Subjects

Demographic characteristics. Data were available for all 187 elderly patients entered into the Pittsburgh study of maintenance therapies in late-life depression protocol from its inception on Feb. 1, 1989, to the close of intake 7 years later on Jan. 31, 1996 (intent-to-treat sample); 687 patients were screened to yield the final sample of 187. The major reasons for exclusion were 1) other psychiatric diagnosis (N=135); 2) major depressive disorder, single episode (N=119); 3) interepisode wellness interval greater than 2.5 years (N=63); 4) medical contraindications to use of nortriptyline (N=43); and 5) presence of delusional (N=24) or intermittent (N=23) depressive disorders. Patients meeting eligibility criteria entered the study after providing written informed consent following full explanation of procedures.

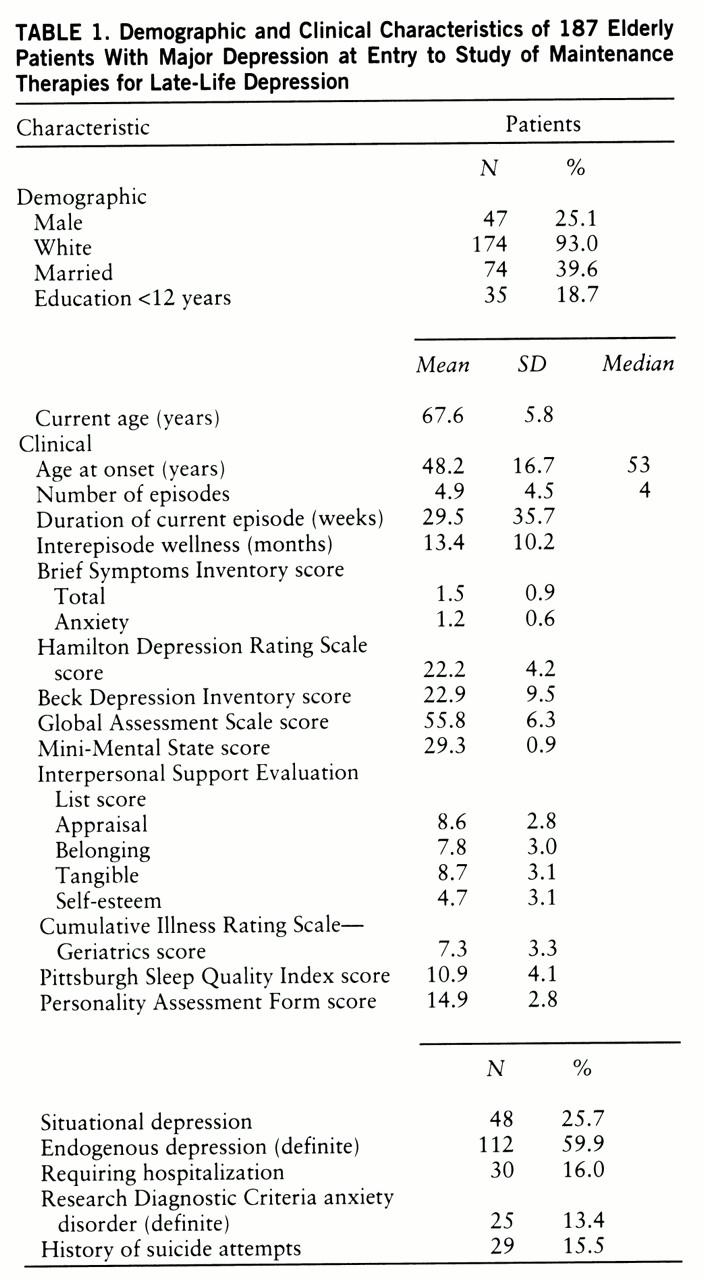

Demographic and clinical measures of the final study group are summarized in

table 1. To be consistent with other reports in the literature (

2,

4), we grouped patients by early versus late age at onset. Early onset was defined a priori as having a first lifetime episode of major depression at age 59 or earlier; late onset was defined as age 60 or later. All patients were required to have recurrent unipolar major depression (nonpsychotic), as determined by structured interview with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (

10). A score of 17 or higher on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

11) and a score of 27 or greater on the Folstein Mini-Mental State (

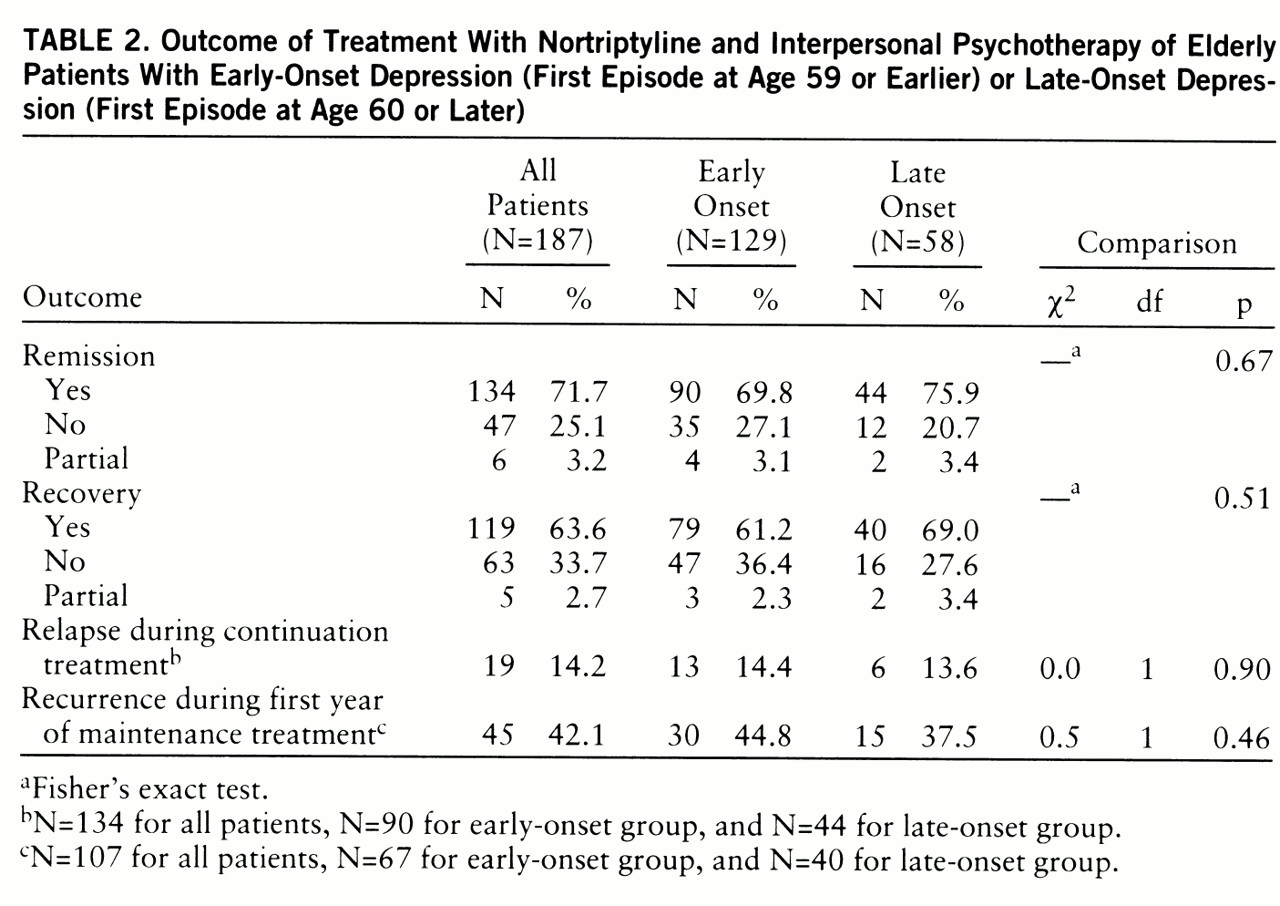

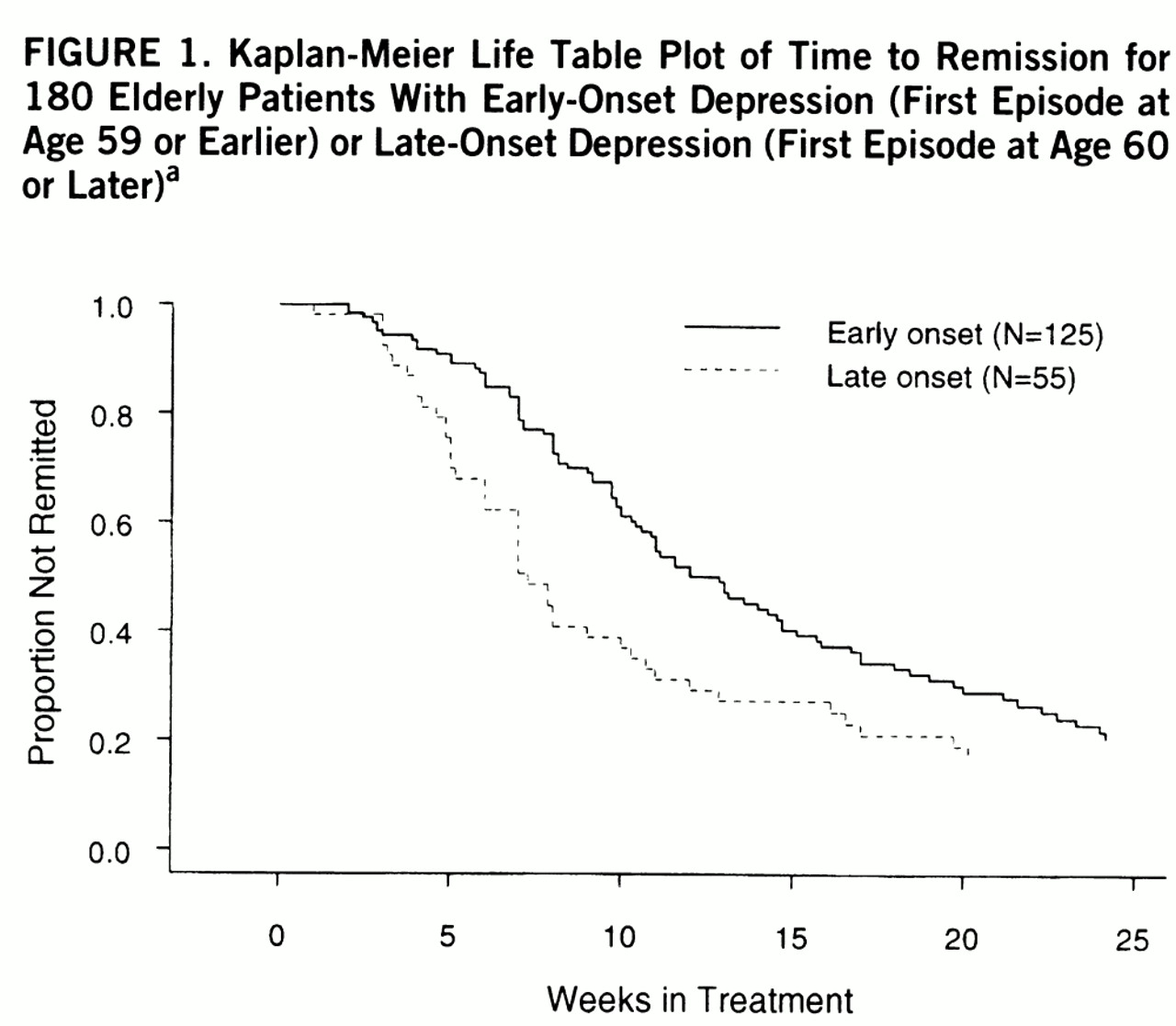

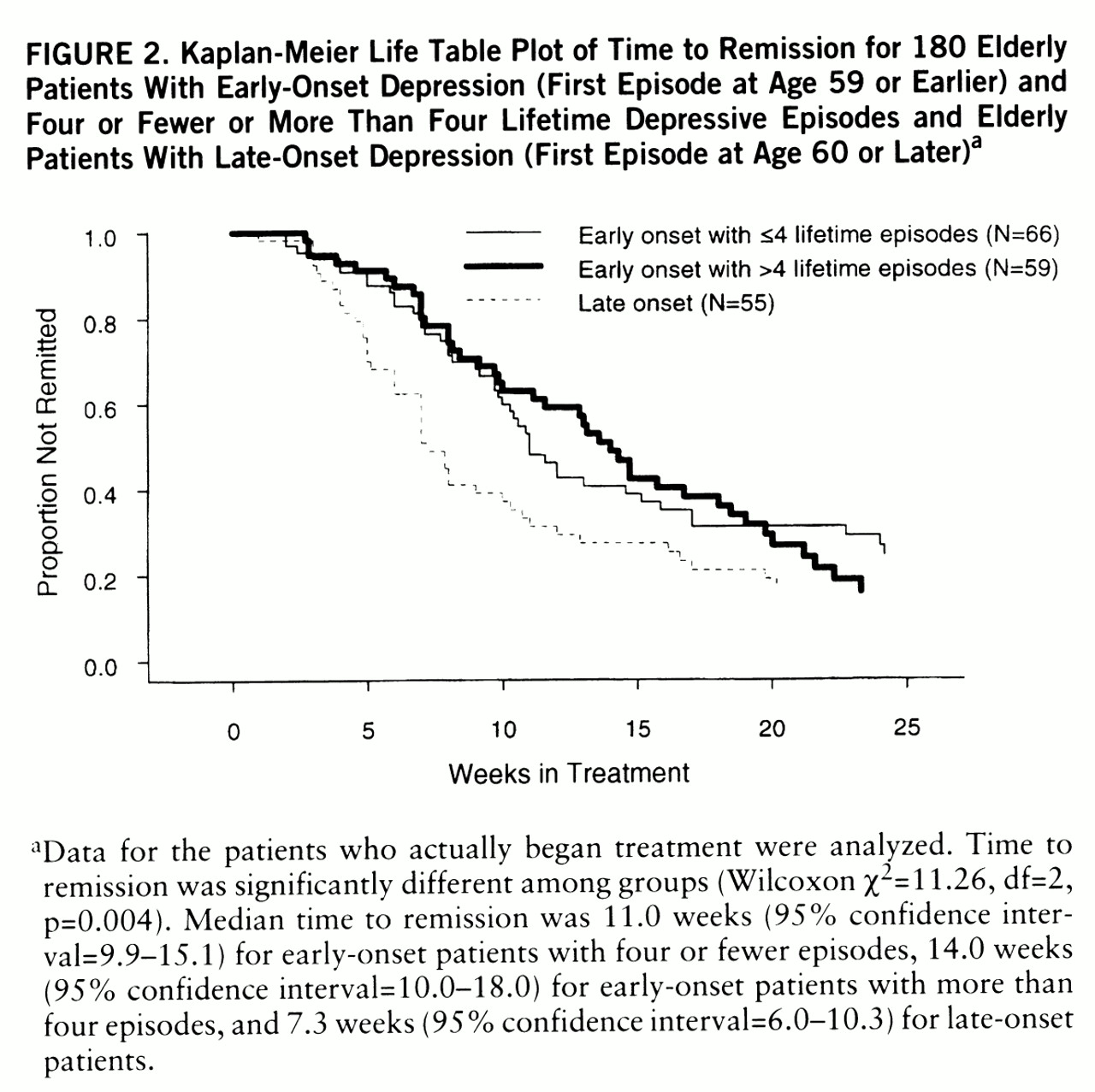

12) were also required for study entry. There were 129 patients in the early-onset group and 58 in the late-onset group. The late-onset group were on average 3 years older than the early-onset group at study entry (mean=69.6, SD=5.8, versus mean=66.7, SD=5.6) (t=–3.2, df=185, p=0.002). The groups did not differ in sex, race, marital status, or years of education.

Clinical characteristics. The groups also were similar on most clinical characteristics, such as severity of current episode, percent who required hospitalization during acute treatment, percent with endogenous episodes, duration of episodes, length of wellness interval before the index episode, functional impairment, percent with lifetime histories of anxiety disorders, chronic medical illness burden, personality dysfunction, perceived interpersonal support, and self-reported sleep quality. With respect to specific organ system scores on the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics (

13), late-onset patients scored significantly higher on the measure of systemic vascular impairment (mean=1.2, SD=1.1, versus mean=0.8, SD=1.0) (t=–2.6, df=170, p=0.01) but lower on focal neurological impairment (mean=0.2, SD=0.6, versus mean=0.5, SD=0.8) (t=2.6, df=141, p=0.01).

By design, the groups differed in age at onset of first lifetime episode, with a group difference of 26 years: mean=40.2 (SD=13.4) versus mean=66.0 (SD=5.9) (t=–18.2, df=185, p=0.0001). Not surprisingly, early-onset patients reported a greater number of lifetime episodes of major depression: mean=5.8 (SD=5.1) versus mean=2.7 (SD=1.3) (t=6.5, df=160.9, p=0.0001). Therefore, we chose to use number of lifetime episodes (as well as age at study entry) as a covariate in the Cox proportional hazards model of time to remission to determine if any difference observed as a function of age at first illness onset remained after we controlled for difference in number of episodes and age at study entry. Finally, a higher proportion of early-onset patients reported a history of suicide attempts (22.5% [N=29] versus 1.7% [N=1]) (p=0.0006, Fisher's exact test).

Treatments

All subjects received nortriptyline ti~trated to plasma steady-state levels of 80–120 ng/ml. Final plasma nortriptyline steady-state levels did not differ between early-onset (mean=91.4 ng/ml, SD=26.1) and late-onset (mean=86.5 ng/ml, SD=24.8) groups (t=0.9, df=117, n.s.), but a significantly higher dose of nortriptyline was needed in the early-onset group (mean=84.6 mg/day, SD=34.9) than in the late-onset group (mean=67.0 mg/day, SD=22.9) (t=2.8, df=117, p=0.007), probably reflecting age-dependent differences in metabolic rate. (The early-onset group was younger at study entry than the late-onset group.) However, the groups did not differ in the time required to reach the 80 ng/ml threshold concentration, nor in the percentage who received adjunctive psy~chotropic medications. Thus, pharmaco~logical parity was achieved in the treatment of the two groups.

Similarly, all patients participated in weekly interpersonal psychotherapy for at least 12 consecutive weeks (

8). The groups did not differ in the distribution of primary foci of interpersonal psychotherapy, such as bereavement, interpersonal conflict, or role transitions.

Definition of Primary Treatment Outcomes

With respect to the primary treatment outcome measures, we followed the convention of Frank et al. (

14) for defining remission, recovery, relapse (during continuation therapy), and recurrence (during the first year of maintenance therapy). Specifically, after patients achieved a Hamilton depression score of 10 or less for 3 consecutive weeks, their index episodes were declared to be remitted. Patients with “partial” remission (N=6) were defined by a Hamilton score of 11–14 at the end of acute therapy. We chose a Hamilton score of 10 or less as the criterion for remission in order to be consistent with the geriatric literature (e.g., Georgotas et al. [15]; Frank et al. [14] used a score of 7 in midlife studies). A 16-week period of continuation therapy began, during which patients continued to receive the same dose of nortriptyline used during acute therapy and every-other-week interpersonal psychotherapy.

After completing 16 weeks of continuation pharmacotherapy and interpersonal psychotherapy, patients were declared “recovered,” as long as they had not experienced relapses of their major depressive episodes. Of the 187 patients who entered the study, 124 recovered and were randomly assigned to maintenance therapy (nortriptyline with monthly maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy, nortriptyline in a medication clinic without interpersonal psychotherapy, placebo with monthly maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy, or placebo in a medication clinic without interpersonal psychotherapy). There was no significant difference in the distribution of random maintenance treatment assignments across the two groups (χ2=1.65, df=3, p=0.65). Patients were seen monthly during double-blind, placebo-controlled maintenance therapy to determine continued wellness or the recurrence of a major depressive episode, defined by using the SADS-L and confirmed by an independent senior psychiatrist.