Meta-analytic techniques have been instrumental in the synthesis of the enormous literature on cognitive functioning in schizophrenia. A meta-analytic approach has several advantages (

2). First, by quantitatively combining the results of a number of studies, the power of statistical testing is increased substantially. Second, studies are differentially weighted by sample size. Finally, by extracting information quantitatively from existing studies, meta-analysis allows us to examine more precisely the influence of potential moderators on effect size.

Recent meta-analyses of specific cognitive domains and measures in schizophrenia have highlighted a processing speed deficit as central to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia (

3,

4). Processing speed refers to the number of correct responses an individual is able to make during a task within a given amount of time. Digit symbol coding tasks are ideally suited to measuring this ability, for which participants are required to correctly substitute symbols and digits using a key under timed conditions (

5). Because of their ease of use and data from recent meta-analyses suggesting that they might be useful in clinical settings for screening or for assessment of treatment effects in schizophrenia patients (

3), tests of this type have been used increasingly in research. This practice has produced additional information that is eligible for inclusion in meta-analyses focusing on processing speed.

The goals of this study were twofold. The first goal was to extend the findings of Dickinson and colleagues (

3) and of other meta-analyses that have shown a pronounced impairment in processing speed by incorporating recent reports of studies that used coding tasks. The second goal was to closely examine the role of study characteristics as potential moderators of coding task performance. Cognitive performance is susceptible to the influence of factors such as medication effects, illness severity, and research design. Consequently, it is important to carefully consider the role of these factors in mediating any apparent impairment in performance.

Discussion

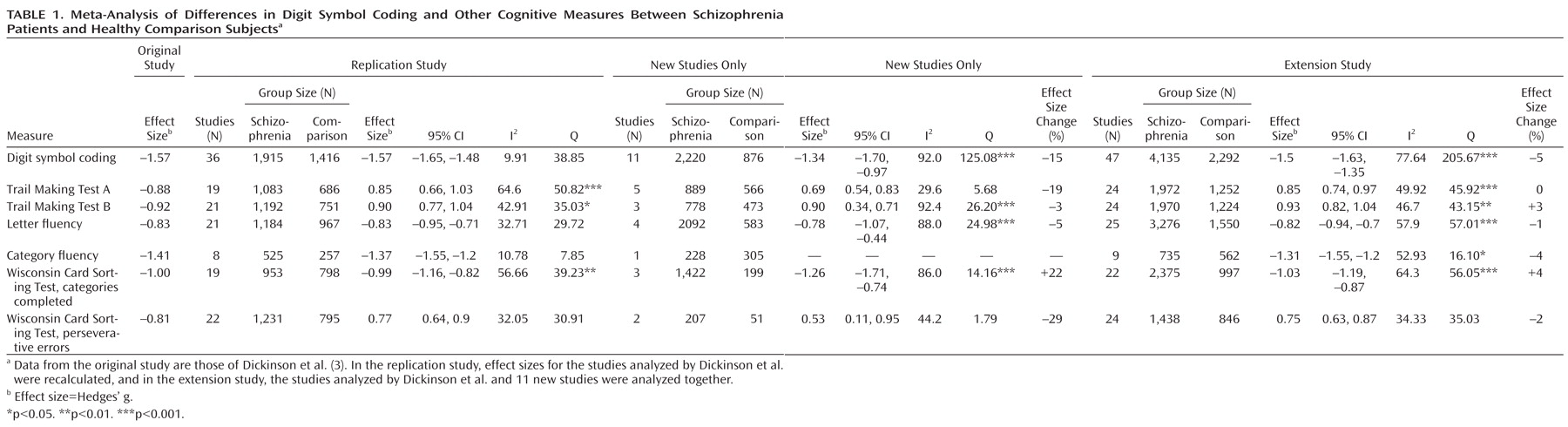

A number of meta-analyses have found that the effect size of digit symbol coding tasks in schizophrenia is significantly larger than the effects of other cognitive measures (

3,

4). This study successfully replicated this finding, supporting the assertion by Dickinson et al. (

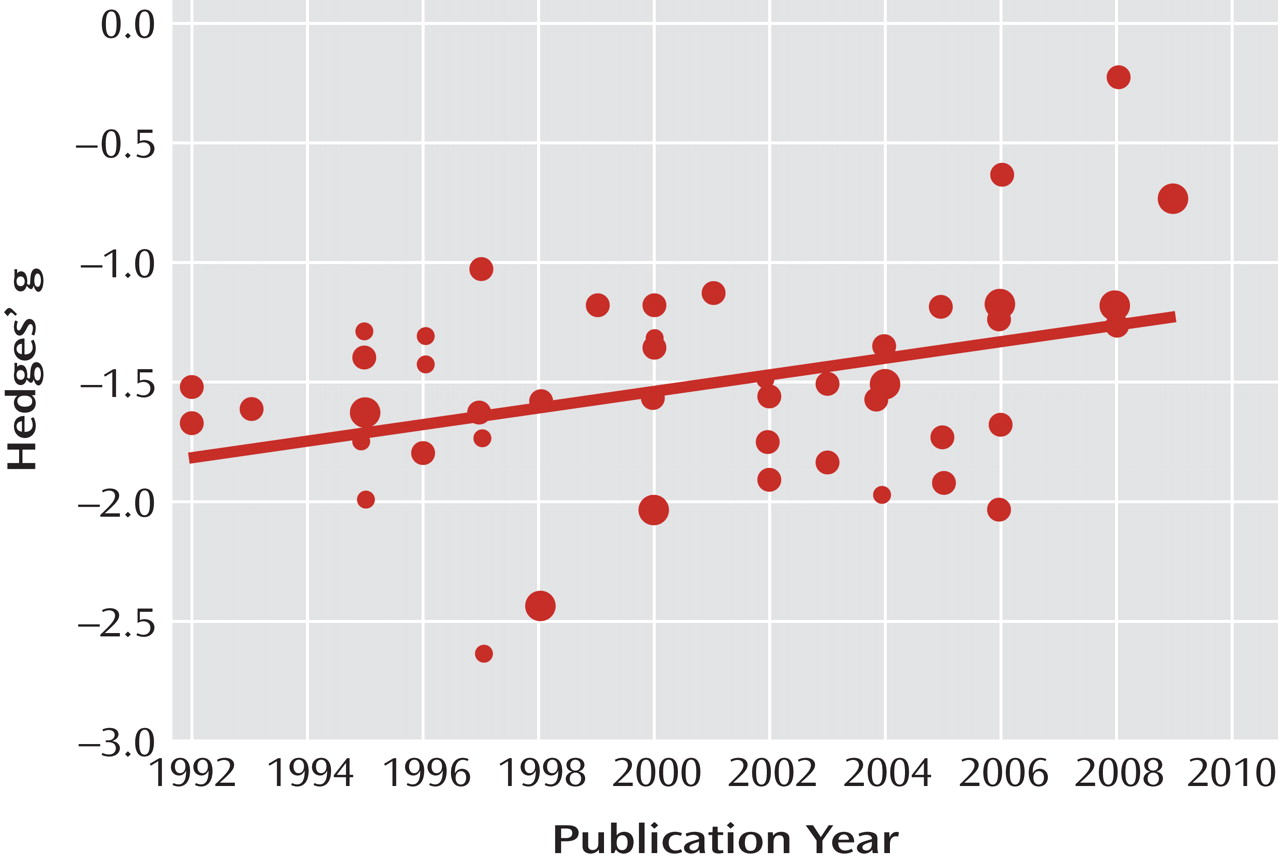

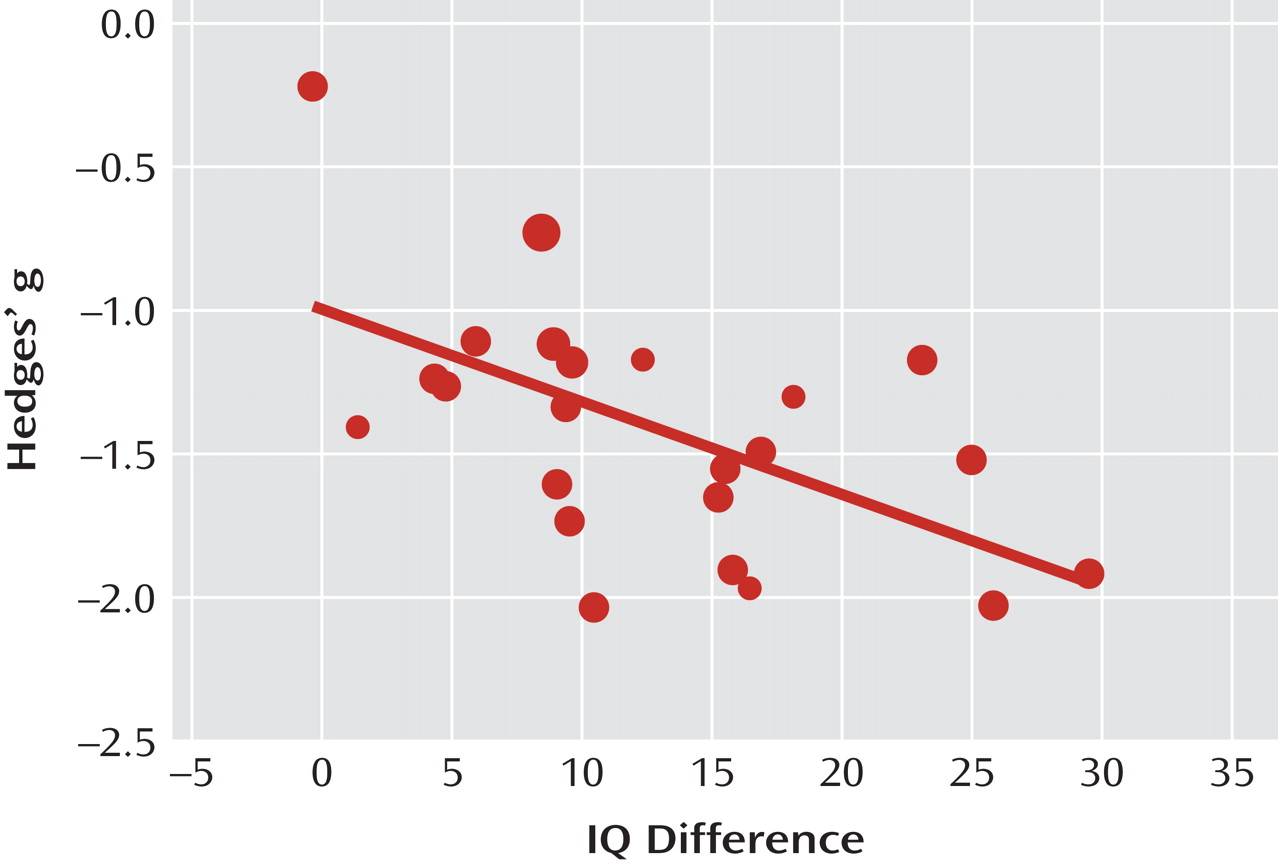

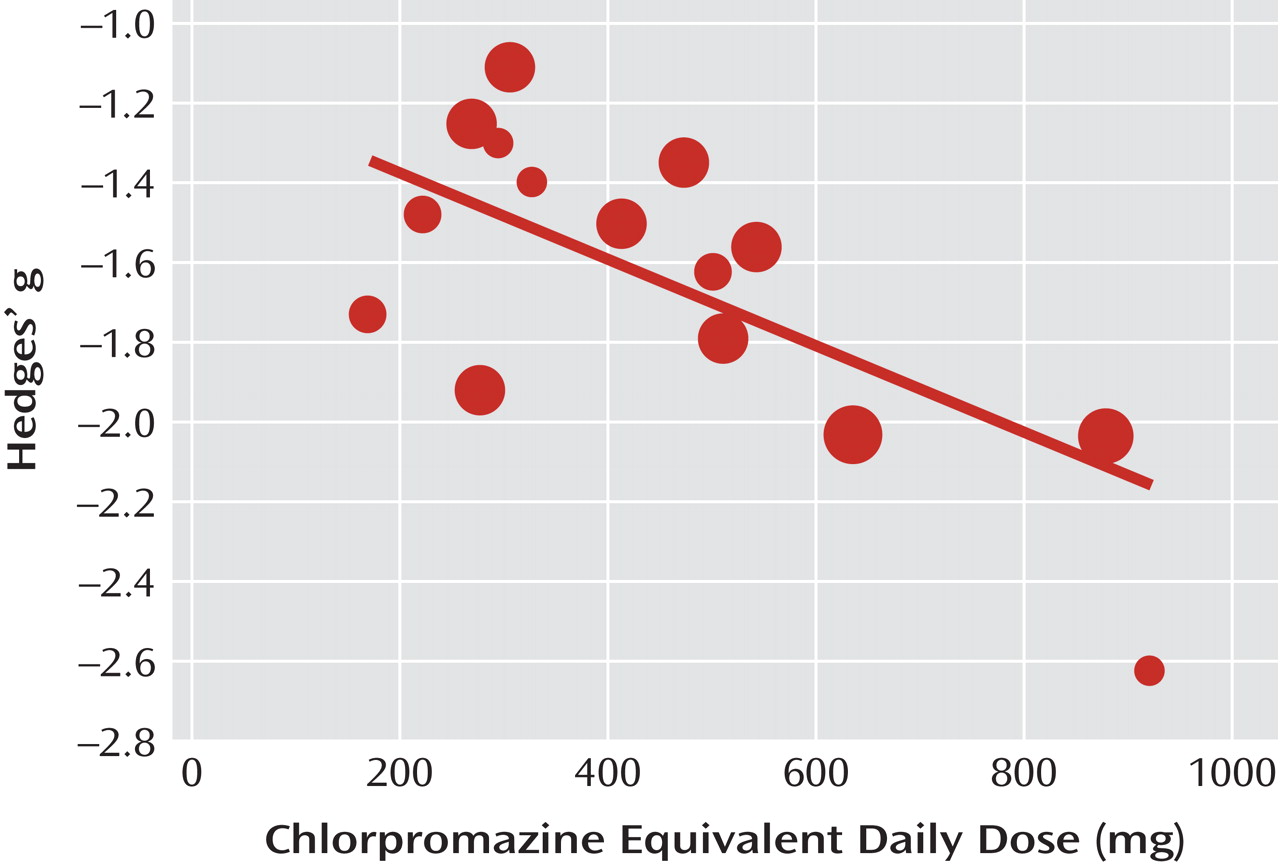

3) that a processing speed impairment is a "central feature of the cognitive deficit in schizophrenia" (p. 1). However, the addition of 11 new studies to the meta-analysis suggested an alternative interpretation of this result. The studies included in the analysis comprised several types of study design, and by utilizing these features we were able to closely examine factors that might modify the relationship between schizophrenia and coding task performance. We found that coding task effect size varied as a function of publication year, IQ difference between comparison and schizophrenia samples, and chlorpromazine equivalent daily dose. Because of the confounding influence of these moderator variables, it is possible that previous meta-analyses overestimated the effect size for coding tasks. This implies that if the moderator variables were controlled for, then coding task performance might not stand out as being particularly impaired.

The strongest moderator variable relationship observed in our study was between chlorpromazine equivalent daily dose and coding task effect size, such that the higher the daily dose, the greater the impairment. Dickinson et al. (

3) found that the coding task effect size remained unchanged when they limited the analysis to neuroleptic-naive patients. However, as they acknowledged, that analysis consisted of only three studies, and the use of neuroleptics was limited in two of them. When we stratified our analysis by low compared with high neuroleptic daily dose, it resulted in a difference in effect size of 0.8, corresponding to a large effect (

63). These results indicate that antipsychotic dosage has a sizable impact on processing speed. It should be noted, however, that the moderator analysis suggests that even if medication effects were excluded, the remaining deficit in coding tasks in schizophrenia patients would still be substantial.

IQ was the other important moderating variable. While the moderating effect of IQ may seem relatively unsurprising given that subtest and full-scale IQ scores are correlated (

64), it is also an important finding. If substantial differences in IQ between comparison and schizophrenia samples are ignored, researchers may be at risk of interpreting a large effect size for a specific cognitive ability as a selective impairment when in fact it is artificially inflated by general impairment in IQ. However, our results indicate that a large deficit in coding task performance in patients with schizophrenia remains even if IQ is accounted for.

It is unclear why coding task effect sizes should be smaller the more recently an article has been published. This relationship could be underlain by several factors. First, it might be due to improvements in study design over time; for example, IQ matching between schizophrenia and comparison samples significantly predicts coding task effect size. Second, the effect of publication year could be explained by the moderating effect of medication, such that the two confounding factors interact. The extrapyramidal side effects of conventional antipsychotic medications are likely to impair psychomotor performance and are more likely to have been used in the earlier studies. Conversely, the newer atypical antipsychotic medications that are likely to have been used in a higher proportion of patients in the more recent studies are generally thought to induce fewer adverse psychomotor side effects (

65), although there is some evidence to suggest that atypical antipsychotics, in particular risperidone, may adversely affect working memory (

66–

68). Alternatively, different dosages of these medications may have been used over different periods. Unfortunately, detailed information on antipsychotic type was rarely reported.

It is possible that all these moderating variables overlap or are confounded in some way. For example, patients with lower IQ may also be on higher doses of medication because they have a more severe form of the disorder, or medication may adversely affect IQ (and digit symbol coding). Unfortunately, statistical methods for dealing with confounding in meta-analyses apart from stratification are not, to our knowledge, readily applicable.

The results of the moderator analysis conducted by Dickinson et al. (

3) differ slightly from our own, as we did not find moderating effects of age and chronicity. This could be a result of the disparate methods of analysis. There are two types of moderator analysis—subgroup and metaregression analyses. Dickinson et al. used the former type and used a median split to create groups. We applied the latter type, thus using the full range of data. Furthermore, in our metaregression analysis, a random-effects approach was implemented whereby the contribution of each study was weighted. Another reason for differences in results between the two studies is the addition of a significant amount of data in our study, which might have resulted in a change in the relationships between variables.

Impaired performance on category fluency measures was second to coding tasks and was followed by letter fluency; this pattern of results is also evident in other meta-analyses using these measures (

3,

4). These results complement other studies that show greater impairment for category fluency than for letter fluency (

69). Fluency is a complex measure of both processing speed and other distinct cognitive abilities (

70,

71). It is thought that impairment in executive control underlies poor performance in general on verbal fluency tests but that a specific compromise to the semantic store hinders performance on category fluency in schizophrenia (

69). Notably, the metaregression analyses did not reveal any significant moderator variables for either of the fluency tasks, or indeed for any of the other cognitive measures. This suggests that the effects for these measures are not subject to distortion by confounding factors.

These results should be viewed with the caveat that metaregression is a form of observational association and therefore cannot be used to make causal inferences about the data (

60). There may be confounding factors that underlie the relationships reported here. Moreover, given the sparse reporting of study characteristics, the metaregression analyses captured only some of the studies included in the meta-analyses. Despite these shortcomings, our results suggest that research investigating processing speed in schizophrenia should consider the effect of potential moderating factors. Another potential issue for this article is that the largest study included in the meta-analysis is the CATIE trial (

46). Inclusion of this study could be considered problematic as it used normative data rather than a comparison group in order to calculate effect sizes. The use of norms as opposed to comparison subjects is an ecologically valid approach and is used both in standard neuropsychological assessment and in research (

1). However, our sensitivity analysis demonstrated that inclusion of the CATIE study did not bias the results of the meta-analysis or the moderator analysis. Removing the CATIE study from the analysis did not substantially change the average effect size estimate of the meta-analysis, and the effect of year of publication remained statistically significant without CATIE.