Deficits in emotional perception and processing have been well described in patients with schizophrenia

(1–

3). Impairments in olfactory perception and processing have also been identified, with deficits in identification, detection threshold sensitivity, memory, and discrimination being reported

(4–

9). Olfaction has been associated with emotions and emotionally laden memory, with evidence of overlapping limbic system structures

(10,

11) and similar right hemisphere dominance for both olfactory and emotional stimulus processing

(12,

13). Given the configuration and relevance of the underlying neural substrate, and the evidence of performance deficits in patients with schizophrenia, psychophysical probes of the olfactory system may hold special promise for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. They may elucidate limbic system dysfunction, which is thought to be responsible for the well-known deficits in emotional reactivity, responsiveness, and anhedonia observed in schizophrenia. Despite this relationship between olfactory and emotion brain systems, there has been little direct investigation of this aspect of olfactory function in patients with schizophrenia.

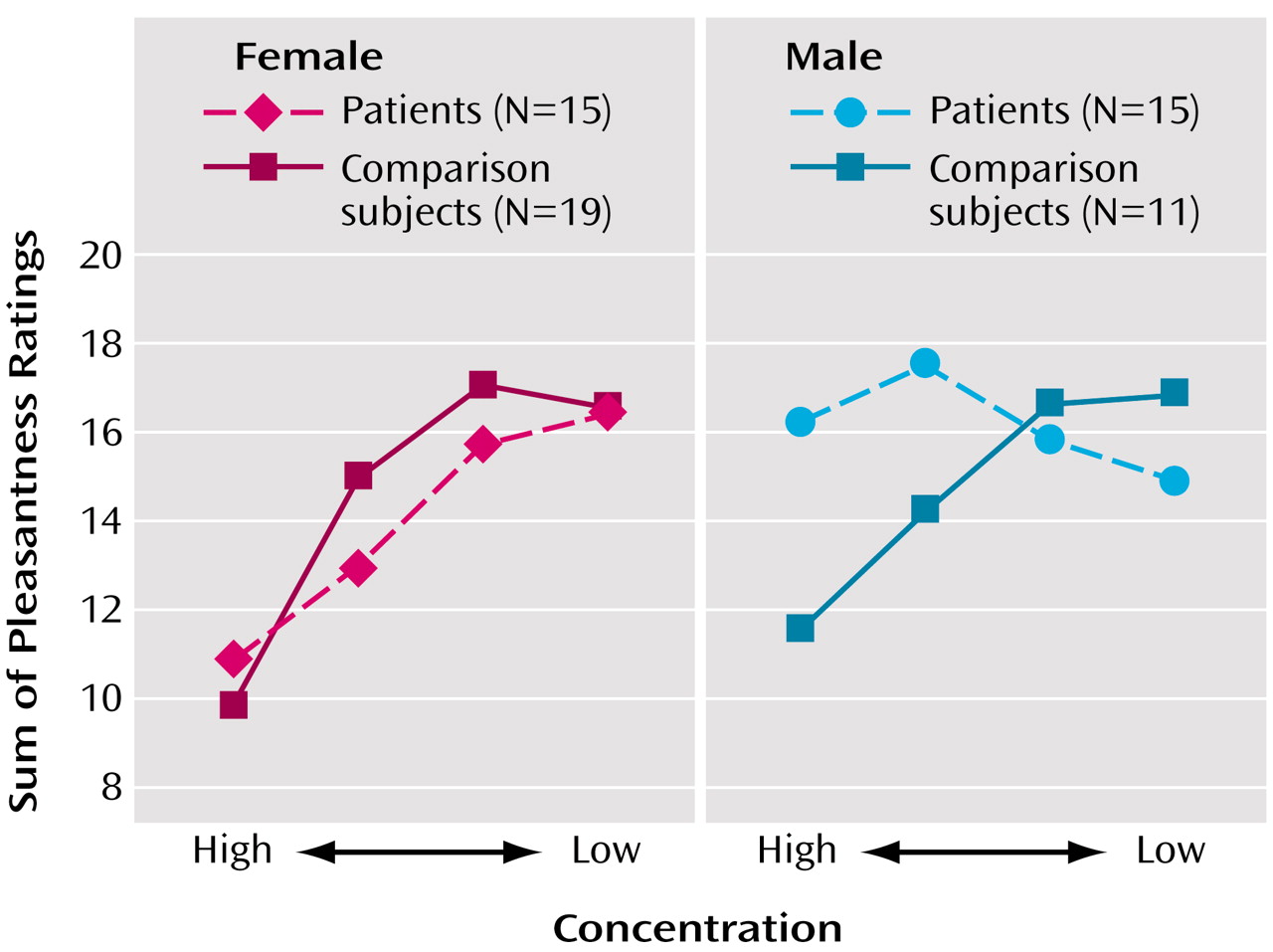

Recently, Crespo-Facorro and colleagues

(14) found that schizophrenia patients subjectively experienced an unpleasant odor in a manner similar to healthy volunteers but demonstrated impairment in the experience of a pleasant odor. Analysis of odor-evoked regional cerebral blood flow data revealed a failure to activate limbic/paralimbic regions during the experience of unpleasant odors, recruiting a compensatory set of frontal cortical regions instead. In another study by Hudry et al.

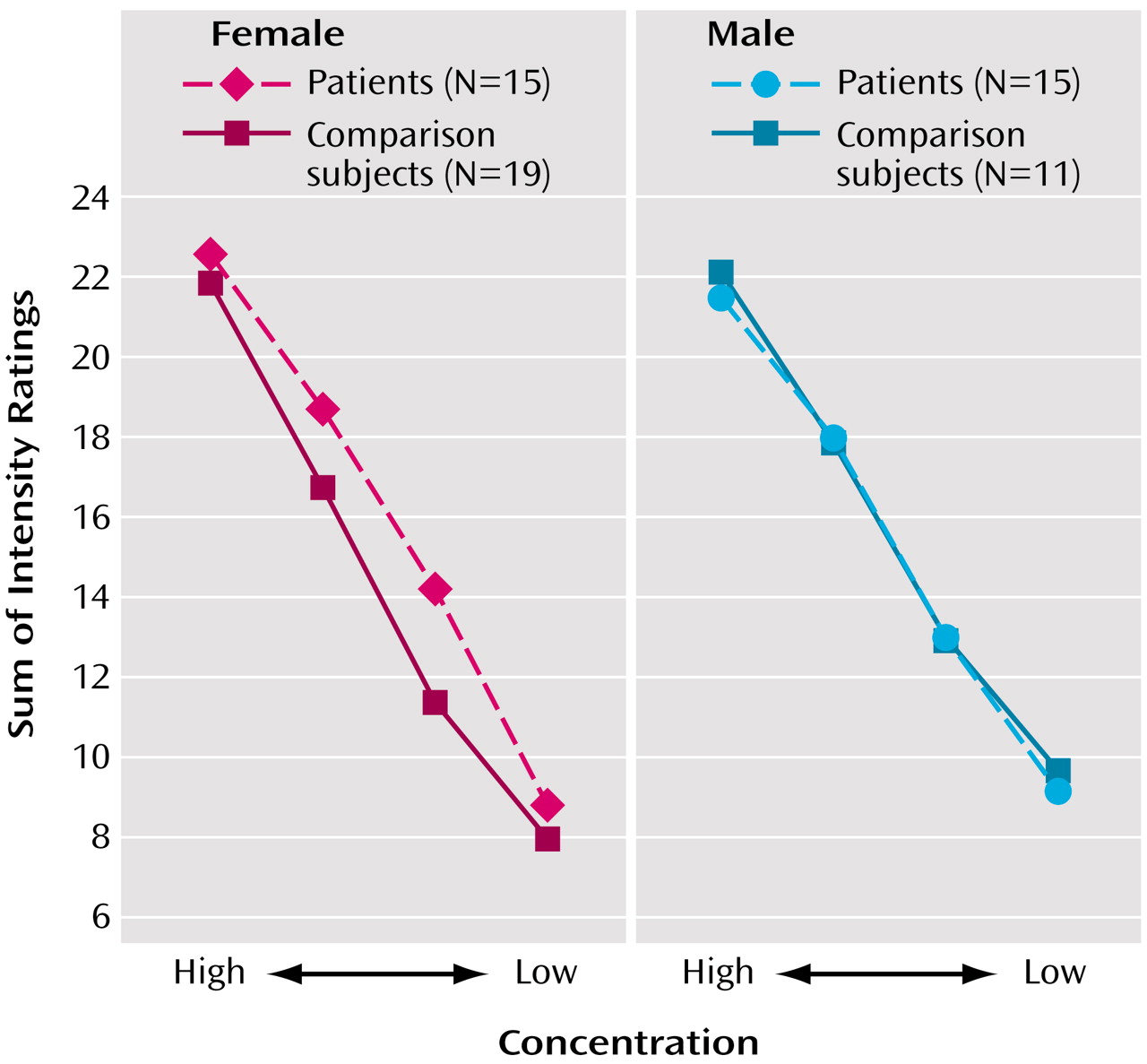

(15), patient ratings of odor intensity, pleasantness, familiarity, and edibility across 12 different odors showed deficits in ratings for pleasantness, familiarity, edibility, and identification against the background of intact intensity ratings. Both studies, however, used disparate odors to probe the hedonic aspects of odor processing, which may have introduced confounding effects of different chemical makeup and trigeminal contributions among the target odorants.

A number of psychological attributes can be assigned to odors, including strength, pleasantness, and quality

(16). Studies in healthy people that have used intensity and pleasantness ratings of some olfactory stimuli (e.g., amyl acetate, furfural), showed that pleasantness ratings are highest (i.e., most pleasant) at weak concentrations and decline progressively (i.e., become more unpleasant) as odorant concentration increases

(17,

18). Tests based upon such scales allow for probing bipolar dimensions of pleasantness using a single odor, avoiding potential confounds posed by using disparate pleasant and unpleasant odors that might bring other confounding aspects into the evaluation process (e.g., basal intensity, familiarity, or chemical composition differences).

Discussion

These data provide evidence for an abnormality in the ability to process the hedonic properties of odors in patients with schizophrenia. Specifically, men with schizophrenia demonstrated a significant disruption in their ability to attach the appropriate hedonic valence to a pleasant odor, despite giving intensity ratings that were in the normal range. This behavioral response is consistent with the clinical observation that patients with schizophrenia frequently experience anhedonia and that male patients tend to show a greater burden of deficit with regard to such symptoms

(33,

34). By using a single odorant that varied in pleasantness by intensity, we minimized potential confounds in these ratings due to differences in odor composition and other qualitative characteristics (e.g., familiarity).

Our findings are compatible with those of Crespo-Facorro et al.

(14), who reported significant deficits in attributing the appropriate hedonic valence to pleasant stimuli. While they did not specifically address sex differences, we note that their study included only two female subjects. This observation lends indirect support for the current finding that men with schizophrenia have deficits in the ability to attach appropriate hedonic valence to pleasant odors. In the only other study of olfactory hedonics in schizophrenia, Hudry et al.

(15) also found deficits in odor pleasantness, familiarity, edibility, and identification in schizophrenia. However, while male patients were more impaired in odor familiarity judgments, they did not differ from female patients in pleasantness scores, in contrast to our study. A possible reason for the differences in our findings with those of Hudry et al. is the method used to assess pleasantness. In the Hudry et al. study, pleasantness scores were an average of ratings given to a number of different odor types, perhaps introducing confounding effects of differences in familiarity, pleasantness, and chemical composition of the target odors. Taken all together, these studies and ours document a disruption of odor hedonics in patients with schizophrenia and that such deficits occur independent of odor intensity.

While previous studies of odor identification, detection threshold sensitivity, memory, and discrimination in schizophrenia have generally not supported a diagnosis-specific sex difference in olfactory abilities (see reference

5 for a meta-analytic review), there are compelling reasons to expect such differences in patients suffering from schizophrenia. Clinically, sex differences have been reported in schizophrenia, with women having a later onset, milder course, and more affective symptoms

(35–

37). With regard to olfaction in schizophrenia, Kopala and Clark

(38) have detailed a model where such potential sex differences in olfactory abilities are modulated by estrogen in olfactory-related brain regions. Indeed, in the brains of both men and women, estrogen α and β receptors and progesterone, androgen, and prolactin receptors are widely distributed in a number of extrahypothalamic basal forebrain sites including the amygdala, lateral septum, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, nucleus of the diagonal band, basal nucleus of Meynert, periaqueductal gray matter, and islands of Calleja

(39). These brain areas are intimately involved in olfactory processing and underscore how hormonal differences or disruption may influence the interplay among olfactory, emotional, and cognitive processes

(5,

40,

41). Tasks of odor hedonics may uniquely tap the convergence of emotional and olfactory processing units. Further studies detailing the relationship of hormonal factors to olfactory functions are clearly needed.

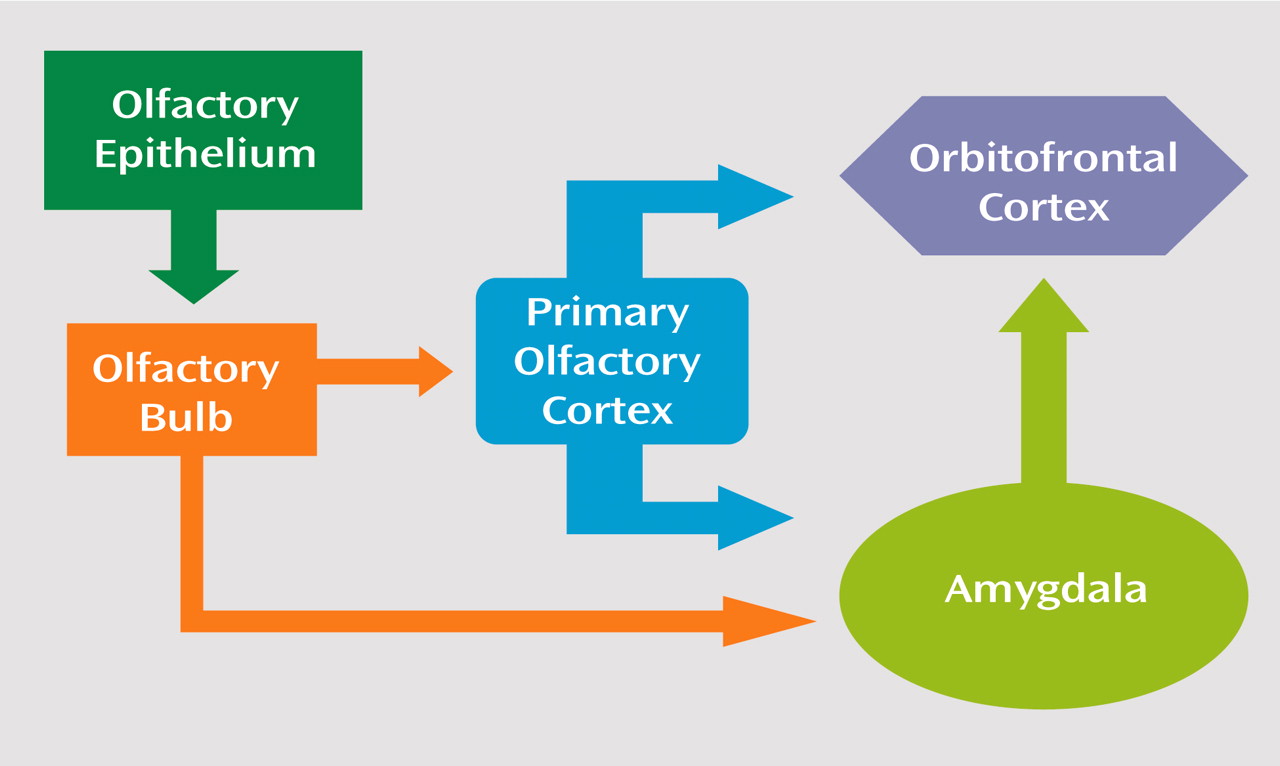

In humans, a strong and relatively consistent activation of the right orbitofrontal cortex by olfactory stimuli has been observed

(42,

43), and involvement of the amygdala has also been described in olfactory stimulation tasks

(44). There is also considerable evidence that the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex play a role in mediating emotional experience and expression

(45–

47). Within this general framework, the connectivity of the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex is consonant with a role for these regions in the processing of information concerning the emotional and motivational significance of olfactory cues

(48–

53).

In a study of temporolimbic and neocortical gray and white matter volumes in patients with schizophrenia, Gur and colleagues

(54) found significant sex differences in amygdala volumes. Specifically, while 8% of male patients showed a decrease in volume, 10.5% of female patients showed an increased volume in these structures. It may be the initial processing of the olfactory stimulus at the level of the amygdala that is disrupted in male patients, preventing or degrading further processing in orbitofrontal regions (

Figure 3). Support for this hypothesis can be seen in cerebral imaging studies in healthy subjects where increased blood flow in the amygdala in response to unpleasant odors has been demonstrated

(44). In addition, a study by Hudry and colleagues

(55) also demonstrated that pleasantness ratings on olfactory tests are significantly reduced in patients whose seizures originate in the amygdala and hippocampus.

A few limitations should be noted. First, a single odor was used for the intensity and pleasantness ratings. Whether the observed diagnosis-specific sex difference in hedonic attribution can be generalized to other odorant types remains to be examined empirically. The current design, however, used a single odor that had been shown to vary in hedonic properties with changes in intensity in healthy volunteers. The advantage of this test paradigm is that it avoids potentially confounding differences caused by using two different odorants that might have divergent chemical composition and odor qualities (e.g., vanillin versus skatole). Second, while intensity ratings did not differ between subjects, suprathreshold intensity ratings are sometimes less sensitive to alterations in odor perception

(56), suggesting that more work may be needed on this point. Third, our patient group included young adults with mild to moderate symptoms and without comorbidity. The generalizability of findings to older adults with a broader range of symptoms merits further study. Last, the precise anatomic and physiologic mechanisms underlying this deficit are not yet clear. Relating odor pleasantness and intensity ratings to MRI volumetric measures or functional imaging assessments (e.g., PET, fMRI) of amygdala and orbitofrontal regions will also help to discern whether there is a structural or physiologic component to the observed psychophysical deficit.

In summary, these data support a significant deficit in hedonic processing of odors in men with schizophrenia and suggest a significant disruption in olfactory-limbic brain regions responsible for attaching emotional valence to sensory stimuli. This impairment in hedonic ratings cannot be explained by poorer odor perception, since both patients and comparison subjects did not differ with regard to basic intensity ratings, and all odors were presented at suprathreshold levels. Future studies examining the underlying structural and physiological etiologies/mechanisms for these impairments will be important in furthering our understanding of this phenomenon.