Two studies of delirium subtypes based on psychomotor activity levels

9,10 have found that patients with hyperactive phenomenology had shorter hospital stays and better outcomes than either mixed or hypoactive subtypes. In a similar study, Meagher et al.

11 found a number of associations between phenomenologic subtypes and ward management practices, including more frequent use of psychotropic medications and environmental manipulations in hyperactive cases. Hyperactive presentations of traumatic brain injury delirium have a better physical and cognitive prognosis than hypoactive presentation.

12 Hyperactive delirious medical patients (alcoholics excluded) had a high rate of full recovery, whereas mortality was highest in the mixed subtype.

13 If such motoric subtypes have distinctive symptom patterns, these may reflect separate pathophysiological processes and may have differing responsivities to the range of somatic interventions that are becoming increasingly available for the management of this complex condition. Thus far, only alcohol withdrawal delirium is associated with a different EEG and SPECT scan presentation than other forms of delirium.

14In this study, we investigated the relationship between motoric subtypes and delirium symptoms in order to better understand delirium phenomenology. We used standardized delirium symptom ratings in conjunction with a previously published definition of three motoric subtypes to describe a general hospital consecutive sample of consultation-liaison referral patients.

DISCUSSION

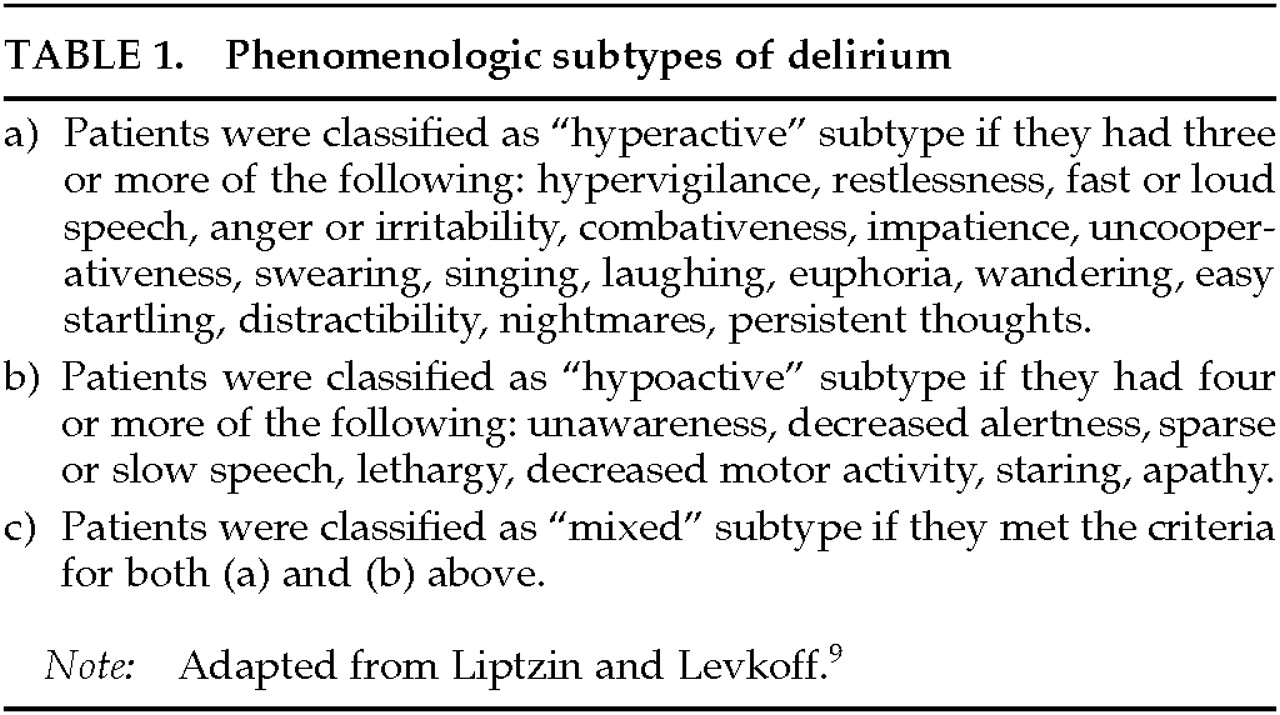

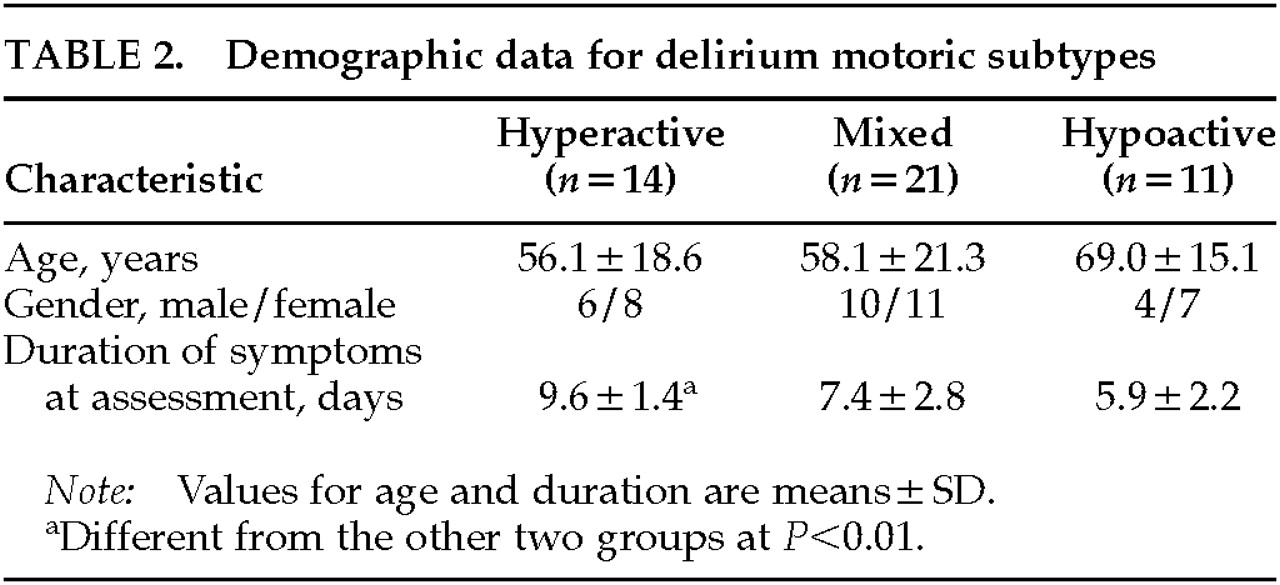

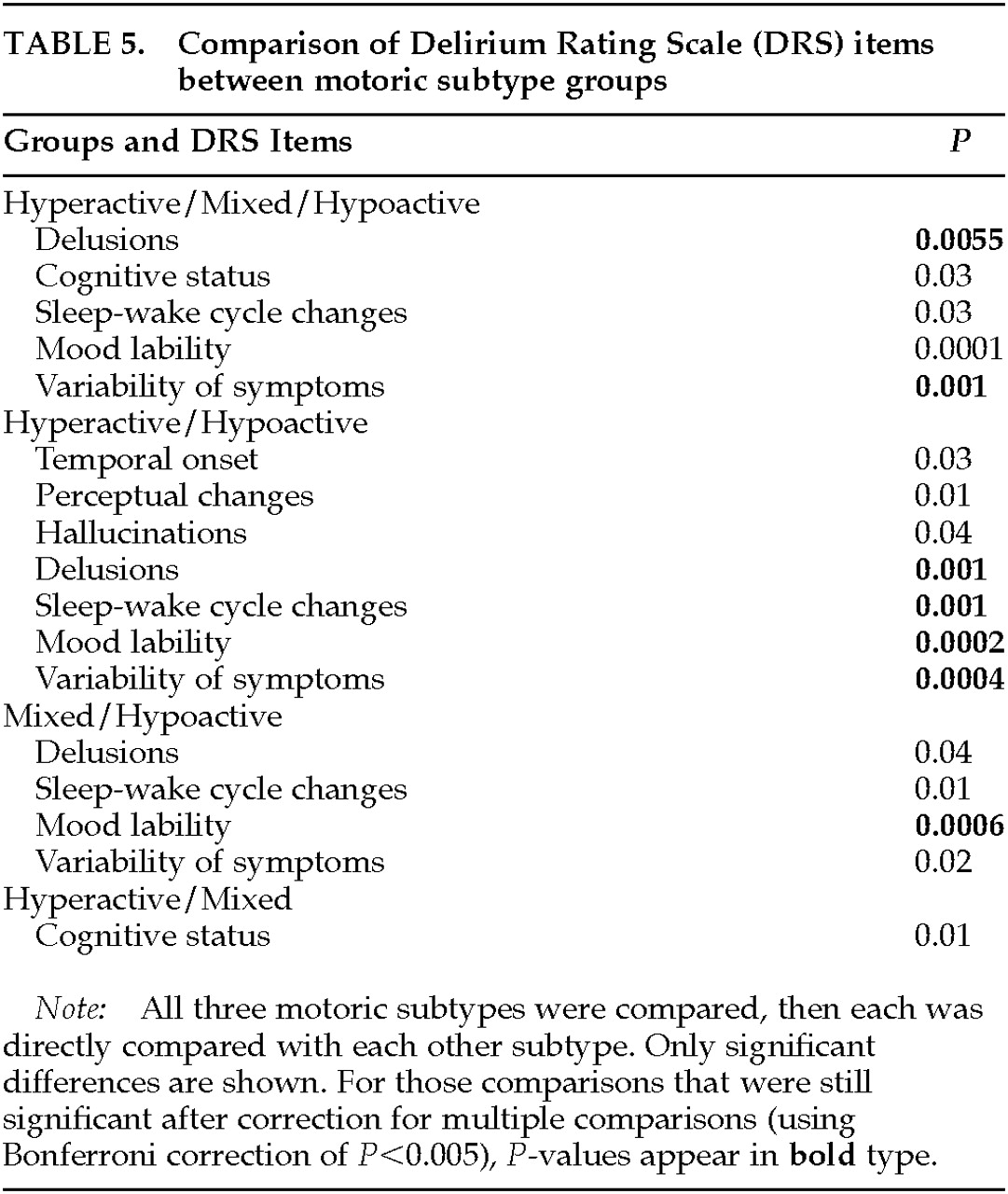

We have described 46 consecutively referred delirium patients who met ICD-10 criteria, with the aim of studying the relationship between specific delirium symptoms and motoric subtypes that were independently assessed. We used the DRS to rate severity of individual symptoms and compared these among three groups (hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed) distinguished by their psychomotor presentations according to criteria first delineated by Liptzin and Levkoff.

9 The DRS, unlike the subtype criteria, does not make

a priori assumptions about which behavior or motoric symptoms might differentiate hyper- from hypoactive presentations of delirium. Furthermore, the Liptzin and Levkoff subtype classification includes many symptoms that are not rated in the DRS, although two DRS items (psychomotor behavior and mood lability) would be likely to overlap. In addition, the DRS psychomotor item does not distinguish hypo- from hyperactive cases, instead rating only the severity of either presentation. Using these assessment tools, we found that several delirium symptoms significantly distinguished the motoric subtypes. Our findings are consistent with a previous study of phenomenologic subtypes of delirium

17 that used different measurement tools. Our findings provide support for the suggestion that the syndrome of delirium is composed of a collection of separate components or symptoms, the expression of which might vary according to different etiologies.

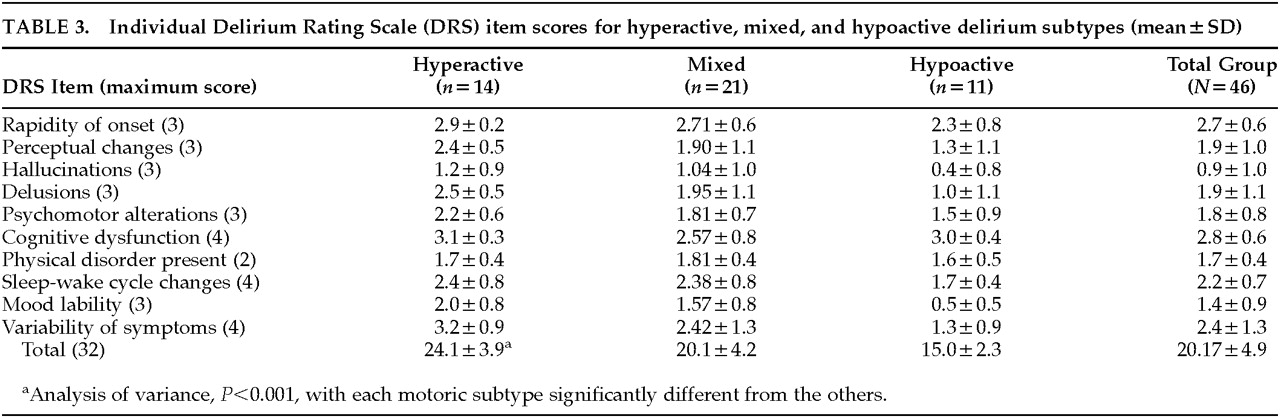

Overall DRS scores significantly distinguished the motoric subtypes, with mean scores for the hyperactive subtype more than 9 points greater than for the hypoactive subtype. The mixed subtype was intermediate between these extremes, and, surprisingly, no item score distinguished this group from hyperactive cases, even though the mixed group's total DRS score was significantly lower. The symptoms that contributed to the differences among the three groups were delusions, mood lability, and variability of symptoms. Hypoactive and hyperactive groups also differed on sleep-wake cycle disturbances. Interestingly, items with similar scores among the three groups included temporal onset, cognitive impairment, physical disorder, and sleep-wake cycle disturbance. Although also not significantly different, scores for psychomotor behavior, hallucinations, and perceptual disturbances were highest for the hyperactive group and lowest for the hypoactive group.

In findings similar to ours, Ross et al.

17 found no difference in cognitive functioning, using the Mini-Mental State Examination, between hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes. However, they did find that agitated behavior, psychosis, mood lability, rapid speech, and incoherence were more common in hyperactives. Similarly, Koponen et al.

18 found no differences in EEG spectral analysis or cognitive function between hyper- and hypoactive patients.

Lipowski,

19 however, described a third, “mixed,” group that Ross et al.

17 did not report. Subsequent studies suggest it may in fact be the most common form of the syndrome.

9,11,18 It has been suggested that this mixed category is simply a reflection of the inherent variability of delirium and the tendency of many patients to fluctuate in their symptom severity—although any symptom (mood lability, psychosis, cognition) can fluctuate, not just psychomotor behavior. It is possible that those patients who fall into this mixed group have endured a longer duration of delirium at the time of assessment, with more opportunity for multiple causes to contribute to symptom profile. However, Rudberg et al.

20 assessed the pattern of delirium symptoms occurring in hospitalized elderly patients, using daily DRS ratings, and found that there were no patterns of change over time in specific DRS items. When Liptzin and Levkoff

9 studied these subtypes in relation to delirium course and outcome, they found that patients of the mixed subtype had longer hospital stays and higher 6-month mortality rates than the other groups.

Our hyperactive group had a longer duration of recognized delirium at the point of referral than the other motoric subtypes. However, previous work has suggested that hyperactive patients are recognized and referred earlier because of the management problems that their behaviors present and that less active patients are more likely to go unnoticed or be misdiagnosed as depressed.

21 This discrepancy may be related to the higher rate of intervention with psychotropic medications that is associated with hyperactive presentation of delirium.

11,22 The relative delay in consultation in hyperactive cases may be due to an initial misdiagnosis of psychosis, or it may reflect an observation period after the commencement of pharmacologic intervention by the primary team. It may also be a reflection of the broad range of symptoms used in addition to motor activity to define the motoric subtypes in our study—which in hyperactive patients would include behavioral symptoms that get the attention of caregivers. A study of consecutively admitted patients who are at risk of delirium, and not a referral sample, could address this methodological problem. In view of evidence indicating differing management practices between motoric subtypes of delirium,

11 further work is needed to investigate to what extent the superior outcome noted in patients of hyperactive motoric profile is related to earlier recognition, more active management, or underlying pathophysiology.

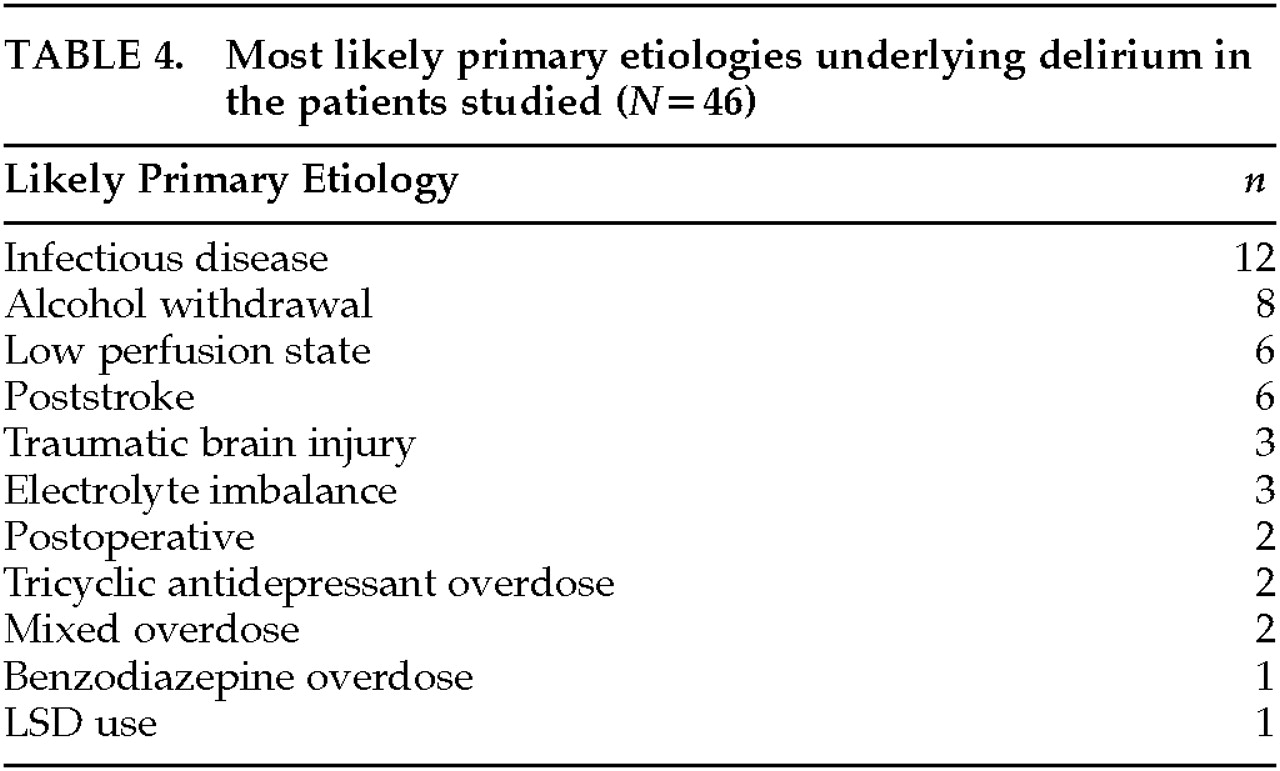

The relationship between symptoms or subtypes of delirium and underlying etiology is an uninvestigated area, except for substance-related deliria. Recent work suggests that, for example, delirium due to drug withdrawal is more likely to be of the hyperalert-hyperactive type and metabolic encephalopathy is more likely to be of the hypoactive-hypoalert type.

17 In addition, other work has suggested that different delirium subtypes may be associated with particular disruption of the activity of specific neurotransmitter systems.

23 For example, anticholinergic intoxication states and delirium from traumatic brain injury may be more often hyperactive. Delirium from traumatic brain injury, stroke, hypoxia, thiamin deficiency, and hypoglycemia may be due to reduced CNS cholinergic activity,

14 but motoric subtype has not been systematically studied in these etiologic groups. Other evidence suggests that sedative-hypnotic and alcohol-related causes of delirium are associated with disturbances of GABAergic activity, at least in part.

14If different etiologies for delirium have distinctive symptom profiles, these may reflect differing pathophysiological patterns. The relationship between etiology and motoric subtype warrants a well-designed prospective study. Such study may provide important insights into crucial aspects of delirium management, including differing responsiveness to the increasing range of therapeutic modalities available for the treatment of delirium.

Although these data provide support for a number of important relationships between phenomenology and motoric subtype of delirium, the study has a number of limitations. The findings relate to referrals to a general hospital consultation-liaison service and thus may not be generalizable to other populations. The sampling methods may have led to an overrepresentation of certain delirium subtypes or particular problems encountered in delirious patients. Referral samples also make the assessment of symptom duration more difficult. Our group included 6 cases with a suspected underlying dementia that may have altered the presentation of delirium.

14 However, in a recent factor-analysis comparison of delirious and delirious-demented elderly patients, it appeared that delirium phenomenology largely overshadowed dementia symptoms, although the groups were not completely alike.

24 The DRS has many advantages for application in studies of this type, but it does not specifically include an item related to attention levels, which are considered by some researchers to be a fundamental feature of delirium, nor does it separate motoric subtypes into separately rated items. The use of standardized cognitive tests in addition to the DRS might have elucidated more subtle differences in severity or type of cognitive impairments among motoric subtypes. Future studies of motoric subtypes should include 24-hour objective motor activity monitoring in addition to clinical ratings.