Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by impairment in multiple cognitive domains, including memory, language, visuospatial skills, and executive functions. Executive functions are those cognitive processes that orchestrate the performance of complex, goal-oriented tasks and behaviors.

1 These abilities include motivation, strategy development and adjustment, response control, and abstraction, and they are mediated primarily by prefrontal brain regions.

2,3 Impairment of executive functions occurs in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders, including dementias, schizophrenia, and major depression.

4–6 The effect of AD on executive functions is poorly understood. Limited data suggest that executive dysfunction is common in AD

2 and is associated with delusions,

7 rapid progression of dementia,

8 and a need for a high level of care.

5Agitation, psychosis, depression, and apathy are common neuropsychiatric disturbances in patients with AD. Such neuropsychiatric symptoms may result in increased caregiver distress,

9 a higher rate of nursing home placement,

10 and more rapid disease progression.

11,12 Neuroimaging and neuropathologic studies indicate that neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with dysfunction in specific brain regions and that dysfunction of the frontal cortex may be particularly relevant to noncognitive expressions of the illness.

13–16There is little consensus on the relationship between cognitive deficits and the neuropsychiatric symptoms that occur in patients with AD; different studies have found no association,

17 a positive correlation,

18 weak positive associations,

19,20 a negative association,

21 and mixed relationships.

22 Studies of cognitive deficits and mood symptoms have also revealed mixed results.

23–27 The relationship between cognitive impairment and functional disability is better supported.

28,29 Most of these studies used measures of global cognition such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),

30 which contains memory, language, and visuospatial items, but not tests of executive function. The relationship between executive dysfunction and neuropsychiatric or functional status remains unclear.

We evaluated the presence and the extent of executive dysfunction in patients with AD. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and overall functional ability were also measured. The goals of this study were to 1) test the hypothesis that executive dysfunction is associated with greater neuropsychiatric symptomatology and functional impairment, and 2) explore relationships between executive dysfunction and specific types of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

DISCUSSION

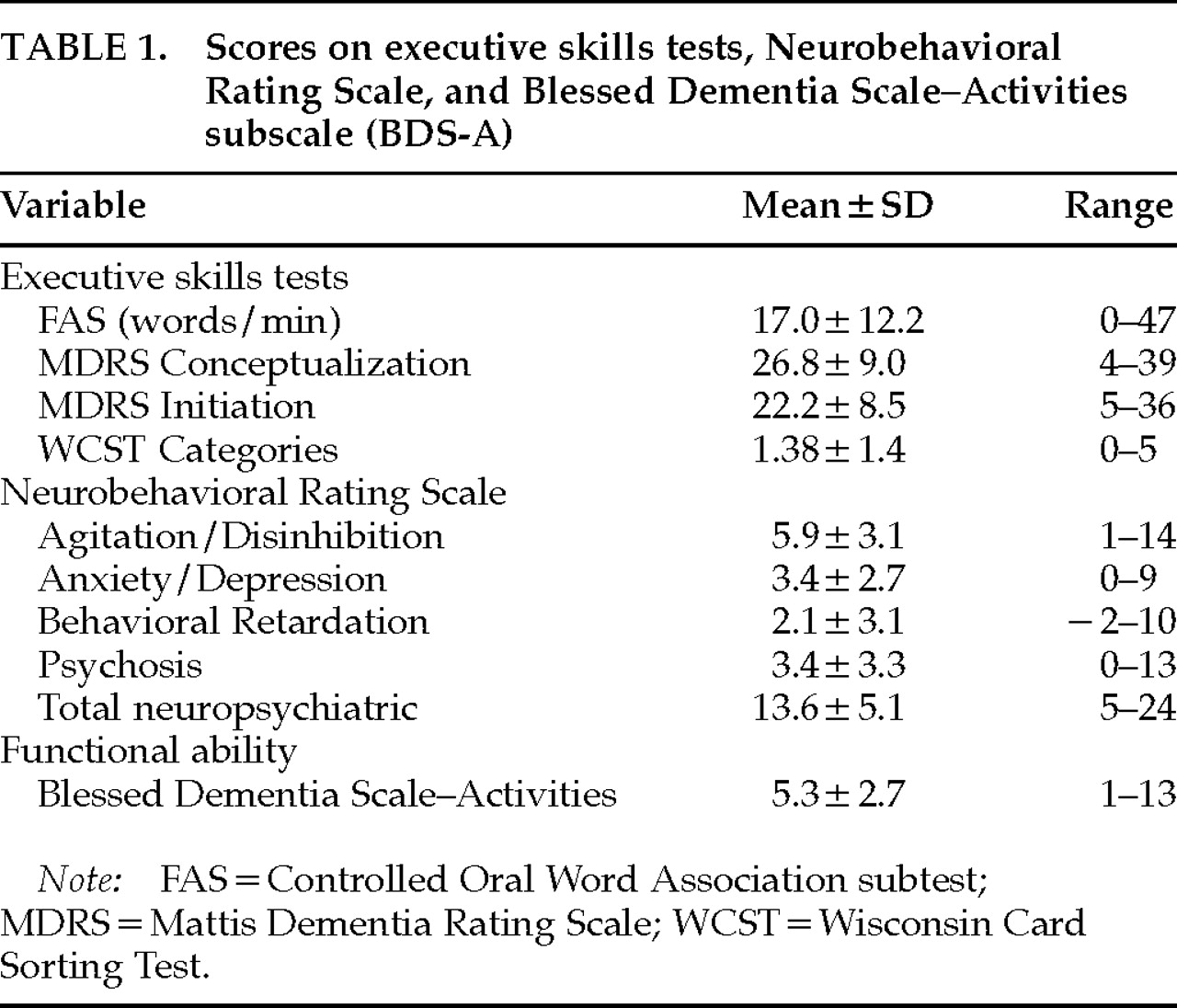

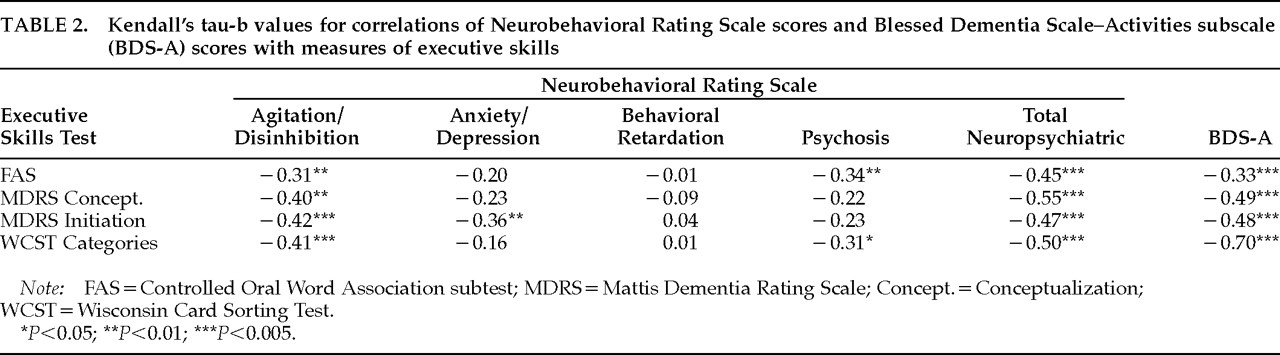

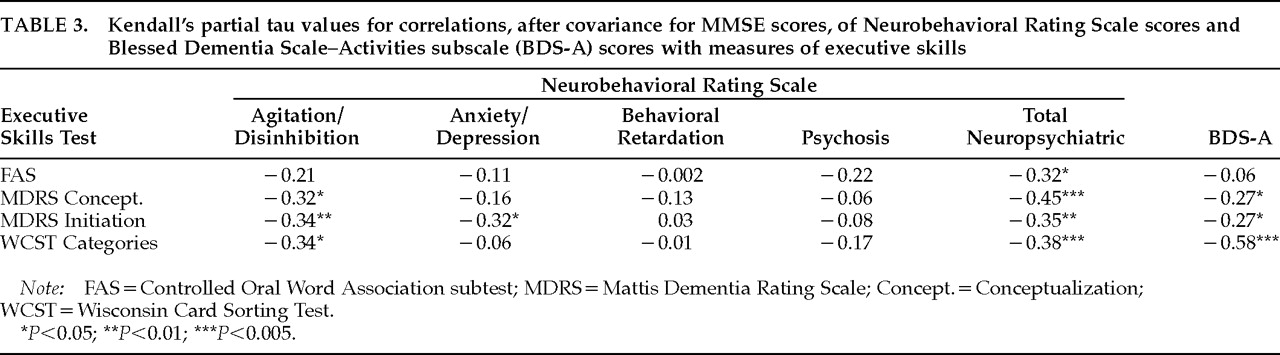

In this study of patients with AD we found significant relationships between executive dysfunction and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Poor performance on four tests of executive functioning was significantly associated with greater degrees of agitated and disinhibited behaviors, as well as overall neuropsychiatric disturbance. Spearman correlation coefficients for these relationships ranged from –0.58 to –0.68, indicating that scores on executive skills tests accounted for 34% to 46% of the variance of the NRS Total Neuropsychiatric scores. Low scores on tests of executive function were also associated with psychosis and with anxiety and depression, although not for all tests and not as strongly. There was no association between executive dysfunction and scores reflecting apathy, blunted affect, and psychomotor retardation.

The majority of these relationships between executive dysfunction and neuropsychiatric symptoms were independent of MMSE scores, suggesting that there is greater specificity for executive deficits that extends beyond global cognitive abilities. Previous studies that examined the relationships between cognition and behavior in patients with AD did not focus on specific areas of cognition.

17–19,21–26 Two studies compared the neuropsychological profiles of dementia patients with and without delusions. Jeste et al.

7 reported that AD patients with delusions performed more poorly on tests of memory, conceptualization, and verbal fluency than those without delusions. Flynn et al.

20 found that the delusional group had more difficulty with abstraction. Neither study controlled for degree of dementia or examined other types of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Our study demonstrates that a focused area of cognitive impairment, loss of executive skills, is accompanied by, and is a possible marker for, neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD, beyond the effects of global cognitive impairment.

Executive dysfunction was also significantly associated with inability to perform daily activities in this group of patients with AD. The relationship between WCST Categories scores and functional ability was particularly strong, and remained statistically significant after covariance with MMSE. The Spearman correlation and Spearman partial correlation coefficients for this relationship were –0.82 (

P<0.005) and –0.58 (

P<0.005), respectively, indicating that scores on this test accounted for more than 67% of the variance in scores of functional ability without controlling for MMSE, and 34% of the variance after controlling for MMSE. The ability to perform daily living activities to care for oneself may thus require a cognitive flexibility and a resistance to interference or distraction that are independent of overall level of cognition. The presence of executive skills deficits in a patient with AD therefore has important clinical implications for the level of care that the patient requires. Previous studies on AD, using other measures, have found relationships between cognition and functional impairment,

28,29 although none, to our knowledge, has investigated specific areas of cognition in this regard. In a study of young, chronically ill schizophrenic inpatients and elderly residents in a retirement community, Royall et al.

5 found that a measure of executive function was better correlated than MMSE scores with functional status in each group, suggesting that executive dysfunction has a substantial role in determining patients' level of functioning that is perhaps more important than global cognitive impairment, age, or disease.

Low executive skills scores were not associated with severity of all neuropsychiatric symptoms. Significant independent relationships were observed with agitated and disinhibited behaviors but did not appear with symptoms such as blunted affect and emotional withdrawal. These contrasting results suggest that executive deficits are not a proxy for generalized, overall morbidity, but that there is a specific connection between difficulty organizing and planning and the active, agitated, and disinhibited behaviors of AD. Such executive difficulties may have particular relevance to the ability to conform behaviors to socially appropriate norms. It is noteworthy that scores on the MDRS Conceptualization subtest, which measures the ability to recognize group similarities and differences and to appreciate metaphoric meaning, were associated with agitated behaviors and functional deficits. This finding suggests that difficulty with such “higher order” skills of abstract, inductive reasoning, which extend beyond the “organizational” executive skills such as fluency, planning, and strategy formation, is relevant to behavioral symptoms in patients with AD.

Underlying neurobiologic correlates may provide the basis for the relationships between executive dysfunction and specific neuropsychiatric symptoms. Both executive functioning and many neuropsychiatric disturbances are mediated through frontal-subcortical circuits.

40 The dorsolateral prefrontal circuit facilitates executive functioning, and neuroimaging and neuropathologic studies implicate frontal cortical involvement in psychosis associated with AD.

14–16 Our previous results demonstrated a relationship between global frontal cortical hypometabolism and NRS total score, NRS Agitation/Disinhibition factor score, and Psychosis factor score in patients with AD, and a lack of association between frontal metabolic rate and the NRS Anxiety/Depression or Behavioral Retardation factor scores.

16 Thus, deficits in executive skills, agitated behaviors, and functional disability in AD may share pathophysiologic processes in the frontal cortex, whereas apathy and blunted affect may not be associated with executive skills deficits and may be due to dysfunction outside the frontal lobe or to dysfunction in discrete subregions of the frontal cortex.

Other factors may be involved in the observed relationships between executive dysfunction and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Executive dysfunction may therefore be a marker of frontal lobe dysfunction but not etiologically related to neuropsychiatric phenomenology. The presence of neuropsychiatric disturbances could interfere with performance on executive skills tests. However, one would then expect behavioral retardation to be associated with initiation and cognitive flexibility. No such association was found. Nor was speed of performance relevant; the FAS test, which is timed, was the least associated of the tests with agitation, total neuropsychiatric symptomatology, and functional disability.

Other methodologic issues should be considered in interpreting the results of the study. The presence of small periventricular hyperintensities on MRI, which was not an exclusion criterion, may affect executive function.

41 The neuropsychological tests selected depend on cognitive domains other than executive functioning, and therefore may not be “clean” measures of executive skills. (The WCST requires motor and visuospatial abilities; the FAS and MDRS tests call on language skills.) Conversely, the MMSE has been associated with executive functioning in AD

42 and therefore may not be an ideal covariate to account for the effects of global cognitive impairment.

The results of this study suggest that agitated, disinhibited behaviors and deficits in self-care activities are associated with executive dysfunction in AD. In relation to noncognitive disturbances in AD, measurement of executive skills may be at least as important as measurement of global cognitive status. These findings have important clinical implications. Executive skills are not routinely assessed in patients with AD, although such assessment may assist the clinician in determining the patient's need for assisted living or psychiatric intervention. That three of the seven proposed executive skills tests could not be performed by 32% to 55% of a moderately impaired AD group suggests a need for better measures of executive skills in this population, as well as the possible utility of such measures in earlier detection of AD. Known neuroanatomic circuits and pathophysiologic observations support the relationships among frontal lobe dysfunction, deficits in executive skills, and certain neuropsychiatric symptoms. These data support the further study of executive dysfunction in AD, including the longitudinal course of deficits, associated neuropsychiatric disturbances, efficacy of treatment, and more precise elucidation of neurobiologic mechanisms.