Although excessive alcohol consumption is the third leading cause of preventable death in the United States (

1), only 11% of the 17.9 million Americans with an alcohol use disorder will receive treatment during any given year (

2). Those who do will receive care, on average, 20 years after the onset of heavy drinking (

3). Thus there is a need for earlier intervention with the vast number of heavy drinkers in the general population, who are at risk for severe alcohol problems, morbidity, and mortality.

Both the lack of perceived need for treatment and the critical shortage of treatment slots are driving the current thrust of federal health policy to expand alcohol treatment beyond specialized settings and into mainstream medical care, particularly primary care (

8–

10). Backed by extensive data supporting the efficacy of primary care–based alcohol screening and brief intervention (

11–

15), the authors of the 2009 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (H.R. 3590) included provisions to integrate evidence-based alcohol intervention within patient-centered medical homes. In addition, the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (H.R. 6983) requires that health plans provide benefit levels for alcohol treatment services that are commensurate with coverage for other medical services (

16,

17). Further, private insurers, Medicaid, and Medicare have developed billing codes that reimburse primary care providers for delivering alcohol interventions (

18,

19).

Although these efforts hold promise for reducing the alcohol-related health burden in the overall population, they also raise a question about their impact on existing disparities in alcohol problems. With the exception of some Asian-American subgroups, in the United States racial-ethnic minorities are at greater risk of alcohol dependence symptoms, negative drinking consequences, and alcohol-related morbidity and mortality compared with whites (

20–

23). This might partly reflect racial disparities in access to and utilization of treatment for substance use disorders, but evidence of such disparities is modest, and even mixed (

24–

28).

There may be several reasons for the lack of significant treatment disparities. Individuals from racial-ethnic minority groups are more likely than whites to be mandated to addiction treatment by the criminal justice system, and this can have the effect of reducing disparities in treatment use (

29,

30). Another reason may be that treatment studies tend to focus only on the tip of the iceberg—people with severe and diagnosable alcohol problems, who are likely to experience serious personal troubles because of their drinking and to be pressured by spouses or partners, family, and friends to seek help. Both alcohol problem severity and social pressure can be strong motivators of treatment seeking (

31,

32), especially, perhaps, for racial-ethnic minorities, who are more likely to experience tangible consequences because of their drinking. Finally, health insurance coverage appears to play a lesser role in determining use of addiction treatment than use of other health-related services, possibly because specialty treatment is largely subsidized by public funding (

33,

34).

Nevertheless, mechanisms that increase access to and use of specialized treatment by racial-ethnic minority groups might not apply to the use of alcohol services in medical settings. Indeed, minorities may be less likely to access evidence-based treatment in primary care because of a lack of health insurance (

35). Also, because alcohol screening and brief intervention in general medical settings is largely intended to prevent severe alcohol problems among at-risk and nondependent drinkers (

8), legal coercion and social pressuring to receive these interventions seem less likely to occur.

Methods

This analysis used data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative, longitudinal survey of U.S. adults residing in household and noninstitutional group quarters. Wave 1 data were collected from 43,093 respondents in 2001–2002, and Wave 2 data were collected from 34,653 respondents in 2004–2005, with a follow-up rate of 86.7% and a mean interval of roughly three years (36.6 months) between the two waves. The survey was administered through face-to-face, computer-assisted interviews. Approximately 16% of Hispanic respondents were interviewed in Spanish (

37). Additional information on the study’s design is provided by Grant and colleagues (

38).

This study analyzed data from the subset of Wave 1 respondents who met criteria for at-risk drinking or alcohol abuse in 2001–2002 (N=9,116), including a large majority (N=7,494, 82%) who were re-interviewed three years later at Wave 2. Alcohol-dependent drinkers were excluded because the policy that is the subject of this study—expanding treatment services by instituting alcohol screening and intervention in primary care—is not well-suited to treating dependent drinkers (

8,

39). Given our concern with potential disparities in access to high-quality alcohol services, the analysis was restricted to nondependent drinkers for whom these interventions have demonstrated effectiveness. The prospective, longitudinal design is an improvement over the more common approach of assessing lifetime treatment utilization, a method that precludes assessment of temporal ordering and can mask long delays in obtaining treatment.

Following guidelines of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), at-risk drinkers were defined as men who consumed more than four drinks in a day or more than 14 drinks in a week and women who consumed more than three drinks in a day or more than seven drinks in a week during the 12 months prior to baseline (

8). Alcohol abuse was defined as the presence of at least one of four diagnostic criteria during the 12 months prior to baseline, including hazardous alcohol use, social problems, legal problems, or failure to fulfill important roles due to one’s drinking (

40), and was assessed by using NIAAA’s Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV).

Measures

The key outcome was receipt of an alcohol intervention during the 12 months prior to baseline or at any time during the three-year follow-up period between baseline and Wave 2. Our outcome measure was informed by NIAAA guidelines that are designed to promote best practices in screening, brief intervention, and referral to specialty treatment for people who are at-risk drinkers or have an alcohol use disorder (

8). An alcohol intervention was defined as alcohol-related services provided by a physician or mental health clinician (doctor, psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker) or a specialty treatment program (detoxification, outpatient, inpatient, rehabilitation facility, or therapeutic community or halfway house), the two recommended sources of alcohol treatment services. Alcohol-related services received in alternative settings (Alcoholics Anonymous, family services or social service agency, emergency department, crisis center, or employee assistance program) and from clergy were also examined in separate analyses.

Racial-ethnic group was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, foreign-born Hispanic, U.S.-born Hispanic, Asian American/Pacific Islander, and Native American. Because of limited numbers of respondents in some minority groups, racial-ethnic minorities were pooled for multivariate analyses. Selection of baseline covariates was informed by the extant literature and by preliminary analyses indicating significant, bivariate associations between minority status, the key outcome, or both. Final models adjusted for sex, age, education, income, health insurance, any prior lifetime alcohol intervention, and severity of need for alcohol intervention, including frequency of heavy drinking (defined as ≥5 drinks and ≥4 drinks in a day for men and women, respectively) and negative consequences of drinking (interpersonal, legal, and role-related problems).

Analysis

Differences in demographic characteristics and severity of need at Wave 1 among racial-ethnic groups were assessed by using chi square tests and t tests. To assess racial disparities in the receipt of an alcohol intervention, prospective analyses were conducted by using logistic regression models and adjusting for covariates. To assess whether expanding alcohol interventions into alternative service venues could potentially reduce racial disparities, logistic regression was used to estimate racial differences in services received from an expanded array of settings, including federally recommended clinical providers and specialty settings, as well as nonmedical providers where study participants reported receiving alcohol counseling. STATA, version 10, was used in all analyses to account for the complex survey design (

41).

Results

The characteristics of the sample are shown in

Table 1. Members of racial-ethnic minority groups constituted 23% of the overall sample, with African Americans representing roughly one-third of the minority sample, and U.S.-born and immigrant Hispanics each representing one-fourth. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Native Americans each made up an additional 9%. Compared with whites, members of minority groups were more likely to be male, younger, of lower socioeconomic status (less education and lower incomes), and without health insurance. Minority respondents were also more likely than whites to drink heavily on a weekly basis or more often and were two times more likely to experience negative drinking consequences.

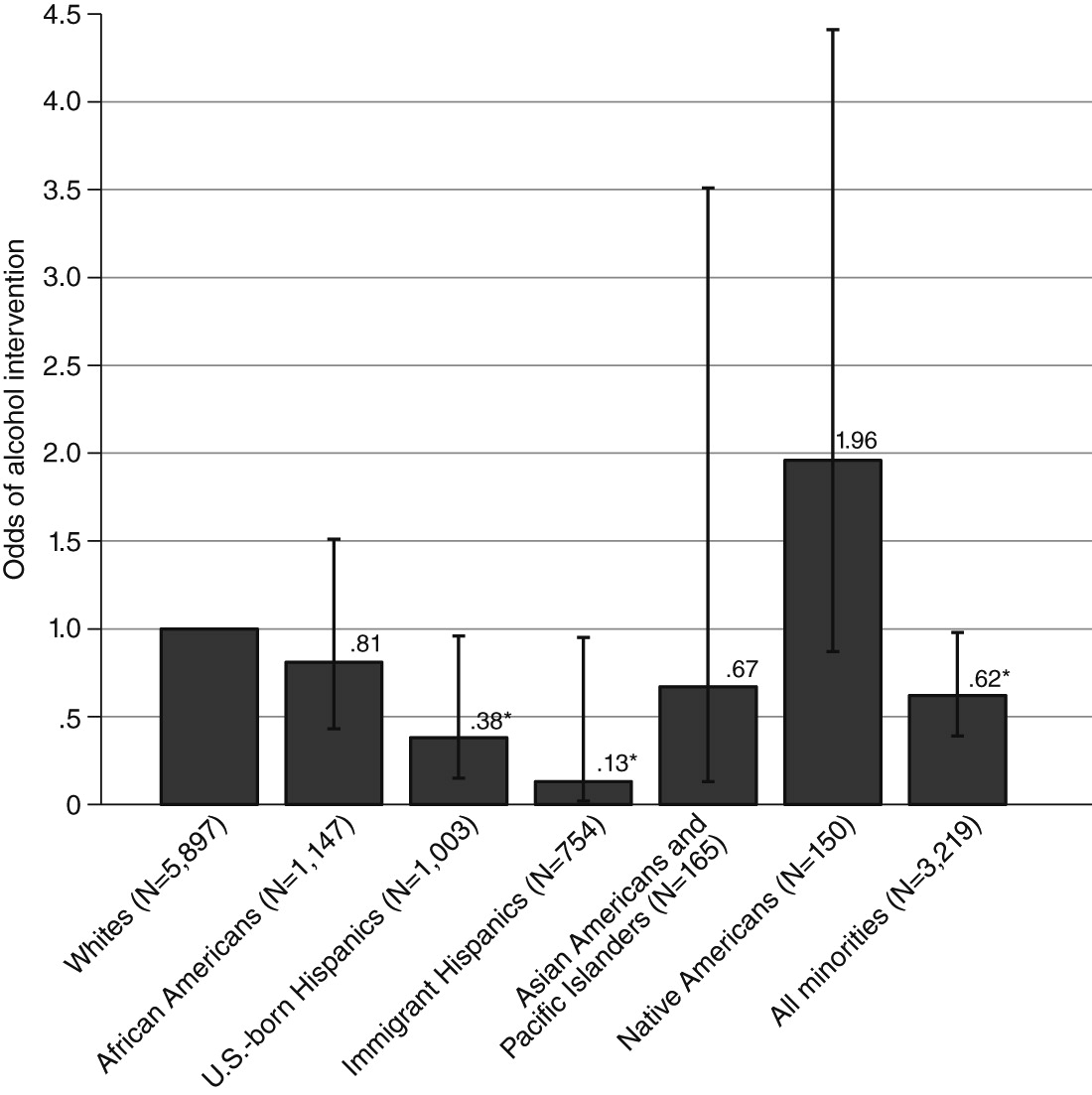

Despite indications of greater need for alcohol services, as a group racial-ethnic minorities were less likely than whites to have received an alcohol intervention during the study period (

Table 1). They also had two-thirds lower odds of receiving care (odds ratio [OR]=.62, p<.05) (

Figure 1). Both African Americans and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders had lower odds of receiving care relative to whites, although these results were not statistically significant. There were striking disparities between Hispanics and whites in the odds of receiving care (OR=.38, U.S.-born Hispanics, and OR=.13, foreign-born Hispanics, p<.05). By contrast, Native Americans had nearly two times the odds of receiving an alcohol intervention compared with whites, but this was nonsignificant because of the small number of Native Americans.

As

Table 2 shows, after the analyses were adjusted for demographic characteristics and drinking-related variables, differences were found between minority groups and whites in the odds of receiving an alcohol intervention. In all cases, the disparity between minorities and whites not only persisted but increased after we took into account group differences in demographic characteristics, severity of need for treatment, and prior treatment history (p<.01 for all).

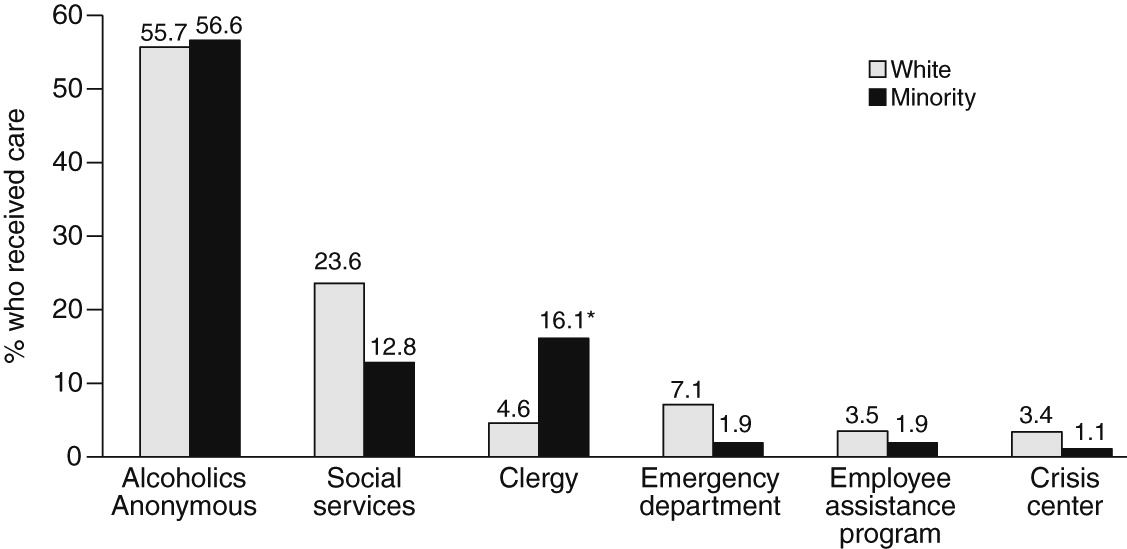

Given these disparities in services utilization, an important question for policy makers is whether evidence-based alcohol interventions should be extended beyond primary care into alternative settings and whether doing so might help to reduce these disparities.

Figure 2 shows the percentage of minorities and whites who received alcohol counseling from an alternative provider. Not surprisingly, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) was by far the most commonly reported venue among white and minority drinkers. But because AA serves persons with severe alcohol problems who are already trying to become clean and sober, it is more appropriate as a complement to primary care–based intervention and specialty treatment rather than as an alternative site for screening and brief intervention (

8,

42). Social service programs and clergy were the next most common sources of alcohol counseling. Members of racial-ethnic minority groups were nearly four times more likely than whites to receive alcohol counseling from clergy (p<.05). In addition, about 1%−2% of minorities and 3%−7% of whites received counseling from each of the following three sources: emergency departments, employee assistance programs, and crisis centers.

Table 3 presents the results of our analysis simulating the effects of expanding evidence-based alcohol intervention into alternative settings other than AA. Although for most groups the estimated disparity in the receipt of an alcohol intervention changed very little, the disparity between U.S.-born Hispanics and whites shrank by 39% after the expansion (OR=.38 before versus OR=.53 after the expansion), and the difference between the two groups in the odds of obtaining care was no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study we considered how widespread provision of evidence-based alcohol intervention in medical settings, especially primary care, might affect racial-ethnic disparities in access to high-quality alcohol services. The results showed that over the four-year study period, racial-ethnic minorities as a group had roughly half the odds compared with whites of receiving an alcohol intervention from primary care providers or specialty treatment programs. This suggests that federal efforts to promote routine alcohol screening and intervention in primary care might not benefit racial-ethnic groups equally. Indeed, such efforts could have the unintended consequence of increasing disparities in access to high-quality treatment and, ultimately, exacerbating disparities in alcohol problems.

The most striking disparities in the receipt of an alcohol intervention were between whites and U.S- and foreign-born Hispanics. This finding is consistent with the results of our previous study, which was based on the U.S. National Alcohol Survey, indicating that among at-risk and problem drinkers, Hispanics were far less likely than whites to obtain primary care (

36). Notably, compared with other racial-ethnic groups, Hispanics have some of the highest rates of heavy drinking and alcohol dependence and have low rates of dependence remission (

43–

46). Therefore, it is important to ensure that Hispanics are provided access to high-quality, early intervention. This is especially true for U.S.-born Hispanics, whose rates of alcohol disorder significantly exceed those of immigrant Hispanics (

37,

47,

48).

Although most efforts to expand alcohol services have focused on primary care settings, there is growing interest in a wider range of venues, ranging from hospital emergency departments and hospital wards to the criminal justice system and college settings (

49). Our study results highlight the need to consider still other settings. Specifically, when our simulation analysis redefined the study outcome as the receipt of an alcohol intervention in primary care, specialty treatment, or nonmedical service setting, the disparity between U.S.-born Hispanics and whites was reduced and was no longer statistically significant.

Special consideration should be given to the role that social and family service agencies and clergy or faith-based organizations might play in promoting, linking, and providing evidence-based alcohol interventions to minority communities, given that these entities were common sources of alcohol counseling among minorities. Faith-based organizations have a long history of serving disadvantaged communities (

50,

51), and churches have become increasingly involved in health promotion and intervention in African-American and Latino communities (

52). The commitment of faith-based institutions to improving the welfare of their communities, and the trust and respect felt toward these institutions (

53), may be critical to linking underserved minority populations with high-quality alcohol interventions.

Reaching Hispanic immigrants might require special efforts in light of the formidable barriers they face, including lack of health insurance, fear of mistreatment and deportation, limited English proficiency, and logistical issues related to transportation and child care (

54–

58). Some health and social service agencies have successfully partnered with local bicultural and bilingual organizations to engage Hispanic immigrants in programs that address mental and general medical health. The success of these partnerships has been achieved partly through community building, enrichment, and social support activities that appeal to broader individual and family interests (

59). Of note, the involvement of

promotoras de salud—volunteers or paid lay health workers who are trusted members of the community or who have an unusually close understanding of the community served—has been vital to efforts to increase services utilization by Hispanic communities.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the very low rates of treatment utilization during the study period, combined with relatively small samples of racial-ethnic minority subgroups, required that we pool minority groups in multivariate analyses. Such sample size issues are common in research focused on racial disparities in treatment utilization and often are the reason that these types of analyses tend to focus on lifetime treatment use. However, analyses of lifetime treatment are associated with a different set of limitations, as noted above.

Another limitation of the study was the lack of data on the respondents’ primary language and language of interview, which precluded analysis of disparities among Hispanics by language. Spanish-speaking Hispanics are far less likely than English-speaking Hispanics to access health care services generally (

60). Notably, a recent study found that among Hispanics, a preference for speaking Spanish and for socializing with other Hispanics predicted lower use of mental health services but was unrelated to alcohol or drug treatment utilization (

61).

Third, the NESARC does not distinguish among primary care providers—in particular community health centers, which are a key source of health care for low-income and uninsured and underinsured racial-ethnic minorities (

62). To the extent that evidence-based alcohol screening and intervention are integrated into routine care at community health clinics, these settings hold promise for mitigating disparities in treatment access and quality. Funding provided to federally qualified community health centers through the ACA might be instrumental in this regard (

63). Further, increased insurance coverage under the ACA might also reduce disparities in access to medically based alcohol intervention. Yet this might depend on the presence of community health centers and their implementation of high-quality alcohol interventions. Even among persons with health insurance, in the absence of a neighborhood health clinic, racial disparities in the use of substance use treatment and other mental health services have been significant (

64).

Finally, as noted above, this analysis included persons with diagnosable alcohol abuse but excluded those with alcohol dependence, given that primary care–based alcohol intervention appears to be less effective for the latter group. With the change to the DSM-5, alcohol abuse and dependence are no longer distinguished. Thus it is unclear how our study findings will be interpreted in light of the new diagnostic guidelines. But if lower utilization of alcohol treatment by minority groups is fundamentally related to logistical, attitudinal, and social barriers to primary care, it seems likely that racial disparities will persist.