Death from accidental overdose—unintentional death resulting from poisoning by illegal drugs, alcohol, or medications—is the second most common cause of accidental death in the United States (

1). The rate of fatal unintentional overdose or poisoning among adults over age 18 increased by 124% between 1999 and 2007 (

1). This increase is attributed largely to prescription drug overdoses, and particularly to overdoses related to opioid pain medication (

2,

3). Given the importance of health systems to the distribution of prescription drugs that carry overdose potential and the treatment of individuals at risk for overdose, it is crucial to identify at-risk groups in clinical populations for targeted interventions.

Little research has been conducted on risk factors for fatal accidental overdose, in clinical or other settings. Much of the available data come from surveillance systems (such as those implemented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]), which have limited data on the characteristics of individuals who died from overdose. Previous analyses of these data indicate that men are more likely to die by accidental overdose, and individuals ages 40 to 49 have the highest rates of accidental overdose (

4). Analyses of overdose decedents in West Virginia suggest that substance abuse and mental illness may be common among those who die of an overdose (

5,

6), although the lack of a comparison group did not allow the determination of whether the prevalences of these characteristics are significantly elevated.

More detailed information regarding risk for nonfatal overdose has come from survey-based studies of chronic users of illegal drugs. These studies typically have samples from treatment settings and are often limited to one geographical region. Analyses suggest that individuals who meet criteria for substance use disorders (

7–

10) and individuals experiencing psychological distress (

10,

11) have an elevated risk of nonfatal accidental overdoses compared with individuals without these conditions.

Although understanding risk factors for accidental overdose among chronic drug users is important, questions regarding risk for accidental overdose in broader clinical populations remain unanswered. The purpose of this study was to examine the risk of accidental overdose associated with substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among the entire population of patients who used Veterans Health Administration services within a single year. We examined clinical and mortality data to assess possible associations between specific psychiatric diagnoses and patients' risks of accidental overdose death over a 7-year observation period. Because individuals with psychiatric conditions are more likely to have substance use disorders as well, we also examined the degree to which associations between psychiatric disorders and accidental overdose risk may be accounted for by comorbid substance use disorders. Additionally, we examined the association of psychiatric disorders with medication-related and alcohol- or illegal drug-related overdoses separately because of the different clinical implications for these two outcomes.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive information for the study population. The patient population of the Veterans Health Administration in fiscal year 1999 was largely male (90.0%), and 75.4% were between ages 40 and 59. Substance use disorders and depressive disorders were the most common types of disorders in this population in fiscal year 1999 (10.0% and 14.5%, respectively).

Between fiscal years 2000 and 2006, 4,485 members of the cohort died of an accidental overdose. Unadjusted analyses of the association of accidental overdose death with demographic characteristics and psychiatric disorders are reported in

Table 1. The risk of accidental overdose was higher among men than women and higher among individuals between the ages of 30 and 59 than both those younger than 30 and those older than 59. All examined psychiatric disorders had a statistically significant unadjusted association with accidental overdose death, with hazard ratios ranging from 3.41 (for non-major depressive disorder depression) to 21.95 (for opioid use disorders). The estimated unadjusted hazard ratio was higher for substance use disorders than for other disorders.

Table 2 reports Cox proportional hazards modeling of the risk of accidental overdose mortality in the study population, adjusted for demographic and nonpsychiatric clinical characteristics. All diagnoses were significantly associated with accidental overdose death (all p values <0.001) after adjustment. However, effect sizes were attenuated after adjustment, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.82 (95% CI=1.66–1.99) for schizophrenia to 8.78 (95% CI=7.73–9.96) for opioid use disorders. Among specific drug use disorders, the risk of accidental overdose was markedly higher for individuals with opioid use disorders than for those with other specific drug use disorders (hazard ratios ranged from 2.86 to 5.16).

Table 2 also reports the association of each disorder with medication-related overdose death and alcohol/illegal drug-related overdose death specifically. Of the 4,485 accidental overdose deaths, 1,448 were alcohol/illegal-drug related, and 3,390 were medication-related, with 701 cases that were both alcohol/illegal drug-related and medication-related. Substance-specific data were not available for 348 cases. Comparing the two sets of models, we found that the association of depressive disorders and non-PTSD anxiety disorders was stronger with medication-related overdoses than with alcohol/illegal drug-related overdoses. In contrast, drug use disorders (and particularly cannabis and stimulant use disorders) had stronger associations with alcohol/illegal drug-related overdoses than with medication-related overdoses.

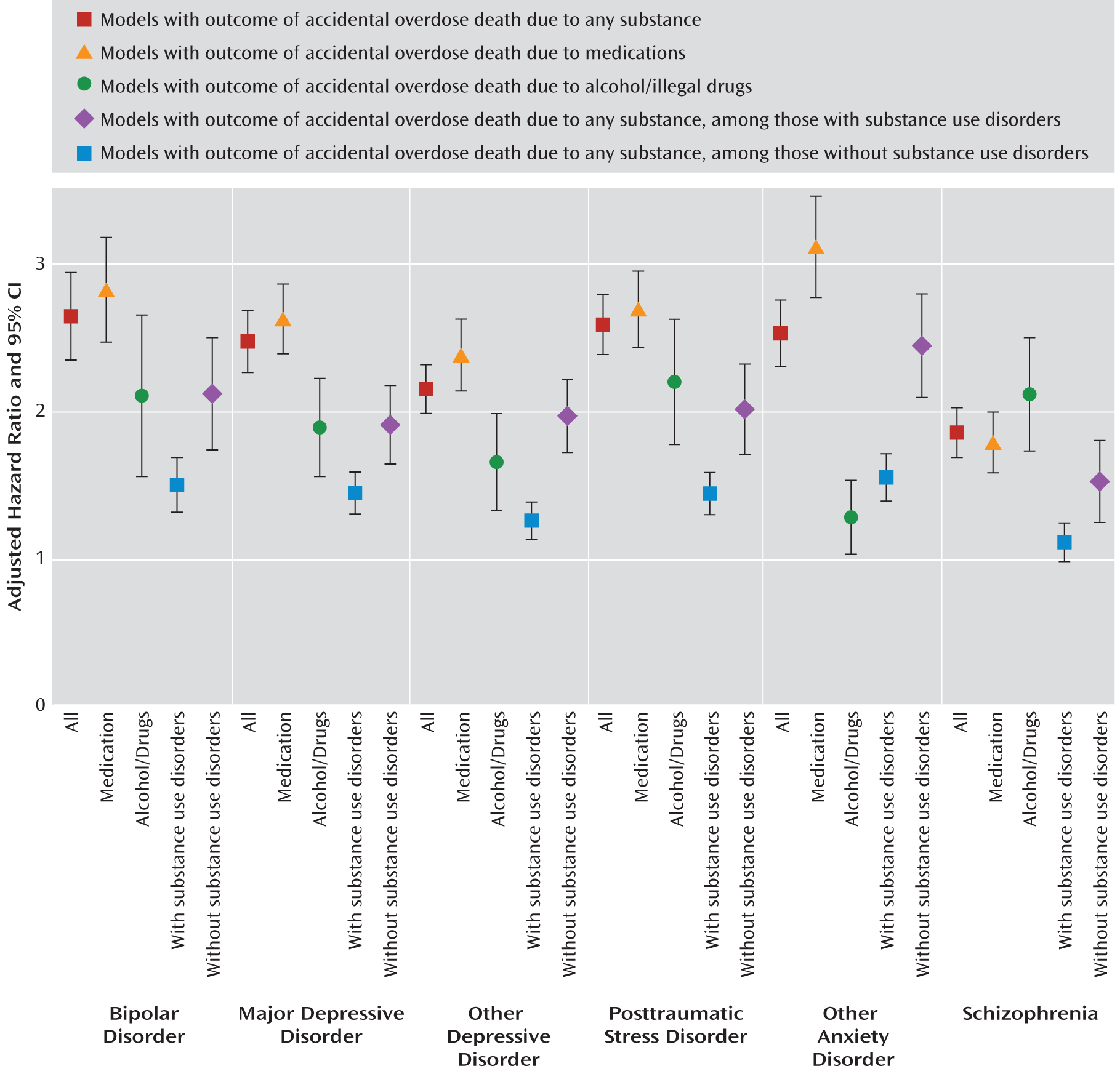

After additional adjustment for substance use disorder status, all other psychiatric diagnoses continued to have a statistically significant association with accidental overdose death (all p values <0.001), with hazard ratios ranging from 1.16 to 1.79 (series 1 in

Table 3). Among those with a substance use disorder, the association of other psychiatric disorders with accidental overdose death was significant for all disorders except schizophrenia, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.24 to 1.53 (series 2 in

Table 3). Among those without a substance use disorder, all other psychiatric disorders were significantly (all p values <0.001) associated with risk of accidental overdose death, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.47 to 2.39 (series 3 in

Table 3). For each non-substance use disorder psychiatric diagnosis, the 95% CIs of the estimated hazard ratio of the association with accidental overdose did not overlap between the series 2 and series 3 models in

Table 3, suggesting that the association of these disorders was stronger for those without substance use disorders than for those with substance use disorders. Models testing the interaction of substance use disorder status with each of the other psychiatric disorders confirmed this finding (beta values of interaction terms from –0.3 to –0.5). We also examined the association of having a substance use disorder among those individuals with each non-substance use disorder diagnosis in a separate model, adjusting for the same set of covariates (results not shown). Across models, the estimated hazard ratio of the association of substance use disorder with accidental overdose mortality ranged from 3.06 to 3.53 (all p values <0.001).

All adjusted models of non-substance use disorder psychiatric diagnoses are presented together in

Figure 1.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively characterize the longitudinal relationship between psychiatric disorders and death from accidental overdose in an adult clinical population. Data from this national cohort of all patients seen in the VA health system within a single year indicate that both substance use disorders and psychiatric diagnoses were consistently associated with an elevated risk of death from accidental overdose. Substance use disorders, particularly opioid use disorders, represented the strongest risk factor for overdose, yet other psychiatric disorders also increased risk of death from overdose.

Effect sizes for all psychiatric disorders were smaller and fairly similar across disorders after adjusting for substance use disorders. However, even in analyses adjusting for comorbid substance use disorders, psychiatric disorders were associated with hazard ratios ranging from 1.2 to 1.8, suggesting that comorbid substance use disorders partially, but not entirely, account for the observed association between psychiatric disorders and accidental death from overdose. These findings suggest that accidental overdose is not just an adverse outcome of substance use but may also result from psychopathology. The consistent positive relationship between psychiatric disorders and accidental overdose suggests that psychological symptoms and problems may play a role in death due to accidental overdose that is similar to the role they play in suicide. Increases in negative mood and hopelessness may result in greater risk taking in terms of use and abuse of drugs, alcohol, and medications. In some cases, the accidental or unintentional overdose may not be a suicide attempt per se but the result of an indifference toward death (

20), in contrast with a desire to die, as in the case of many suicide deaths.

Another possible explanation for our findings is that these accidental overdoses observed among patients with psychiatric disorders were simply misclassified suicides. However, the association of age in this study of accidental overdose deaths, with the highest risk of death experienced by persons 30–49 years of age and a steep decline in risk after age 49, was in sharp contrast to the age effect for suicide previously reported in the same population (

12), with fairly stable risk of suicide across all ages greater than 30. This would be inconsistent with misclassification if it was due to random error. Moreover, a study using classification and regression tree methods (

21) suggests that misclassification of suicide as unintentional overdose is uncommon.

In addition to a direct cause-and-effect relationship, there are several other possible explanations for the relation of psychiatric diagnoses with accidental overdose mortality. Medications indicated for use in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses likely increase the risk for overdose, particularly when combined with alcohol, illegal drugs, and nonpsychiatric medications. This may be particularly true of antianxiety and antidepressant medications (

6,

22,

23). The finding that depressive disorders and non-PTSD anxiety disorders had stronger associations with medication-related overdoses than with alcohol/illegal drug-related overdoses provides some support for the salience of medications in the risk of accidental overdose for individuals with these psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, patients with higher levels of psychic distress may be inclined to take more of their medications than prescribed in an effort to reduce distress, which could lead to an increased risk of accidental overdose. Medications may also cause confusion, which in turn could lead to overconsumption of medications when previous medication intake is forgotten. More research is needed to better understand the role of specific prescribing patterns of psychoactive medications in accidental overdose risk.

Another possible explanation is that individuals with psychiatric diagnoses are also more likely to engage in heavy drinking and illegal drug use than individuals without psychiatric diagnoses (

24), and some of this variation is likely not captured by substance use diagnoses in the medical record. The stronger associations between each psychiatric disorder and accidental overdose death among those without substance use disorders than among those with substance use disorders may also be due to the fact that the reference groups among those without substance use disorders are less likely to have additional comorbid psychiatric disorders. Other potential mediating factors that could explain the association between psychiatric disorders and overdose include homelessness and incarceration, which are both more common among those with mental illnesses (

24,

25) and have been found to be associated with nonfatal overdose risk among substance users (

26,

27).

There are several notable limitations to this study. The data are from clinical data in administrative records rather than from interviews with participants, and consequently the rates of undiagnosed psychiatric disorders are unknown. However, clinical diagnoses made in real-world settings may be quite germane when identifying subgroups of patients who may benefit from clinician interventions to reduce risks. The observed relationships may also be an underestimate because diagnoses that were not recorded until after fiscal years 1998 and 1999 were not included. The large sample size resulted in well-powered analyses but may also have resulted in an increase in the risk of type I errors.

This was a study of patients treated by the Veterans Health Administration, and findings may not be generalizable to other health care populations. However, the Veterans Health Administration constitutes one of the largest health systems in the country, and health systems have the opportunity to engage in prevention and intervention strategies to reduce overdose risk in their treatment populations. Indeed, because the recent increase in accidental overdose deaths appears to be related to medication-related poisonings specifically (

3), and given recent findings indicating that prescribing patterns may be directly related to overdose risk (

28,

29), health systems are particularly relevant to the study of overdose mortality.

Our findings suggest the importance of risk assessment and overdose prevention by mental health providers for patients who have a number of psychiatric conditions. Although patients with substance use disorders (and particularly opioid use disorders) should be a primary target of interventions given the high level of risk associated with these diagnoses, patients with other psychiatric diagnoses also have an elevated risk. Patients with several predisposing diagnoses may particularly benefit from more intensive clinical management, especially those who are being treated with opioids, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and other medications that are toxic in overdose. A number of accidental overdose prevention interventions targeting substance users have been developed with promising results, but these studies have often focused on heroin users (

30–

33). More research is needed to elucidate effective interventions to reduce risk of death from accidental overdose for patients misusing other substances and for patients who have concurrent psychiatric disorders. Our findings also suggest that mental health providers need to assess and address the risk of death from accidental overdose among patients with psychiatric disorders in addition to risk for suicide. The development of evidence-based interventions to reduce accidental overdose among these vulnerable patients is sorely needed.