Antipsychotic-drug-induced weight gain has a number of meaningful clinical implications, especially in the long-term management of schizophrenia. In addition to its effect on general health risks, weight gain has a major impact on the subjective acceptance of these drugs and thus on compliance.

Substantial body weight gain occurs in up to 50% of patients during long-term antipsychotic treatment

(1). Second-generation antipsychotics can cause large increases in body weight; clozapine and olanzapine appear to cause the most weight gain, risperidone is associated with an intermediate gain, and ziprasidone is associated with less weight gain than haloperidol

(2–

4).

Olanzapine, like clozapine, has strong affinity to serotonin (5-HT) and histamine (H) receptors (5-HT

2C, 5-HT

2A, and H

1). There is strong evidence that blockade of these receptors is associated with weight gain

(2,

5–

8).

Clozapine and olanzapine have been shown to increase serum levels of leptin, a hormone exclusively expressed and secreted by differentiated adipocytes

(9). It acts as a feedback signal from the adipose tissue and may play a role in the pathophysiology of obesity. Leptin levels increase exponentially with body mass index or percentage of body fat, as determined by bioelectric impedance measurements

(9). The metabolic effects of leptin in vivo are suppression of food intake and stimulation of energy expenditure

(9).

To explore the pathophysiology of weight gain during antipsychotic treatment, we investigated weight, body mass index, percentage of body fat, change in eating behavior, and leptin serum levels in patients treated with olanzapine and in healthy comparison subjects. Studies that convincingly demonstrated the major impact of an increase in body fat and body mass index on mortality rates

(10–

12) add relevance to exploring this issue.

Method

Ten consecutively admitted inpatients who met the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia and who were assigned to monotherapy with olanzapine (dose range=7.5–20 mg/day) were included in the study. Five of the patients had received no other medication before olanzapine; five had received flupentixol, fluphenazine, risperidone, or haloperidol. All patients had been medication free for at least 3 days before olanzapine administration. Eight of the patients were men, and two were women. Their mean age was 30.4 years (SD=7.0). The mean observation time was 8.1 weeks. The comparison subjects were recruited from the hospital staff and were matched in age (mean=35.2, SD=5.1) and sex (eight men, two women). Patients and comparison subjects were not matched for diet, but subjects in both groups were on a stable diet before study entry. All patients gave written informed consent to participate in this study, which was performed according to the guidelines of the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of Innsbruck University.

Weight was assessed at baseline and weekly thereafter. All subjects were asked about their general eating behavior and habits at baseline. Every week patients and comparison subjects were asked about changes in their eating behavior by using a semistandardized structured interview that we devised. The questions included the following: What were you eating for breakfast, lunch, dinner? What are situations when you eat more or less than usual? The subjects were also asked if their eating behavior changed over the preceding week. They could choose among five options (ate much more, more, much less, less, and no changes).

Blood was obtained weekly from a peripheral vein after overnight fasting. Blood was centrifuged, and sera were analyzed immediately or stored at –80°C. Leptin concentration was determined by radioimmunoassay by using an antiserum that does not cross-react with human insulin, proinsulin, rat insulin, C-peptide, glucagon, pancreatic propeptide, or somatostatin (Linco Research, St. Charles, Mo.). According to the manufacturers’ instructions, the detection range is 0.5 ng/ml to 100 ng/ml. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation in the concentration range observed were less than 4% and less than 6%, respectively.

Body composition was determined every 4 weeks by impedance analysis with a multifrequency bioelectric impedance 2000-M analyzer (Data Input, Hofheim, Germany). Silver/silver chloride electrodes were placed on the skin of the right ankle and on the right wrist, and resistance and reactance were measured at 1, 5, 50, and 100 kHz, respectively. Measurements were taken after a fasting period of at least 8 hours. Fat-free mass and fat mass were determined by using Nutri 4 software (Data Input).

We hypothesized that olanzapine-induced weight gain would be accompanied by an increase in leptin serum levels and that an increase of body fat would be responsible for these findings.

A paired t test was used for within-group comparisons (week 8 versus baseline). A t test for independent samples was performed for between-group comparisons with respect to changes in all investigated measures between baseline and week 8.

Results

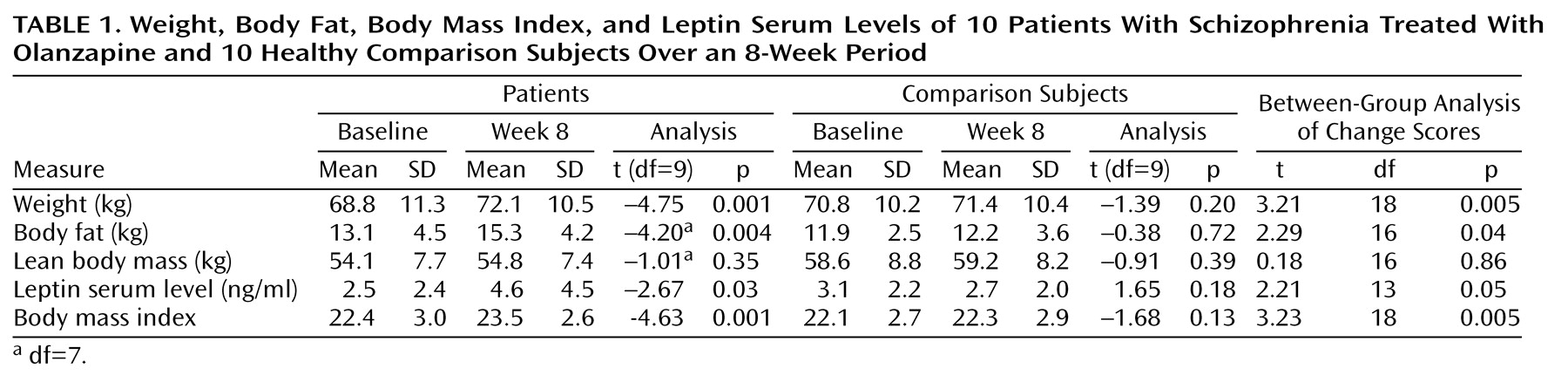

Patients gained a mean of 3.3 kg (SD=2.2) during an average treatment course of 8.1 weeks, a highly significant increase (

Table 1). The minimum weight gain was 1.2 kg, and the maximum was 6.5 kg. This weight gain was found to be mainly attributable to a significant increase in body fat: patients gained a mean of 2.2 kg body fat (SD=2.2) (

Table 1). The minimum gain in body fat was 0.5 kg, and the maximum was 5.0 kg. Only one of the patients (whose previous treatment was haloperidol) reported weight gain while taking haloperidol many years ago. He had normal weight at study entry and gained 3.5 kg over the 8-week period. When being rated weekly for changes in their eating behavior, seven patients reported at least one period with increased ingestion of food during the study.

Leptin serum levels increased significantly during olanzapine treatment (

Table 1). In nine patients serum levels increased two- to three-fold over time. Only one patient (the man who before the study had gained weight while taking haloperidol) showed no change in serum leptin levels, in spite of the fact that he gained body weight (3.5 kg) and his body fat increased (1.1 kg).

No significant changes in body weight, body fat, or leptin serum levels were seen in comparison subjects. The change scores (value at week 8 minus baseline value) differed significantly between groups in all of the investigated variables except lean body mass (

Table 1).

Discussion

Nine of 10 patients with schizophrenia gained weight during an average treatment time of 8 weeks with olanzapine monotherapy. This finding is in accordance with those of other studies

(4,

13,

14). In their meta-analysis of 78 studies, Allison et al.

(4) reported an estimated weight gain of 4.15 kg during 10 weeks of olanzapine treatment. Kraus et al.

(13) observed a mean increase of 3.9 kg during 4 weeks of treatment with olanzapine. Our patients, who gained a mean of 3.3 kg, fit this picture very well. The one patient who did not gain weight during the observation period received olanzapine in a dose of 15 mg/day. His body fat increased and leptin serum levels rose twofold while he lost lean body mass.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate body composition in the context of antipsychotic-induced weight gain. A number of authors

(10–

12) have shown that body fat increase is a determining factor of weight-gain-associated mortality. When analyzing body composition by body impedance analysis at baseline and after an average treatment time of 8 weeks, we were able to show that the observed weight gain in our group of patients was mainly attributable to an increase in body fat and not to an increase in body water content.

Seven of 10 patients reported increasing their ingestion of food at least at one rating, but no consistent time-course could be found. This finding is comparable to that of Brömel et al.

(15), who found that nine of 12 patients reported increased appetite during clozapine therapy. Increased caloric intake without more physical activity results in more body fat. In our semistandardized interview patients were asked about their physical activity. No one reported increasing their physical activity during the observation period but seven patients reported at least one period with an increased food ingestion during the study.

During the 8-week observation period, leptin serum levels increased significantly over baseline levels. This was to be expected, since fat mass is the major determinant of circulating leptin concentration. In contrast to Considine et al.

(16), we were not able to demonstrate a significant correlation between body fat and leptin level increase. This is most likely because we studied 10 patients and Considine et al. studied 136 normal-weight subjects and 139 obese subjects. One must also keep in mind that there is a tremendous variability of leptin serum levels and that the observed increase of 2 ng/ml, although significant, is rather small. Kraus et al.

(13) found a significant increase of leptin serum levels amounting to 4 ng/ml in patients who gained weight during clozapine and olanzapine treatment. Whether such an increase is clinically meaningful is yet to be determined. Maybe one of the physiological roles of leptin is as an appetite-reducing feedback signal in the event of fat increase.

Despite a small study group, we could clearly confirm our hypothesis that olanzapine monotherapy is associated with significant weight gain and an increase in body fat. Both weight gain and increase in body fat were associated with a significant increase in serum leptin levels. These findings add a new dimension to the discussion about the pathophysiology of antipsychotic-induced weight gain, although the biochemical underpinnings of underlying changes in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism need to be elucidated in further studies. Not only does weight gain lead to aesthetic and compliance problems, this side effect has to be considered a substantial health risk for patients afflicted. A drug-induced increase in body fat is likely to be an additive factor to the higher mortality rates reported in patients with schizophrenia.

We join others in calling for regular monitoring of weight and weight-related laboratory measures in patients receiving olanzapine. In concordance with the International Diabetes Center recommendations, blood pressure should be checked at every visit, hemoglobin A(1c) every 3–6 months, and a lipid panel annually. Patients should also be encouraged to monitor and, if necessary, adjust their dietary habits and exercise regularly. Patients who develop symptoms related to disturbances in glucose or lipid metabolism should be switched to a drug with a lower propensity to induce such problems. In patients at high risk for weight gain or diabetes, one should initiate treatment with drugs having a lower risk to induce weight gain.