The term “postconcussional syndrome” refers to a group of symptoms, including headache, dizziness, fatigue, and affective and cognitive changes, that may be reported by patients after traumatic brain injury (TBI).

1 Criterion-based diagnoses for postconcussional syndrome were proposed during the 1990s as part of the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)

2 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).

3 Most research on postconcussional syndrome has been confined to studying individual symptoms, resulting in a gap in understanding the formal properties of the syndrome as a categorical diagnosis.

4 In this article, the initial study of agreement between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses of postconcussional syndrome is reported.

The DSM-IV proposed the diagnosis of postconcussional disorder using six diagnostic criteria: (A) history of TBI causing “significant cerebral concussion;” (B) cognitive deficit in attention and/or memory on formal testing; (C) occurrence of three or more postconcussional symptoms (fatigue, sleep disturbance, headache, dizziness, irritability, affective disturbance, personality change, or apathy) soon after injury and persisting ≥3 months; (D) symptoms are of new onset or worsening of preexisting symptoms; (E) symptoms interfere with social role functioning; and (F) exclusion of dementia due to head trauma (294.1) or other disorders that better account for the symptoms. Criteria C and D set a symptom threshold requiring a latency of onset, minimum symptom duration, and discriminability from preexisting symptoms. The criteria were published in the appendix of “Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study,” which did not have sufficient information to be included as official categories in DSM-IV.

Diagnostic criteria for the ICD-10 clinical diagnosis of postconcussional syndrome (code F07.2) are limited to a history of TBI and three or more of the following symptoms: headache, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, insomnia, difficulty with concentration or memory, and intolerance of stress, emotion, or alcohol.

2 In contrast to DSM-IV, the ICD-10 criteria do not require objective cognitive deficit, clinical significance, or exclusion of other disorders and do not provide a symptom threshold.

The purpose of this study was to investigate agreement between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses of postconcussional syndrome in adults with mild to moderate TBI who were studied prospectively during the first few months postinjury. Because of differences between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria, it was hypothesized that agreement between the DSM-IV diagnosis of postconcussional disorder and the ICD-10 diagnosis of postconcussional syndrome would be limited.

METHODS

Patient Sample

Study subjects were unselected, prospectively enrolled patients diagnosed with TBI at Ben Taub General Hospital, a Level I trauma center in Houston, Tex., during a 2-year period (January 1999 to February 2001). Selection criteria were 1) nonpenetrating TBI with lowest postresuscitation Glasgow Coma Scale

5 score >8; 2) arrival to the trauma center within 24 hours of injury; 3) blood alcohol level <200 mg/dl; 4) computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain performed within 24 hours of injury; 5) age 16 years or older; 6) fluent English or Spanish speaker; 7) residence in Harris County, Tex., the hospital catchment area; 8) not an undocumented alien, not incarcerated, not homeless, or not on military service; 9) no spinal cord injury; 10) no prior hospitalization for TBI; 11) no history of substance dependence, mental retardation, psychosis, or central nervous system disturbance; and 12) no other condition preventing standard administration and interpretation of the outcome measures. The hospital emergency center protocol for management of TBI provided for CT scan of the head for patients with a history of impaired consciousness. Mild TBI was defined as a closed head injury producing a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13–15 upon arrival, with no later deterioration of Glasgow Coma Scale <13 and no surgery under general anesthesia. Moderate TBI was defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 9–12 upon arrival, with no later deterioration of Glasgow Coma Scale <9.

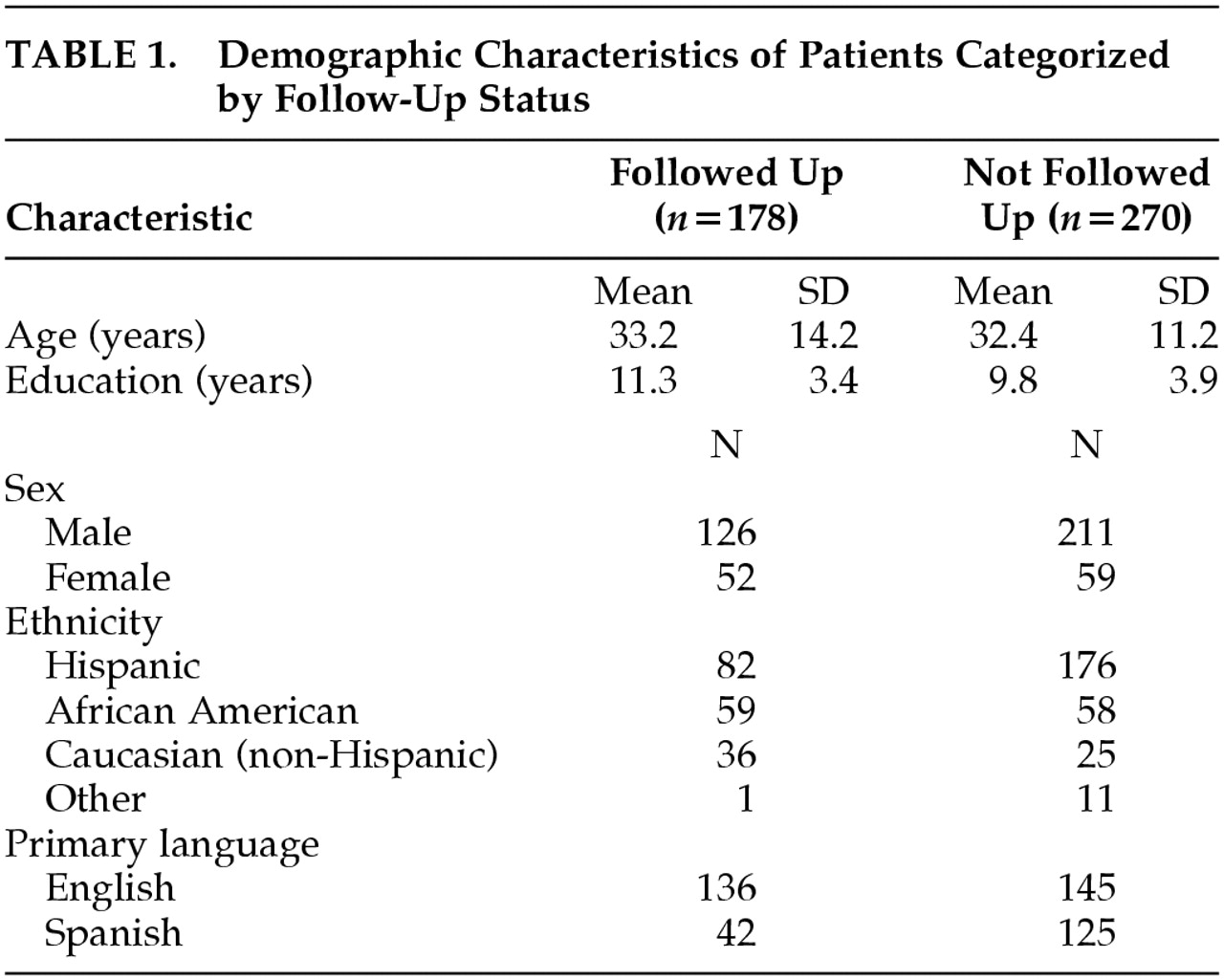

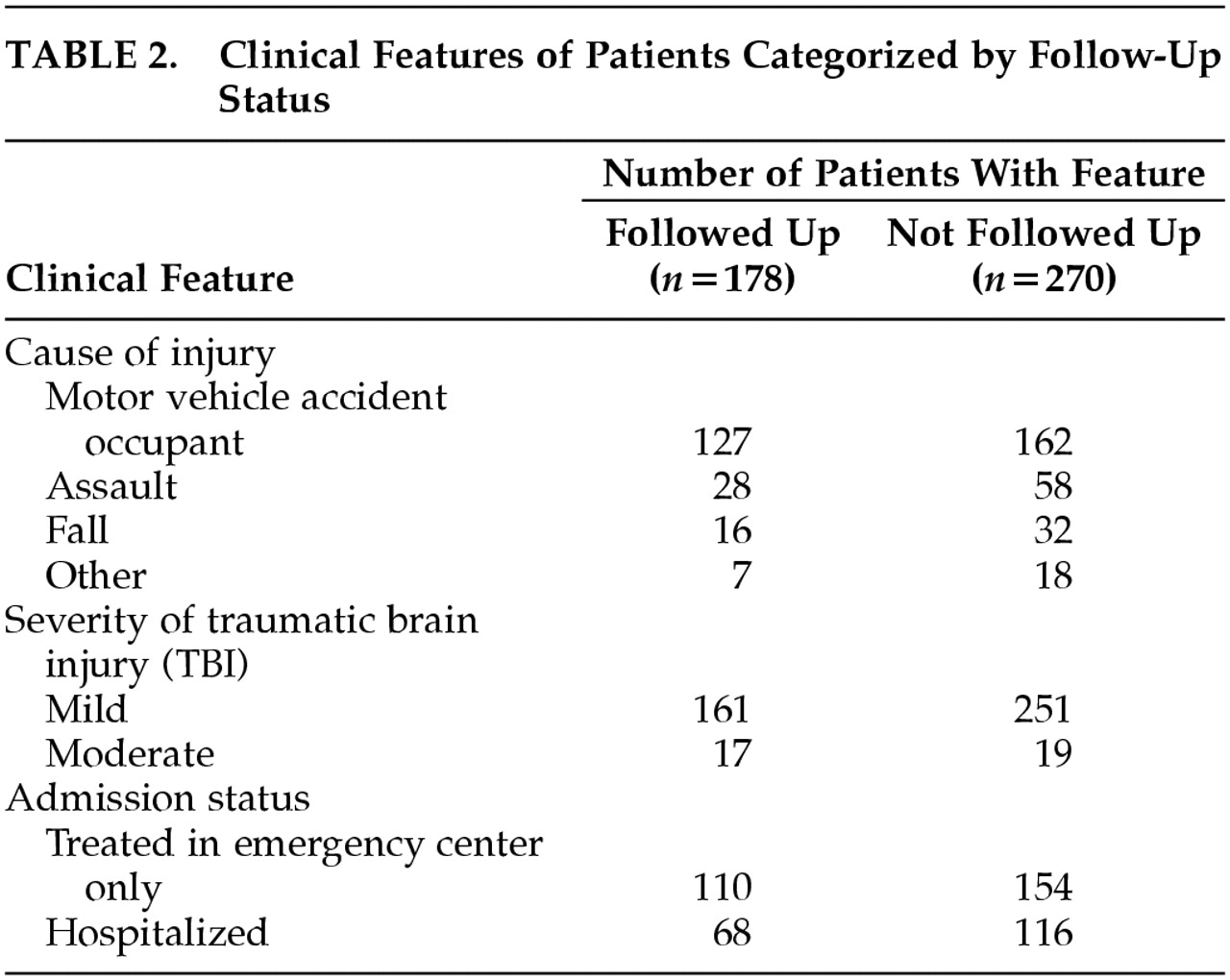

Of 448 patients who met the above criteria and were enrolled in the study, 178 (40%) were followed up 3 months after injury.

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the demographic and injury features of the sample. The modal patient was a young adult male injured in a motor vehicle accident, which is consistent with epidemiological studies of TBI in the U.S. adult population.

6 Representation of Hispanic and African American ethnicities is consistent with the hospital catchment area.

Comparison between patients who were and were not followed up (using t tests or chi-square tests at a 95% confidence level) found that follow-up was unrelated to age, sex, occupation, cause of injury, and Glasgow Coma Scale score. The 270 patients lost to follow-up were more likely to be Spanish speakers, of Hispanic ethnicity and to have less formal education.

Outcome Measures

Structured interview for postconcussional syndrome.

A structured interview was developed to evaluate the DSM-IV and ICD-10 postconcussional syndrome criteria, consisting of questions directed to the patient in order to determine whether the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria were met. Some questions were adapted from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders

7 and the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale—Revised,

8 which evaluate many of the same symptoms included in the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. When a symptom was present, the interview branched to address additional questions that determined whether the symptom met the thresholds of DSM-IV and/or ICD-10. For study purposes, the ICD-10 symptom threshold was arbitrarily set to 1-week duration.

Neuropsychological testing.

Three neuropsychological tests were administered following standard procedures. In the Rey Complex Figure,

9 which is a measure of visual declarative memory, the patient copied a geometric design and drew the design from memory immediately afterward and again after 30 minutes. In the Selective Reminding Test,

9 a measure of verbal declarative memory, the patient recalled words from a list read aloud for six trials, without being reminded of words recalled on the preceding trial. Delayed recall was tested after 30 minutes. In the Symbol Digit Modalities Test,

10 which is a measure of working memory and visual-motor performance speed, the patient, using either spoken or written responses, converted a list of printed symbols to digits according to a digit-symbol correspondence key. These tests were selected because of their sensitivity to attention and memory deficits following TBI.

11–14 Six test scores were obtained: 1) correct reproductions of Complex Figure elements (0–36) at 30 minutes; 2) Selective Reminding Test (SRT) long-term storage sum (0–72), 3) consistent long-term retrieval sum (0–72), 4) and words recalled at 30 minutes (0–12); 5) correct Symbol Digit Modalities Test oral and 6) written responses (0–110). A test score was classified as abnormal if the score was at least one standard deviation (SD) away from the normal average in the direction of impairment. Normal averages and SDs were taken from a sample of 104 adults who had suffered trauma not involving the brain, were demographically similar to the TBI sample, and were recruited and tested following the same procedures used with the TBI patients.

15,16 Test scores were statistically adjusted for age, education, racial/ethnic group, and primary language in order to remove the influence of demographic background on the cognitive impairment criterion.

DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses.

DSM-IV postconcussional disorder was diagnosed if interview responses satisfied criteria C (symptoms), D (symptom threshold), and E (clinical significance) and if at least one neuropsychological test score was statistically abnormal as defined above. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criterion A (history of TBI) was presumed to be fulfilled because the selection criteria required a diagnosis of TBI. Criterion F (exclusion) was presumed fulfilled since the selection criteria should have excluded preexisting disorders with similar symptoms. Overlap with Dementia Due to Head Trauma and other DSM-IV cognitive disorders were not evaluated. International Classification of Diseases-10 postconcussional syndrome was diagnosed if the patient indicated that at least three of the ICD-10 symptoms had been present 1 week preceding the follow-up evaluation. The ICD-10 history of TBI criterion was presumed fulfilled because of the selection criteria, but loss of consciousness was not required.

Procedure

Patients were prospectively enrolled at the trauma hospital in the emergency center or during hospitalization. Diagnoses of TBI and Glasgow Coma Scale ratings were made by hospital staff. The follow-up evaluation was a face-to-face interview at 3 months (±1 month) conducted in the patients' primary language by a research assistant. During the follow-up evaluation, which took place on average at 85.8 days (SD=20.3) after injury, the structured interview and neuropsychological tests were administered. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of participating institutions, and patients gave informed consent after study requirements were explained.

Statistical Analysis

The kappa statistic and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to quantify agreement between the ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria and between the five postconcussional symptoms that appear in both criteria sets. Kappa is the ratio of the proportion of cases in which these two diagnoses agree to the maximum proportion of cases in which the diagnoses could agree.

17 Higher kappa values indicate better agreement; for example, kappa=0.2 indicates slight agreement and kappa=0.8 indicates substantial agreement. Analyses were performed with Statistical Analysis System for Windows, version 8.2.

18RESULTS

Concordance Between Diagnoses of Postconcussional Syndrome

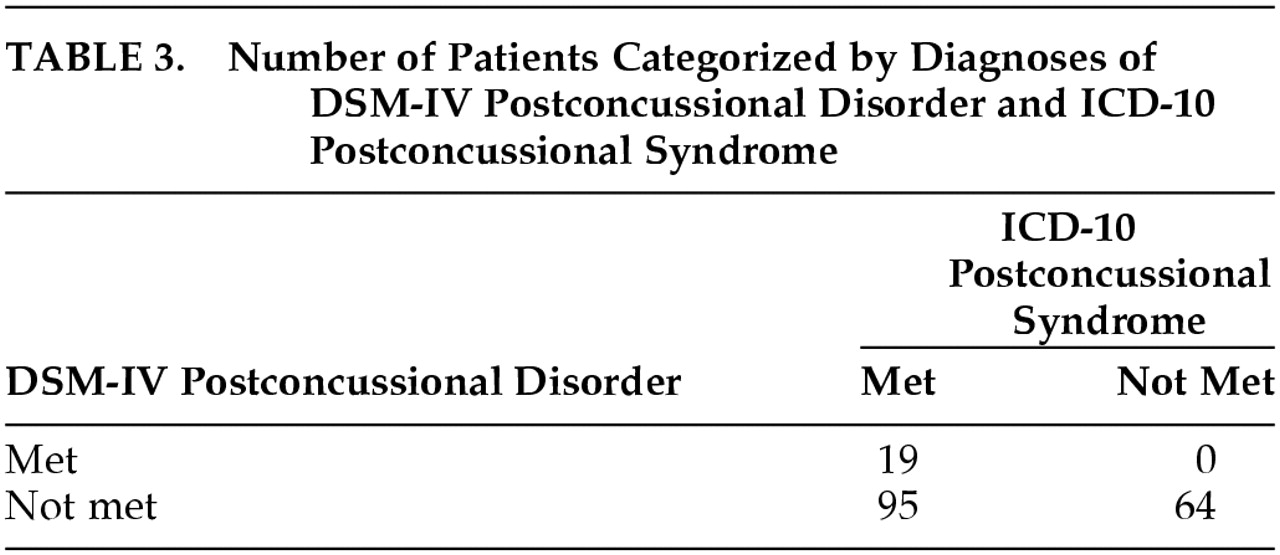

Table 3 presents the cross-classification of patients by the full DSM-IV postconcussional disorder and ICD-10 postconcussional syndrome criteria. Agreement between the two criteria-based diagnoses occurred in 46% of patients. The kappa statistic indicated slight agreement between these two diagnoses (kappa=0.13, 95% CI=0.01–0.25). However, some concordance is shown by the fact that all patients who met the DSM-IV criteria also met the ICD-10 criteria. In addition, no patient who failed to meet the ICD-10 criteria met the DSM-IV criteria. Of patients who met the ICD-10 criteria, only 17% also met the DSM-IV criteria, suggesting that DSM-IV postconcussional disorder has a higher threshold or greater specificity than ICD-10 postconcussional syndrome. The paradoxically low kappa value may reflect differences between the prevalences and thresholds of the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses.

19 DSM-IV Cognitive Deficit Criterion

Fifty-six of 178 TBI patients (31.5%) met the DSM-IV cognitive deficit criterion, which is defined as having at least one statistically abnormal test score. The percentages of patients with abnormal scores were 6.3% on the oral Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), 14.6% on the written Symbol Digit Modalities Test, 13.6% on the Selective Reminding Test long-term storage, 17.6% on the Selective Reminding Test consistent long-term retrieval, 28.2% on the Selective Reminding Test 30-minute delayed recall, and 12.8% on the Complex Figure 30-minute delayed recall.

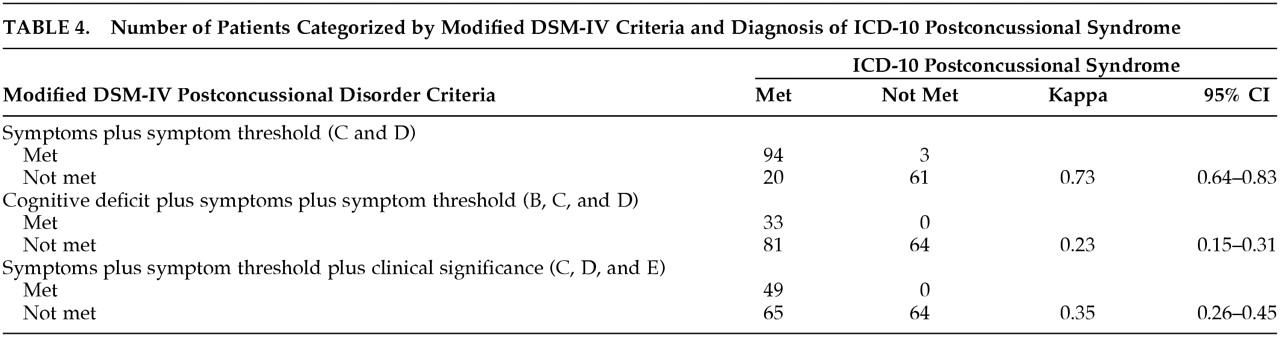

Effect of Selected DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria

Table 4 presents the cross-classification of patients by the full ICD-10 criteria and three modified DSM-IV criteria sets, created by removing the DSM-IV cognitive deficit criterion and/or clinical significance criterion. Removing both of these criteria reduces DSM-IV postconcussional disorder to the two symptom criteria (C and D), resulting in a criteria set similar to that of ICD-10 postconcussional syndrome. As shown in the upper panel of

Table 4, the ICD-10 diagnosis was in substantial agreement with the modified DSM-IV symptom criteria. Of patients who met the ICD-10 criteria, 82% also met the modified DSM-IV symptom criteria.

As shown in the middle and lower panels of

Table 4, when the DSM-IV cognitive deficit or clinical significance criteria are required, the number of patients meeting the DSM-IV criteria dramatically decreases. Of patients meeting both the DSM-IV and ICD-10 symptom criteria, approximately one-third also met the DSM-IV cognitive deficit criterion and about one-half met the clinical significance criterion. Therefore, DSM-IV cognitive deficit and clinical significance criteria appear to be major causes of the limited agreement between DSM-IV postconcussional disorder and ICD-10 postconcussional syndrome.

Agreement Between DSM-IV and ICD-10 Symptoms

Table 5 presents the agreement between the five symptoms (headache, fatigue, sleep disturbance, irritability, and dizziness) that overlap between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. Agreement could not be determined for the remaining three DSM-IV and ICD-10 symptoms that do not overlap between the criteria sets. Frequency of endorsement was about equal for the symptoms of headache, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and irritability, which have traditionally been included in descriptions of postconcussional syndrome.

1 All five symptoms overlapping the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria agreed very closely. Each ICD-10 symptom, except for sleep disturbance, was slightly more prevalent than the same symptom in DSM-IV. This discrepancy is expected due to the higher symptom threshold set by DSM-IV criteria C and D. Sleep disturbance is exceptional because this symptom is limited to insomnia in ICD-10, while it also includes excessive sleep in DSM-IV. Therefore, these results show that the concordance between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 symptom criteria is also found at the level of individual symptoms, despite differences in symptom thresholds.

DISCUSSION

The limited agreement between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses is surprising given that the postconcussional syndrome has been in medical terminology since the 1930s.

20,21 Early descriptions of the postconcussional syndrome (also termed “postcontusional syndrome” and “posttraumatic syndrome”) emphasized the co-occurrence of a group of symptoms dominated by headache. The postconcussional syndrome category, as introduced into ICD-9 during the 1970s,

22 was defined in terms of the traditional symptom picture. International Classification of Diseases-10 essentially translated the ICD-9 symptom picture into explicit diagnostic criteria. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV postconcussional disorder departed from the ICD approach by supplementing the traditional symptom picture with criteria that required cognitive impairment and clinical significance. The rationale for the DSM-IV clinical significance criterion seems to be clear since this is required in most Axis I disorders. The rationale for the DSM-IV cognitive deficit criterion has been criticized on the grounds that postconcussional symptoms occur frequently in the absence of detectable cognitive impairment.

4,23 The initial proposal for DSM-IV postconcussional disorder

24,25 does not discuss the ICD criteria.

This study found that the symptom features of DSM-IV postconcussional disorder, as represented in criteria C and D, are in substantial agreement with the ICD-10 diagnosis. If the DSM-IV postconcussional disorder were modified to include only criteria for history of TBI and postconcussional symptoms, the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses would agree closely. This level of agreement was unexpected because the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses use different symptom thresholds and only five of the eight postconcussional symptoms that are included in the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria are included in both criteria sets (

Table 5). For example, the ICD-10 criteria do not require the worsening of preexisting symptoms or that postconcussional symptoms be of new onset. The consistent but small differences in the frequency of DSM-IV and ICD-10 symptoms do not indicate that the stricter symptom threshold of DSM-IV had a large impact.

Agreement between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses was limited mostly by the cognitive deficit and clinical significance criteria of DSM-IV, which were satisfied at a much lower frequency than were the symptom criteria of either DSM-IV or ICD-10. Since patients meeting the DSM-IV criteria were a subgroup of those who met the ICD-10 criteria, the DSM-IV diagnosis may have a higher threshold or greater specificity. Given the criticisms of the DSM-IV cognitive deficit criterion for postconcussional disorder,

4,23 future studies could determine whether this criterion improves the utility of the diagnosis. It may also be helpful to investigate other procedures for implementing the cognitive deficit criterion. By defining cognitive deficit as having a single test score more than one standard deviation below the normal average, the present study set the cognitive deficit threshold in a way that maximized sensitivity while sacrificing specificity. Using a stricter threshold that required a greater deviation or a larger number of abnormal scores would have decreased sensitivity and therefore the prevalence of postconcussional disorder.

Certain methodological issues in this study need to be considered. First, the high attrition between enrollment and the 3-month evaluation may have introduced selection for certain demographic or clinical features. Greater proportions of Spanish speakers and Hispanic ethnicity among patients who were not followed up would seem to support this possibility. In preliminary analyses, Hispanic ethnicity was associated with decreased risk of DSM-IV postconcussional disorder.

15 Second, the structured interview format may have increased the frequency of symptom endorsement. In support of this possibility, Gerber and Schraa

26 found that mild TBI patients reported fewer symptoms in response to open-ended questions, as compared to questions that cued for each symptom. Third, other psychiatric or neurobehavioral disorders that were present in the study sample might have interfered with diagnosing the postconcussional syndrome. In preliminary analyses, more than 10% of TBI patients met criteria for major depressive disorder and this disorder often co-occurred with DSM-IV postconcussional disorder.

15,16 Therefore, some of the postconcussional symptoms (e.g., mood change) reported by the study patients may have been caused by anxiety or mood disorders. There is also a possibility that some of the patients who met DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria for postconcussional syndrome could have been classified under dementia due to head trauma. In DSM-IV, dementia criterion A requires memory impairment plus aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or executive dysfunction.

3 Attentional deficits are included in DSM-IV postconcussional disorder but do not appear in the DSM-IV dementia criteria. Although tests of aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia were not administered in this study, it is likely that few or no study patients would have met the DSM-IV dementia criteria because these impairments occur rarely in mild to moderate TBI.

Limited agreement between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses has important implications for clinical and research uses of the postconcussional syndrome diagnosis. Clinicians using this diagnosis must select from alternative criteria sets that may lead to diagnostic decisions that are inconsistent and even incompatible. In the absence of evidence about the relative advantages of the DSM-IV and the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for postconcussional syndrome, there is minimal justification for preferring either criteria set. Future studies could compare the available criteria sets in terms of interrater reliability, specificity, and prognostic value. It is even possible that a categorical diagnosis could turn out to be less appropriate than quantitative symptom scales, such as rating scales designed to measure the overall intensity of postconcussional symptoms.

27ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research for this study was supported by grants R49/CCR612707-01 (Depression after Mild to Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury) from the Centers for Disease Control and H133A70015 (Traumatic Brain Injury Model System of Institute for Rehabilitation and Research) from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. Presented in part at the meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, Chicago, February 14–17, 2001. We are grateful to Kim Chen, Edmund Dipasupil, Monica Freedman, Hector Garza, Maria Elena Gutierrez, Sean Little, Marianne MacLeod, Mary Nowak, Manuel Vasquez, and Christine Yeh for their assistance.