Genetic factors are important in determining the complex smoking phenotype, as shown by twin studies showing that genes partially confer susceptibility to nicotine dependence

(1). As well as two genome scans

(2,

3), there have been a number of tests of candidate genes

(4), including the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (SERT)

(4–

9). The SERT promoter region is a 44-base-pair insertion/deletion polymorphism that was originally shown to be associated with anxiety-related personality traits

(10). Indeed, an interaction of the short promoter polymorphism, anxiety-related personality traits, and smoking was observed in two studies

(7,

8). Conversely, in a Japanese study it was the long promoter variant that was observed to be associated with smoking

(6,

9).

We have now recruited a new group of 330 families, including 244 past and present smokers, in the framework of our continuing studies of normal personality

(11), positioning us to validate previous studies showing an interaction between SERT, personality traits, and smoking behavior

(7,

8). Toward this end, we genotyped this group for two SERT polymorphisms, the serotonin (5-HT) transporter linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR) and an intronic variable-number-of-tandem-repeats region (VNTR)

(12). Both common repeats of the VNTR are purported to increase transcription of this gene

(13). The association between smoking and SERT was analyzed both by using a case-control design and by a more robust family-based approach. Scoring allelic transmission in families

(14,

15) allowed us to test association in this heterogeneous group by using both categorical and quantitative definitions of smoking.

Results

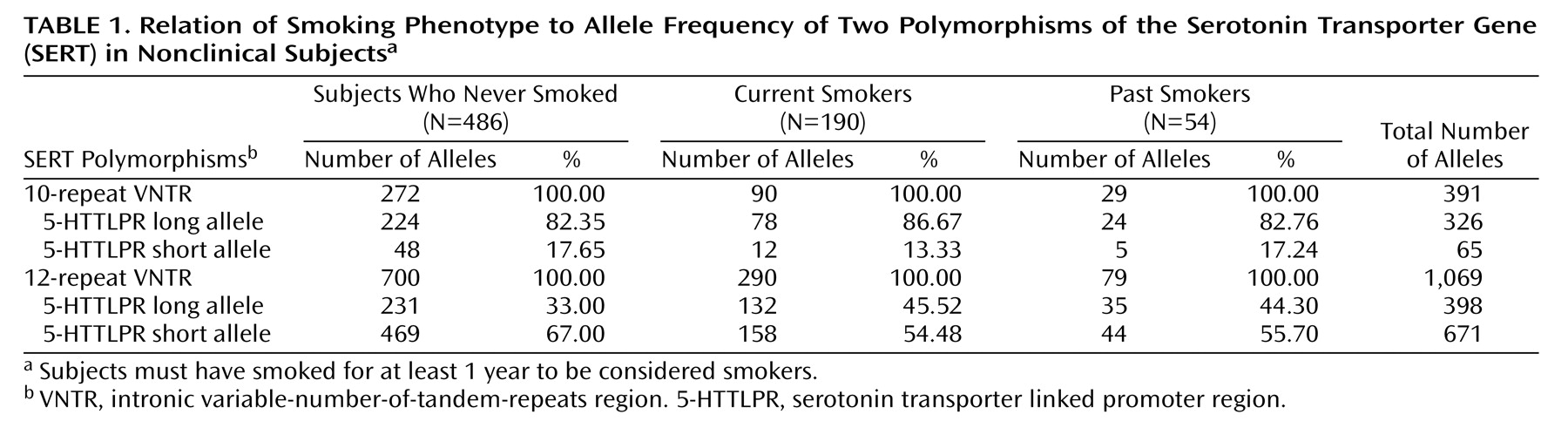

In the first analysis we used a population-based case-control design to examine the association between SERT polymorphisms (5-HTTLPR and intronic VNTR) and the smoking phenotype (

Table 1). There was a significant excess of the 5-HTTLPR long allele with the 12-repeat VNTR (Pearson χ

2=15.57, df=2, p=0.0004) in both current and past smokers, compared to people who had never smoked (“never smokers”). When ever smokers (past and current) were compared to never smokers (data not shown), there was also a significant excess of the 5-HTTLPR long allele with the 12-repeat VNTR (χ

2=14.38, df=1, p=0.0001), and the estimated risk of these polymorphisms occurring together in ever smokers was 1.37 (95% confidence interval, 1.17–1.61).

We also stratified the smokers by scores on the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and by the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Within the group of current smokers, no association was observed between Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire score (1–5 versus >5) and SERT (10-repeat VNTR: χ2=0.61, df=1, n.s.; 12-repeat VNTR: χ2=0.05, df=1, n.s.; with either the short or long 5-HTTLPR allele, respectively). Additionally, no association was observed between the number of cigarettes smoked per day (0–5, 6–15, >15) and SERT (10-repeat VNTR: χ2=0.58, df=2, n.s.; 12-repeat VNTR: χ2=2.40, df=2, n.s.; with either the short or long 5-HTTLPR allele, respectively).

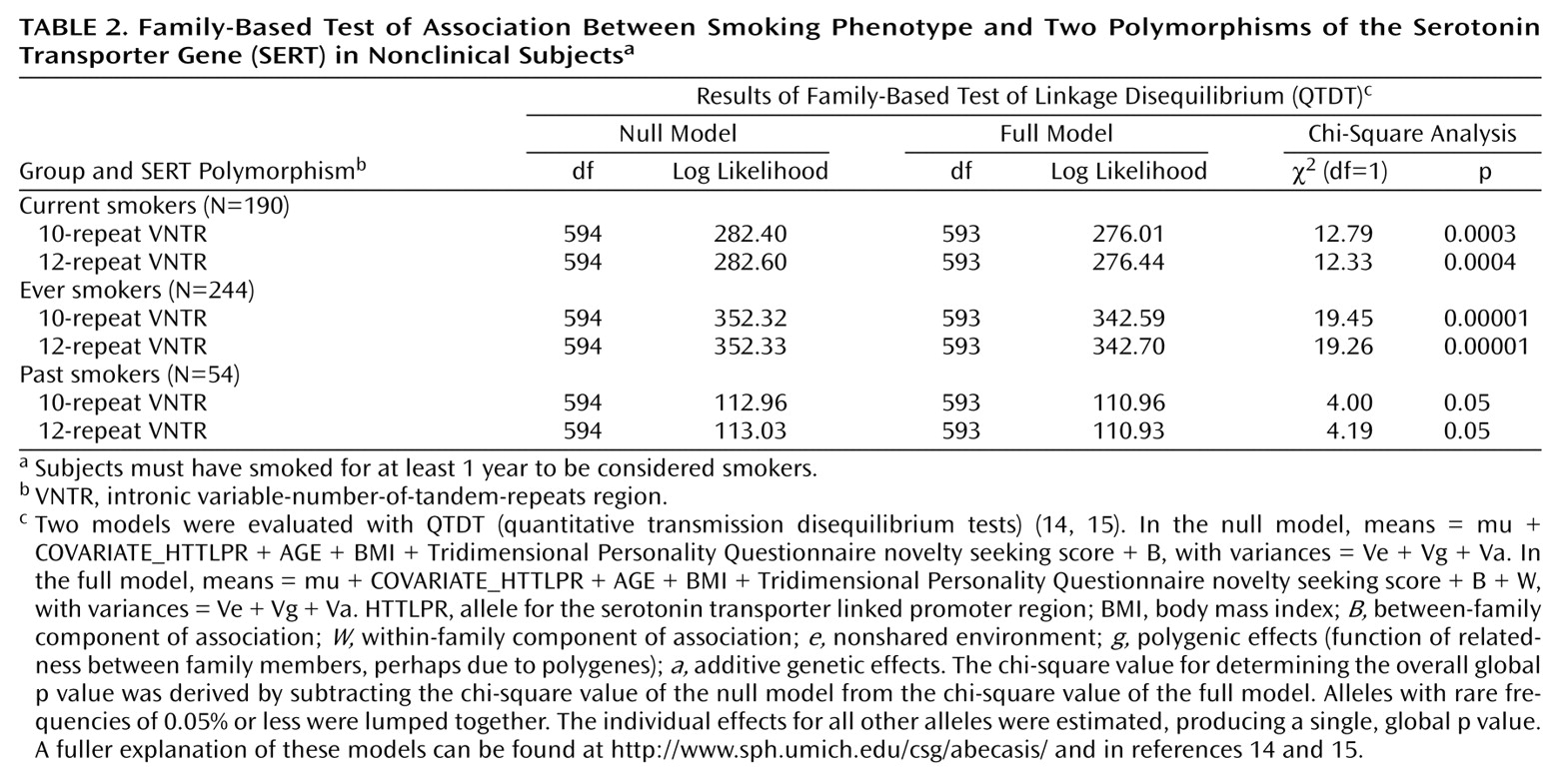

Since population-based case-control designs are prone to errors due to population stratification, we also examined these findings using a robust family-based QTDT analysis. The results from the population design were confirmed in the family-based analysis (

Table 2) for current smokers, ever smokers, and past smokers. Again, no association was observed between SERT VNTR (5-HTTLPR and age were covariates in the QTDT analysis) and the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire score (χ

2=0.03, df=1, n.s.) or number of cigarettes smoked per day (χ

2=1.41, df=1, n.s.). A marked difference in score on novelty seeking between smokers and nonsmokers (see next paragraph) provided the rationale for using this personality trait as a covariate in the QTDT family-based test of association. Body mass index was also introduced as a covariate, suggested by the association between smoking and eating

(19). Both novelty seeking and body mass index increased the levels of significance, whereas when sex was entered as a covariate there was no change in significance levels.

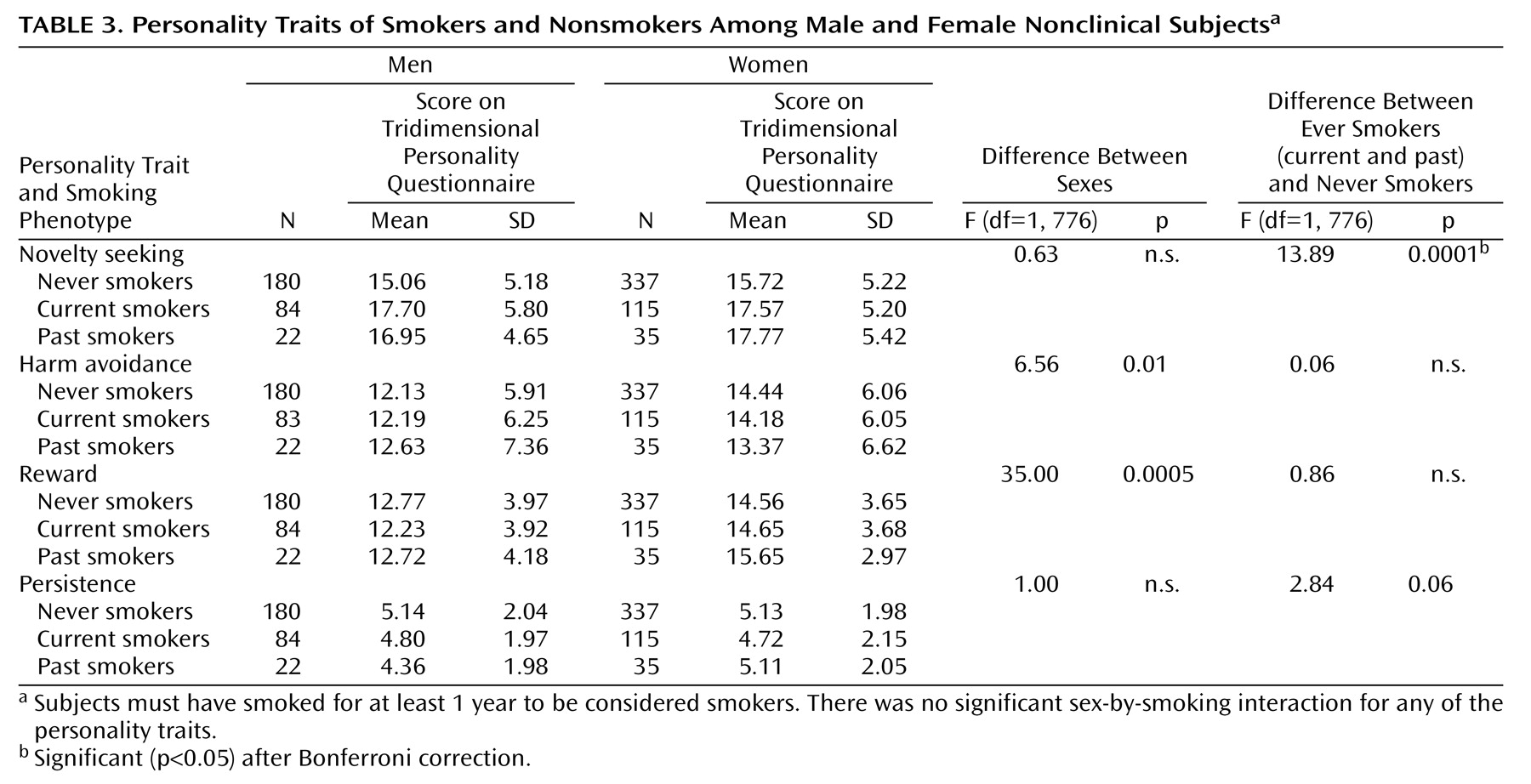

Numerous reports have suggested differences in personality traits measured by self-report questionnaires between smokers and nonsmokers, and

Table 3 presents a comparison of personality factors in nonsmokers, current smokers, and past smokers. Current smokers and past smokers scored significantly higher on the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire trait of novelty seeking than did never smokers. There were no significant differences between past and current smokers. Smokers did not differ from never smokers on either the reward or harm avoidance measure. Smokers scored nonsignificantly lower on persistence. As observed previously in the Israeli population

(20), the women scored higher than the men on both harm avoidance and reward, but we found no significant interaction between sex and smoking phenotype regarding the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire temperament factors. Both male and female smokers scored higher on novelty seeking than sex-matched never smokers according to analysis of variance.

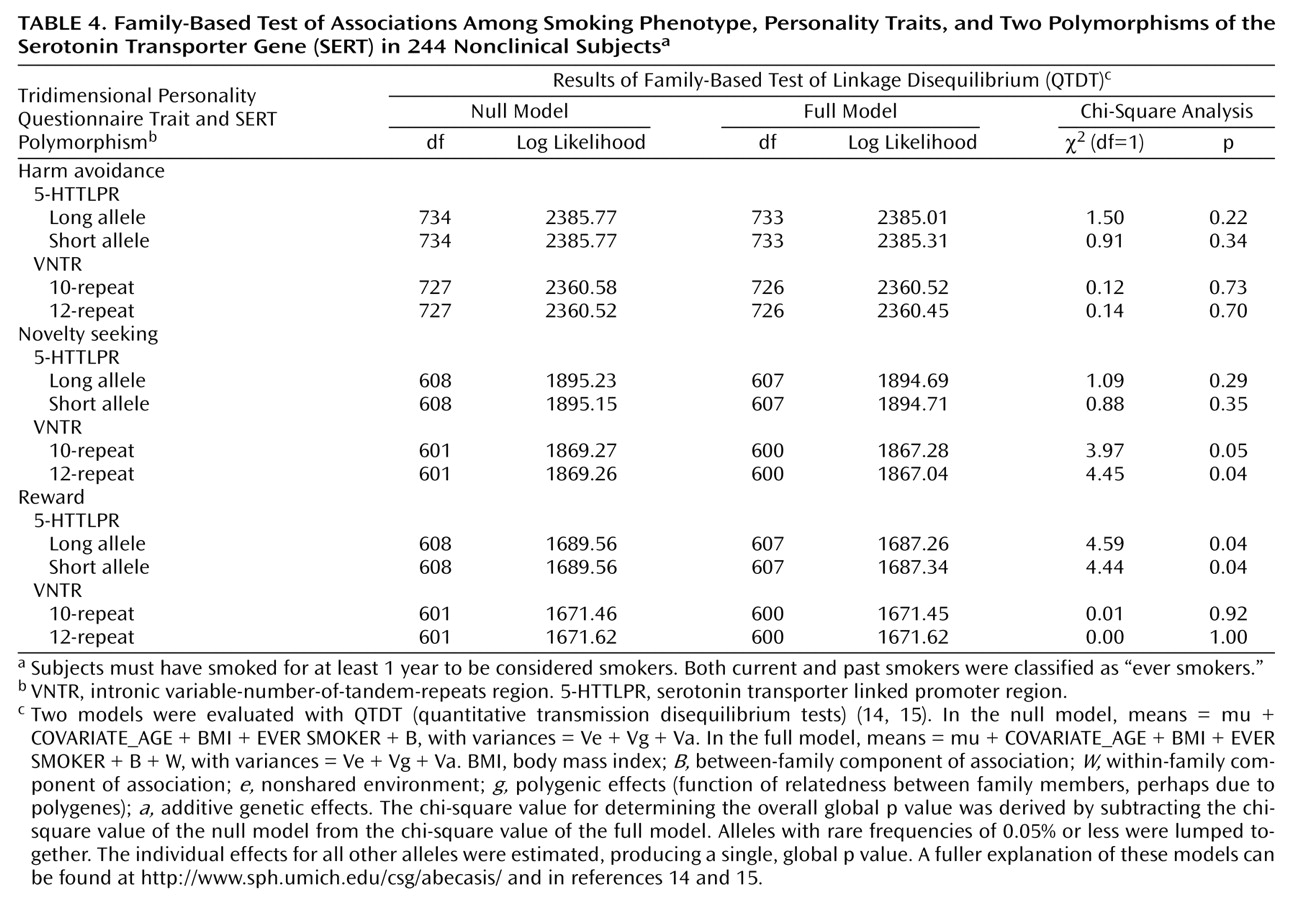

We next examined the relationships among the SERT polymorphisms, personality traits, and smoking phenotype. Although a strong association was observed between the SERT variants and the smoking phenotype (

Table 1), only weak relationships were observed between the polymorphisms and personality traits according to the QTDT family-based analysis (

Table 4). No association was detected in this study group between the SERT polymorphisms and harm avoidance, whereas a weak but significant association was observed between novelty seeking and the VNTR polymorphism. Additionally, a weak association was observed between the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and reward. However, none of these associations between the SERT polymorphisms and the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire personality traits was significant following Bonferroni correction.

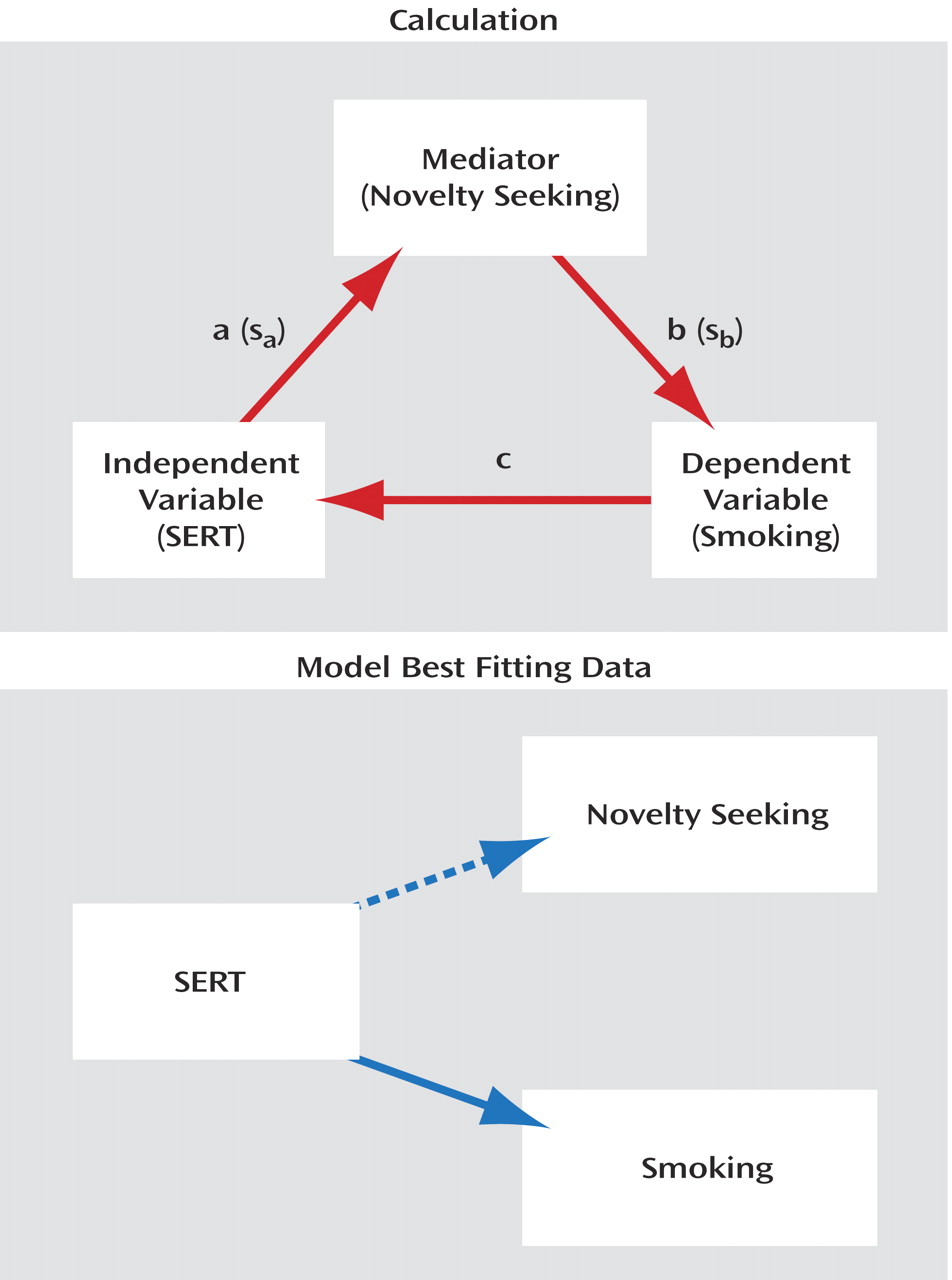

To test the hypothesis that novelty seeking mediates the effect of SERT on smoking, we used mediation analysis as described by Baron and Kenny

(21) and the Sobel method

(22) for significance, testing whether the mediator (novelty seeking) carries the influence of the independent variable (SERT) to smoking. The Sobel test provided no evidence for the hypothesis that novelty seeking indirectly mediates the effect of SERT on smoking (t=1.18, df=2, p=0.23). The model shown in the lower part of

Figure 1 appears to best fit the data: SERT genotype independently influences smoking phenotype and, more weakly, novelty seeking.

Discussion

The main finding of the current study was a highly significant association between SERT and smoking. The long 5-HTTLPR allele with the 12-repeat VNTR conferred modest risk for smoking according to both case-control analysis and the more robust family-based design. Two previous Japanese studies

(6,

9) also showed an association between the long 5-HTTLPR allele and smoking by means of a case-control design.

Many North American studies have shown that tobacco use is associated with several related personality features among adolescents and adults, including extraversion, impulsivity, risk taking, sensation seeking, monotony avoidance, novelty seeking and rebelliousness, and psychopathic and antisocial personality

(23). Additionally, longitudinal studies have revealed that many of the aforementioned personality characteristics predict tobacco use

(24). However, anxiety-related personality traits are also predictors of smoking behavior

(25). For example, panic attacks are associated with greater risk of cigarette smoking, and neuroticism may play an essential role in this relationship

(26). It appears that no single personality type generates risk for this complex phenotype, and either extraversion and neuroticism, depending on the cultural and genetic milieu, may contribute to initiation and persistence of smoking. The most notable difference between the current investigation and the American studies

(5,

7,

8) is ethnicity and cultural setting, although, it should be noted, three different personality inventories were also employed, the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire

(17), Eysenck Personality Inventory

(27), and NEO Personality Inventory, Revised

(28). We believe it is unlikely that a difference due to the specific personality questionnaire used explains the contrasting results, since the personality traits of novelty seeking and harm avoidance and the NEO equivalents (extraversion and neuroticism) correlate well in most studies

(29). It is not surprising that the particulars of the interaction between heritable personality traits, a complex behavioral phenotype such as smoking, and SERT differ across cultural and ethnic categories. It is intriguing that in two North American studies

(5,

7,

8), in which smokers scored high on neuroticism, the short promoter variant showed an association with this phenotype, whereas in an Israeli population, in which smokers scored high on extraversion or sensation seeking, the long promoter variant was associated with smoking. Thus, the apparently opposing findings regarding which SERT promoter region allele is associated with smoking in two diverse cultural and ethnic groups are resolved by considering which personality trait (novelty/sensation seeking versus neuroticism) characterizes smokers. The role of the short allele in the North American study and the involvement of the long allele in the Israeli study therefore make biological and psychological sense.

The degree of nicotine dependence is unlikely to account for the particular SERT variant associated with smoking, since smoking habits vary considerably across studies without regard to genotype

(5–

9). The study by Lerman et al.

(5,

7), which showed an association with the short SERT variant, included smokers who had smoked at least five cigarettes per day for at least 1 year and were likely interested in quitting. Hu et al.

(8) recruited subjects who had smoked an average of 20 cigarettes per day for an average of 15 years, and in this group an association with the short SERT genotype was observed. The Japanese subjects consumed more than 25 cigarettes daily, and an association with the long SERT variant was observed. In the current investigation, the subjects smoked an average of 13 cigarettes daily and there were few “heavy” smokers, and again, an association with the long variant was observed.

We used a broad definition of smoking and studied a range of smoking phenotypes, raising the question of whether subjects within this heterogeneous group can be meaningfully compared. In the genetic analysis, however, the smoking phenotype was examined not only as a categorical trait but also as a quantitative trait. The powerful quantitative approach allowed us to test in the genetic model the degree of smoking dependence measured by number of cigarettes per day and score on the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. However, neither quantitative measure showed any association with SERT. The highly significant association observed between the categorical definition of smoking and SERT, irrespective of dependence, suggests that this gene is more involved in the initiation of smoking than in its persistence or the level of dependence.

Short-term administration of nicotine releases serotonin, whereas long-term treatment depletes brain serotonin, and there is strong evidence that serotonergic tone plays a permissive role in the expression of nicotine’s effects

(30). Subjects with low serotonergic tone due to the presence of the long promoter variant may be particularly sensitive to the serotonin-releasing effects of short-term nicotine administration and thus at greater risk of developing dependence on cigarettes. Once initiated, smoking will further reduce serotonin levels, thus exacerbating the dependence on nicotine in subjects with a more transcriptionally efficient transporter gene.

Similar to other addictive drugs, nicotine is thought to affect the brain’s dopaminergic reward system, which includes parts of the nucleus accumbens and amygdala

(31), and it is therefore of some interest that we observed in the current study a weak association between the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire reward score, the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, and smoking phenotype. Two previous studies

(32,

33) demonstrated an association between polymorphisms affecting the 5-HT

2C receptor and the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire reward score, and some animal data

(34) also support involvement of the 5-HT

2C receptor in mediating mesolimbic dopamine functioning. Indeed, serotonergic activity has a dual effect on stimulation of the brain reward system in rats

(35). Although the brain reward system is often associated with dopaminergic activity, key elements for the short-term reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse involve other neurotransmitters, such as opioid peptides, γ-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, and serotonin

(36).

In the present study, only a weak association was observed between novelty seeking and SERT, principally with the intronic VNTR, and despite the evidence that impulsive behavior is a risk factor for smoking in the Israeli population we studied, mediation analysis

(20,

21) carried out on the current data does not support the hypothesis that novelty seeking mediates the effect of SERT on smoking. SERT independently contributes weakly to novelty seeking and more strongly to the smoking phenotype. Further studies across cultural and ethnic groups are required to clarify the behavioral pathways that mediate the effect of SERT on smoking.