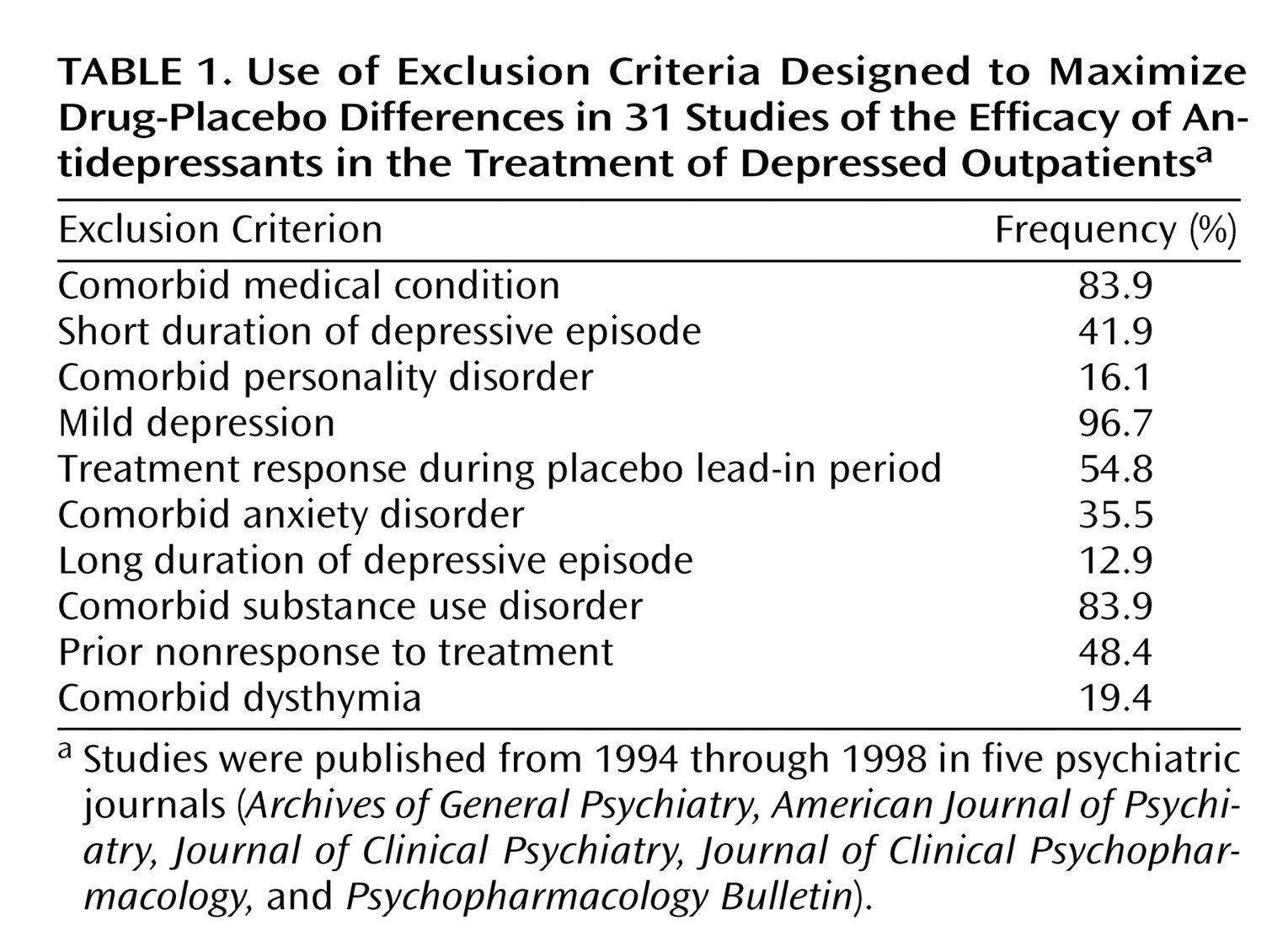

The primary aim of an antidepressant efficacy trial is to demonstrate drug-placebo differences. Consistent with this aim, antidepressant efficacy trials routinely exclude subjects believed to have high placebo response rates (e.g., subjects with mild depression) or low drug response rates (e.g., those with long-term depression or with comorbid anxiety, personality, or substance use disorders). The exclusion of these subjects significantly increases recruitment costs

(1) and limits the generalizability of antidepressant efficacy trials to a narrow population of “pure” depressed patients.

Few published accounts of antidepressant efficacy trials present the percentage of individuals applying for entry who are screened out. Partonen et al.

(2) reported that 381 of 612 subjects (62%) applying to participate in two separate antidepressant efficacy trials were excluded for a variety of reasons. Keitner et al.

(3) found that only 60 of 866 antidepressant efficacy trial applicants (7%) screened in telephone interviews were ultimately randomly assigned to treatment groups. A survey of 18 clinical trial investigators found that an estimated 80% of applicants to antidepressant efficacy trials overseen by the investigators were excluded

(1). Exact exclusion rates are difficult to determine, however, because eligibility is ascertained through a sequence of screening stages, and many ineligible subjects may not even be referred to such trials. We reported elsewhere that less than 15% of the depressed patients from our outpatient practice would be eligible to participate in an antidepressant efficacy trial due to various exclusion criteria

(4).

Considering the cost and the limits to generalizability associated with the exclusion criteria that have been employed in antidepressant efficacy trials, some researchers have begun to question the wisdom of their use

(5,

6). Since most exclusion criteria were implemented before rigorous testing, we wondered whether the current state of knowledge would support their continued use. The goal of the present report was to review the empirical research on the efficacy of antidepressant medications in subjects typically excluded from antidepressant efficacy trials. If comparable drug-placebo differences are found in these individuals, the standard exclusion criteria could perhaps be loosened without jeopardizing the overall aims of these studies.

Discussion

For years, investigators have raised concerns over the generalizability of antidepressant efficacy trials. Although some of the exclusion criteria used in antidepressant efficacy trials are clearly necessary, others are implemented primarily to maximize drug-placebo differences. This practice greatly reduces the generalizability of these studies but perhaps can be justified if it decreases the likelihood of obtaining a type II error, i.e., not finding drug-placebo differences when real differences are present. However, if drug-placebo differences are in fact no less robust in these populations, then the rationale for excluding these subjects becomes less tenable.

Three cohorts of subjects—those with mild depression, those with an episode duration of less than 4 weeks, and those who improve during the placebo lead-in period—are excluded to minimize placebo response rates. Although early studies suggested that subjects with mild depression may not respond any better to antidepressant medication than to placebo, these studies had several shortcomings, including a lack of statistical power in failing to reject the null hypothesis. More recent studies, though few in number, have shown that antidepressants may be efficacious for mild depression. Similarly, the practice of excluding placebo lead-in responders has never been shown to magnify drug-placebo differences, and all available evidence suggests that this exclusion criterion has no discernable impact on differential response rates. Although studies have consistently shown that a short episode duration is associated with high placebo response rates, a 3-month or less episode duration would appear to be a more empirically validated cutoff than 4 weeks.

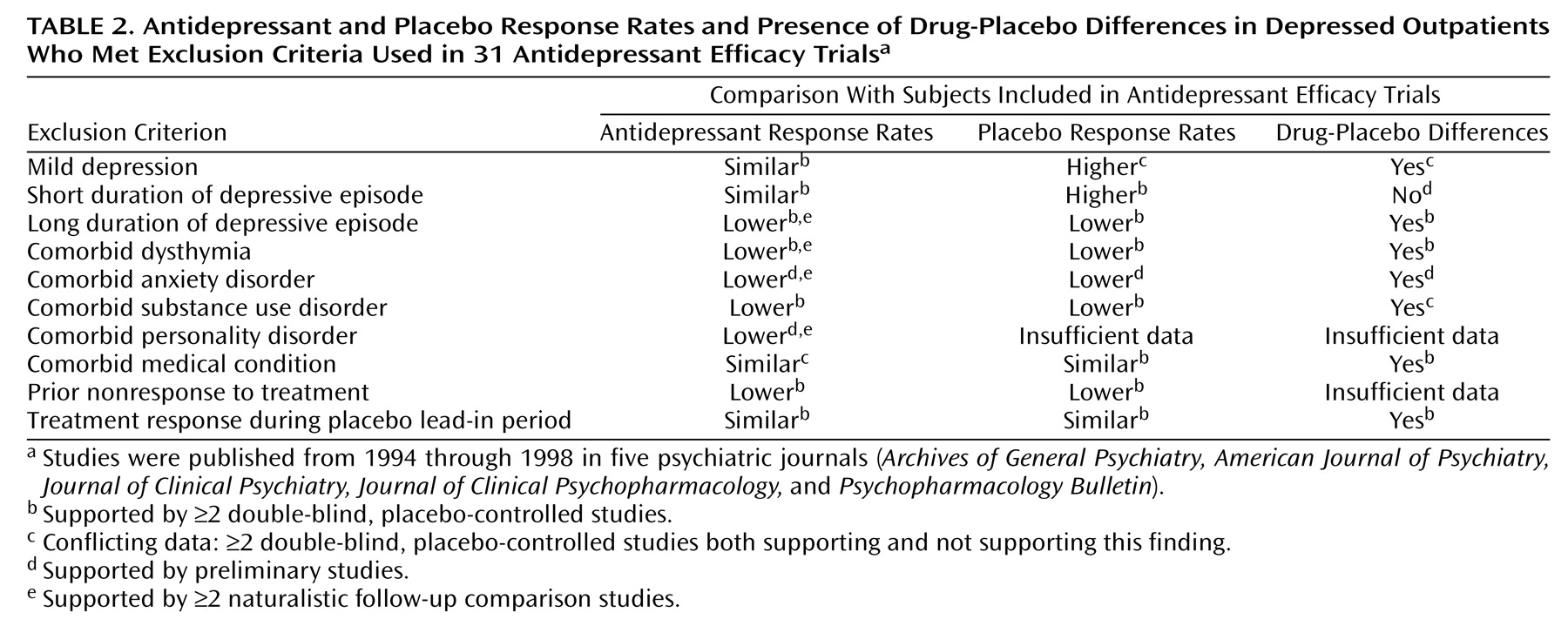

The remaining seven exclusion criteria that we reviewed—chronic depression, comorbid dysthymia, comorbid anxiety disorders, comorbid substance use disorders, comorbid personality disorders, comorbid medical conditions, and prior nonresponse to treatment—were originally implemented after naturalistic studies had shown that patients with these features responded less well to somatic therapy and had a worse overall prognosis. Without a placebo comparison group, however, a lack of drug-placebo differences cannot be inferred. Even now, few placebo-controlled studies have been performed to specifically address the efficacy of antidepressant medications in depressed patients with these features. The few studies that have been performed have suggested that placebo response rates are also lower in these patients.

In summary, our review suggests a paucity of empirical support justifying the use of the 10 exclusion criteria considered in the present report (

Table 2). For individuals with chronic depression, comorbid dysthymia, or medical comorbidity and for placebo lead-in responders, our review suggests that drug-placebo differences may be no less robust in these subjects than in individuals who qualify for antidepressant efficacy trials. For subjects with mild depression, a comorbid anxiety disorder, a comorbid substance use disorder, a comorbid personality disorder, or a history of nonresponse to treatment, the data are either conflicting or too preliminary to determine whether the magnitude of drug-placebo differences is any less. It remains unknown whether antidepressant medications are superior to placebo in patients with a short episode duration, but the high placebo and spontaneous response rates in these individuals make it likely that drug-placebo differences are significantly less robust.

Further evidence to support the efficacy of antidepressant medications in less rarefied populations is provided by placebo-controlled studies in primary care settings where standard exclusion criteria are not employed. Although only a handful of such studies have been performed with methods comparable to those in antidepressant efficacy trials, these studies have consistently found antidepressants to be efficacious in relatively unselected populations of depressed patients

(14,

58,

119,

125). Depressed patients in primary care settings have less psychiatric comorbidity and lower rates of treatment resistance than psychiatric patients, however, and these results can not necessarily be generalized to psychiatric patients.

In interpreting the results of the present review, several important caveats should be kept in mind. First, the review was limited by the scarcity of controlled studies involving the populations of interest. For example, it was our intention to statistically compare outcomes of subjects who are excluded from antidepressant efficacy trials with the outcomes of subjects who are typically included. However, the limited number of studies precluded any meaningful effect size comparisons. Second, although preliminary evidence has suggested that drug-placebo differences exist in many of the populations excluded from antidepressant efficacy trials, we do not know whether the magnitude of their response is comparable to that of those included in the trials. If the magnitude of drug-placebo differences were less in the excluded individuals, even if drug-placebo differences exist, then the exclusion of these individuals would still decrease the likelihood of obtaining a type II error. Third, our review includes only published studies and is therefore susceptible to the “file drawer” bias, since studies with negative results are less likely to be published. Because the number of placebo-controlled studies that have been performed in each of the populations reviewed here is small, only a handful of negative, unpublished studies would be needed to undermine our principal conclusions

(126). It should also be pointed that easing the inclusion/exclusion criteria of antidepressant efficacy trials would increase the heterogeneity of the population studied, and, therefore, the variance in base response rates would likely increase. When this occurs, the power to detect differences decreases. At this time, it is difficult to estimate the impact of this variance in base response rates on the results of antidepressant efficacy trials.

In conclusion, our review suggests that the rationale for employing many of the exclusion criteria used in standard antidepressant efficacy trials lacks a clear empirical basis. It is somewhat shocking that after 50 years following the introduction of antidepressant medications, there has yet to be a single published study that was designed specifically to evaluate their efficacy in depressed patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder or a comorbid personality disorder—patients who constitute perhaps that majority of those encountered in routine clinical practice. Other populations of patients, such as those with mild depression or chronic depression, have only rarely been the focus of systematic inquiry. Clearly, there is a need to move beyond the traditional model of how antidepressant efficacy trials are conducted.