Impairment in psychosocial functioning is integral to the concept of a personality disorder. Only when personality traits are sufficiently inflexible and maladaptive to cause significant functional impairment (or subjective distress) is normal personality style distinguished from a pathological personality disorder. DSM-IV codified a requirement for impairment in its criterion C of the general diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder, which states that “the enduring pattern [of inner experience and behavior, i.e., personality] leads to clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning” (p. 633).

Since 1980, when attention was focused on personality disorders by placing them on a separate diagnostic axis (axis II) of DSM-III’s multiaxial system, a number of studies have documented functional impairment in patients with personality disorders compared with patients with no personality disorder or with other axis I disorders. Most of these studies inferred functional impairment from various sociodemographic statuses believed to reflect psychosocial functioning, such as educational attainment, marital status, or employment. A majority of these studies found that patients with personality disorders were more likely than those without or with other disorders to be separated, divorced, or never married

(1–

11) and to have had more unemployment, frequent job changes, or periods of disability

(4,

5,

7,

9,

12,

13). Only rarely were they found to be less educated

(1,

12). Fewer studies have examined quality of functioning, but in those that have, poorer social functioning or interpersonal relations

(2,

4,

5,

7,

13–

18) and poorer work functioning or occupational satisfaction and achievement

(2,

4,

7,

14–

16,

19–

22) were found among patients with personality disorders compared with others. On measures of global functioning, most studies have shown significant global functional impairment for patients with personality disorders

(4,

5,

13–

15,

17–

19,

23–

33).

Other than the studies that have used the Global Assessment Scale, the Health-Sickness Rating Scale, or DSM-IV’s global assessment of functioning (axis V), few efforts have been made to systematically assess and quantify social functioning and impairment in patients with personality disorders (other than borderline personality disorder) or to compare one personality disorder to another. The purpose of the present study was to examine levels of functioning in a broad array of psychosocial domains in patients with DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder by means of standardized instruments, both interviewer-administered and self-report. Levels of typical functioning in the month before intake were assessed, and the four personality disorders were compared with each other and with a group of patients with current major depressive disorder and no personality disorder. We hypothesized that personality disorders would differ from each other in the degree of associated functional impairment and that patients with severe (i.e., schizotypal or borderline) personality disorders would have more functional impairment than patients with less severe (i.e., avoidant or obsessive-compulsive) personality disorders or with major depressive disorder.

Method

Subjects

Participants 18 to 45 years of age were recruited primarily from clinical services affiliated with each of the four recruitment sites of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. In all, 668 patients with at least one of four personality disorders or with major depression and no personality disorder were included. All were previously or currently in treatment: 42.7% (N=285) were outpatients in mental health settings, 12.0% (N=80) were psychiatric inpatients, 5.4% (N=36) were from other mental health or medical settings, and 40.0% (N=267) were self-referred.

Participants were prescreened to determine age eligibility and treatment status or history and to exclude patients with active psychosis, acute substance intoxication or withdrawal or other confusional states, or a history of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. All participants signed written informed consent after the research procedures had been fully explained.

The 668 patients were assigned to one of five diagnostic groups: schizotypal personality disorder (N=86, 12.9% of the total), borderline personality disorder (N=175, 26.2%), avoidant personality disorder (N=157, 23.5%), obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (N=153, 22.9%), and major depressive disorder (N=97, 14.5%). The majority of the patient group were women (63.6%, N=425), white (75.4%, N=504), and from Hollingshead and Redlich social classes I or II (38.0%, N=229 of 603). They were roughly equally distributed across the age range included in the study (mean age=32.7 years, SD=8.1).

Assessment

All patients were interviewed by experienced master’s- or doctoral-level raters with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition

(34) and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders

(35). Raters were trained by using live or videotaped interviews under the supervision of the senior author of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (M.C.Z.) at McLean Hospital. The four personality disorder diagnoses had good interrater and test-retest reliabilities (schizotypal: kappa=1.0 and 0.64, respectively; borderline: kappa=0.68 and 0.69; avoidant: kappa=0.68 and 0.73; obsessive-compulsive: kappa=0.71 and 0.74)

(36). For the assignment of patients to the study groups, diagnoses obtained from the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders received convergent support from the results of either of two contrasting approaches to axis II diagnosis: the self-report Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality

(37) or an independent clinician’s rating on the Personality Assessment Form

(6).

To assess psychosocial functioning, interviewers administered the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation—Baseline Version

(38). The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation includes questions to assess functioning in employment; household duties; student work; interpersonal relationships with parents, siblings, spouse/mate, children, other relatives, and friends; recreation; and three ratings of global functioning: global satisfaction, global social adjustment, and the DSM-IV axis V global assessment of functioning. Most areas of functioning were rated on 5-point scales of severity (1=no impairment, high level of functioning or very good functioning; 2=no impairment, satisfactory level of functioning or good functioning; 3=mild impairment or fair functioning; 4=moderate impairment or poor functioning; and 5=severe impairment or very poor functioning). Global assessment of functioning is rated on a 100-point scale, with 100 indicating the highest possible level of functioning. Ratings were made for each patient’s typical functioning in the month before evaluation. In addition, subjects completed the self-report Social Adjustment Scale

(39). Reliability of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation social functioning scales

(38,

40) and the Social Adjustment Scale

(41) has been previously established.

More detailed descriptions of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study rationale, recruitment, subject demographics, diagnostic assessments, reliability, and assessment of axis I comorbidity are available elsewhere

(36,

42,

43).

Analyses

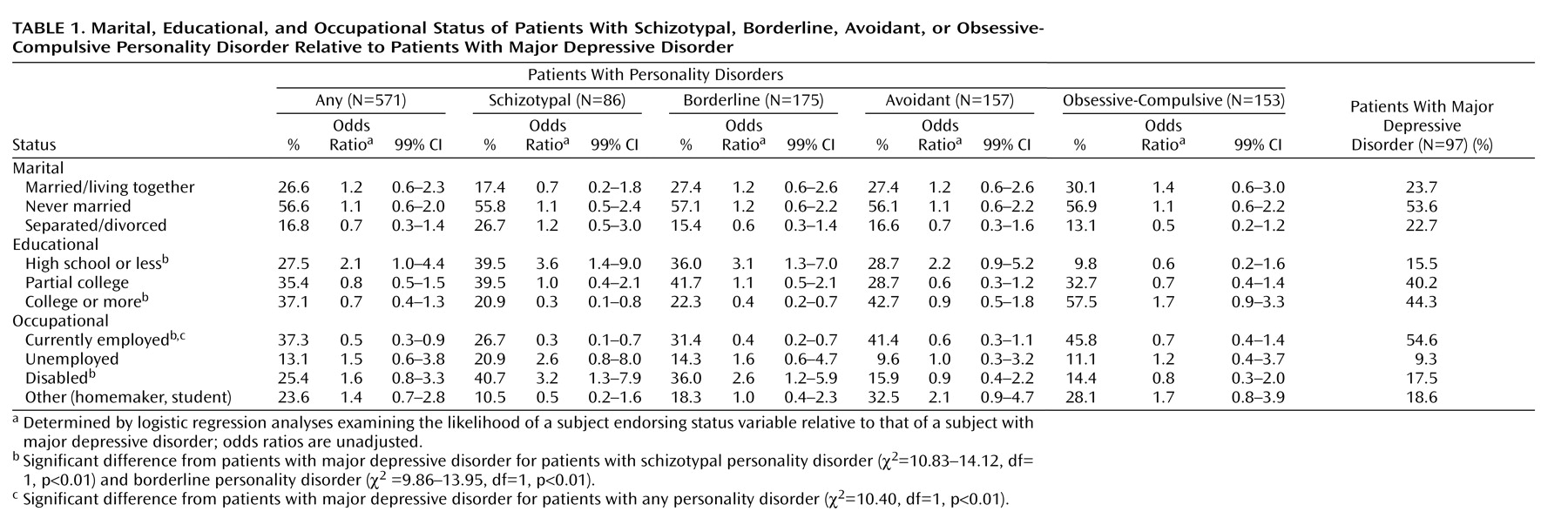

The likelihood of patients showing achievement or impairment in marital status, educational attainment, and occupational status was compared between each of the personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group by using logistic regression. Odds ratios with 99% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated that compared the major depressive disorder group with each individual personality disorder group as well as with the personality disorder group as a whole.

Means and standard deviations on each of the social functioning scales of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation were calculated for the month before intake. The general linear models procedure (analysis of covariance) was used to compare mean functioning by study group assignment. In order to determine whether significant differences in functional impairment persisted after accounting for demographic differences and comorbidity, we controlled for gender, age, minority status, and comorbid axis I psychopathology. Duncan post hoc tests were done to determine specific differences between personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group. Corresponding analyses were conducted on the Social Adjustment Scale scores.

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the likelihood that the personality disorder groups had severe impairment in any domain of functioning in the month before baseline compared with the major depressive disorder group. A separate model was done for each of the measures from the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation. The analyses controlled for the effects of gender, age, minority status, and axis I psychopathology. Goodness-of-fit for each model was assessed by using Hosmer and Lemeshow’s C statistic

(44). Odds ratios and 99% confidence intervals from the models are presented.

All statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS Version 6.12

(45). Statistical significance was set at p<0.01.

Results

Functional Status

Table 1 shows that there were no differences among the personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group on the proportion of subjects married or living with someone, separated or divorced, or never married. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder had over three times the odds of having only a high school education relative to the major depressive disorder patients and less than half the odds of having graduated college. In addition, patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder were less frequently currently employed and had two to over three times the odds of being disabled (

Table 1).

Interviewer-Rated Impairment

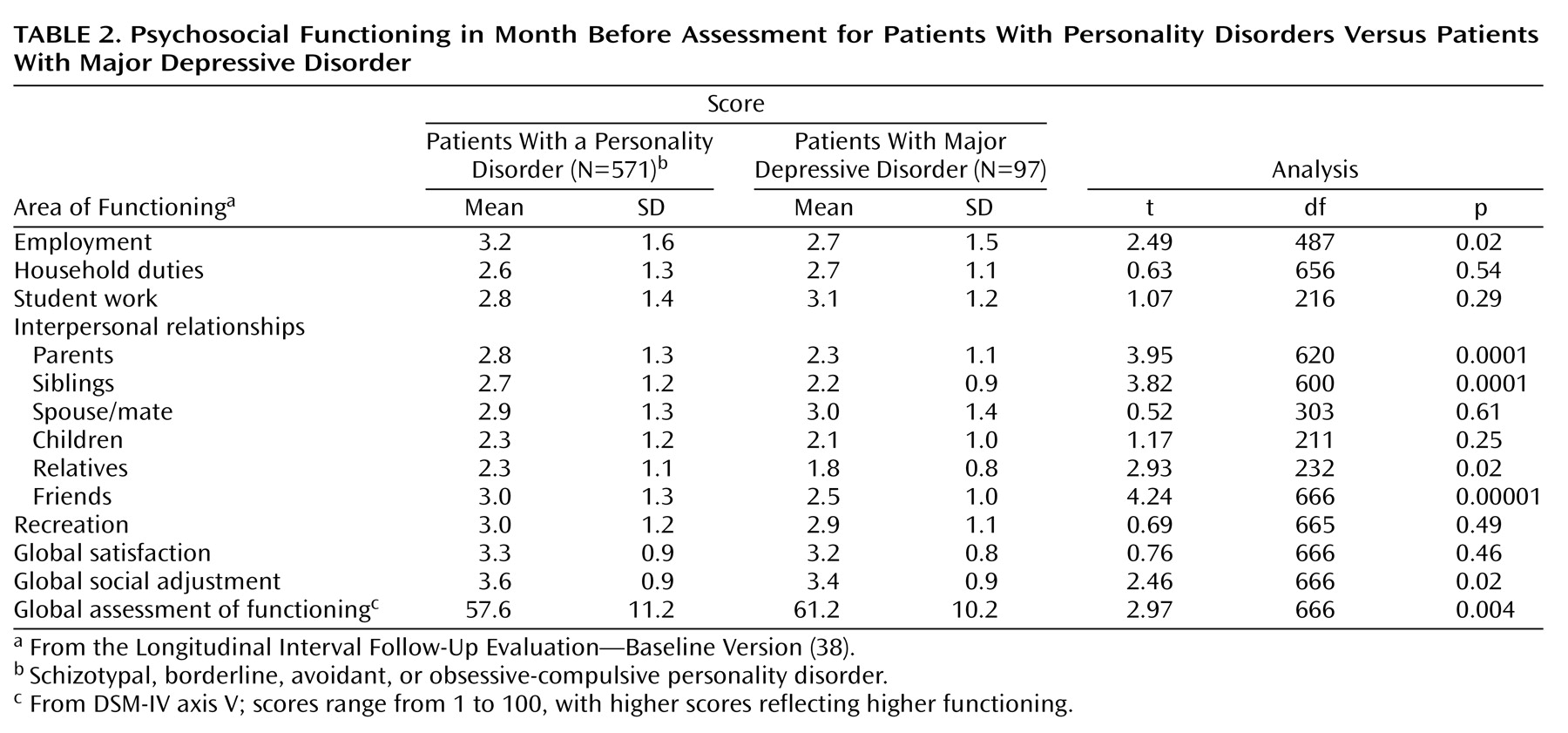

The mean level of impairment across the areas of psychosocial functioning measured during the month before assessment for patients with personality disorders ranged from 2.3 to 3.6, while the corresponding ratings for patients with major depressive disorder ranged from 1.8 to 3.4 (

Table 2). The average rating of 2.9 indicates a general mild-to-moderate level of impairment or fair to poor functioning in patients with personality disorders. Relative to that of patients with major depressive disorder, significantly greater impairment in functioning was found in patients with personality disorders for social relations with parents, siblings, and friends and for global assessment of functioning.

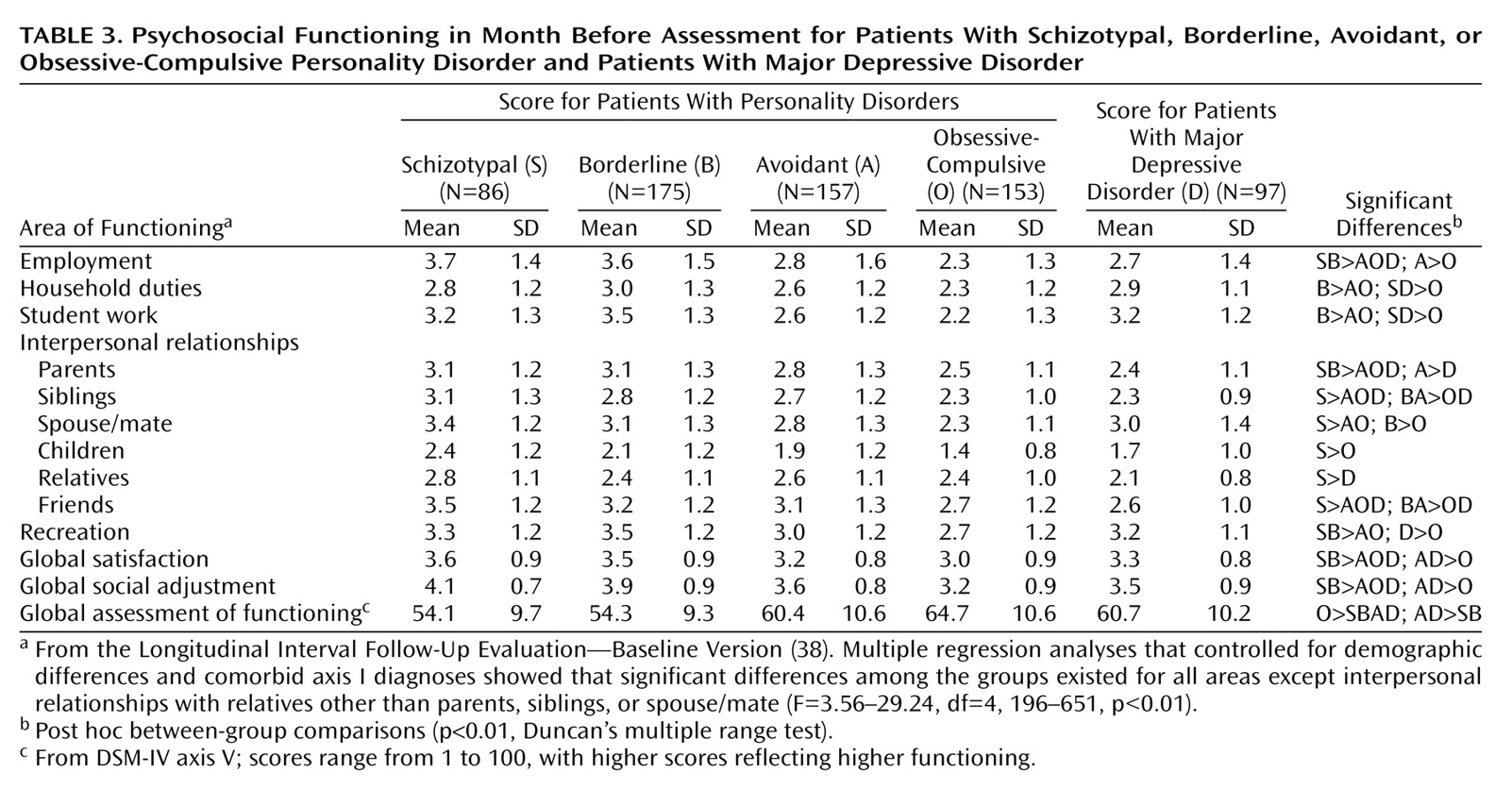

Table 3 shows the mean levels of impairment in psychosocial functioning during the month before baseline assessment at intake for the four personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder consistently were rated as exhibiting greater functional impairment than were patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder or major depressive disorder. Patients with avoidant personality disorder were intermediate. Multiple regression analyses controlling for demographic differences and comorbid axis I disorders showed that significant differences between the groups existed in all areas of psychosocial functioning in the previous month, except for interpersonal relationships with relatives (other than parents, siblings, or spouse/mate). High percentages of patients with schizotypal (98.8%), borderline (98.3%), avoidant (96.2%), and obsessive-compulsive (87.6%) personality disorder and major depressive disorder (92.8%) exhibited moderate (or worse) impairment or poor (or worse) functioning in at least one area or received a global assessment of functioning rating of 60 or below in the month before intake.

Self-Reported Impairment

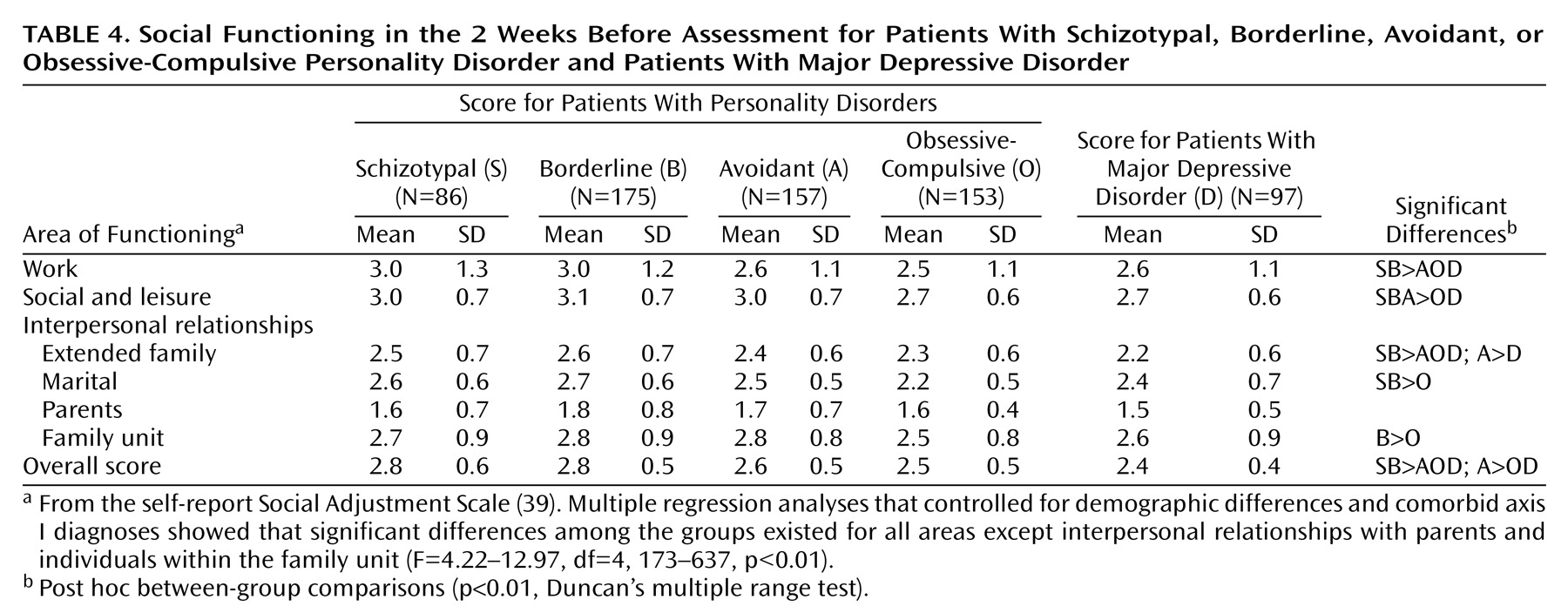

Table 4 shows self-reported impairment for the 2 weeks before assessment. Consistent with the interviewer ratings, patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder rated themselves as significantly more impaired on all individual domains of functioning and overall than those with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and major depressive disorder; patients with avoidant personality disorder remained intermediate.

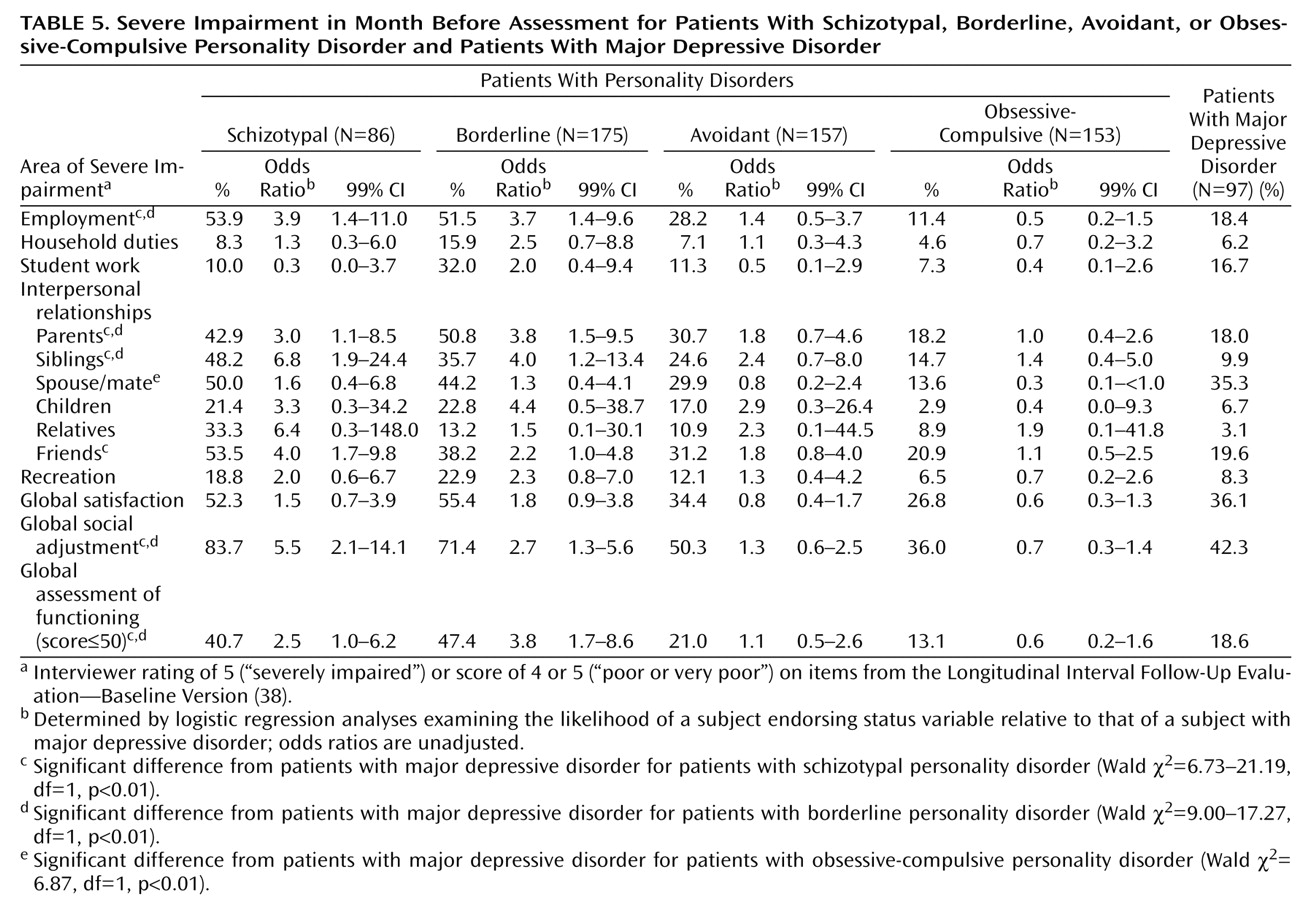

Ratings of Severe Impairment

Since average ratings of impairment in psychosocial functioning tended to be moderate among patients with personality disorders, we sought to determine how often personality disorders were associated with severe levels of impairment in contrast to major depressive disorder.

Table 5 shows odds ratios with 99% confidence intervals comparing each of the four personality disorder groups with the major depressive disorder group on the proportion of subjects rated by interviewers as severely impaired (score=5) or with poor or very poor functioning (score=4 or 5) on the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation scales during the previous month. On approximately half of the measures, the odds of patients with schizotypal personality disorder or borderline personality disorder having severe impairment were significantly greater than were those of patients with major depressive disorder. Patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were rated as severely impaired less frequently than those with major depressive disorder in many areas (odds ratios less than 1.0), although these differences were significant only for social relationships with spouse/mate, for which patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder had one-third the odds of having severe impairment.

Discussion

This study is among the first to document and quantify the extent of functional impairment found in patients with different types of personality disorders in contrast to patients having an impairing axis I disorder. Our results indicate that functional impairment due to personality disorders can be reflected by sociodemographic statuses as well as by qualitative differences in functional performance. Our failure to find differences in marital status between patients with personality disorders and those with major depressive disorder may be due to the relatively low rate of married patients in all the study groups. Older patients, in general, were more likely to be married (analyses not shown), and our study group had an upper age range limit of 45 years.

Our results supported our hypothesis that patients with personality disorders that are traditionally believed to be more severe have greater degrees of functional impairment than do patients with less severe personality disorders or major depressive disorder. Our finding the same pattern of results through self-report and interview data suggests that the excess impairment in severe personality disorders is not accounted for by interviewer expectation or bias. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder had greater impairment on virtually every measure of impairment than did patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder or major depressive disorder, regardless of whether the assessment was interview-based or by patient self-report, even after covarying for comorbid axis I psychopathology. It is of interest that although we controlled for the effects of gender in our regression models, in checking our analyses, we found no significant gender effects, implying that men and women are equally impaired from their axis II disorders. Our findings are especially noteworthy given the growing appreciation for the degree and persistence of limitations in functioning of patients with major depressive disorder. Impairment due to major depressive disorder has been found to be comparable to that of patients with chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes and arthritis

(46,

47), and major depressive disorder is the leading cause worldwide of years lived with disability according to the Global Burden of Disease Study

(48).

Although there are no Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation data on patients with personality disorders in the existing literature with which to compare our findings, our results are consistent with those of other investigators indicating poor social

(2,

4,

5,

7,

13–

18) and work

(2,

4,

7,

14–

16,

19–

22) functioning among patients with personality disorders. The mean DSM-IV axis V global assessment of functioning rating of 54 for patients with borderline personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder is similar to that reported in outpatient populations by Frances et al.

(23), Barasch et al.

(25), and Nurnberg et al.

(27). The rating is higher than that of personality disorder patients upon admission to the hospital as reported by Tucker et al.

(49), Plakun et al.

(24), Mehlum et al.

(31), Najavits and Gunderson

(50), and Levy et al.

(33). At the time of admission, a patient’s functioning might be expected to be at a low ebb. At other times of outpatient treatment (as was the case for the majority of our patients), functioning might be expected to have improved.

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder was associated with the least overall functional impairment among the personality disorders. Some might question whether some of these individuals should have received a personality disorder diagnosis at all. However, even in this group almost 90% had moderate or worse impairment or poor or worse functioning in at least one area or received a global assessment of functioning rating of 60 or less at intake, which suggests that patients with less severe personality disorders may not have widespread functional impairment but do have at least one area of significant impairment that could warrant a personality disorder diagnosis.

It should be recognized that all information about functioning obtained in this study came from the patients themselves. Therefore, it is possible that certain types of psychopathology may have influenced reporting, e.g., patients with borderline personality disorder may tend to exaggerate their difficulties, while those with major depressive disorder may minimize them. However, the argument that a depressive state leads to an overreporting of personality psychopathology would suggest that depressed patients may also exaggerate their impairments

(51). Furthermore, assessments by semistructured interview, such as those conducted for personality disorders and psychosocial functioning in this study, are believed to reduce reporting distortions by careful clinical “cross-examination” and by eliciting examples of traits, behaviors, and functioning

(52). Finally, possible reporting biases are less obvious in the case of schizotypal personality disorder, which was associated with considerable functional impairment.

These results underscore the impression of many clinicians that personality disorders are an overlooked and underappreciated source of psychiatric morbidity. Comorbid personality disorders may, in fact, account for much of the morbidity attributed to axis I disorders in research and clinical practice. Personality disorders appear likely to be a significant public health problem, and more work is needed to document the persistence of functional impairment in patients with personality disorders and its costs to patients, their families, and society. Treatment approaches with an emphasis on psychosocial rehabilitation may be needed

(53–

55) to mitigate the pernicious effects of personality disorders on functioning.

Acknowledgments

The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study is being conducted with the participation of investigators from the following sites: Brown University Department of Psychiatry, Providence, R.I.; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital, Boston; the Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Tex.; and the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine and Yale Psychiatric Institute, New Haven, Conn.