Hurricane Katrina was one of the most devastating natural disasters in United States history. It resulted in more than 1,300 fatalities, the destruction of thousands of homes and businesses, and the disruption of entire neighborhoods and communities. More than 2.5 million people were displaced by the storm to neighboring states, the largest interstate migration of Americans since the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. The American Insurance Services Group has estimated that the storm cost approximately $75 billion, making it by far the costliest hurricane ever to strike the United States (1, 2).

From a public health perspective, Hurricane Katrina created a dual crisis, both through adverse effects on health and by destroying much of the local health care infrastructure available to treat those conditions (3–5). In the month after the hurricane, there were more than 7,500 reports of health-related events in New Orleans; at the same time, residents returning to New Orleans reported a range of difficulties in obtaining medications and other needed medical services (6). Many safety net providers, including 11 community federally funded health centers and the New Orleans Charity Hospital, closed because of damage from the storm (7, 8).

This study is the first to our knowledge to examine how this unprecedented natural disaster affected the receipt of general medical and mental care by affected individuals. It uses data from the Veterans Administration (VA), a national safety net provider that cares for enrollees with high rates of poverty and chronic illness (9). Because the VA documents comprehensive national information on service use for its enrollees, data from this system can provide an understanding of service use for patients displaced by the storm in a system with relatively few economic and administrative barriers to access.

Method

Data for this study were drawn from a national administrative database of all outpatient clinic visits nationally in the VA that includes service use, diagnostic, and demographic data. The study focused on VA facilities in two regions affected by the hurricane, Biloxi-Gulfport, Miss. (two divisions of the Gulf Coast Veterans Health Care System), and New Orleans, La. Both regions were under mandatory evacuation orders, and both experienced fatalities and extensive property destruction. Although the Gulfport facility, which included both inpatient and some outpatient services, was destroyed, the Biloxi facility continued to provide a full range of inpatient and outpatient services. In contrast, the main New Orleans facility was completely closed after the hurricane.

A cohort was defined to include all veterans with one or more outpatient visits to the New Orleans or Biloxi-Gulfport VA between June and August of 2005, the 3 months before the hurricane. Parallel cohorts were defined including veterans seen during June through August 2004 and June through August 2003. The use of general medical and mental health services nationally throughout the VA health system was tracked for two time intervals: September 1–30 and October 1 through December 31 for each of the years. Use was tracked overall and broken out for persons with one or more visits with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and/or substance use.

Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios comparing the proportion using services in 2005 with the corresponding proportion from the 2003–2004 cohorts, with adjustment for use of services in the baseline period (June through August), age, sex, race, VA service connection, and VA pension status; service connection and pension status provide priority access to VA services.

Results

No veterans from the New Orleans VA received services from that facility after the hurricane. During September, a total of 67.8% of those in the New Orleans cohort who used VA services received them from facilities within a 500-mile radius of New Orleans, and 33.2% obtained care from sites more than 500 miles away. Of the Biloxi-Gulfport cohort, 87.5% of the veterans using VA services obtained them from the Biloxi-Gulfport VA, with 6.8% treated at facilities within 500 miles of Biloxi-Gulfport and 5.7% obtaining services in facilities more than 500 miles away. This pattern of displacement was similar between veterans using general medical and mental health services.

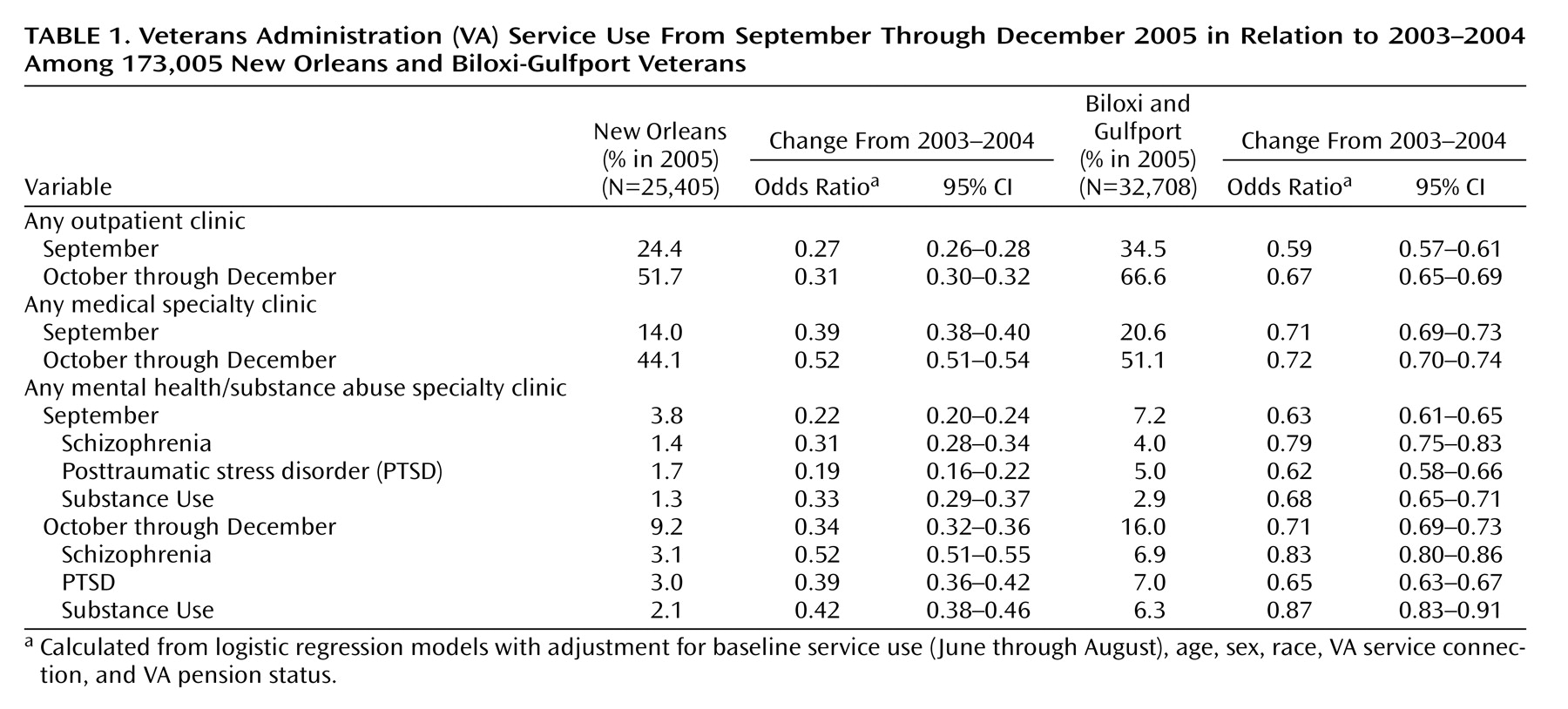

In multivariate models with adjustment for baseline use of services, age, sex, race, service connection, and pension status, veterans from the New Orleans facility were 73% less likely to use any outpatient services during September 2005 than their counterparts during 2003 and 2004 (odds ratio=0.27, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.26–0.28) (

Table 1 ). In Biloxi-Gulfport, veterans were 41% less likely (odds ratio=0.59, CI=0.57–0.61) than the cohort from 2003–2004 to use any outpatient services. These declines persisted but declined in magnitude during October through December of 2005.

The decrease in service use at the two facilities was more pronounced for mental health/substance use services (odds ratio=0.38, CI=0.36–0.40) than for general medical visits (odds ratio=0.55, CI=0.53–0.57). Among veterans from the New Orleans VA, the decline in likelihood of using mental health/substance use services during September (odds ratio=0.22, CI=0.20–0.24) was nearly twice as large as for general medical visits (odds ratio=0.39, CI=0.38–0.40) (

Table 1 ).

Among veterans using mental health and substance use services, the decline in services was most pronounced for veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD (

Table 1 ). For instance, during September of 2005, there was an 81% decline in the proportion of veterans with PTSD from the New Orleans VA using one or more mental health services (odds ratio=0.19, CI=0.16–0.22) compared with the previous year.

Discussion

The study found that there was a significant disruption in VA health services in the months following Hurricane Katrina. These effects were substantially more pronounced in New Orleans than in Biloxi-Gulfport, and they were also more apparent for mental health/substance use services than for general medical visits. Nonetheless, many individuals were able to obtain VA services within the period, and there was evidence of improving access by October through November of 2005.

The decline in access to services in Biloxi-Gulfport was only about half as large as that seen in New Orleans. Although both regions were under an evacuation order and both suffered extensive damage, the Biloxi facility remained open in the storm’s aftermath, and many veterans continued to receive services at that site. This finding speaks to the particular devastation brought about by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, where the health and social effects of the storm were compounded by large-scale destruction of the local health infrastructure and a lengthy evacuation.

The disproportionately rapid reduction in mental and substance abuse services in the months after the hurricane is of concern. In an October survey of residents of two New Orleans parishes, the Centers for Disease Control found high levels of emotional distress, with approximately one-third of the residents demonstrating a probable need for mental health care based on their symptoms (6). Persons with preexisting conditions and stressors may be particularly vulnerable to traumatic responses after large-scale traumatic events (10–13).

The decline in service use among veterans with PTSD is particularly troubling given the likely need for such specialized trauma services in the wake of a large-scale disaster. These findings reinforce studies reporting relatively low rates of mental health service use in the wake of the September 11 attacks (14, 15). In both cases, the relatively low rates of service use may reflect both challenges in obtaining access to services and patients’ preferences to seek help and support outside of the formal medical system. Although persons with preexisting PTSD may be particularly vulnerable to the reemergence of symptoms after a disaster, the specialized nature of PTSD services may make them more difficult to replace than other health and mental health services.

However, it is also reassuring that so many displaced veterans, particularly those with schizophrenia and substance use, were able to obtain mental health services at other VA facilities. There is anecdotal evidence that many individuals without insurance or receiving Medicaid faced enormous barriers to accessing services after the hurricane (3). The fact that veterans can access services at any other VA facility in the country likely makes this system a “best case” scenario for individuals displaced by the storm. The VA’s experience after Katrina demonstrates how a national integrated system can mobilize in response to a local disaster.

The study results should be interpreted in light of at least two limitations. First, the data did not capture use of non-VA services; although the formal medical system had limited capacity to absorb new patients in the aftermath of the storm, some displaced veterans may have obtained care outside of the VA through specialized programs such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Hurricane Assistance Project (5). Second, the study relied on administrative data and thus could not address key issues, such as the appropriateness or quality of care or potential adverse outcomes from nonreceipt of services.

These limitations notwithstanding, the study provides some of the first empirical evidence of Hurricane Katrina’s devastating impact on access to health and mental health services by individuals displaced by the storm. In the wake of this unprecedented natural disaster, it will be critical to rebuild and strengthen the health safety net both in areas affected by the recent hurricane and in communities at risk for similar damage in the future.