The past 20 years have witnessed a resurgence in clinical, policy, and research efforts to reduce stigma attached to mental illness. The White House Conference on Mental Illness and the Surgeon General's first-ever report on mental health (

1), both in 1999, coalesced knowledge and fostered renewed action. These comprehensive assessments applauded the range and efficacy of existing treatments for mental illness brought by advances across the medical and social-behavioral sciences, particularly neuroscience. However, they also documented a “staggeringly low” rate of service use among those in need, a shortage of providers and resources, and continued alarming levels of prejudice and discrimination (

1, p. viii;

2).

After reviewing the scientic evidence, the Surgeon General concluded that the stigma attached to mental illness constituted the “primary barrier” to treatment and recovery (

1, p. viii). Stigma could be reduced, many believed, if people could be convinced that mental illnesses were “real” brain disorders and not volitional behaviors for which people should be blamed and punished. Many prominent reports emphasized scientic understanding as a way to reduce stigma. For example, the Surgeon General's report identied scientic research as “a potent weapon against stigma, one that forces skeptics to let go of misconceptions and stereotypes” (

1, p. 454). Stigma reduction, based in part on disseminating information on neurobiological causes, became a primary policy recommendation of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (

3) as well as of international efforts (

4). Finally, while not intended specifically as an antistigma effort, commercial advertisements provided information on psychiatric symptoms, brain-based etiologies, and specific psychopharmacological solutions. In fact, direct-to-consumer advertising involved more U.S. resources than all those dedicated to educational campaigns (e.g., over $92 million on Paxil in 2000 [

5]).

Deeply embedded in social and cultural norms, stigma includes prejudicial attitudes that discredit individuals, marking them as tainted and devalued (

6). For individuals, stigma produces discrimination in employment, housing, medical care, and social relationships (

7–9). Individuals with mental illness may be subjected to prejudice and discrimination from others (i.e., received stigma), and they may internalize feelings of devaluation (i.e., self-stigma [

10]). On a societal level, stigma has been implicated in low service use, inadequate funding for mental health research and treatment (i.e., institutional stigma), and the “courtesy” stigma attached to families, providers, and mental health treatment systems and research (

11–13). Public stigma reflects a larger social and cultural context of negative community-based attitudes, beliefs, and predispositions that shape informal, professional, and institutional responses.

Antistigma efforts in recent years have often been predicated on the assumption that neuroscience offers the most effective tool to reduce prejudice and discrimination. Thus, NAMI's Campaign to End Discrimination sought to improve public understanding of neurobiological bases of mental illness, facilitating treatment-seeking and lessening stigma. Over the past decade, the American public has been exposed to symptoms, biochemical etio-logical theories, and the basic argument that mental illnesses are diseases, no different from others amenable to effective medical treatment, control, and recovery (

14,

15).

Given projections of the place of mental illness in the global burden of disease in the coming years (for example, depression alone is expected to rank third by 2020 [

16]), the unprecedented amount of resources being directed to science-based antistigma campaigns, and the frustration of clinicians, policy makers, and consumers in closing the need-treatment gap, it is crucial that the efficacy and implications of current efforts be evaluated. However, despite reported successes in launching campaigns and disseminating information, few studies have undertaken systematic evaluation of stigma reduction efforts (see references

17 and

18 for exceptions). The critical unanswered question is whether these efforts have changed public understanding and acceptance of persons with mental illness.

In this study, we assessed whether the cumulative impact of efforts over the past decade have produced change in expected directions. Using the mental health modules of nationally representative surveys 10 years apart, we examined whether the public changed during that interval in its embrace of neurobiological understandings of mental illness; its treatment endorsements for a variety of providers, including psychiatrists and general medical doctors; and its reports of community acceptance or rejection of persons described as meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, major depression, or alcohol dependence.

Method

Sample

The 2006 National Stigma Study-Replication reproduces the 1996 MacArthur Mental Health Study; both data collections were fielded as modules in the General Social Survey (GSS). The GSS is a biennial stratified multistage area probability sample survey of household clusters in the United States representing noninstitutionalized adults (age 18 and over). Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained interviewers using pencil and paper in the 1996 survey and a computer-assisted format in the 2006 survey. Mode effects were minimal and were unrelated to the data used here (

19). GSS response rates were 76.1% in 1996 and 71.2% in 2006.

The 1996 and 2006 GSS modules utilized a vignette strategy to collect data on public knowledge of and response to mental illness. This strategy helps circumvent social desirability bias and allows assessment of public recognition by providing a case description meeting psychiatric diagnostic criteria but no diagnostic label. Respondents were randomly assigned to a single vignette describing a psychiatric disorder meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia (N=650), major depression (N=676), or alcohol dependence (N=630). The gender, race (white, black, Hispanic), and education (<high school, high school, >high school) of vignette characters were randomly varied.

Because of the adoption in 2004 of a subsampling design to capture nonrespondents, weighting that adjusts for the selection of one adult per household is required for cross-year comparisons (sampling error=±3%). All analyses were conducted in Stata, release 11 (

20). Institutional review board approval for the GSS was obtained at the University of Chicago, as well as at Indiana University for secondary data analysis.

Measures

Respondents were read the randomly selected vignette, given a card with the vignette printed on it, and asked questions in three broad areas.

Attributions/causation.

Respondents were asked how likely it is that the person in the vignette is experiencing “a mental illness” and/or “the normal ups and downs of life,” as well as how likely the situation might be caused by “a genetic or inherited problem,” “a chemical imbalance in the brain,” “his or her own bad character,” and/or “the way he or she was raised.” Questions were not mutually exclusive, and respondents could endorse multiple attributions. Responses of “very likely” and “somewhat likely” were coded 1; “not very likely,” “not at all likely,” and “do not know” were coded 0. Analyses were run again with responses of “do not know” coded as missing as well as including controls for the vignette character's race, gender, and education, and substantively similar results were obtained (data available on request from the first author). A neurobiological conception measure was coded 1 if the respondent labeled the problem as mental illness and attributed cause to either a chemical imbalance or a genetic problem; it was coded 0 otherwise.

Treatment endorsement.

Respondents were asked whether the person in the vignette should seek consultation with or treatment by “a general medical doctor,” “a psychiatrist,” “a mental hospital,” and/or “prescription medications.” Responses were coded 1 if “yes” and 0 if “no” or “do not know.”

Public stigma.

Two sets of measures, for social distance and for perceptions of dangerousness, were used. The first asked respondents how willing they would be to have the person described in the vignette 1) work closely with them on a job; 2) live next door; 3) spend an evening socializing; 4) marry into the family; and 5) as a friend. Responses of “definitely unwilling” and “probably unwilling” were coded 1 (i.e., stigmatizing) and responses of “probably willing,” “definitely willing,” and “do not know” were coded 0. The second measure asked respondents how likely is it that the person in the vignette would “do something violent toward other people” and/or “do something violent toward him/herself.” Responses of “very likely” and “somewhat likely” were coded 1; responses of “not very likely,” “not at all likely,” and “do not know” were coded 0.

Covariates.

Respondents' age (in years), sex (coded 1 for female, 0 for male), education (coded 1 for at least a high school degree, and 0 otherwise), and race (code 1 for white, 0 for other) were included as controls. In 1996, the mean age of respondents was 43 years (SD=16); 51% were female, 31% completed more than a high school degree, and 81% were white. In 2006, the mean age was 45 years (SD=17); 54% were female, 39% completed more than a high school degree, and 75% were white. Profiles are consistent with Census Bureau data. Differences between samples refiect changes in the U.S. population (e.g., significant but small changes in education and race).

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated changes across years in public attributions, endorsement of treatment, and public stigma by comparing 1996 and 2006 unadjusted percentages. Because the data were weighted, a design-based F-statistic (

20) that utilized the second-order Rao and Scott (

21) correction was used to test the equality of the 1996 and 2006 percentages. To adjust for possible demographic shifts between survey years, we estimated logistic regression models for each outcome and for each vignette condition with controls for respondents' age, sex, education, and race. We then computed the difference in the predicted probabilities for a given outcome (e.g., mental illness) between 1996 and 2006 holding the control variables at their means for the combined sample; these are referred to as discrete change coefficients and are presented graphically. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were computed with the delta method and are shown graphically with tic marks.

We used logistic regression to examine the association of neurobiological conception with treatment endorsement and stigma. Models included controls for age, sex, education, and race and were run separately by year and vignette condition. Odds ratios are presented. To evaluate changes in the effect of neurobiological conception on treatment endorsement and stigma over time, discrete change coefficients were computed from logit models that included interactions between neurobiological conception and year and controls and year. Traditional tests of the equality of coefficients across groups (in this case the equality of the effect of neurobiological conception across survey year) cannot be used because the estimated logit coefficients confound the magnitude of the effect of a predictor with the degree of unobserved heterogeneity in the model (

22). Predicted probabilities are not affected by this issue of identification (J.S. Long, unpublished manuscript, 2009). Accordingly, we computed the discrete change in the predicted probability for a given outcome (e.g., treatment endorsement) between those who held a neurobiological conception and those who did not and then compared these discrete change coefficients across survey years. While these coefficients are not affected by the identification issue that makes it inappropriate to compare regression coefficients between times, the magnitude of the discrete change depends on the level at which the control variables are held. To control for differences in demographic variables between the survey years, we computed discrete change coefficients for each year with controls held at their means for the combined sample. To maintain metric consistency with the unadjusted percentages, predicted probabilities and discrete change coefficients were multiplied by 100 (e.g., 0.43 becomes 43%).

Results

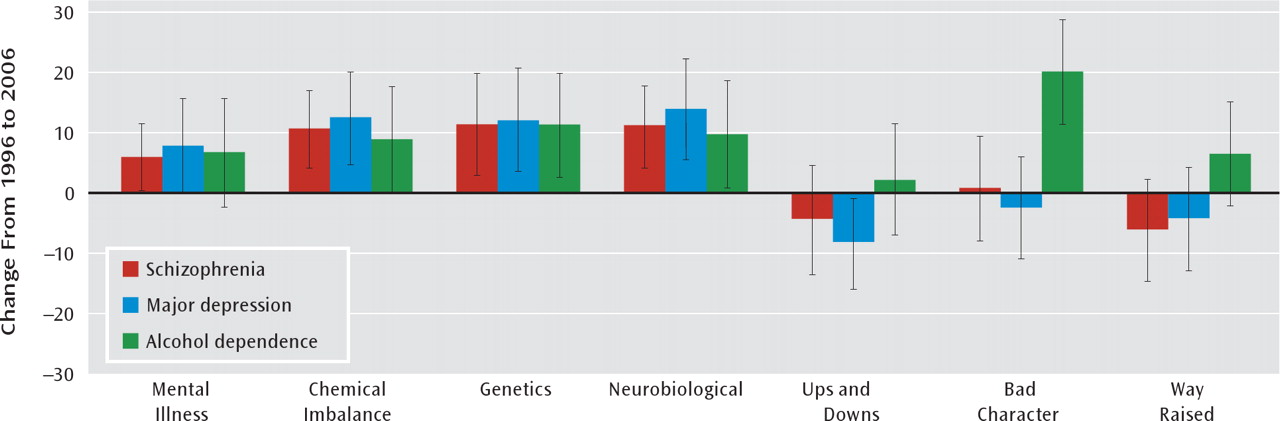

Attribution/Causation

More of the public embraced a neurobiological understanding of mental illness in 2006 than in 1996 (

Table 1). A large and statistically significant increase (6 to 13 percentage points) was evident across nearly all indicators and all vignette conditions. Neurobiological conception showed an increase of 10 percentage points for schizophrenia (from 76% to 86%; F=8.00, p=0.01), 13 points for depression (from 54% to 67%; F=9.94, p=0.002) and nine points for alcohol dependence (from 38% to 47%; F=4.06, p=0.04). Social or moral conceptions of mental illness decreased across most indicators, and a significant decrease in labeling the condition as “ups and downs” was observed for depression (from 78% to 67%; F=7.63, p=0.01). However, sociomoral conceptions of alcohol dependence were either largely unchanged or, for attributions of “bad character,” significantly increased (from 49% to 65%; F=13.50, p<0.001). Findings were largely unaffected by the addition of controls for respondents' age, sex, education, and race (

Figure 1). A slight attenuation of the year effect for chemical imbalance for alcohol dependence reduced the effect to nonsignificance. Further analyses (not reported) suggested that this was not due to the addition of any one covariate but to the addition of all covariates simultaneously.

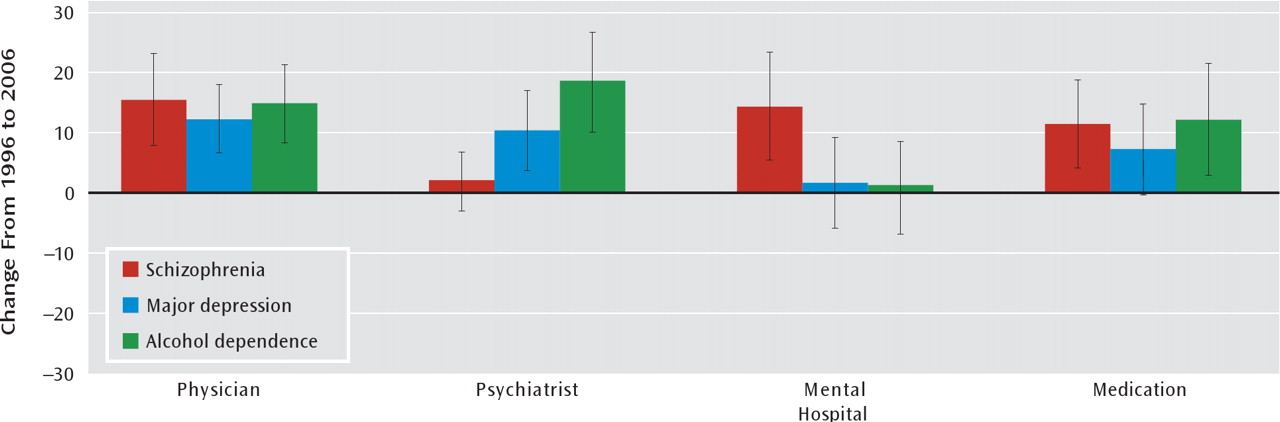

Treatment Endorsement

An across-the-board increase in public endorsement of medical treatment was reported (

Table 1). In 2006, a large majority supported both general and specialty care for individuals with mental illness. Over 85% indicated that the major depression vignette character should go to a psychiatrist (from 75% in 1996; F=9.27, p=0.002), and 79% recommended psychiatric treatment for alcohol dependence (from 61% in 1996; F=17.78, p<0.001). A significant increase in endorsement of prescription medicine was reported across all vignette conditions. Only treatment at a mental hospital remained unsupported by a majority of respondents for depression or alcohol dependence (27% and 26%, respectively). However, for schizophrenia, not only was hospitalization endorsed by a majority, but support for hospitalization significantly increased (from 53% to 66%; F=8.97, p=0.003). Findings were largely unaffected by the addition of controls for respondents' age, sex, education, and race (

Figure 2). The slight attenuation of the year effect in the endorsement of prescription medication for depression reduced the effect to nonsignificance.

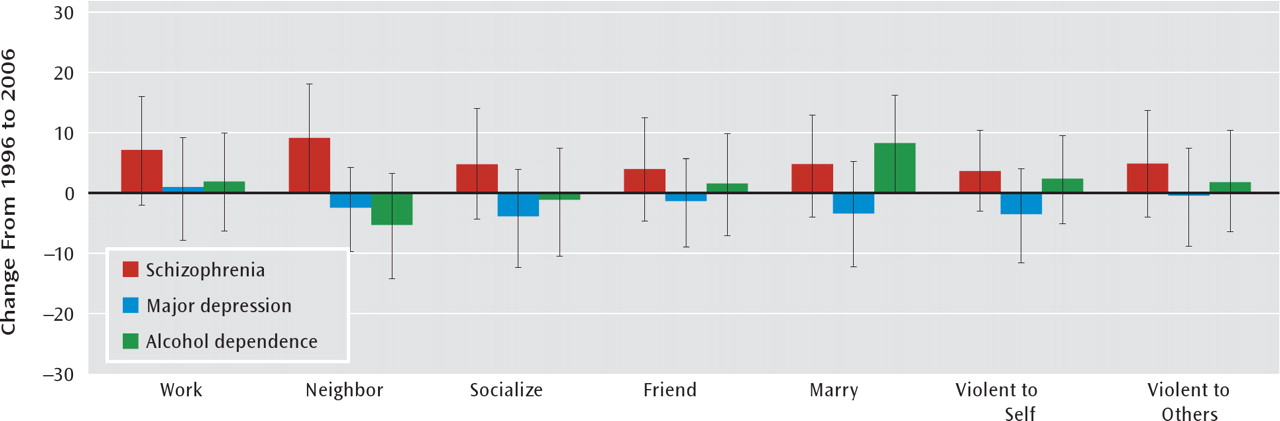

Public Stigma

No significant decrease was reported in any indicator of stigma, and levels remained high (

Table 1). A majority of the public continued to express an unwillingness to work closely with the person in the vignette (62% for schizophrenia, 74% for alcohol dependence), socialize with the person (52% for schizophrenia, 54% for alcohol dependence), or have the person marry into their family (69% for schizophrenia, 79% for alcohol dependence). In fact, significantly more respondents in the 2006 survey than the 1996 survey reported an unwillingness to have someone with schizophrenia as a neighbor (from 34% to 45%; F=6.31, p=0.01) or to have someone with alcohol dependence marry into their family (from 70% to 79%; F=4.01, p=0.05). Furthermore, a majority again reported that the vignette character with schizophrenia or alcohol dependence would likely be violent toward others. While stigmatizing reactions did not significantly decrease for the depression vignette, levels remained comparatively lower. Findings were unaffected by controls (

Figure 3).

Association of Neurobiological Conception With Treatment Endorsement and Stigma

In both survey years and across all conditions, holding a neurobiological conception of mental illness tended to increase the odds of endorsing treatment (e.g., for schizophrenia, from 1996 to 2006, the odds of endorsing a psychiatrist increased by a factor of 7.61; 95% CI=2.43–23.77, p<0.001; see

Table 2). However, in both years and across all conditions, holding a neurobiological conception of mental illness either was unrelated to stigma or increased the odds of a stigmatizing reaction. In 2006, holding a neuro-biological conception of schizophrenia increased the odds of preferring social distance at work by a factor of 2.20 (95% CI=1.02–4.76, p=0.05), and for depression it increased the odds of perceiving dangerousness to others by a factor of 2.70 (95% CI=1.53-4.78, p<0.001). In no instance was a neurobiological conception associated with significantly lower odds of stigma. Furthermore, for all but three indicators, the difference in the predicted probability between those who held a neurobiological conception and those who did not was larger in 2006 than 1996. For the depression vignette, a neurobiological attribution increased the predicted probability of perceived dangerousness to self by 20 points in 1996 and by 35 points in 2006, for a difference of 15 points (marginally significant, 95% CI=−1 to 31, p=0.07).

Discussion

Public attitudes matter. They fuel “the myth that mental illness is lifelong, hopeless, and deserving of revulsion” (

14, p. xiv). Public attitudes set the context in which individuals in the community respond to the onset of mental health problems, clinicians respond to individuals who come for treatment, and public policy is crafted. Attitudes can translate directly into fear or understanding, rejection or acceptance, delayed service use or early medical attention. Discrimination in treatment, low funding resources for mental health research, treatment, and practice, and limited rights of citizenship also arise from misinformation and stereotyping. Attitudes help shape legislative and scientific leaders' responses to issues such as parity, better treatment systems, and dedicated mental illness research funds (

23). Assumptions about these attitudes and beliefs have defined most messages of stigma reduction efforts (

14,

15).

With House Joint Resolution 174, the U.S. Congress designated the 1990s as the “Decade of the Brain,” premised on the assumption that the advancement of neuroscience was the key to continued progress on debilitating neural diseases and conditions, including mental illness. An explicit goal of the bipartisan measure was to enhance public awareness of the benefits to be derived from brain research. One of these benefits was to come in the area of stigma, and the Decade of the Brain “helped to reduce the stigma attached” to conditions, including “mind disorders” (

24). With a neurobiological understanding of mental illness, people would see that symptoms denote real illness and not volitionally driven deviant behaviors. As a consequence, people with mental disorders would be understood and treated rather than blamed and punished. This view found resonance in the Surgeon General's optimism for the stigma-reducing potential of neurobiological and molecular genetic discoveries (

15,

25). Similar optimistic statements have been common in medical journals (

26–28).

From a scientific perspective, claims that stigma was dissipating were optimistic and speculative, based on narrow, anecdotal, or unsystematic observation. Whether or not there has been a decrease in stigma is subject to empirical social science evaluation. Mental illness occurs in communities where “the public” is defined beyond political representatives, advocacy groups, and scientific organizations (

29).

Our analyses of data from the GSS, the premier, longest-running monitor of American public opinion, reveal that intensive efforts through the 1990s to 2006, mounted on the promise of neuroscience, have been rewarded with significant and widespread increases in public acceptance of neurobiological theories and public support for treatment, including psychiatry, but no reduction in public stigma. Furthermore, in surveys from both 1996 and 2006 and across all vignette conditions, holding a neurobio-logical conception of mental illness either was unrelated to stigma or tended to increase the odds of a stigmatizing reaction. Our most striking finding is that stigma among the American public appears to be surprisingly fixed, even in the face of anticipated advances in public knowledge.

The patterns reported here are bolstered by a growing body of similar international studies reporting mixed findings (

30–32). In a trend analysis in eastern Germany, Angermeyer and Matschinger (

30) documented an identical pattern of increases over time in public mental health literacy and the endorsement of neurobiological causation coupled with either no change or an increase in public stigma of mental illness. In Turkey (

33), Germany, Russia, and Mongolia (

34), the endorsement of neurobiological attributions was also associated with a desire for social distance, although it had no effect on social distance in Australia (

35) and in Austria (

36).

Our effort is not without limitations. First, vignette approaches can be sensitive to large and small changes in core descriptions (

10,

37). How the public would react to individuals at different places along the diagnostic spectrum remains unanswered. Our “cases” met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and simulated what individuals in the community encounter—a person with “problem” behaviors but no medical labels or history. This vignette strategy allowed us to explore the association of a neurobiological understanding of current or active “problem” behaviors with stigmatizing responses. However, the assumption underlying many antistigma interventions is that embracing a neurobiological understanding of mental illness will increase support for help-seeking behavior and subsequently lead to treatment that can mitigate symptoms. This in turn would reduce others' stigmatizing responses. Testing this idea of recovery and stigma reduction would require a different set of vignette circumstances than ours. It stands as an important hypothesis for future research. Second, attitudes are not behaviors, and predispositions may or may not closely track discrimination (

38). Both classic and recent studies suggest that attitudes reveal more negative tendencies than individuals are willing to act upon in real situations (

39,

40). While important, these limitations are unlikely to have affected our observed results.

Clinical, Research, and Policy Implications

What appears to have been mistaken is the assumption that global change in neuroscientific beliefs would translate into global reductions in stigma. Our analyses suggest that even if the embrace of neuroscience had been more pronounced, a significant and widespread reduction in stigma would not have followed. We are not the first to suggest that there may be unintended consequences or a backlash effect of genetic explanations of mental illness (

41). Even in 1999, the Surgeon General's report cautioned against a simplistic approach, noting that most recent studies suggested that increased knowledge among the public did not appear to translate into lower levels of stigma.

The critical question centers on future directions. As an alternative to our focus on neuroscience, we also considered another approach that pervades public debates. Given the efforts of the Treatment Advocacy Center to link violence in mental illness to policy changes necessary to improve the mental health system, we did a post hoc analysis that looked at the associations among public perceptions of dangerousness, social distance, and public support for increased funding. As Torrey (

42) has argued, people who recognize the potential dangerousness of untreated mental illness will support the infusion of more resources to the mental health system. Americans' assessments of dangerousness are high and, as in previous research, significantly related to social distance (

43). However, a measure of public support for federally funded services is not significantly associated with public perceptions of danger. Far from providing the public support needed to improve the mental health system, such fear only appears to have a detrimental effect on community acceptance.

We stand at a critical juncture. Neuroscientific advances are fundamentally transforming the landscape of mental illness and psychiatry. Given expectations surrounding the Decade of the Brain and the blame that pervaded earlier etiological theories of individual moral weakness and family deficits, it is hardly surprising that antistigma efforts relied on neuroscience. The “disease like any other” tagline has taken clinical and policy efforts far but is not without problems. It is our contention that future stigma reduction efforts need to be reconfigured or at least supplemented. An overreliance on the neurobiological causes of mental illness and substance use disorders is at best ineffective and at worst potentially stigmatizing.

Historians, looking to instances in the past where stigma decreased, suggest that continued advances in neuroscience that will prevent, cure, or control mental illnesses are critical to developing treatments that will render them less disabling (

44). In fact, the past decade has witnessed major policy and clinical progress, including the passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in 2008 and inroads into the genetics of schizophrenia (

45). However, clinicians need to be aware that focusing on genetics or brain dysfunction in order to decrease feelings of blame in the clinical encounter may have the unintended effect of increasing client and family feelings of hopelessness and permanence.

Antistigma campaigns will require new visions, new directions for change, and a rethinking of what motivates stigma and what may reduce it, a conclusion reached at a 2009 meeting of stigma experts at the Carter Center. While new research will be needed, current stigma research suggests that a focus on the abilities, competencies, and community integration of persons with mental illness and substance use disorders may offer a promising direction to address public stigma (

46).