Symptoms of depression may cause or exacerbate physical disability in older individuals

(1–

7) and may do so to a greater extent than other common chronic diseases such as hypertension, arthritis, heart disease, and diabetes

(8–

12). The World Health Organization estimated that major depressive disorder was the fourth leading cause of disability in 1990, and it is projected to become the second leading cause of disability (behind heart disease) in the coming decades

(13,

14). Depressive symptoms may also exacerbate cognitive impairment in elderly persons

(15–

17), leading to further limitations in independent functioning, and, therefore, increased need for caregiving and supervision from family members

(18,

19).

Depressive symptoms are quite common among older individuals living in the community. Among individuals age 60 years or older, the reported prevalence of major depressive disorder ranges from 1% to 5% and the reported prevalence of significant but milder depression ranges from 7% to 23%

(20–

22). Compared to younger depressed adults, older individuals may be more likely to report “anhedonia” (i.e., markedly diminished interest or pleasure in usual activities) and somatic complaints (e.g., fatigue and pain)

(23). These specific depressive symptoms may be less likely to be detected or treated by health care providers

(24–

26).

Depressive symptoms are associated with greater impairment and decreased quality of life among patients with coexisting chronic illnesses, such as emphysema

(27), cancer

(28), and diabetes

(29). When depression coexists with other medical conditions, the resulting disability appears to be additive

(10,

30).

In addition to their substantial negative effect on individuals’ independent functioning and quality of life, depressive symptoms are associated with high economic costs to both patients and insurers. Depressed individuals, including depressed elderly persons, use two to three times as many medical services as people who are not depressed

(29,

31–33). Depressed individuals are also more likely to miss time from work, further increasing the societal economic burden attributable to depressive symptoms

(8,

9,

11).

Little is known, however, about the extent to which depressive symptoms lead to increased use of unpaid care from family members and friends (informal caregiving). The economic value of such informal caregiving is substantial in other chronic medical conditions such as dementia

(19,

34) and cancer

(35), and the total economic value of informal caregiving in the United States in 1997 was estimated to be $196 billion, or more than twice the amount paid for nursing home care

(36). If informal caregiving costs for depressive symptoms are substantial, their exclusion from analyses of the total cost of depression will result in an underestimation of the true societal impact of depression and an undervaluing of the cost-effectiveness of interventions to treat depressive symptoms

(37,

38).

Given the high prevalence of depressive symptoms among older individuals, the negative effect of those symptoms on independent functioning, the existence of effective treatments for depressive symptoms

(39), and the rapidly aging U.S. population, a fuller understanding of the extent to which depressive symptoms among older persons may lead to informal caregiving is needed. We used data from a nationally representative population-based sample of older Americans to determine the association of depressive symptoms with limitations in independent functioning and to calculate the additional time and related costs associated with informal caregiving to address those limitations. To our knowledge, this is the first study of the extent and costs of informal caregiving for depressive symptoms in older Americans.

Method

Data Source

We used data from the baseline survey (1993) of the Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) cohort of the Health and Retirement Study

(40). The Health and Retirement Study is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of adults conducted by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging. AHEAD respondents included 7,443 people age 70 years or older at the time of the baseline interview (i.e., born in 1923 or before). Interviews were conducted in person or over the telephone in English or Spanish. Proxy respondents were interviewed if the selected respondent was unable to answer the survey questions independently. A response rate of 80.4% was achieved.

Identification of Depressive Symptoms

Each respondent was asked to answer “yes” or “no” to the following eight statements taken from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale)

(41): Much of the time during the past week: 1) I felt depressed, 2) I felt that everything I did was an effort, 3) my sleep was restless, 4) I was happy, 5) I felt lonely, 6) I enjoyed life, 7) I felt sad, and 8) I could not “get going.” For each respondent, the number of “yes” responses to statements 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and the number of “no” responses to statements 4 and 6 were summed to arrive at a total depressive symptom score that ranged from 0 to 8. Survey respondents were then sorted into three mutually exclusive categories on the basis of their total depressive symptom score: 1) no depressive symptoms, 2) one to three depressive symptoms, and 3) four to eight depressive symptoms. This abbreviated 8-item version of the CES-D Scale has comparable reliability and validity to the widely used and validated 20-item CES-D Scale

(41–

43). Further information regarding the comparability of the 20-item and 8-item CES-D Scales has been published previously

(44).

The AHEAD study identified proxy respondents for individuals unable or unwilling to complete the survey by themselves

(40). Approximately 10% of AHEAD respondents were represented by a proxy and so could not be asked the CES-D Scale questions. This analysis includes only self-respondents (N=6,649), since answers to the CES-D Scale items were not available for respondents represented by a proxy.

Identifying Limitations in Independent Functioning

An individual was considered to have a limitation in activities of daily living (i.e., eating, transferring, toileting, dressing, bathing, walking across a room) if he or she reported having “difficulty,” using mechanical assistance (e.g., a walker or wheelchair) or receiving help with any of the six activities of daily living. An individual was considered to have a limitation in instrumental activities of daily living (i.e., preparing meals, grocery shopping, making phone calls, taking medications, managing money) if he or she reported needing help with or not performing an instrumental activity of daily living because of a health problem

(45).

Caregiving Hours

Respondents were identified as recipients of informal care if 1) a relative or unpaid nonrelative (with no organizational affiliation) provided in-home assistance with any activity of daily living “most of the time” and/or 2) a relative or unpaid nonrelative (with no organizational affiliation) provided in-home assistance with any instrumental activity of daily living because of a health problem

(45).

The number of hours per week of informal care was calculated by using the average number of days per week and the average number of hours per day that the respondent reported receiving assistance from informal caregivers during the prior month. The method used for calculating weekly hours of care from the AHEAD data has been described previously

(46,

47).

Potential Confounding Variables

Since the goal of the analysis was to quantify the

additional hours of informal caregiving attributable to depressive symptoms, we controlled for the presence of other comorbid chronic health conditions that might independently lead to the receipt of informal care, as well as for sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, gender, net worth) and the availability of informal caregivers (having a spouse present, having a living adult child). The chronic (self-reported) health conditions controlled for in the study included heart disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, lung disease, urinary incontinence, cancer, and arthritis. In addition, we controlled for the presence of visual impairment (corrected eyesight reported as fair, poor, or legally blind) and hearing impairment (corrected hearing reported as fair or poor). Finally, we also adjusted for the presence of cognitive impairment consistent with dementia as measured by a previously validated cognitive status instrument

(19,

48).

Although we examined the bivariate relationship of depressive symptoms with limitations in activities of daily living and in instrumental activities of daily living, we did not control for the number of those limitations in the multivariate regression analysis. Limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living were considered the mediating factors between depressive symptoms and informal caregiving (i.e., depressive symptoms led to the limitations, which, in turn, led to the receipt of informal caregiving to address the limitations), so controlling for these variables in the regression analysis would result in an underestimation of the true effect of depressive symptoms on the quantity of informal caregiving

(49). To control for limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living related to other chronic conditions besides depression, we included variables in the analysis to indicate the presence of these coexisting illnesses.

Calculating the Cost of Informal Care

The “opportunity cost” associated with informal caregiving for activities of daily living is often estimated by using the average wage for a home health aide

(36,

37), on the basis of the assumption that this wage represents the cost of purchasing similar caregiving activities in the market. We used this method to estimate the yearly cost of informal caregiving for respondents in each depressive symptom category by multiplying the 2000 median national wage for a home health aide ($8.23 per hour

[50]) by the adjusted weekly hours of care and then multiplying by 52 (weeks per year). We then used the national prevalence estimates of depressive symptoms available from the AHEAD study to determine an estimate of the yearly national cost of informal caregiving associated with depressive symptoms. To provide a reasonable range of costs for informal caregiving, we performed a sensitivity analysis for annual national caregiving costs using the 10th percentile wage for a home health aide ($6.14 per hour) as a more conservative estimate of the opportunity cost of caregiver time and the 90th percentile wage ($11.93 per hour) as a more generous estimate

(50).

Data Analysis

Descriptive data were analyzed with the Wald test and with the design-based F test

(51), a modification of the Pearson chi-square test. The results of both statistical tests were adjusted to account for the complex sampling design of the AHEAD study.

Because a substantial proportion of the respondents received no informal care and because the distribution of hours among recipients of care was highly skewed, we constructed a two-part multivariate regression model using both logistic and ordinary least squares regression

(52,

53). Details of the use of this analysis strategy with AHEAD caregiving data have been published previously

(19,

47).

Analyses were weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design (stratification, clustering, and nonresponse) of the AHEAD study

(40). We tested for significant interaction effects among the independent variables and performed regression diagnostics to check for influential observations and heteroscedasticity in the residuals. All analyses were performed by using STATA Statistical Software: release 7.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.). The Health and Retirement Study/AHEAD study was approved by an institutional review board at the University of Michigan. The data used for this analysis contained no unique identifiers, so respondent anonymity was maintained.

Results

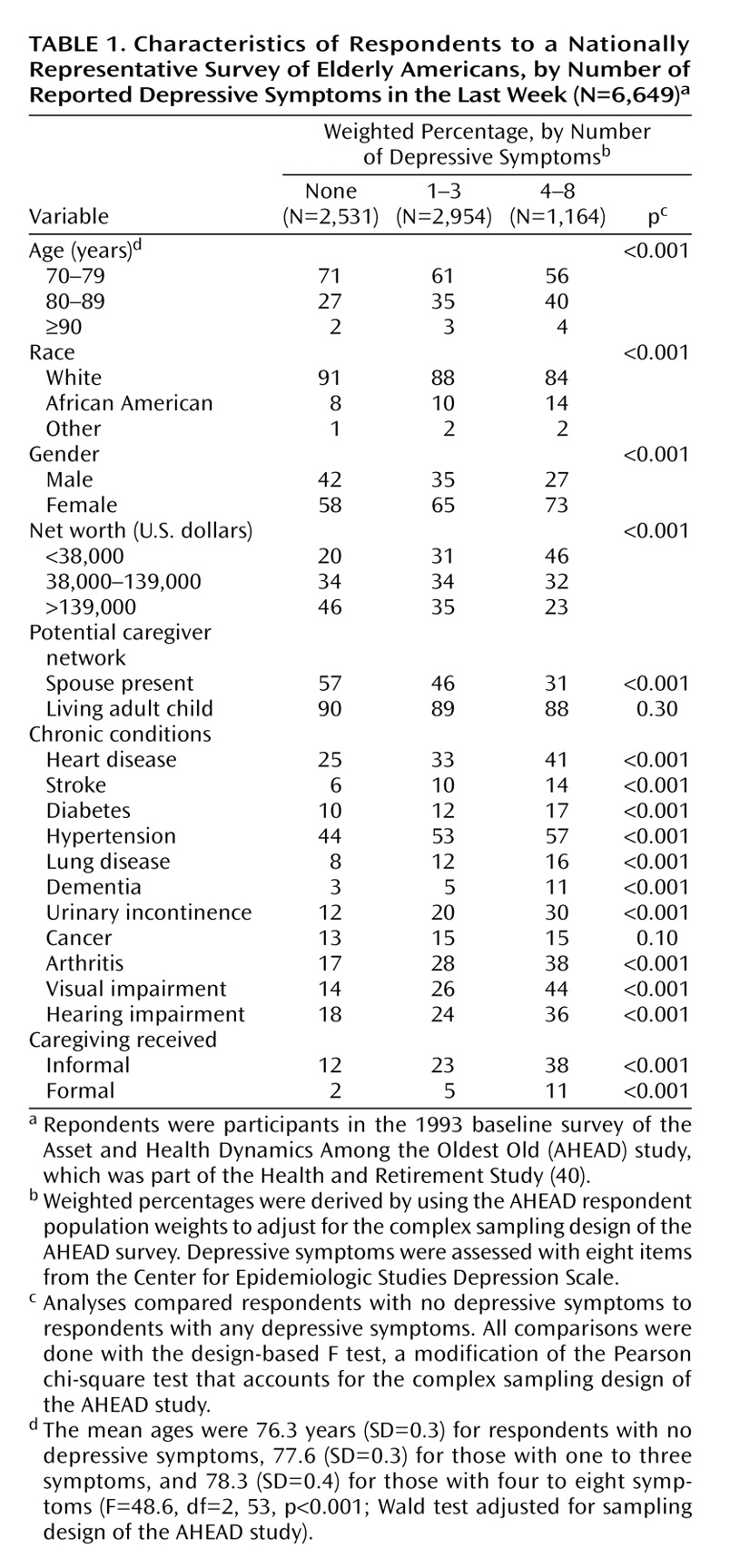

Descriptive information about the study sample is shown in

Table 1. About 44% of the respondents reported one to three depressive symptoms in the last week, and 18% reported four to eight depressive symptoms. Compared to respondents without depressive symptoms, respondents with depressive symptoms were older; more likely to be African American, female, and have low net worth; and less likely to be living with a spouse (p<0.001, design-based F test). The presence of depressive symptoms was associated with significantly higher rates of all chronic medical conditions (p<0.001, design-based F test) except cancer (p=0.10, design-based F test). Depressive symptoms were also related to significantly higher rates of both informal and formal (paid) caregiving (p<0.001, design-based F test).

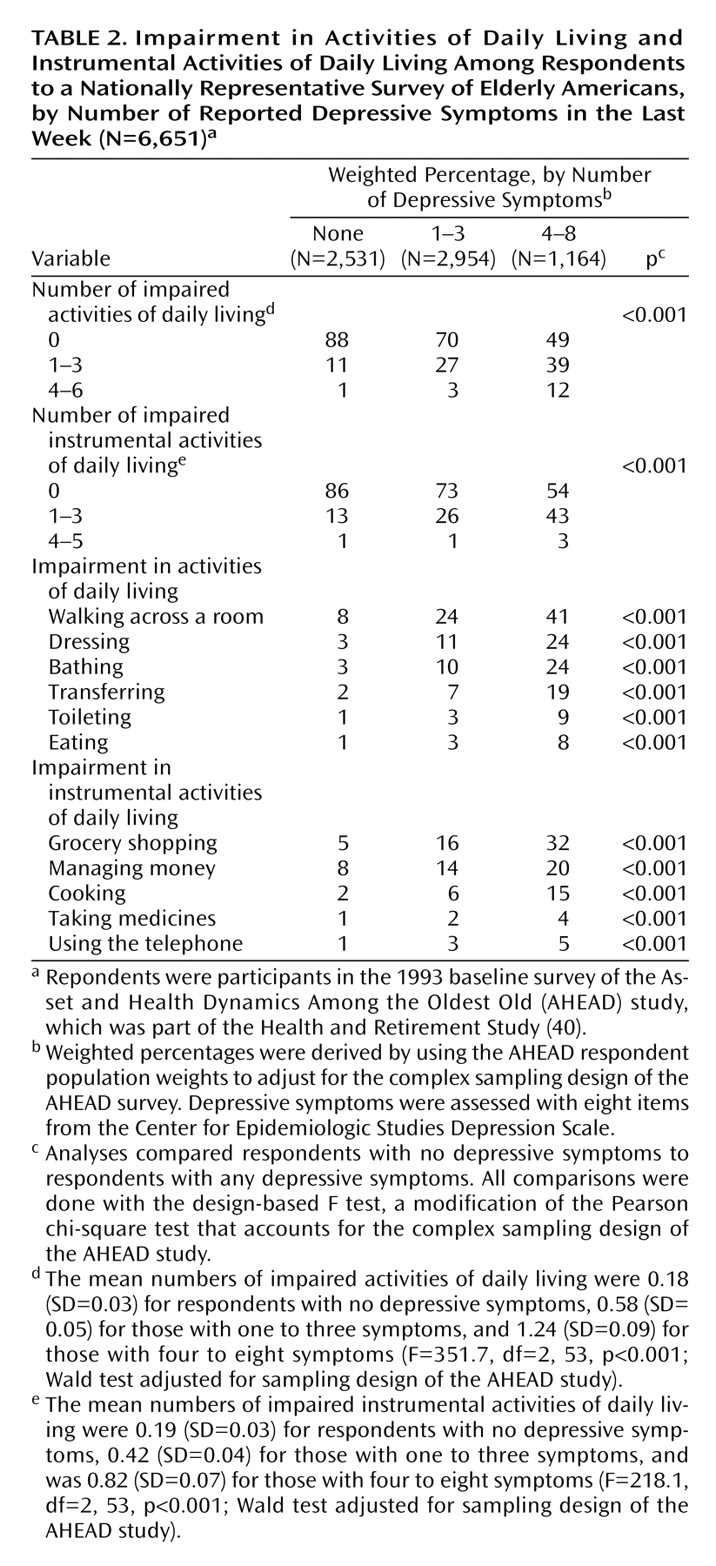

Table 2 shows rates of limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, by depressive symptom category. The number of depressive symptoms was strongly associated with the number of limitations. Only 12% of the respondents without depressive symptoms reported one or more limitations in activities of daily living (group mean of 0.18 limitations), while 51% of the respondents with four to eight depressive symptoms reported at least one limitation (group mean of 1.24 limitations) (p<0.001, design-based F test). A similar pattern was found for limitations in instrumental activities of daily living.

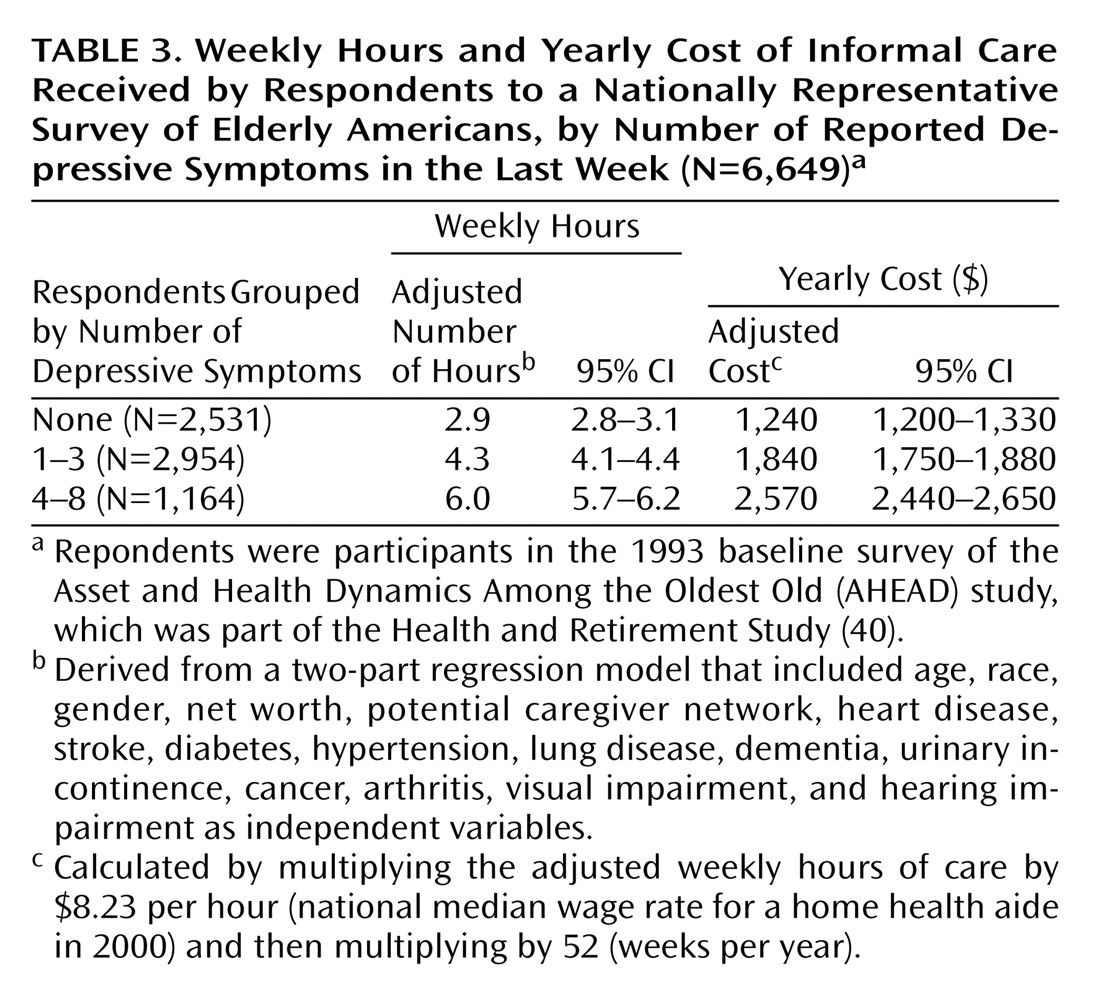

Results for informal caregiving hours and cost, after adjustment for all other covariates by using the two-part regression analysis, are shown in

Table 3. Elderly individuals with no depressive symptoms received, on average, 2.9 hours per week of informal care, while those with one to three symptoms received 4.3 hours per week (or 1.4

additional hours of informal care, compared to those with no symptoms), and those with four to eight symptoms received 6.0 hours per week (or 3.1

additional hours of informal care, compared to those with no symptoms) (p<0.001, Wald test).

We tested the interaction of depressive symptoms and each of the other 11 chronic conditions for a significant effect on caregiving hours. None of these interaction terms achieved statistical significance in both parts of the two-part regression model. Inclusion of the interaction terms resulted in no significant effects on the estimate of caregiving hours for any of the depressive symptom categories.

In calculations that used the 2000 median home health aide wage ($8.23 per hour), the 1.4 additional weekly hours of informal care for respondents with one to three symptoms resulted in an additional yearly informal caregiving cost of about $600 per person ($8.23/hour × 1.4 hours/week × 52 weeks/year). For respondents with four to eight depressive symptoms, the additional yearly informal caregiving cost was about $1,330 per person.

Given the nationally representative sample of the AHEAD study, an estimate of the total informal caregiver time and cost associated with depressive symptoms among community-dwelling elderly individuals age 70 years or older in the United States could be calculated. Our results suggested that approximately 8.3 million older individuals had one to three depressive symptoms and that 3.1 million individuals had four to eight depressive symptoms. Multiplying these prevalence estimates by the additional cost per person yielded an additional yearly caregiving cost of about $5.0 billion for elderly persons with one to three depressive symptoms and $4.1 billion for elderly persons with four to eight depressive symptoms, for a total additional yearly caregiving cost in the United States of about $9.1 billion. By using the 10th percentile home health aide wage ($6.14 per hour) as an estimate of the cost of caregiver time, the total annual additional national cost would be about $6.8 billion; using the 90th percentile wage ($11.93 per hour) yielded an estimate of about $13.2 billion per year.

Discussion

This study of a nationally representative sample of older Americans confirmed that depressive symptoms are extremely common, are associated with significantly higher levels of disability, and are independently associated with higher levels of informal caregiving, even after adjustment for major coexisting chronic conditions. The additional hours of care found attributable to depressive symptoms in this study represent a significant time commitment for family members and, therefore, a significant societal economic cost.

The relationships among depressive symptoms, limitations in activities of daily living and in instrumental activities of daily living, and caregiving are likely complex. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and functional limitations, with depression at baseline associated with functional impairment at follow-up and functional limitations at baseline associated with depression at follow-up

(4,

54–58). Depression and poor physical functioning may be mutually reinforcing, with each making the other more likely and each increasing the likelihood of poor outcomes (including the need for caregiving) among older individuals

(4).

The association between depressive symptoms and functional limitations that we found in the AHEAD study was similar to that seen in earlier studies, with a continuous positive relationship between depressive symptoms and disability. Similarly, we found that informal care hours increased with increases in the number of depressive symptoms. In the AHEAD study, respondents with a score of 4 or more on the 8-item CES-D Scale, who had the highest probability of meeting the criteria for major depression, also had the highest levels of caregiving. It is interesting to note that the quantity of caregiving remained relatively constant for individuals with four to eight depressive symptoms (data not shown), suggesting that this cutoff point may indeed be useful in screening for major depression.

The fact that women were more likely than men to report depressive symptoms may put women at especially high risk of having unmet needs for informal care and social support. In a previous study, we showed that women with functional limitations received significantly fewer hours of informal care than men with similar levels of impairment

(59). This difference was related to women’s greater likelihood of living alone, but even women who lived with a spouse received significantly less care than was provided to men with functional limitations. Older women were also much more likely than men to have low net worth, which perhaps made it more difficult to obtain paid home care or other necessary medical services. Given these realities, clinicians should be especially vigilant in determining whether older women with depressive symptoms have adequate levels of social support.

We note several potential limitations of this study. First, we used methods that likely led to conservative estimates of informal caregiving time and cost. The AHEAD data include only caregiving that was provided for help with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. The time required for caregivers to perform other activities that might be associated with depressive symptoms, such as transportation to physician appointments or providing expressive rather than instrumental support, were not included in the analysis. In addition, negative effects on paid employment, such as increased absenteeism or taking early retirement because of caregiving responsibilities, were not accounted for. Caregiving may cause negative health effects

(60) or even increased mortality

(61) among caregivers; the costs related to such possible outcomes were not included in this study. However, even with the conservative measures and the low-range opportunity cost estimate we used, the estimated national annual cost associated with caregiving for depressive symptoms still reached about $7 billion per year.

Second, as with all observational studies, the possibility existed that a variable omitted from our analysis (e.g., another comorbidity) that was correlated with both the presence of depressive symptoms and the presence of informal caregiving was the “true cause” of the higher rate of caregiving for respondents with depressive symptoms. However, we controlled for key sociodemographic measures, the extent of the potential caregiver network, and the presence of common comorbidities that have been shown to influence the level of informal care for older individuals. Since our estimate of the time and cost associated with informal caregiving for depressive symptoms was a conservative one, it is unlikely that we significantly overestimated the cost of caregiving for depression because we omitted a variable. Finally, it should also be noted that the wage of a home health aide might underestimate the societal economic cost of informal caregiving if the quality and effectiveness of paid home care were lower than that of the care provided by a committed spouse or child and since other costs associated with paid home care (e.g., administrative costs and employee benefits) were not included in the wage rate.

Clinicians and policy makers should be cognizant of the potential increased need for informal caregiving among older individuals with depressive symptoms. Clinicians should inquire about the adequacy of social support for their elderly patients with depressive symptoms and should also be alert to potential caregiver “burden” among the family members who provide care (and who are themselves likely to be elderly). When making decisions regarding the allocation of medical resources, policy makers should consider the substantial costs of informal caregiving for depressive symptoms, in addition to the clear effects of those symptoms on individuals’ independent functioning and quality of life. Including the costs of caregiving for older individuals with depressive symptoms will further improve the already favorable cost-effectiveness ratio of many broad-based collaborative interventions for the treatment of depression

(62,

63).