Increasing evidence suggests that psychosocial factors such as stress and depression may have a harmful impact on the course of many diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer

(1–

8), and may heighten susceptibility to infectious diseases

(9). Recent studies also have examined the effects of depression on HIV disease progression, demonstrating an association between depression and early, as well as late, disease progression in men

(10–

12) and between depression and mortality in women

(13). Alterations in key parameters of cellular immunity have been documented in depressed individuals who are otherwise healthy

(14–

18). Some studies assessing the effects of stress and depression on immune function in HIV-infected individuals have yielded a positive relationship

(19–

22), whereas others have found no association

(23–

25). Thus, the mechanisms by which stress and depression may influence disease progression and mortality in HIV infection remain to be determined.

There have been little data regarding the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in HIV-infected women, despite the fact that HIV remains a leading cause of death for U.S. women between the ages of 25 and 44 years. HIV also is the leading cause of death among African American women in this age group

(26). Estimates of the prevalence of major depressive disorder in HIV-seropositive women vary widely in the literature, with reported prevalence rates that range from 1.9% to 35% in clinical samples

(36–

38) and from 30% to 60% in community samples

(13,

39,

40). In the five-site World Health Organization Neuropsychiatric AIDS study

(41), which included men and women, prevalence rates of major depressive disorder ranged from 3.0% to 10.9% in asymptomatic HIV-seropositive subjects and from 4.0% to 18.4% in symptomatic HIV-seropositive subjects. Although women demonstrated higher depression scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale at two of the five sites participating in this multicenter study, data on gender differences for major depressive disorder were not reported.

In the largest U.S. clinical study of non-substance-abusing HIV-seropositive women (N=54), Goggin et al.

(36) reported that only 1.9% of the women had major depressive disorder and that 3.7% had dysthymic disorder. In a case series of 38 HIV-seropositive women

(42), 14% met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder, 3% had dysthymic disorder, and 48% had substance abuse disorders. In a case series of 17 HIV-seropositive women

(37), 29% met DSM-IV criteria for current major depressive disorder, and 18% met criteria for current dysthymic disorder. Studies of HIV-seropositive women that included active intravenous substance abusers have demonstrated an association between current substance abuse, depressive symptoms

(38), and major depressive disorder

(24), but not HIV status.

The wide range of estimates of major depressive disorder among the available clinical studies of HIV-seropositive women, coupled with recent epidemiological data that depressive symptoms are associated with mortality in HIV-seropositive women, underscore the need for controlled studies to ascertain the rate of depression in HIV-seropositive women and to examine its correlates. The present study addresses these issues.

Specifically, the primary objective was to determine whether there were differences in the rate of depressive and anxiety disorders in a cohort of HIV-infected women relative to a comparison group of uninfected women. Secondary objectives were to examine correlates of depression—including HIV disease stage and protease inhibitor use—and the associations between symptoms of depression or anxiety and other potential predictor variables. Analyses are based on baseline findings collected at entry into a longitudinal cohort study. Female residents of a rural area in Northern Florida who were seropositive for HIV and who were not current substance abusers were compared with a group of HIV-seronegative women who met similar enrollment criteria; both groups were recruited between 1997 and 2000. We examined presentations of depression and anxiety by using comprehensive interview-based diagnostic instruments. Finally, to better characterize mood disturbances in HIV-seropositive women, we assessed the relationship of major depressive disorder, as well as higher depressive symptom scores, to past history of major depressive disorder, stage of HIV illness, and HIV medication use. To our knowledge, this is the largest and the first controlled systematic report in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens to reflect the distribution of psychiatric disorders in HIV-infected women who are not current substance abusers.

Results

Subjects

Following telephone prescreening, 95% of eligible subjects agreed to participate and completed their baseline visit. The demographic characteristics of the 93 HIV-seropositive and 62 HIV-seronegative women were similar in most respects. Age, race, marital status, number of children and monthly income were similar between the two groups. Both groups of women were relatively young (HIV-seropositive: mean age=37.0 years, SD=9.0; HIV-seronegative: mean age=33.4 years, SD=11.1). Racial distribution was similar, with Caucasian women comprising 39.8% (N=37) of the HIV-seropositive group and 40.3% (N=25) of the HIV-seronegative group. The distribution of ethnic minorities was similar in both groups. Among HIV-seropositive women, 55.9% (N=52) were African American, and 4.3% (N=4) were Hispanic; among HIV-seronegative women, 53.2% (N=33) were African American, 4.8% (N=3) were Hispanic, and one subject (1.6%) was of “other” ethnicity. There were no significant differences in gross monthly income between the two groups of women. The HIV-seropositive women had completed an average of 11.8 years of education (SD=2.1), and the HIV-seronegative women had completed a mean of 12.5 years of education (SD=2.1).

Disease Status in HIV-Seropositive Women

Almost half of the HIV-seropositive women (45.2%, N=42) had stage A HIV infection. Thirty-three women (35.5%) had stage B infection, and a small proportion (N=17, 18.3%) had stage C infection. Thirty-one (33.3%) women were on a regimen of antiretroviral therapy that included taking protease inhibitors, 40 women (43.0%) had medication regimens that did not include protease inhibitors, and 22 women (23.7%) were not taking any medication for HIV infection.

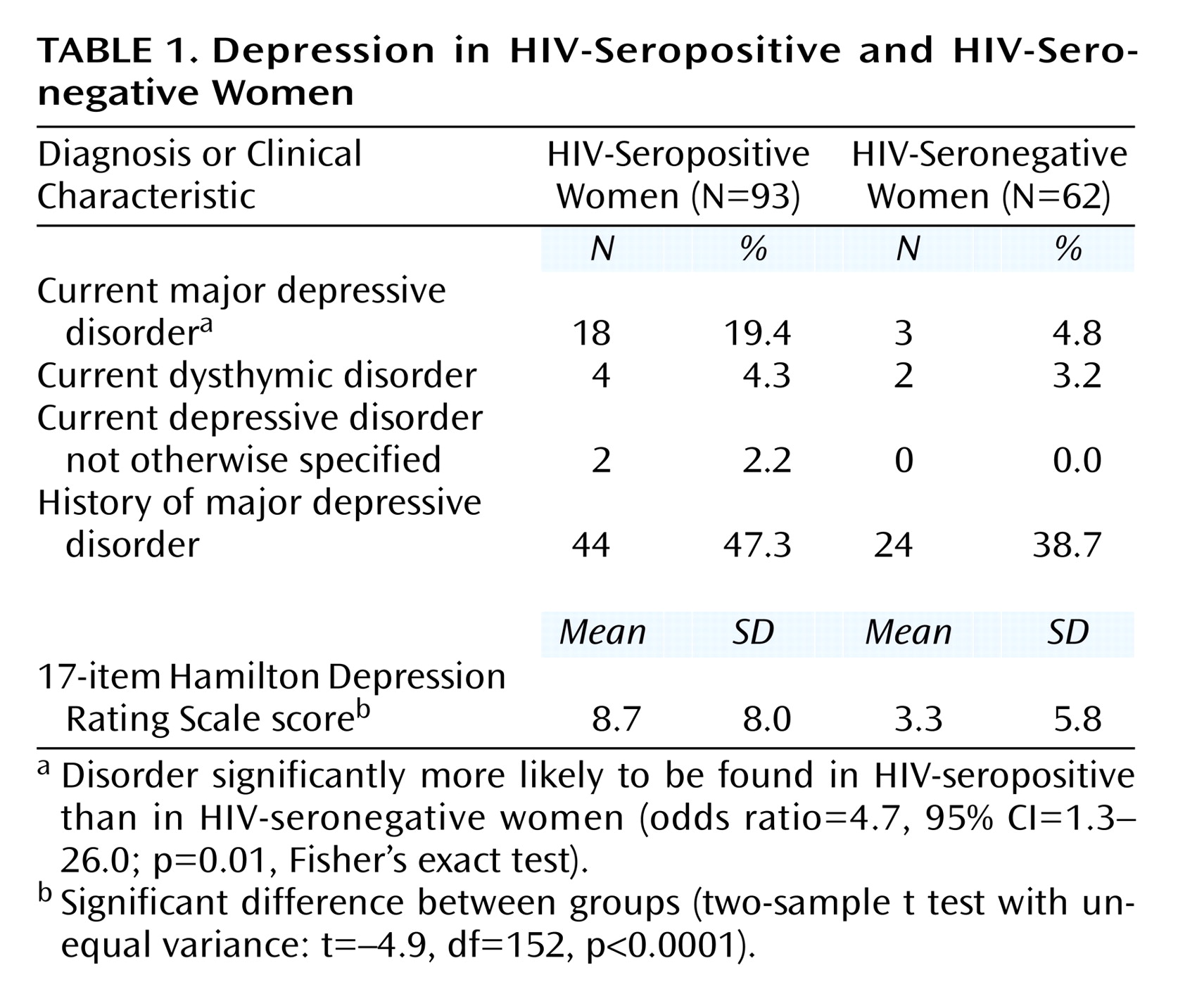

As shown in

Table 1, the proportion of women with a diagnosis of current major depressive disorder was four times greater in the HIV-seropositive group than in the HIV-seronegative comparison group, a significantly higher proportion. In contrast, the proportion of women with a history of major depressive disorder was similarly high in the HIV-seropositive group (47.3%) and the HIV-seronegative group (38.7%) (odds ratio=1.4, 95% CI=0.7–2.9; p=0.40, Fisher’s exact test).

Scores on the 17-item and 11-item Hamilton depression scales showed the greater risk and severity of depression among HIV-seropositive women as well. HIV-seropositive women with major depressive disorder had a mean 17-item Hamilton depression scale score of 16.9 (SD=7.3, median=16.0) and a mean 11-item score of 11.3 (SD=5.9, median=11.5), whereas the respective scores for HIV-infected women with no major depressive disorder were 6.5 (SD=5.2, median=6.0) and 4.0 (SD=3.5, median=4.0). Within the HIV-seronegative group, women with major depressive disorder had a mean 17-item Hamilton depression scale score of 17.8 (SD=9.2, median=15.5) and a mean 11-item score of 12.3 (SD=6. 9, median=12.5), whereas the respective scores for HIV-seronegative women with no major depressive disorder were 3.3 (SD=4.5, median=1.5) and 2.2 (SD=3.3, median=1.0).

Factors Associated With Depressive Presentations

Controlling for each baseline covariate separately did not change the association between HIV status and current major depressive disorder. Older age demonstrated a marginal association with current major depressive disorder (odds ratio=1.04, 95% CI=0.997–1.10; p=0.06, Fisher’s exact test). Bivariate models were used to examine the relationship of current major depressive disorder with other variables, holding HIV status constant as the second covariate in the model. Age, race, level of education, income, marital status, and history of major depressive disorder were not significantly associated with current major depressive disorder in any of these analyses.

The proportion of women with dysthymic disorder and depressive disorder not otherwise specified was similar in both HIV-seropositive and seronegative women. As seen in

Table 1, mean 17-item Hamilton depression scale scores were higher in the HIV-seropositive group than in the HIV-seronegative group, indicating that the HIV-seropositive women reported significantly more depressive symptoms (beta=5.4, 95% CI=3.1–7.8, where beta is the difference between group means). The 11-item Hamilton depression scale results were similar: HIV-seropositive women had a mean score of 5.8 (SD=5.7) whereas HIV-seronegative women had a mean score of 2.3 (SD=4.3) (t=4.0, df=153, p<0.0001; beta=3.5, 95% CI=1.8–5.1). The Hamilton depression scale results indicate a strong association between HIV status and depressive symptoms in both the univariate analysis above and after adjustment for a history of major depressive disorder (t=4.5, df=152, p<0.0001; beta=5.1, 95% CI=2.8–7.4).

In a series of univariate analyses, higher depressive symptom scores, as per the 17-item Hamilton depression scale, were significantly associated with older age (t=2.3, df=153, p=0.02; beta=0.1, 95% CI=0.02–0.3), Caucasian race (t=2.1, df=153, p=0.04; beta=2.6, 95% CI=0.1–5.0), and less education (t=2.1, df=152, p=0.04; beta=–0.6, 95% CI=–1.2 to –0.02). Marital status and income were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms. After adjustment for age, race, and years of education, HIV status remained significantly associated with depressive symptoms as measured by the 17-item Hamilton depression scale (t=4.1, df=149, p<0.0001; beta=4.8, 95% CI=2.5–7.2).

Anxiety

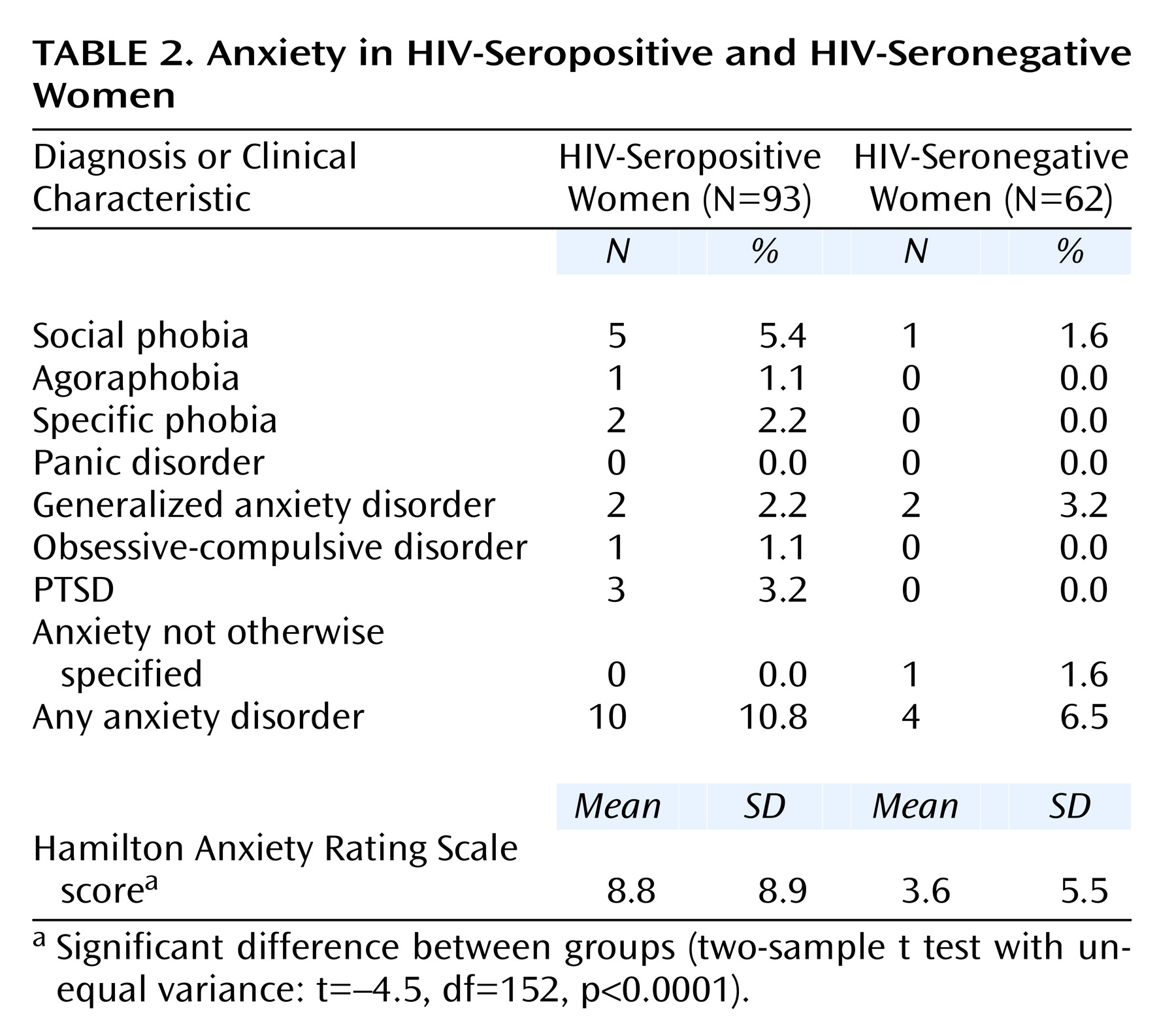

As seen in

Table 2, there was no significant difference between the HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women in the proportion having any of the anxiety disorders. Social phobia was found in 5.4% (N=5) of HIV-seropositive women and in 1.6% (N=1) of HIV-seronegative women, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. When any anxiety disorder was considered, 10.8% (N=10) of the HIV-seropositive women and 6.5% (N=4) of the HIV-seronegative women had at least one anxiety disorder diagnosis, a difference that was not statistically significant (odds ratio=1.7, 95% CI=0.5–7.8; p=0.54, Fisher’s exact test). Nevertheless, HIV-seropositive women had higher scores on the 14-item Hamilton anxiety scale than did the HIV-seronegative women (beta=5.2, 95% CI=2.7–7.7). Thus, relative to HIV-seronegative women, HIV-seropositive women had higher levels of anxiety symptoms but similar rates of anxiety disorders.

Substance Abuse and Dependence

A large proportion of women in both groups reported a history of substance abuse or dependence. The proportion of women with a history of substance abuse or dependence was higher in the HIV-seropositive group (50.5%, N=47) than in the HIV-seronegative women (30.6%, N=19), a difference that was statistically significant (odds ratio=2.3, 95% CI=1.2–4.6; p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test). Adjusting for history of substance abuse or dependence did not substantively alter the relationship of positive HIV serostatus and current major depressive disorder from the aforementioned unadjusted odds ratio of 4.7 (odds ratio=4.0, 95% CI=1.1–14.5; χ2=4.4, df=1, p=0.04).

Antiretroviral Medication and Depression

To understand further the association of antiretroviral medication use and depression, we investigated the relationships between use of specific classes of antiretroviral medication and current major depressive disorder. Among the HIV-seropositive women who were receiving protease inhibitor therapy (N=31), nine women (29.0%) had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Among the 62 women who were receiving antiretroviral treatment that did not include a protease inhibitor or who were not taking any antiretroviral therapy medication, the proportion of women with major depressive disorder (14.5%, N=9) was lower, but this difference was not statistically significant (odds ratio=2.4, 95% CI=0.7–7.8; p=0.10, Fisher’s exact test). Mean 17-item Hamilton depression scale scores were higher in the 31 women receiving protease inhibitor therapy (mean=10.6, SD=9.1) than in the 62 women who were taking other antiretroviral medications or no medications (mean=7.8, SD=7.3), but this difference also was not statistically significant (t=1.6, df=91, p=0.10; beta=2.8, 95% CI=–0.6 to 6.2). In a univariate analysis of those taking antiretroviral therapy, protease inhibitor use was associated with current major depressive disorder (odds ratio=8.6, 95% CI=1.0–394.1; p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test); however, this association did not remain significant after adjustment for stage of HIV illness (odds ratio=5.7, 95% CI=0.6–290.1; χ2=1.6, df=1, p=0.20). The proportion of HIV-seropositive women taking antiretroviral therapy with major depressive disorder did not significantly differ by CDC stage (stage A: 18% [N=6 of 33], stage B: 33% [N=11 of 33], stage C: 25% [N=1 of 4]). Furthermore, for the entire group of HIV-seropositive women, the proportion of women with major depressive disorder did not significantly differ by CDC stage (stage A: 15% [N=7 of 48], stage B: 28% [N=11 of 39], stage C: 20% [N=1 of 5]). The mean 17-item Hamilton depression scale scores for those women in stages A, B, and C were 7.5, 10.0, and 9.8, respectively (F=1.16, df=2, 89, p=0.30); the corresponding 11-item Hamilton depression scale scores were 5.1, 6.5, and 6.6 (F=0.7, df=2, 89, p=0.50).

Protease Inhibitors and Anxiety

Use of protease inhibitors was not associated with anxiety disorders or symptoms. In a univariate analysis, Hamilton anxiety scale scores were associated with protease inhibitor use (t=2.07, df=152, p=0.02; beta=5.47, 95% CI=0.03–10.42) but not after adjustment for HIV disease stage (t=0.41, df=151, p=0.34; beta=1.6, 95% CI=–1.8 to 5.0).

Discussion

We found a high rate of current major depressive disorder (19.4%) among the HIV-seropositive women at entry into our cohort study. Interpreting these findings in the context of reported work in this field is complicated by the small number of published studies of mood disorders in women and the diverse demographic characteristics, assessment methods, and small sample sizes across the reported clinical studies. The low prevalence rates for depressive disorder diagnoses (1.9%) reported by Goggin et al.

(36) are similar to Brown et al.’s finding of a 5% rate of major depressive disorder in a sample of 43 non-substance-using women in the military

(50). Investigators studying substance-abusing populations have reported rates ranging from 20% to 35%

(38,

42). However, these studies were limited by the lack of a comparison group of HIV-seronegative women. Goggin et al.

(36) attributed their low depressive disorder rates to the absence of current substance use/dependence. However, our subjects also had no current substance use/dependence, yet they had a much higher rate of major depressive disorder relative to population norms for women in this age range. The proportion of HIV-seronegative women in our cohort who had current major depressive disorder was 4.8%, which is similar to the 1-year prevalence rate in women seen in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (4.0%)

(51) and slightly less than the 30-day prevalence rate seen in the National Comorbidity Survey (6.4%)

(52).

The high rate of past major depressive disorder found in our cohort (47.3% in HIV-seropositive and 38.7% in HIV-seronegative subjects) is consistent with the 22.1%–61.0% lifetime prevalence of mood disorders seen in other studies of HIV-seropositive and at-risk HIV populations

(32,

41,

53–56) and much higher than the lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder reported for women in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (7.0%)

(51) and the National Comorbidity Survey (21.3%)

(52). Thus, consistent with other studies of HIV-seropositive women and women at risk for HIV, our cohort had a much higher lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder.

Ickovics and colleagues

(13) recently reported adverse health effects associated with depressive symptoms in longitudinal analyses from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study, a large epidemiologic cohort study of HIV-infected women. Using a screening tool for assessment of depressive symptoms (the CES-D Scale), the HIV Epidemiology Research Study investigators found that after clinical, substance abuse, and sociodemographic characteristics were controlled, HIV-infected women with chronic or intermittent depressive symptoms over a 7-year period were at greater risk of HIV disease progression (decline in CD4 cell count and death) than were women with limited or no depressive symptoms. Unlike our study, the HIV Epidemiology Research Study had no control group. Forty-six percent of women in the HIV Epidemiology Research Study cohort reported substance abuse during the study, a factor that may have contributed to the high proportion of women classified as having chronic (42%) or intermittent (35%) depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the actual prevalence of major depressive disorder could not be assessed, given that self-report measures of depressive symptoms are standard in community-based, epidemiologic investigations. Thus, controlled clinical studies, like the present study, are needed to determine a more reliable estimate of the frequency of major depressive disorder among HIV-infected women.

We found a higher rate of anxiety symptoms in HIV-seropositive women. Despite this observation, the proportion of women with anxiety disorders was not significantly different between the HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative groups. There are few studies regarding the prevalence of anxiety disorders in HIV-seropositive populations, particularly in women. Goggin et al.

(36) found a rate of 1.9% for generalized anxiety disorder in HIV-seropositive women. Among HIV-seropositive men in the United States, there was no difference in the prevalence rate of current anxiety disorders between HIV-seropositive men and a comparison group of uninfected men (4% had social phobia, 3% had specific phobias, 2% had obsessive-compulsive disorder, 2% generalized anxiety disorder, and 12% any anxiety disorder)

(57). In a case series from a clinic population in France, 7.7% of patients had diagnoses of anxiety disorders according to DSM-IV criteria

(58). Thus, although anxiety symptoms were seen more often in the HIV-seropositive women, anxiety disorder diagnoses were not. The 10.8% of HIV-seropositive women with any anxiety disorder observed in our study group is consistent with that observed in other cohorts of HIV-seropositiveindividuals.

We explored the possibility that the higher rate of major depressive disorder in our cohort of HIV-seropositive women was related to the use of protease inhibitors. Although we found that 29% of HIV-seropositive women taking protease inhibitors had major depressive disorder compared with 14.5% in women taking no antiretroviral therapy or a medication regimen that did not include protease inhibitors, we did not find a statistically significant association of protease inhibitor use and major depressive disorder. One possible explanation for this may be that the small number of cases of major depressive disorder in the cohort of HIV-seropositive women did not provide adequate power to detect significant differences. However, two recent studies focusing on men found positive effects on mood in individuals treated with protease inhibitors and no increase in depression

(59,

60). The present study may suggest the need for further investigation of the possible association of protease inhibitor use and depression in women.

Several potential methodological limitations of the study are recognized. It is possible that features of the recruitment process introduced a bias (toward more or less psychopathology) into one or both samples. For example, identifying comparison subjects through friendships with participants may bias toward better mental health, since individuals with someone to refer may have a larger or more active network of social support from which to recruit.

Psychiatric diagnoses were confirmed at consensus conferences by using an inclusive diagnostic approach, and interviewers as well as consensus reviewers were not blinded regarding subject serostatus. In our experience, we have not found a satisfactory way to maintain such a blind and achieve validation of the consensus diagnosis. Thus, the potential for a bias in psychiatric diagnoses is small but possible.

Another potential methodological difficulty in studies of depression in populations with known medical illness is to distinguish symptoms of depression from symptoms of medical illness

(61). In this and previous studies of HIV populations, to address this possible confounding, we have analyzed symptom scores from both the 17-item Hamilton scale and a modified 11-item Hamilton scale that deletes six items of physical symptoms potentially related to HIV disease

(20). In the present study, HIV-seropositive women still had higher scores on the 11-item Hamilton depression scale than did the HIV-seronegative women, suggesting that depression was not confounded by HIV disease symptoms.

Finally, it should be recognized that the participants were women who were residing in rural Florida, a nonepicenter location, and represented two predominant racial groups, African American and Caucasian. Thus, this study cannot necessarily be generalized to Hispanic, Asian, or urban populations, nor to active substance abusers.

Several strengths of the present study should be noted. Study participants underwent comprehensive interview-based assessments for mood and anxiety; structured, standardized psychiatric instruments and consensus diagnoses were used. Because one of the general aims of the longitudinal cohort study was the determination of depression’s effects on immune function, we excluded subjects with current alcohol or substance abuse/dependence and included a comparison group of HIV-seronegative women. Thus, the rate of depression found in this cohort was not confounded by active substance abuse.

Women represent an increasing percentage of the HIV epidemic in the United States, and there is a paucity of information on psychiatric diagnoses in this population. The baseline findings from this ongoing longitudinal cohort study suggest that HIV-seropositive women are at significantly greater risk of major depressive disorder compared with a demographically similar group of HIV-seronegative women. To our knowledge, this is the largest clinical study and the first controlled investigation of depression and anxiety in HIV-infected women who are not active substance abusers. Our finding of higher rates of current major depressive disorder in HIV-seropositive women who are not current substance abusers requires confirmation from other studies of HIV-infected women receiving current regimens of antiretroviral therapy. It is noteworthy that the rate of major depressive disorder in the present study of HIV-seropositive women is consistent with reported rates of major depressive disorder in women with cancer

(62) as well as in women with cardiovascular disease

(6). Furthermore, the finding that nearly 20% of HIV-seropositive women have diagnosable major depressive disorder is consistent with recent epidemiologic data documenting that 42% of HIV-seropositive women experience chronic depressive symptoms

(13). Our findings suggest that HIV-infected women should be screened and assessed for depression. Further research is required to determine if effective antidepressant treatment is associated with improved survival in HIV disease progression, in addition to relief of depression and improved quality of life.