In the increasingly competitive U.S. health care marketplace, health plans have a powerful incentive to enroll healthy individuals and to avoid individuals with potentially costly medical conditions (

1). “Adverse selection” of certain plans or types of plans by the sickest individuals may ultimately force those plans to raise premiums or to reduce benefit levels, promoting a spiral of increasing costs and decreasing choices for the remaining enrollees (

2). Thus, knowing whether and to what degree certain types of health plans attract sicker enrollees is a central issue for health care purchasers, plans, and consumers.

While authors generally agree about the detrimental effects of biased selection in health care, the literature has been notable for a lack of consensus about under which circumstances it occurs, or whether it even occurs at all. Although certain studies have shown that health maintenance organizations (HMOs) may enroll individuals who have previously used fewer medical services (

3), other authors have reported that differences in age may explain most of this apparent adverse selection (

4). A study using data from the 1992 National Health Interview Survey showed no difference in the proportion of enrollees with chronic illness between HMOs and indemnity plans (

5).

Authors have suggested that adverse selection may be of even more concern for mental health care than for general medical care (

6). Insurers' fear of overutilization of specialty mental health services, combined with a perception of relatively low overt consumer demand for such services, leads to more aggressive restriction of mental health than other health benefits. These processes may be accentuated for HMOs, in which restrictions on specialty care and limits on choice of providers are the central mechanisms of cost containment (

7). A Swiss study (

8) lent support to the potential importance of mental health factors in adverse selection, although its generalizability to U.S. managed care was limited by the small number of subjects and its location outside the United States.

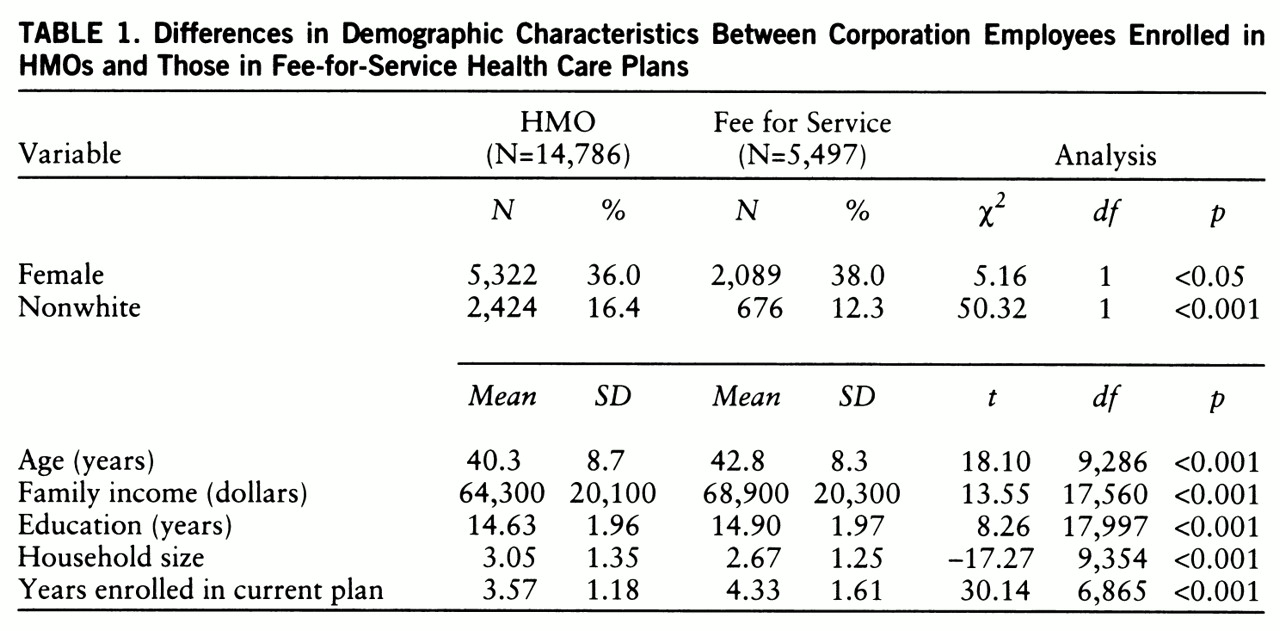

Thus, while there is reason to suspect that individuals with mental health symptoms may be hesitant to enroll in managed care plans because of such restrictions on benefits and limits on choice of providers, there are few empirical data on whether or to what degree it is the case. In this study we examined the relative contributions of physical symptoms and depressive symptoms to plan enrollment by using results from a 1993 survey covering employees across multiple geographic locations and health plans. The study investigated the hypothesis that symptomatic individuals, in particular those with depressive symptoms, disproportionately select fee-for-service plans for their care.

DISCUSSION

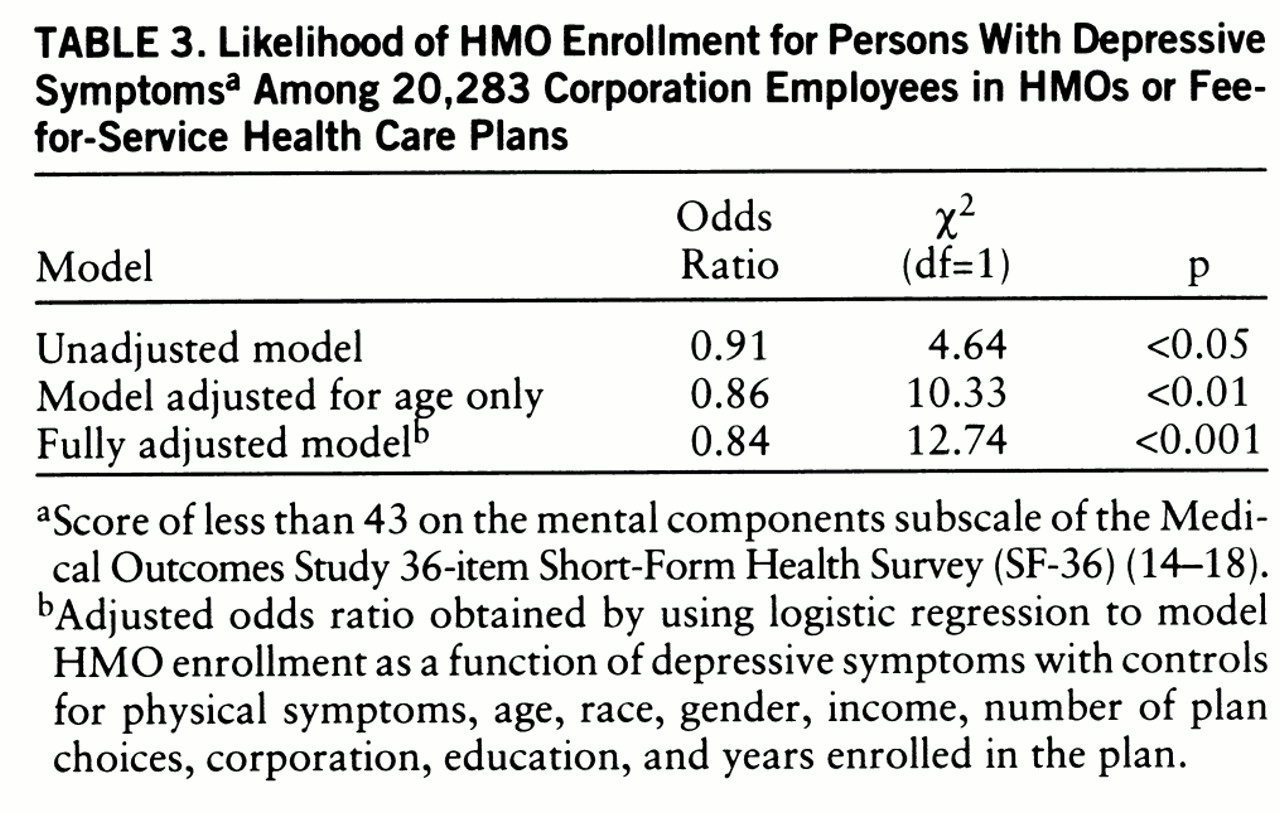

This study's findings support the hypothesis that symptomatic enrollees, in particular enrollees with psychological as opposed to somatic distress, are more likely to be enrolled in plans with a fee-for-service option than in HMOs. While authors have speculated that adverse selection may be of particular concern for individuals with mental disorders (

6), to our knowledge this is the first study to provide empirical evidence of a positive association between mental health symptoms and enrollment in fee-for-service care across a number of health plans and U.S. geographic regions.

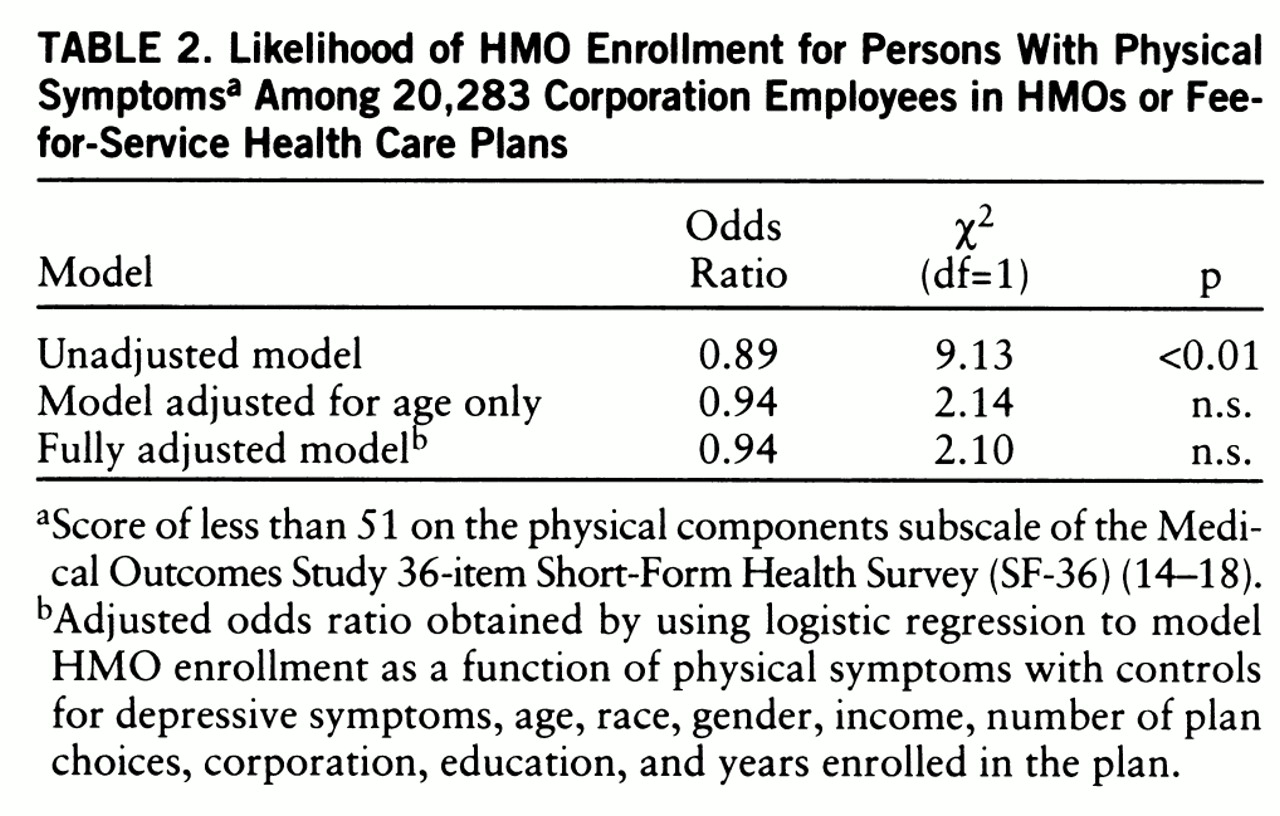

Physical symptoms were associated with fee-for-service enrollment in the unadjusted model but not in the adjusted models. Simply adjusting for age accounted for most of the effect of physical symptoms on fee-for-service enrollment. Because older enrollees tend to be sicker and more costly, and because age is a characteristic that is easy to determine from administrative data, plans typically adjust for this variable when setting premiums (

4).

However, the differences in depressive symptoms between plan types persisted after we controlled for demographic and plan-related variables. These findings indicate that fee-for-service plans may be treating a population with a “hidden” burden difficult to detect, and even more difficult to adjust for, by using the data typically available to employers or health plans.

Health plans, employers, and enrollees may each be playing a role in creating the unequal distribution of individuals with depressive symptoms between HMOs and fee-for-service plans (

25). In the absence of countervening incentives, plans may decide that restricting mental health benefits simultaneously saves costs incurred by current members and minimizes the plans' risk of attracting sicker, high-cost enrollees in the future. Previous studies have shown that HMOs provide less intensive mental health treatment for individuals with mental disorders than do traditional plans (

26), even after sociodemo~graphic and health status variables are controlled for (

27). Because of the high comorbidity of mental and medical disorders in general medical settings (

28), discouraging enrollment of individuals with depressive disorders may also serve to reduce the number of enrollees with chronic medical disorders.

Consumers with depressive symptoms may avoid HMOs because of restrictions on benefits or limitations on choice of providers. Individuals with established provider relationships (

29), especially users of mental health services (

30), have been found to be reluctant to switch to managed care plans that require them to disrupt those relationships. The desire to preserve the connection with their providers may make such individuals willing to pay the higher costs associated with fee-for-service plans. However, for enrollees with limited or fixed incomes, the ability to trade off cost for continuity of care may not be possible, and it ultimately may result in inadequate care.

Finally, employers select the panel of plans from which employees can choose, and they set the percentage of the premium of each plan that must be paid by the employee. A number of employers are seeking to shift employees into managed care plans by increasing payments for higher-cost fee-for-service plans (

31). If subgroups of the population are unable or reluctant to switch plans, then such initiatives will accelerate the rate of adverse selection.

Because we examined an employed population in this study, the results cannot necessarily be generalized to elderly, poor, or unemployed populations. However, employer-sponsored insurance is the predominant mode of coverage in the United States, providing 61% of insurance for the nonelderly U.S. population (

32). Spouses and dependents are frequently covered by employees' insurance and in this sample were more likely to be covered under HMOs, which had both more enrollees and a larger mean household size. Furthermore, as managed care moves forward in Medicare (

33) and Medicaid (

34), the same economic forces driving adverse selection in the private sector are taking hold in the public sector as well (

35,

36).

The survey design imposes three additional constraints on the conclusions that can be drawn from the findings. First, while an association clearly exists between depressive symptoms and fee-for-service enrollment, a prospective design would be necessary to more firmly establish the direction of causality. Second, satisfaction surveys are always subject to nonresponse bias, but this survey's response rate of 63.5% compares favorably to those in similar surveys, and recent studies have shown only minimal differences between responders and nonresponders to such satisfaction surveys (

37). Finally, the survey's summary health measures limit the ability to assess the distribution of specific physical or mental illnesses across plan type. Nonetheless, the relatively high sensitivity and specificity of the mental symptom measure for detecting clinical depression suggests that a substantial proportion of the differential mental health burden on fee-for-service plans results from depression, an illness that is at once costly to society and treatable (

38,

39). The “cost offset” literature suggests that recognition and prompt treatment of depression in general medical settings can result in reduced overall health care costs (

40,

41).

With the failure of initiatives to increase the federal government's role in regulating health care (

42,

43), market forces are progressively determining the shape of U.S. health care delivery. Undetected adverse selection can disrupt the effective functioning of a free market system; findings from this study suggest that such a process may be occurring for individuals with depressive symptoms. Further research, particularly using prospectively collected data, is required to better understand the scope and potential consequences of this problem.