The concept of personal recovery informs the goals of treatment, rehabilitation, and support services for individuals with psychiatric illness (

1–

3). It also reflects a historic shift from a focus on symptom reduction to wider considerations of individual well-being consonant with the World Health Organization’s landmark definition of health (

4). Overemphasis on symptom reduction risks neglecting dimensions of personal recovery such as hope, empowerment, and life satisfaction (

3,

5). From a policy perspective, the concept of personal recovery has been applied to national efforts to improve mental health care, including peer-provided services, psychiatric advance directives, illness management programs, and supportive housing (

6). The notion of personal recovery is also embedded in the language of the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansions (

7,

8) and has been incorporated into the movement toward patient-centered care (

9).

While a plurality of studies have found positive associations between personal recovery and clinical markers of improvement, others have found less concordance. For example, in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Van Eck and colleagues (

10) concluded that positive, negative, and affective symptoms of schizophrenia were modestly but significantly correlated with both hope and empowerment. They also observed high heterogeneity in relationships between symptoms and recovery among studies; in six of 20 studies reviewed, they found no relationship or an association in the opposite direction from expectations. Rossi and colleagues (

11) performed a cluster analysis to examine these specific relationships at the individual level and identified typologies in which features of personal and clinical recovery were unrelated. Similar findings have been obtained among individuals coping with depression, anxiety, and psychosis (

12,

13). The evidence indicates that markers of clinical recovery are inconsistently related to markers of personal recovery and that patients could therefore benefit from an increased focus on personal recovery in treatment (

14). This view, in turn, has driven researchers to begin developing treatments to explicitly promote personal recovery alongside clinical recovery (

15–

17) and to identify and track features of treatment, such as the provider-patient relationship, that may play a critical role in facilitating personal recovery (

18,

19).

Research on the relationship between treatment and personal recovery has been limited in two respects. First, studies generally draw from nonrepresentative populations (

10), investigating outcomes in clinical research settings that fail to reflect the realities of health care delivery in lower-resourced communities (

15). Second, the vantage point for analysis omits comparisons between individuals who receive mental health care and those who do not, leaving unresolved the relationship between personal recovery and treatment itself. This demographic is considerable: roughly 25% of adults in the United States with moderate-to-severe psychological distress have not received treatment in the past year (

20).

We examined the relationship between treatment (versus nontreatment) and personal recovery in a representative sample of adults in California with mild/moderate-to-serious psychological distress (

21). Specifically, we examined five dimensions of personal recovery: life satisfaction, hope, connectedness, empowerment, and internalized stigma. Among those who received treatment in the past year, we further examined relationships between personal recovery and treatment completion, provider specialty, and intensity of care (

22).

Discussion

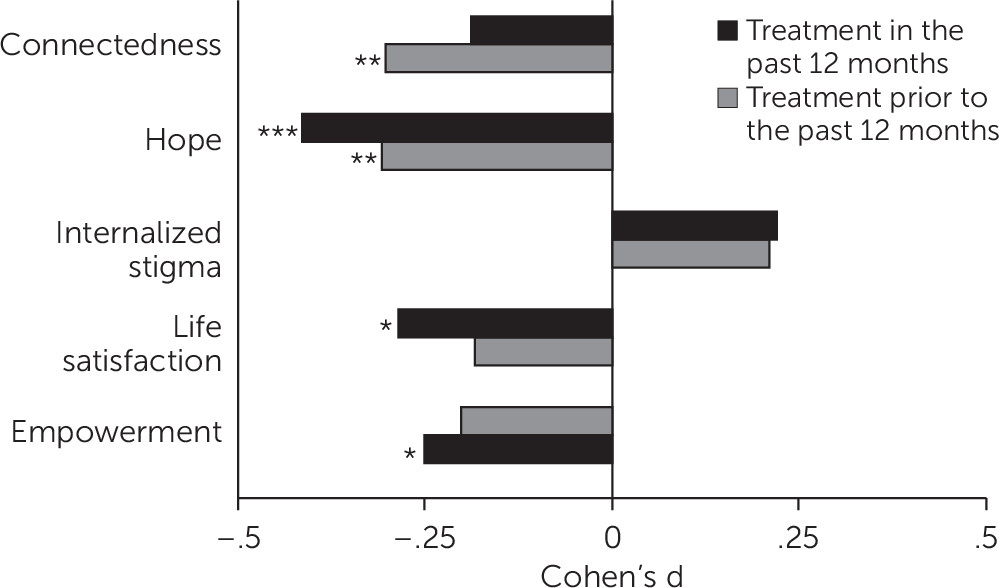

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between receipt of mental health services and personal recovery in a large, population-based sample. Among adults in California reporting mild/moderate-to-serious psychological distress, only 41% of individuals reported receiving outpatient mental health care in the past 12 months—comparable to prior research (

47). Of those, 40% sought care from only a general medical provider. This finding is substantially different from samples in prior studies on personal recovery, which examined only individuals who received care, typically from mental health specialists and in the recent past. Against this backdrop, we found that receipt of outpatient mental health services was associated with lower levels of self-reported personal recovery on four of the five dimensions studied, even after adjusting for differences in psychological distress. Individuals who received mental health services endorsed lower personal recovery scores in the dimensions of hope, empowerment, life satisfaction, and connectedness compared with those who never received treatment. Previous investigations on this topic have focused on narrowly defined patient populations, such as individuals receiving treatment for schizophrenia. Associations between symptom reduction and personal recovery in such populations have been wide ranging (

10,

48,

49).

One explanation for this discrepancy is that past research has focused on clinical care in which treatment efficacy and fidelity to protocols are closely monitored. We found that, among individuals who reported completion of treatment, outcomes were more favorable, particularly with regard to empowerment and hope, two concepts that have elsewhere been associated with recovery-oriented treatment (

50). However, their outcomes were still worse than those who went untreated, and individuals who completed treatment were a minority in the sample (22%, N=132), underscoring the fact that, at the population level, high quality and consistency of care are not guaranteed.

Relationships varied across specific personal recovery dimensions. For people receiving treatment more than 12 months prior to the survey, treatment was associated with less empowerment and less connectedness than nontreatment. Recent treatment had no statistically significant association with these outcomes but was associated with lower levels of life satisfaction compared with levels among those never treated. Recent—and in many cases, ongoing—engagement in therapy may make it difficult for individuals to endorse this construct, measured with statements such as, “In most ways my life is close to ideal.” The construct of hope appeared to be the dimension of personal recovery most robustly related to treatment, showing negative associations with both past-year and less recent treatment; hope also represented the strongest associations of all the recovery dimensions. Past research has identified hope as “central to personal recovery” and as a foundational motivator leading to other aspects of personal recovery, such as identity, meaning, and personal responsibility (

14,

51). Thus, this finding is of particular importance.

Second, we found that self-reported completion of treatment was associated with higher levels of empowerment and lower levels of stigma compared with leaving care prior to completion. These findings are consistent with the notion that internalized stigma may be a motivating factor in leaving treatment (

52,

53) and that stigma tends to persist over time (

54). Previous research indicates that iatrogenic effects of therapeutic interventions are predicted by heightened internalized stigma and lack of social support (

55). Additionally, individuals who did not find treatment useful may have opted to discontinue, a rational choice, but one that underscores the need for improved treatment.

We did not identify any significant pattern of relationships between provider type, such as mental health specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, licensed social worker), and personal recovery outcomes or between minimally adequate care and personal recovery. Given the small subsample we examined to inspect these relationships (N=132) compared with the larger sample for all other analyses, we were underpowered to detect effects. Additional rounds of the CWBS may enable the study of these relationships in further detail.

Our cross-sectional design cannot determine whether relationships are causal. For two reasons, we find that observed results are unlikely to be driven by individuals with greater psychological distress self-selecting into mental health care. First, analyses were adjusted for level of psychological distress to directly account for this possibility. Second, we did not find that receipt of care from a mental health specialist was associated with lower personal recovery scores compared with generalist care. Past evidence indicates that individuals with more-severe symptoms are more likely to seek care from a mental health specialist (

56). Thus, if individuals with greater psychological distress were in fact self-selecting into specialty care, lower personal recovery levels among those seeing mental health specialists would be expected. We did not find this association.

Collectively, the pattern of results suggests that negative associations between mental health treatment and dimensions of personal recovery may in part reflect poor care retention or indicate barriers to access. Among those who completed treatment in the past 12 months, a significant number received services from a general medical provider (40%) rather than a trained mental health specialist. This finding is consistent with studies indicating a shortage of mental health specialists in parts of California (

57), which reflects U.S. national trends (

58). Likewise, data suggest that those with greater mental health needs often have poorer access to care, including financial and logistical barriers that may have undermined these individuals’ ability to remain in care until completion (

59–

61).

This study had several limitations. First, the data represent pooled cross-sectional estimates; as such, causality cannot be inferred, and there remains the possibility of omitted variable bias as well as the possibility that those with lower personal recovery, independent of symptom severity, self-selected into care. To more fully explore the relationship between mental health treatment and personal recovery, longitudinal studies are needed. Second, the data set does not include clinical diagnoses. Our intention was to expand the research focus to encompass individuals who had not received treatment and therefore were unlikely to have received a formal diagnosis. Third, all study measures relied on self-reporting. Those who did not respond to the survey may have differed from those who responded, and thus responses may have been biased.

It should also be noted that, although our sample is representative of adults in California with elevated psychological distress, findings may have limited external validity in other states. Likewise, although the state of California is economically, racially, and ethnically diverse, sample size limited the statistical power for subgroup analyses in which one might explore differences in outcomes according to these or other population characteristics. This would be a fruitful avenue for future research.