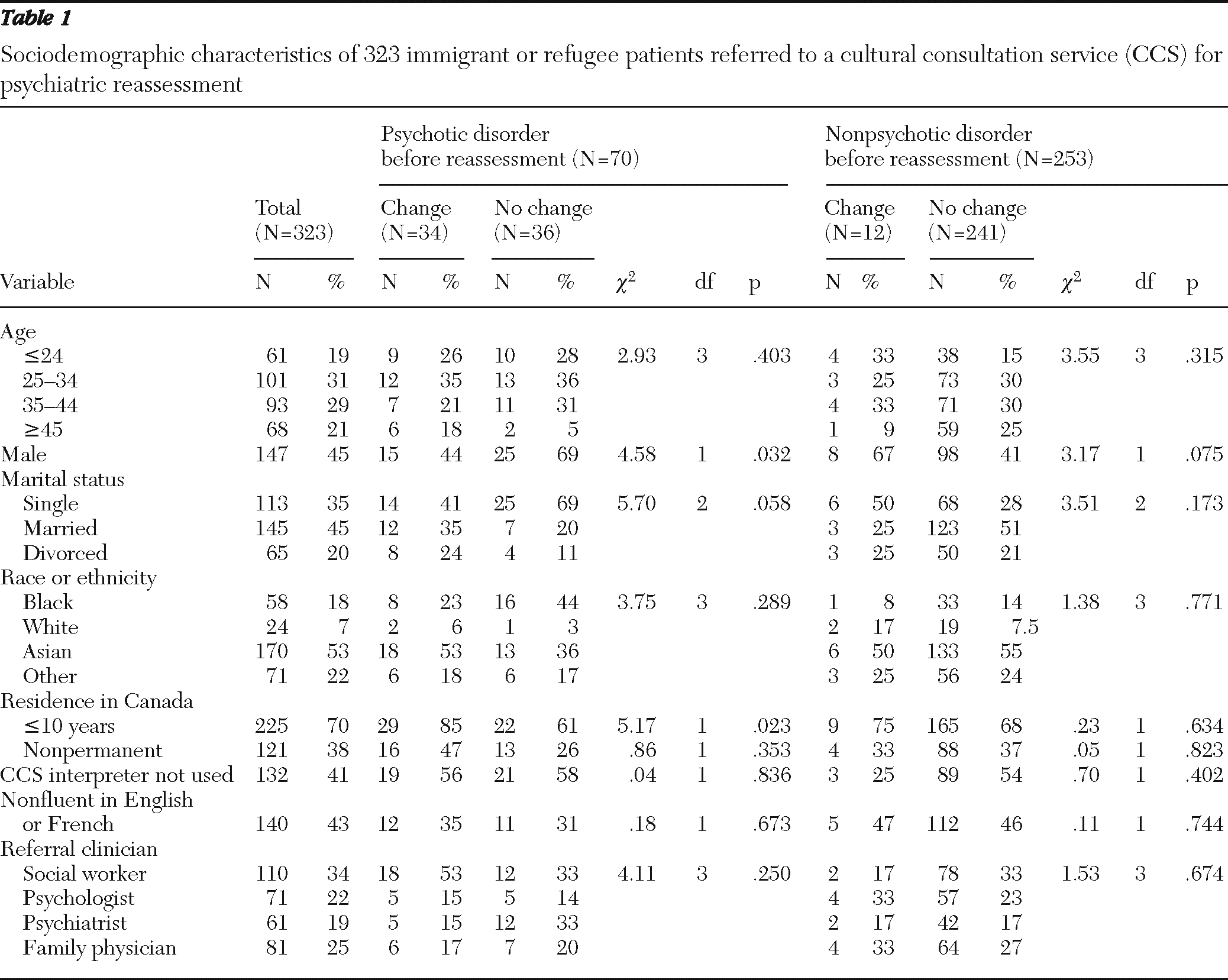

The CCS conducted 358 patient consultations, of which 35 (11%) were excluded from the study sample, including 20 patients <16 years of age, one patient whose age was not recorded, ten patients with missing evaluation data, two family referrals with no identified patient, and two family referrals where a child was the identified patient. Thus 323 (90%) cases were included in analyses (

Table 1). Mean±SD age was 36.0±12.9 years, and mean length of residence in Canada was 7.8±9.4 years. By race-ethnicity, 18% of the sample was black, 7% white, 5% (N=17) Canadian First Nations, 7% (N=24) Hispanic, 9% (N=30) Middle Eastern or North African, 40% (N=130) South Asian, and 13% (N=40) Southeast Asian or East Asian. The black group included 41 (71%) patients from sub-Saharan Africa and 17 (29%) patients from the Caribbean.

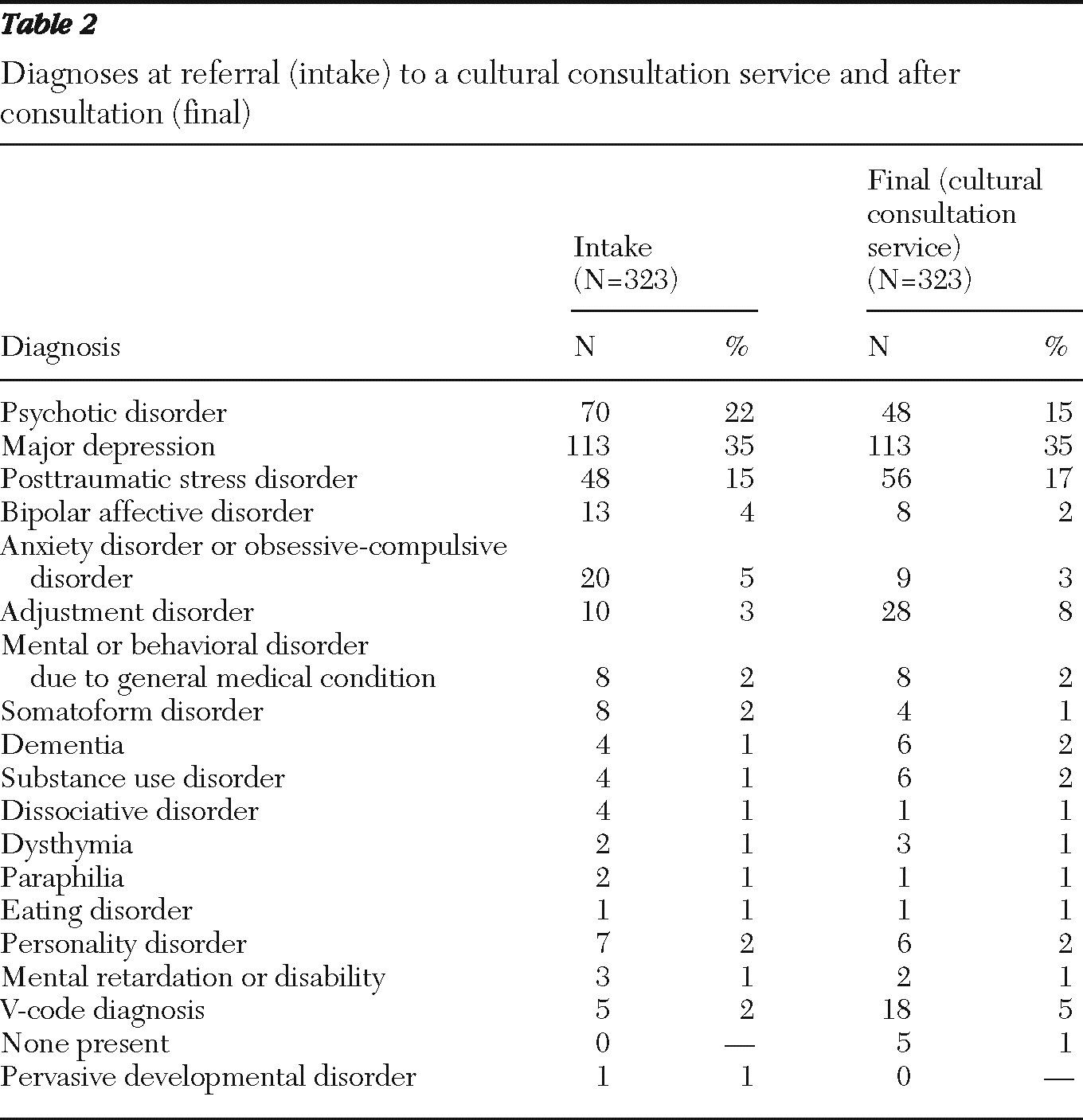

Intake (referral) and final (CCS) diagnoses

Overall, 22% had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder at intake, including psychosis NOS (N=37, 53%), schizophrenia (N=26, 37%), schizoaffective disorder (N=3, 4%), brief psychotic disorder (N=2, 3%), and delusional disorder (N=2, 3%). Diagnoses of the 253 patients in the nonpsychotic disorder group are shown in

Table 2.

After the CCS consultation, 15% of patients were diagnosed as having a psychotic disorder and 85% as having a nonpsychotic disorder. Psychotic disorder diagnoses included schizophrenia (N=25, 52%), psychosis NOS (N=14, 29%), delusional disorder (N=4, 8%), schizoaffective disorder (N=4, 8%), and schizophreniform disorder (N=1, 2%). Final diagnoses of nonpsychotic disorders are shown in

Table 2.

Patterns of rediagnoses

For 34 of 70 (49%) patients, psychotic disorders diagnosed at intake were converted to nonpsychotic disorders after CCS assessment. On the other hand, of 253 patients with an intake diagnosis of a nonpsychotic disorder, only 12 (5%) patients received a final diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. This difference was statistically significant (p<.001). [An appendix summarizing the specific change in diagnosis for each rediagnosed case is available as an online supplement to this article at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Change to nonpsychotic disorder.

Of the 34 patients, 26 (76%) had an initial diagnosis of psychosis NOS, four (12%) had schizophrenia, two (6%) schizoaffective disorder, and one (3%) each had brief psychotic disorder and delusional disorder. After CCS assessment, 13 of these patients (38%) were diagnosed as having major depression (of which four diagnoses were major depression with psychotic features), seven (20%) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), five (15%) adjustment disorder, three (9%) bipolar affective disorder, and one (3%) each with personality disorder, dementia, eating disorder, and seizure disorder. In two cases (6%), the diagnosis was no psychiatric disorder.

Change to psychotic disorder.

Of the 12 patients whose diagnosis switched from a nonpsychotic disorder at intake to a psychotic disorder after CCS assessment, five (42%) had an initial diagnosis of major depression (of which three were major depression with psychotic features), two (17%) PTSD, two (17%) bipolar affective disorder, two (17%) anxiety disorder, and one (8%) adjustment disorder. After assessment by the CCS, five (42%) were rediagnosed as having psychosis NOS, four (34%) as delusional disorder, and one (8%) each as schizophrenia, schizophreniform, and schizoaffective disorder.

Factors associated with change in diagnosis to nonpsychotic disorder

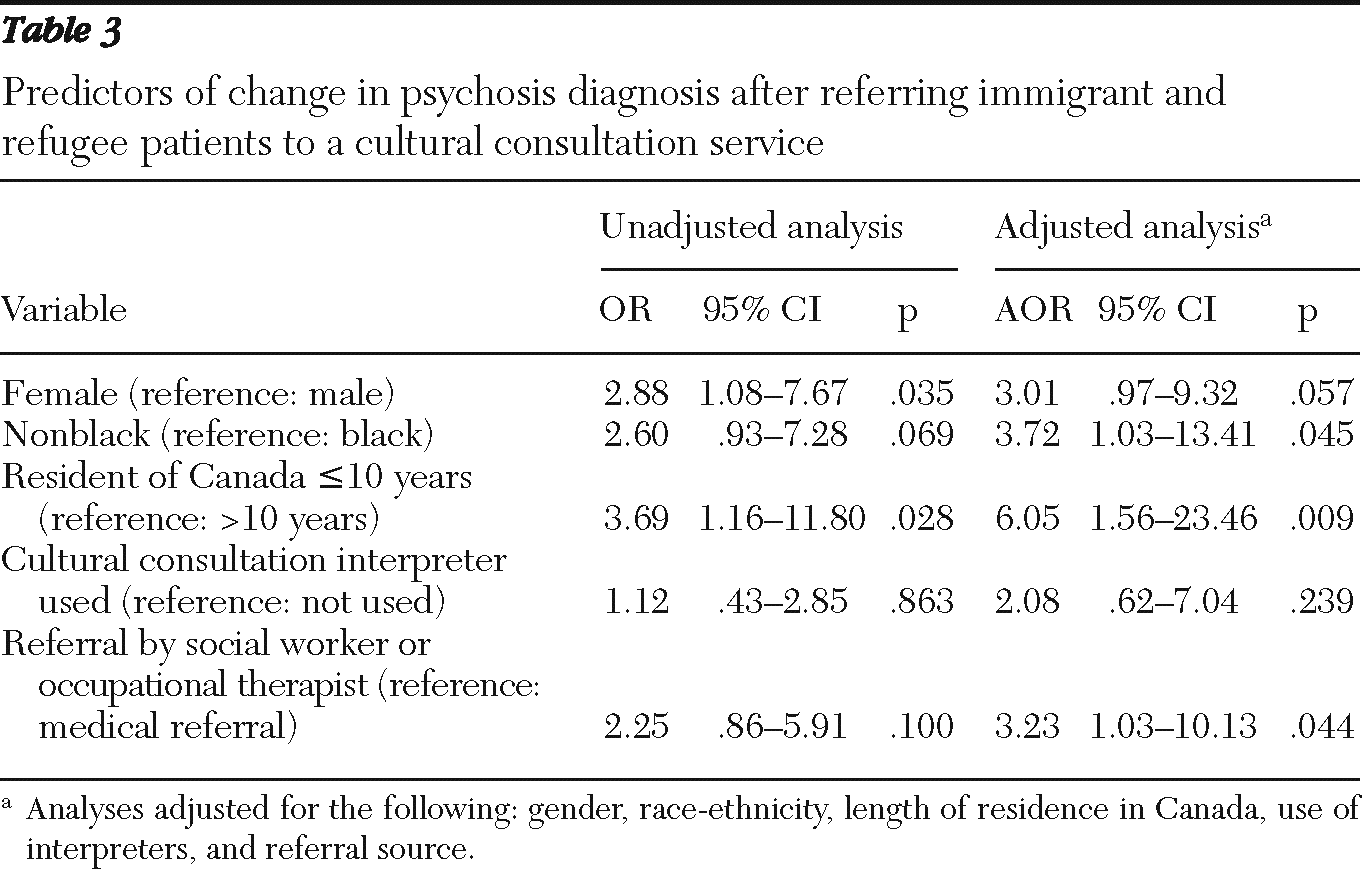

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted only for the 70 patients with an intake diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. Because a change from nonpsychosis at intake to psychosis at final occurred in only 12 cases, multivariate analyses could not be conducted for this group. As shown in

Table 3, on an unadjusted basis, change in diagnosis from psychosis to nonpsychosis was significantly more likely for female patients (odds ratio [OR]=2.88) and patients residing in Canada ten years or fewer (OR=3.69). In the multivariate model, patients in Canada ten years or fewer (OR=6.05), patients who were not black (OR=3.72), and patients who came to the CCS via nonmedical referral routes (social work or occupational therapy) (OR=3.23) were significantly more likely to receive a diagnosis that differed from the diagnosis at intake. The final model had good discriminative power (c index=.77, 95% confidence interval=.66–.88) and calibration (p=.989 for the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic).

Discussion

Overdiagnosis of psychosis was frequent in this sample. For 70 patients referred to the CCS with an initial diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, use of the DSM-IV cultural formulation for case reassessment resulted in 34 (49%) patients' illnesses being rediagnosed as nonpsychotic disorders. Of 253 patients with initial diagnoses of nonpsychotic disorders, on the other hand, 12 (5%) were rediagnosed as having psychotic disorders. Major depression, PTSD, adjustment disorder, and bipolar affective disorder were the most common new diagnoses on reassessment. Logistic regression analyses found that change after cultural consultation from an initial psychotic disorder diagnosis to a rediagnosis of a nonpsychotic disorder was significantly associated with more recent arrival in Canada, being in a racial-ethnic group other than black, and being referred to the CCS via nonmedical service routes.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to undertake comparison of psychiatric diagnoses recorded by clinicians in standard care with diagnoses made on reassessment of the cases through cultural consultation, which uses the cultural formulation, interpreters, and culture brokers. Previous studies that have examined potential cultural biases in diagnostic assessment have used interventions that aimed to mitigate the influence of culture on clinician assessments as a way to increase the validity and reliability of diagnosis (

8,

37,

38). Broadly, these interventions entailed either applying strict diagnostic criteria to retrospectively reassign diagnoses (

39,

40) or using semistructured interviews to generate diagnoses for comparison with routine diagnoses made by clinicians (

41,

42).

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that found that case reformulation using strict diagnostic criteria and semistructured interviews often results in significant changes to diagnoses made in routine clinical settings (

41–

43). In addition, the diagnostic changes found in our study occurred in the directions expected from the literature, with overdiagnosis of psychotic disorders more frequent than underdiagnosis (

8). It is not clear to what extent the changes resulted from following diagnostic criteria more stringently, from conducting more systematic or complete assessment, or from obtaining specific information about culture and social context through use of the cultural formulation and collaboration with interpreters and culture brokers.

Although the literature has largely centered on clinicians' difficulty in distinguishing schizophrenia and affective disorders (

41,

43), we found that for patients with an initial diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, case reassessment with the cultural formulation led to a range of diagnoses, including major depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and adjustment disorder. Of the 323 patients in our sample, 56 (17%) received a final diagnosis of PTSD, and of the 56, eight (14%) cases of PTSD had been missed by the referring clinicians (

Table 2). Fully 20% of those who had a change from an intake diagnosis of a psychotic disorder to a CCS diagnosis of a nonpsychotic disorder were diagnosed as having PTSD. A third of our study sample consisted of refugees, many from South Asia, which likely explains the prevalence of PTSD and adjustment disorders. Clinical reports have highlighted how clinicians may mistake PTSD for psychosis in refugee populations and how attention to cultural factors can improve diagnostic accuracy (

44,

45).

The finding that rediagnosis was more likely among patients who were more recent arrivals in Canada may reflect biases in the referral sample or characteristics of new immigrants related to their migration history, including shorter duration of psychotic symptoms associated with less stability in the clinical picture; shorter duration of contact with the Canadian health care system, with less opportunity to collect clinical information, resulting in less certainty in the referral diagnosis; and greater cultural differences in newcomers' style of clinical presentation compared with patients more familiar with the Canadian context. More precise study of health care contacts and diagnostic assessments prior to CCS referral could provide evidence for these complementary explanations.

Our finding that overdiagnosis of psychotic disorders was significantly more likely among persons who were not black is surprising, given that the literature suggests greater likelihood of misdiagnosis of blacks (

2,

8). However, diagnostic biases before the CCS consultation in our study may differ from those identified in previous studies because the black patients in our sample were recent immigrants or refugees from Africa or the Caribbean, whereas black samples included in most studies from the United States include more indigenous black populations and fewer immigrants. The finding of lower rates of misdiagnosis of psychosis among blacks may reflect unknown diagnostic and referral biases. The lower rate of CCS reassessment of psychotic disorders among black patients compared with other ethnocultural groups may have occurred because black patients with a definite psychotic disorder were more likely than nonblack patients to be referred to the CCS for reasons other than diagnostic uncertainty (such as nonadherence to treatment). Alternatively, referring clinicians may have been more alert to the potential for misdiagnosis of psychotic disorders with black patients and made the diagnosis of psychosis only when they had a high level of certainty. However, in the absence of information on community rates, diagnostic practices, and referral patterns, these alternative explanations remain conjectures requiring further research.

Our finding that overdiagnosis of psychotic disorders was significantly more likely for persons who came to the CCS via nonmedical referral routes aligns with literature that links misdiagnosis to greater numbers of patients from racial-ethnic minority groups entering psychiatric care through nonmedical and social services than through family physicians (

13). Further research on diagnostic practices and referral patterns in the community is needed to better understand these results.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that misdiagnosis of psychotic disorders occurs with immigrant and refugee patients from all racial-ethnic backgrounds. Although we cannot estimate the frequency of misdiagnosis in other health care settings, the rates we identified may be lower limits, given the fact that only clinicians alert to the potential for cultural issues are likely to refer cases to our service. In this referral sample of mainly immigrants and refugees—many from South Asia—PTSD and adjustment disorder were frequently misidentified as psychosis.

The study had important limitations. It examined a sample referred to a single specialized service, and this may have introduced unknown biases. The study involved retrospective analysis of data collected primarily for clinical purposes, and in some instances the absence of data may reflect inconsistencies in data collection or recording rather than true differences between cases. There is no “gold standard” in cross-cultural assessments, so CCS diagnoses are not necessarily better than those made by referring clinicians. We did not assess what impact the time gap between the referral and the final CCS diagnosis might have had on diagnosis or what role any antipsychotic medication administered after the time of referral diagnosis may have had in subsequent diagnosis. However, it is important to point out that the CCS diagnostic assessment considers these factors so they are unlikely to account for any reduction in the diagnosis of psychosis. There was no longitudinal follow-up of patients, so the stability of CCS diagnoses remains unknown.

Although our findings suggest the clinical usefulness of the cultural formulation for improving diagnostic accuracy, the precise aspects of cultural consultation that contribute to this outcome are unknown. We are unable to determine the extent to which study findings can be differentially attributed to use of the

DSM-IV cultural formulation or to the cultural expertise (brokers and consultants) available at the CCS. Thus there is a need for studies that compare clinical outcomes of the use of cultural consultation with outcomes from other strategies to enhance cultural competence and accuracy in diagnostic assessment (

25). The findings of this study suggest that cultural consultation using an expanded version of the

DSM-IV-TR cultural formulation can identify probable misdiagnoses of psychoses. The results highlight the clinical utility of the cultural formulation and provide further justification for efforts to develop an expanded version of the outline and a corresponding cultural formulation interview for

DSM-5. Qualitative aspects of our study of implementation of the cultural formulation, including assessment of clinician styles of reasoning and heuristics used in resolving uncertainty of psychotic disorder diagnosis, will be the focus of a subsequent report.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.