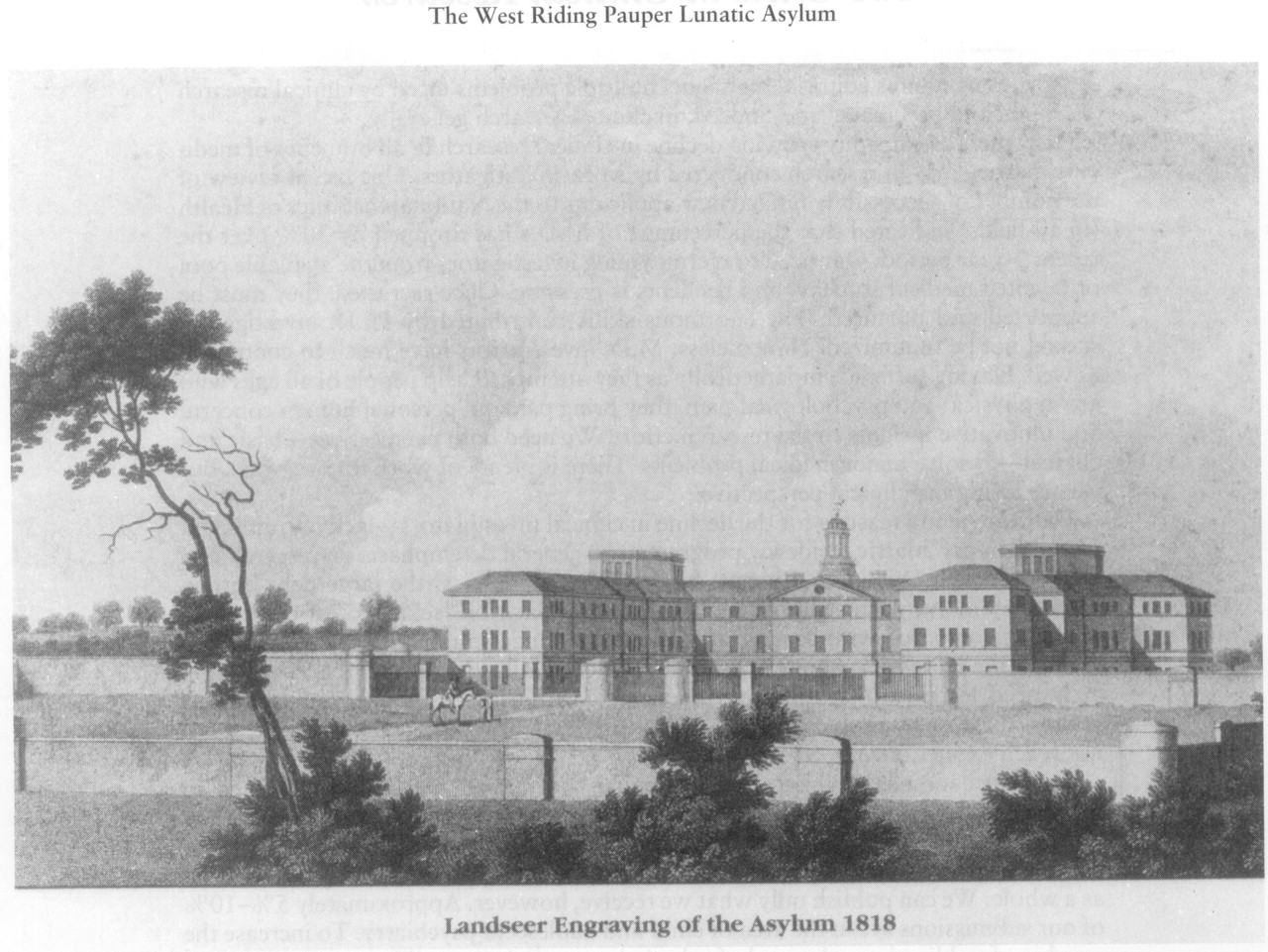

In the year 1808 the British Parliament passed an Act requiring all counties to establish an asylum for the care of the insane. The asylum in Yorkshire, the

West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum, was opened in 1818 at Stanley, near the city of Wakefield. In 1930, another Act discontinued the official use of the terms “asylum” and “lunatic.” Between 1808 and 1930, a series of remarkable directors led to the initiation of research and teaching that was unequaled in Britain. A museum of the era has been established in the hospital, now called Stanley Royd Hospital. A full account of the history and characters has been written by A.L. Ashworth in

Stanley Royd Hospital, Wakefield, One Hundred and Fifty Years: A History (London, Berrico Publicity Co., 1975), and the following is a précis of that account.

The first Director, William Ellis, was destined to achieve the first accolade for “Services to the Insane.” Sir William's distinction was conferred on account of his insistence on the essential humanity of the insane patients in his charge at a time when they were considered little different to beasts as a result of misunderstanding and fear. In 1866, James Crichton Browne took up the directorship. He also received the accolade in an era before psychiatry became accepted as an aspect of medical science. Sir James attracted people to study in the asylum and instituted the first pathological laboratory in a mental hospital in Britain. The burgeoning of research was reflected in the in-house journal, The West Riding Lunatic Asylum Medical Reports, edited by Sir James with the assistance of the neurologist Hughlings Jackson, the neuropathologist Sir David Ferrier, and another asylum director, Dr. Bucknill. The Reports contain a remarkable series of observations, and when he retired from the directorship Sir James encouraged the editorial group to remain with him and founded the present-day journal Brain. Lord Adrian, in a comment on these personalities in 1939 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, recalled “a classical period in the history of medicine, the period when neurology became a science” (volume 126, pages 433–448). It was Crichton Browne who attracted Darwin to the asylum at Wakefield to conduct observations for his work The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals.

The asylum at Wakefield attracted such neuropathologists as William Bevan Lewis, who later took on the directorship of the asylum. He wrote one of the early British texts of psychiatry, characterized by a neurohistological slant, understandable at a time when a large proportion of patients in asylums suffered from neurological disease, especially general paralysis.

The last of the directors, before that designation was abandoned, was Prof. Shaw Bolton, whose presidential address to the Medico-Psychological Association describing the evolution of the hospital at Wakefield was published in the Journal of Mental Science, the forerunner of the British Journal of Psychiatry, in 1928 (volume 74, pages 587–633).