Depression is a common problem among older patients hospitalized with medical illness. While the rate of major depression in community-dwelling older adults is less than 1% (

1), it rises to above 10% in medically ill hospitalized elders (

2). Including subsyndromal depression increases the percentage of elderly patients with depressive disorders to 35% or more (

3). Many of these depressions are not transient and persist long after treatment of the medical illness and discharge from the hospital. Follow-up of depressed medical patients has shown that one-half to two-thirds continue to experience substantial depression at least 3 months after hospital discharge (

4,

5). Besides reducing quality of life, depressive disorder appears to delay recovery from physical illness (

6,

7), increase length of hospital stay (

8,

9), and increase mortality (

8,

10).

Despite depression's effects on morbidity and mortality, only a few studies have examined demographic, psychosocial, or health factors that influence changes in mood state over time in medical patients (

4,

11). These studies have shown that severe medical illness, greater functional impairment, and poorer cognitive status are associated with persistent depressive symptoms, although no consistent predictors of outcome have been identified. A majority of these depressions, no doubt, result from difficulties older persons have adjusting to the discomfort, physical disability, and loss of control caused by their medical conditions. While coping resources such as social support or religion might facilitate such adaptation, their effects on recovery from depression in medical patients have been largely ignored—despite evidence suggesting their potential importance (

12–

14).

There has been increasing interest in the effects of religious belief and activity on mental health (

15), particularly in regard to depression (

16). Studies of elderly medical patients have shown that a substantial proportion (more than 50%) use religious belief or activity to cope with the stress of physical illness, and these patients appear less depressed than those who do not rely on religion (

14,

17). Although the exact mechanism is uncertain, religious beliefs may provide a world view in which medical illness, suffering, and death can be better understood and accepted. Alternatively, they may provide a basis for self-esteem that is more resilient than sources that decline with increasing age and worsening health. To our knowledge, however, no study of either medical or psychiatric patients has examined the impact of religious factors on the course of depression.

This report comes out of a larger ongoing study of the diagnosis, course, and impact of depression in the medically ill elderly. Here we examined the effects of religious beliefs (intrinsic religiosity) and activities (prayer and Bible reading, church attendance) on time to remission from depression. We hypothesized that after the usual predictors of depression outcome, including change in physical functioning, were controlled for, these religious factors would be associated with a shorter time to remission.

DISCUSSION

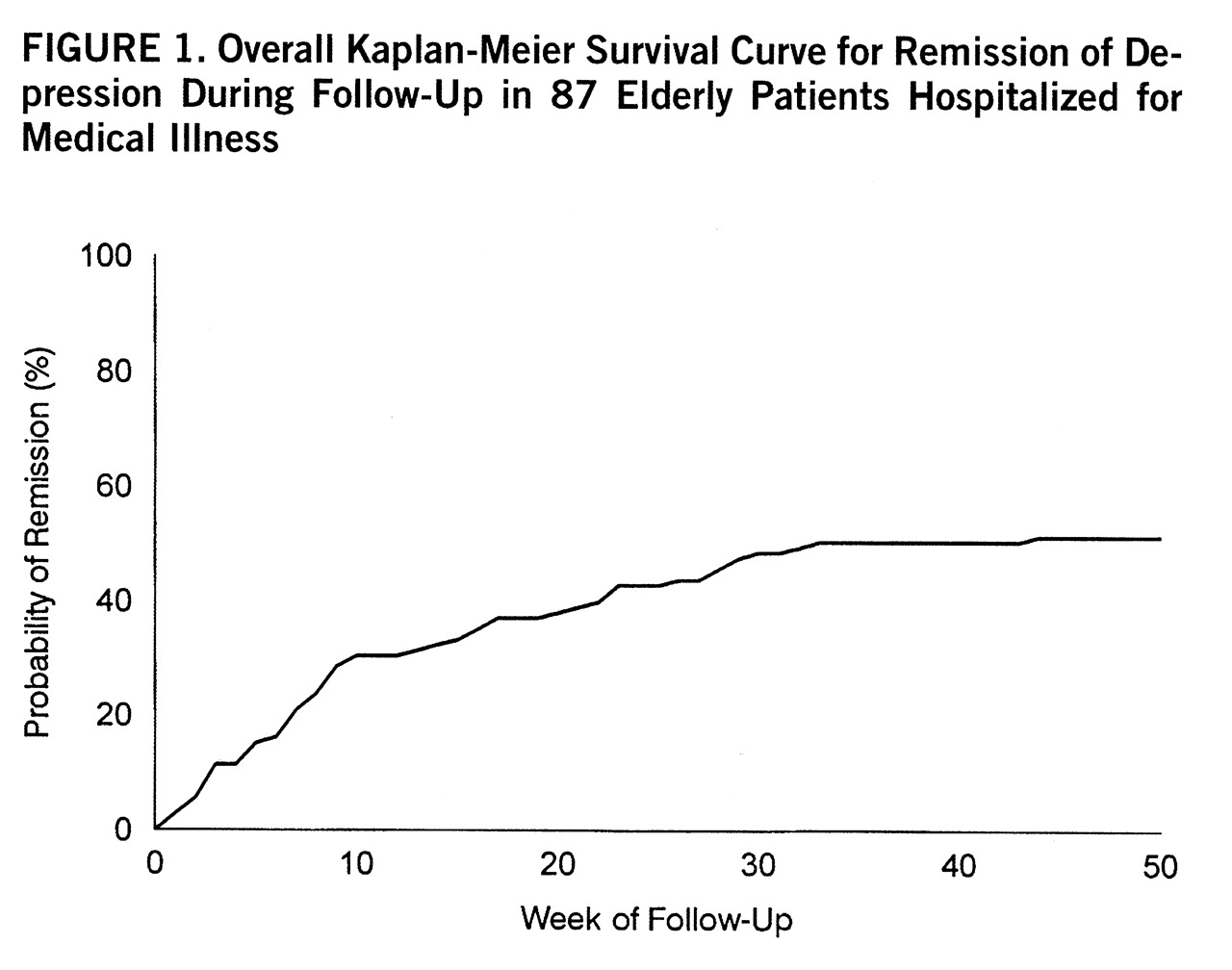

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to examine the effects of religiosity on depression outcome. Depressed older adults hospitalized with medical illness were identified, and the course of their depressive disorders was tracked for almost a year. A little over one-half of these patients went into full remission during this period, many (almost 50%) without any formal treatment for their depression. On the basis of prior studies, we hypothesized that religious factors might play a role in the remission of depression in this population.

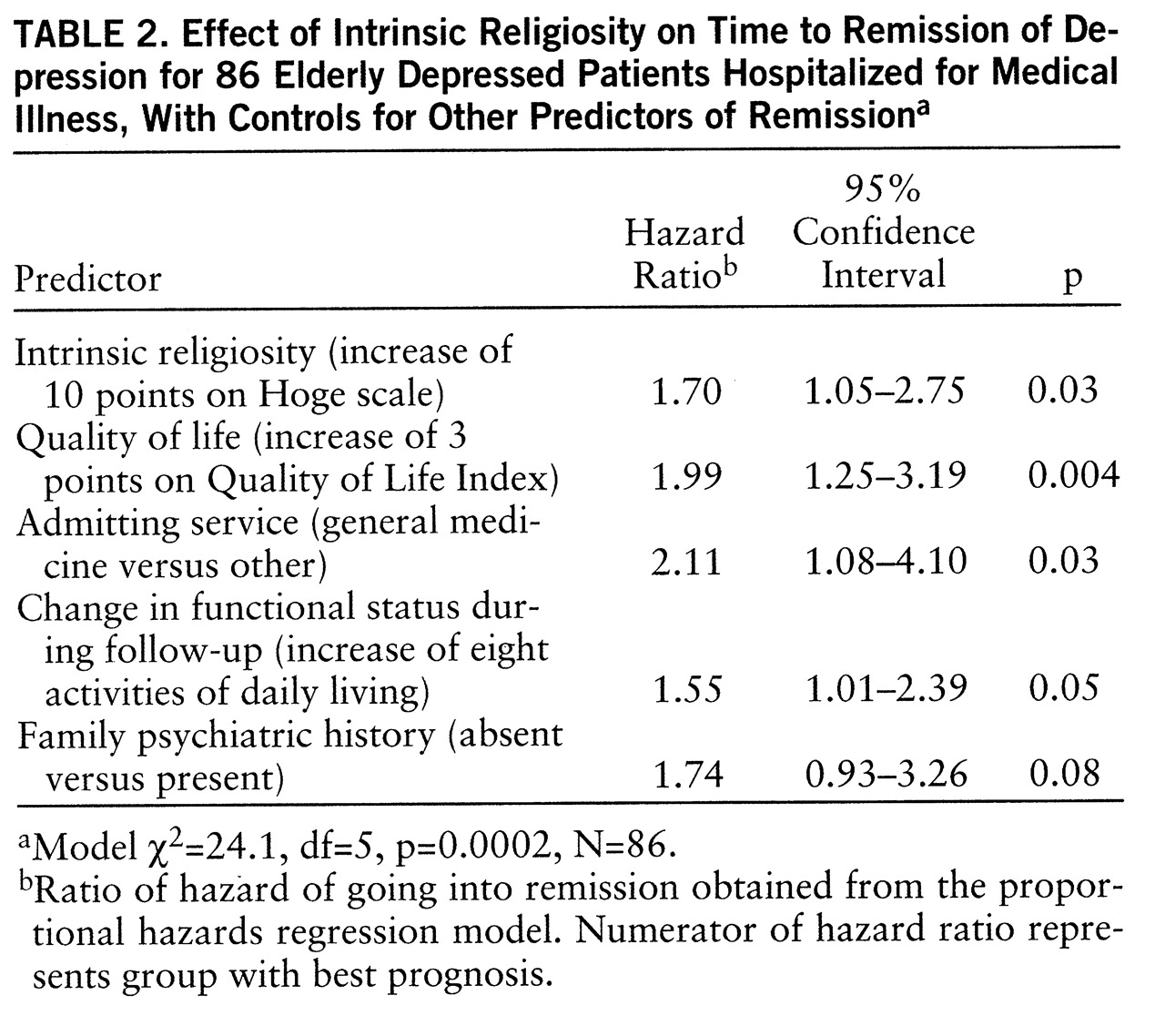

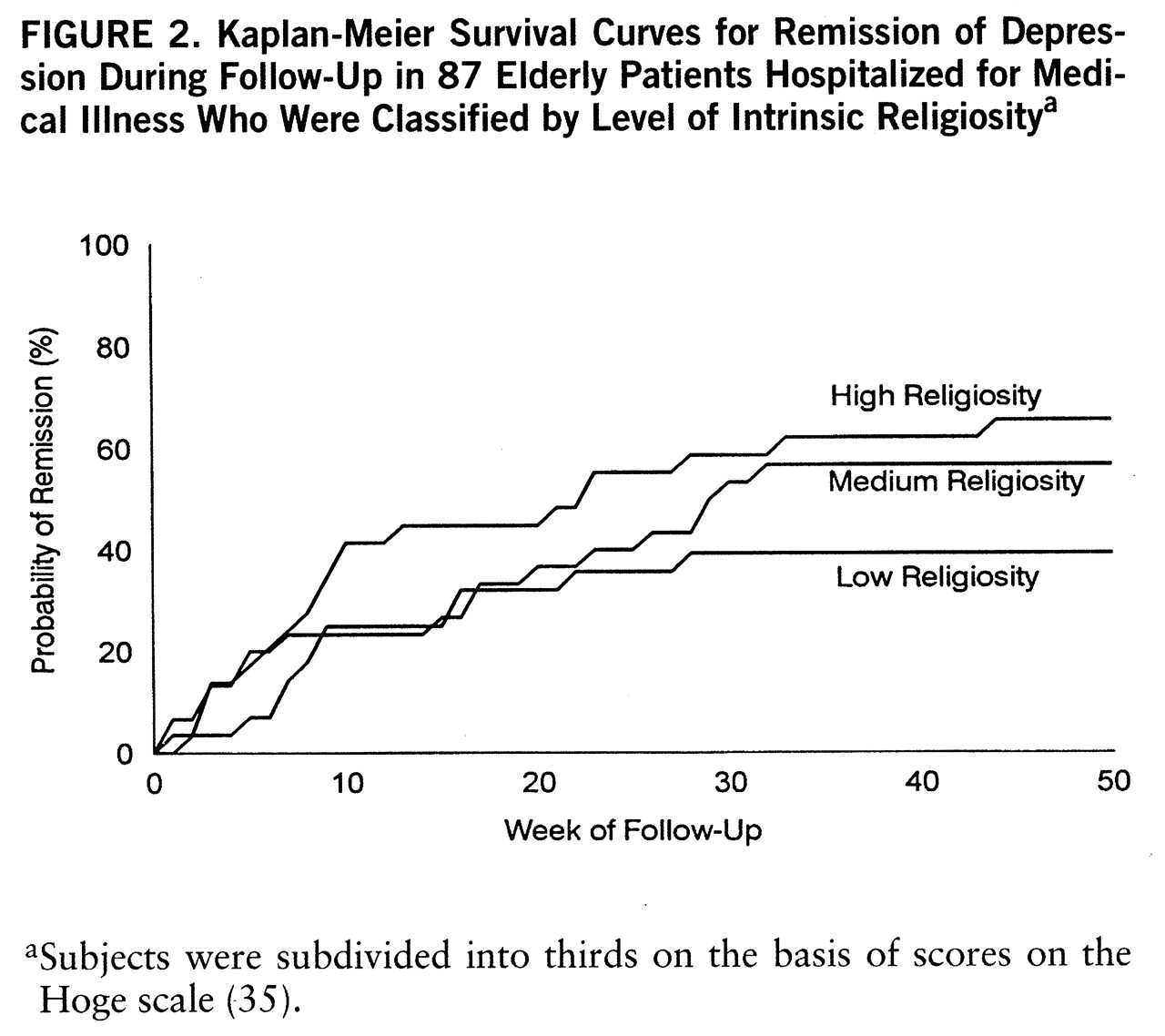

Intrinsic religiosity did predict shorter time to remission, an effect that persisted after we controlled for multiple demographic, psychosocial, physical health, and treatment factors. For every 10-point increase in intrinsic religiosity score, there was a 70% increase in the speed of remission. There was no evidence that this effect was due to religious persons being less likely to report depressive symptoms. While the effects were in the expected direction, neither church attendance nor private religious activities significantly predicted faster resolution of depression. This was true despite the fact that both church attendance and private religious activities were strongly related to intrinsic religiosity (Pearson r=0.39 and r=0.44, respectively, N=87, p<0.0005).

Might confounding explain this association? While it is possible that some unmeasured variable related to both intrinsic religiosity and faster remission of depression might explain this association, it is unlikely, given that we measured and controlled for almost all known predictors of depression course. What about biased outcome assessments? Research assistants doing the telephone follow-up evaluations were blind to the study hypotheses and were largely blind to the religiosity of patients, which was assessed only once (in the midst of a 1–2-hour baseline interview) and never examined again.

What about a chance association? A major research question in 1993, when this study was initiated, was whether or not religiousness predicted faster remission of depression. This was of particular interest because we had found in an earlier study of 850 hospitalized veterans that religious coping was inversely related to depressive symptoms both at baseline and on follow-up (202 patients followed an average of 6 months). In that study, the religious variable accounted for 45% of the explained variance in follow-up depression scores (

14).

Finally, as part of the current study, we asked the 87 depressed patients at study entry an open-ended question about what they thought enabled them to cope with the stress of their physical illness and other depressing things in their lives. One-third (32.6%, 28 of 86) spontaneously and without prompting gave religious responses (“God,” “the Lord,” “my faith,” “prayer,” “Jesus,” and so forth). All patients were then asked to rate on a 0 to 10 scale the extent to which they used religion to help them to cope with their condition; almost two-thirds (63.5%, 54 of 85) indicated 7.5 (“a large extent”) or higher. Thus, before any outcome assessments, we were told by patients that religion was an important factor that enabled them to cope. This supports the credibility of the finding that higher intrinsic religiosity predicted faster remission of depression and argues against it being due to confounding, chance, or bias of study investigators.

While this may be the first report on religion's effects on the course of depression, it is not the first time that investigators have examined the relationship between intrinsic religiosity and depression in older adults. Three (

42–

44) of four such studies showed a significant inverse relationship between these variables, with an average uncontrolled correlation of r=–0.27; they also showed significant associations with high self-esteem, with uncontrolled correlations averaging r=0.34. The fourth study of bereaved elders (

45) indicated no relationship between depression and intrinsic religiosity, but there was a significant positive association between depression and

extrinsic religiosity. Other studies have examined relationships between intrinsic religiosity and variables such as well-being (

46) and internal locus of control (

47); in both studies there were significant and positive correlations. Allport and Ross (

48) described the intrinsically religious person as follows:

Persons with this orientation find their master motive in religion. Other needs, strong as they may be, are regarded as of less ultimate significance, and they are, so far as possible, brought into harmony with the religious beliefs and prescriptions. Having embraced a creed, the individual endeavors to internalize it and follow it fully. It is in this sense that he lives his religion. (p. 434)

Thus, intrinsic religiosity, while related to church going and frequency of private religious activities, is not the same. Neither of these religious activities measures the extent to which religion is the master, motivating factor in peoples' lives that drives their behavior and decision making. Furthermore, unlike church attendance, intrinsic religiosity is not limited by health problems, which may even increase it.

Older persons with an intrinsically motivated religious faith may indeed be more able to cope with changes in their physical health and living circumstances because their self-esteem and sense of well-being are not as tied to either their ability to produce or their material circumstances. As these latter resources diminish with increasing health problems and disability, religious beliefs and cognitions may remain little affected. In this study we found that intrinsic religiosity was a particularly strong predictor of time to remission in patients whose physical functioning since hospitalization had either worsened or improved only minimally. Religious faith may provide such persons with a sense of hope that things will turn out all right regardless of their problems and, thus, foster greater motivation to achieve emotional recovery.

Treatment had no effect on depression outcome, regardless of whether patients had major depression or subsyndromal depression. Such a finding is not surprising and is likely due to 1) the case mix of patients in a naturalistic study (some who had recently begun treatment, others having been treated for many months) and 2) inadequate treatment by nonpsychiatrists (subthera~peutic doses of tricyclics such amitriptyline, excessive doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, short duration of treatment due to discontinuation, and lack of follow-up or dose monitoring) (

38).

The results of this study should be generalized with caution for several reasons. First, our study group was unique in that it consisted of patients hospitalized for medical problems who had relatively mild depressions. These results may not necessarily generalize to depressed older adults seen for treatment in psychiatric settings or to those with melancholic or more severe depressions. Second, this study took place in the Bible Belt region of the United States, where religion is deeply ingrained in the culture and social fabric of society. A comparison of the religious characteristics of our study group with those of older adults in the overall United States, however, shows smaller differences than one might expect. For example, 45% of our study group reported attending church weekly or more often, compared with 53% of older adults nationally (

49). Likewise, 63% of our study group said they spent time in prayer, meditation, or Bible study once a day or more, compared with 95% of older Americans who say they pray (

50) and 59% who read the Bible three or more times per week (

51). The religious activity of our study group, then, is consistent with the high degree of religious activity among older Americans in general.

Religious beliefs and behaviors are commonly used by depressed older adults to cope with medical problems and may lead to faster resolution of some types of depression. Psychiatrists should feel free to inquire about and support the healthy religious beliefs and activities of older patients with disabling physical health problems, realizing that these beliefs may bring comfort and facilitate coping.