Melancholic, anxious, and atypical symptom features have been used to designate subtypes that could address the heterogeneity among depressed patients and help in selecting from among the different treatment options (

9). Data on the clinical utility of these subtypes in treatment selection—that is, whether particular subtypes show different patterns of symptom reduction with any given treatment—are inconsistent. For example, some findings suggest that patients with the melancholic subtype have a significantly less robust response to antidepressant medications than do patients with non-melancholic depression (

10), while other findings indicate no differences (

11) or higher remission rates among patients with melancholic depression on some outcomes and no differences on others (

12). In the initial phase of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, patients with melancholic depression were less likely to remit compared with those with other subtypes when treated with open-label citalopram, but these differences were no longer evident after adjustment for baseline differences (

13). A similarly mixed picture has emerged for atypical features. Some findings suggest that patients with atypical depression have lower remission rates than patients without atypical features (

14), while other findings indicate no differences (

10) or that lower remission rates were no longer significant after adjustment for pretreatment baseline differences (

15). In the STAR*D study, participants with anxious depression had significantly lower remission rates across treatment steps (

16), but a study by Uher et al. (

10) found no difference between anxious and nonanxious patients with depression on two of three outcome measures. Russell et al. (

17) reported significantly better response and remission rates among chronic depression patients who were highly anxious compared with those without significant anxiety.

Findings are also mixed on whether symptom-based subtypes are useful in the selection of antidepressant medications. Patients with melancholic depression have been found to be more responsive to tricyclic antidepressants than to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in some studies (

18,

19) but not in others (

10). The evidence is mixed on whether SSRIs are more effective than tricyclics among patients with atypical depression (

10,

20,

21). Fewer studies have reported on whether patients with anxious depression respond preferentially to one medication over others, but Russell et al. (

17) found no differences in response to an SSRI versus imipramine, and Uher et al. (

10) found that patients with anxious depression responded similarly to escitalopram and nortriptyline.

The current literature suffers from additional limitations. First, the three symptom-based subtypes (

9) were developed independently and are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Thus, patients characterized as having atypical depression may also meet criteria for anxious or melancholic depression. Failure to account for overlap carries a risk of misclassification and may compromise efforts to determine whether meeting criteria for a specific subtype should inform clinical decision making. Second, many studies examine one subtype at a time using binary classifications (

11,

12,

15), which precludes the examination of whether one subtype may be more useful than another in predicting outcome. Third, to our knowledge, no studies have reported on whether patients who do not meet criteria for any of the subtypes respond differently than do those who meet criteria for one or more subtypes.

In this exploratory study, we examined the first half of a projected sample of 2,016 patients with depression who were participants in the International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression (iSPOT-D) (

22). Our study had two specific aims: 1) to describe the proportions of individuals who met criteria for melancholic, anxious, and atypical depression subtypes, the proportions in which each combination of subtypes overlapped in individual patients, and the proportion in which criteria for any of these subtypes were not met; and 2) to evaluate whether subtype profile predicted general or differential responsiveness to commonly used antidepressants. We hypothesized that 1) among participants who met criteria for a single subtype, melancholic subtype status would be a general predictor of lower remission rate compared with atypical or anxious subtype status (

10,

14); 2) the presence of more than one subtype would be a general predictor of a lower remission rate than would be observed among patients with just one subtype; 3) patients who did not meet criteria for any subtype would a have higher remission rate than those who met criteria for a single subtype. No hypotheses were made regarding moderation of treatment effects; analyses related to that question were exploratory. In order to gauge the generalizability of our findings on both subtype distribution and antidepressant outcome, we descriptively compared our results with those derived from an additional analysis of participants in step 1 of the STAR*D trial (

5).

Discussion

This study revealed two main findings. First, there was substantial overlap among the three subtypes of major depressive disorder in both the iSPOT-D and STAR*D samples, indicating that the subtypes are not “pure.” Second, subtype status in the iSPOT-D sample did not predict antidepressant outcome overall or differentially, whether assessed categorically or continuously; results were similar for the STAR*D sample.

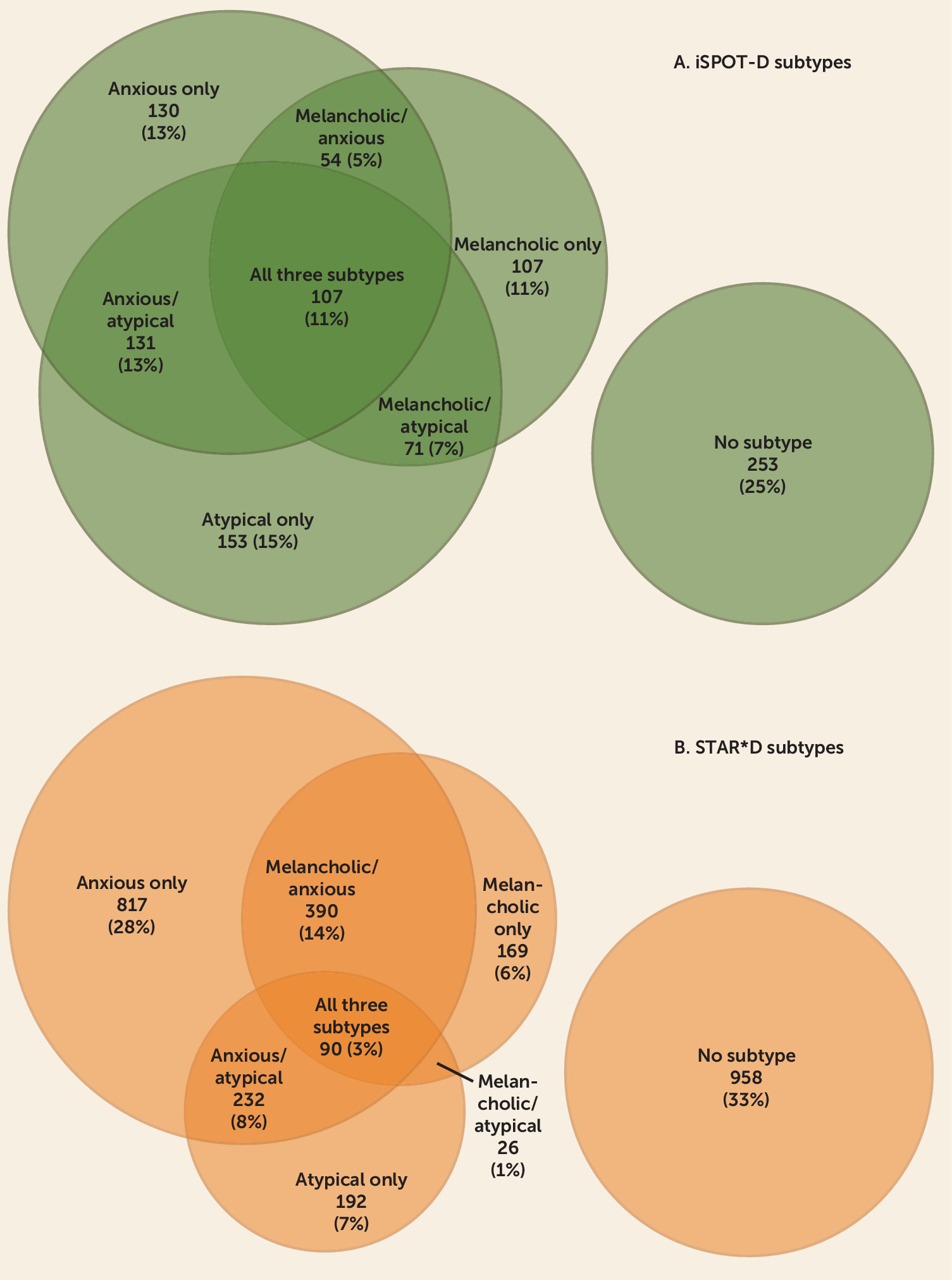

Specifically, in terms of subtype overlap, 25% of the iSPOT-D participants did not meet criteria for any subtype, 39% exhibited a pure-form single subtype, and 36% met criteria for more than one subtype. Among STAR*D participants, 33% did not meet criteria for any subtype, 41% met criteria for a single subtype, and 26% met criteria for more than one subtype. Put differently, among those who met criteria for a subtype, 48% and 39% in the iSPOT-D and STAR*D studies, respectively, met criteria for more than one subtype.

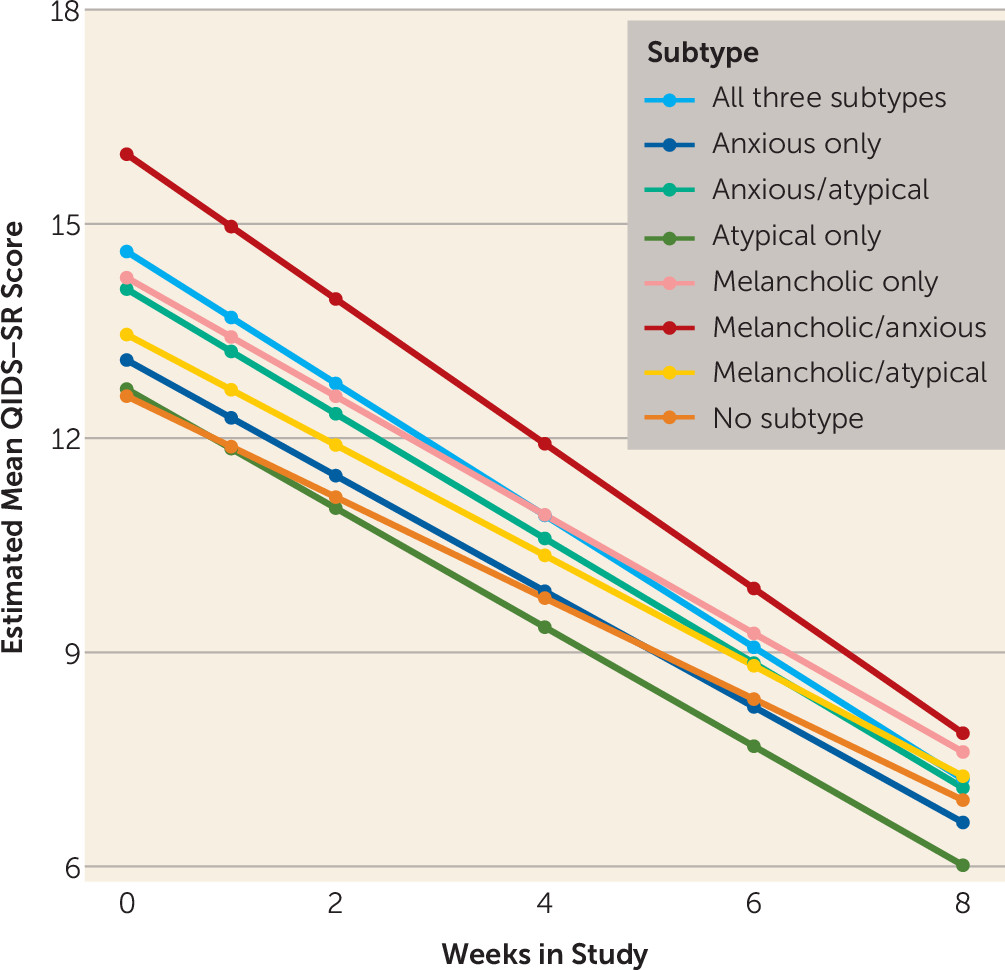

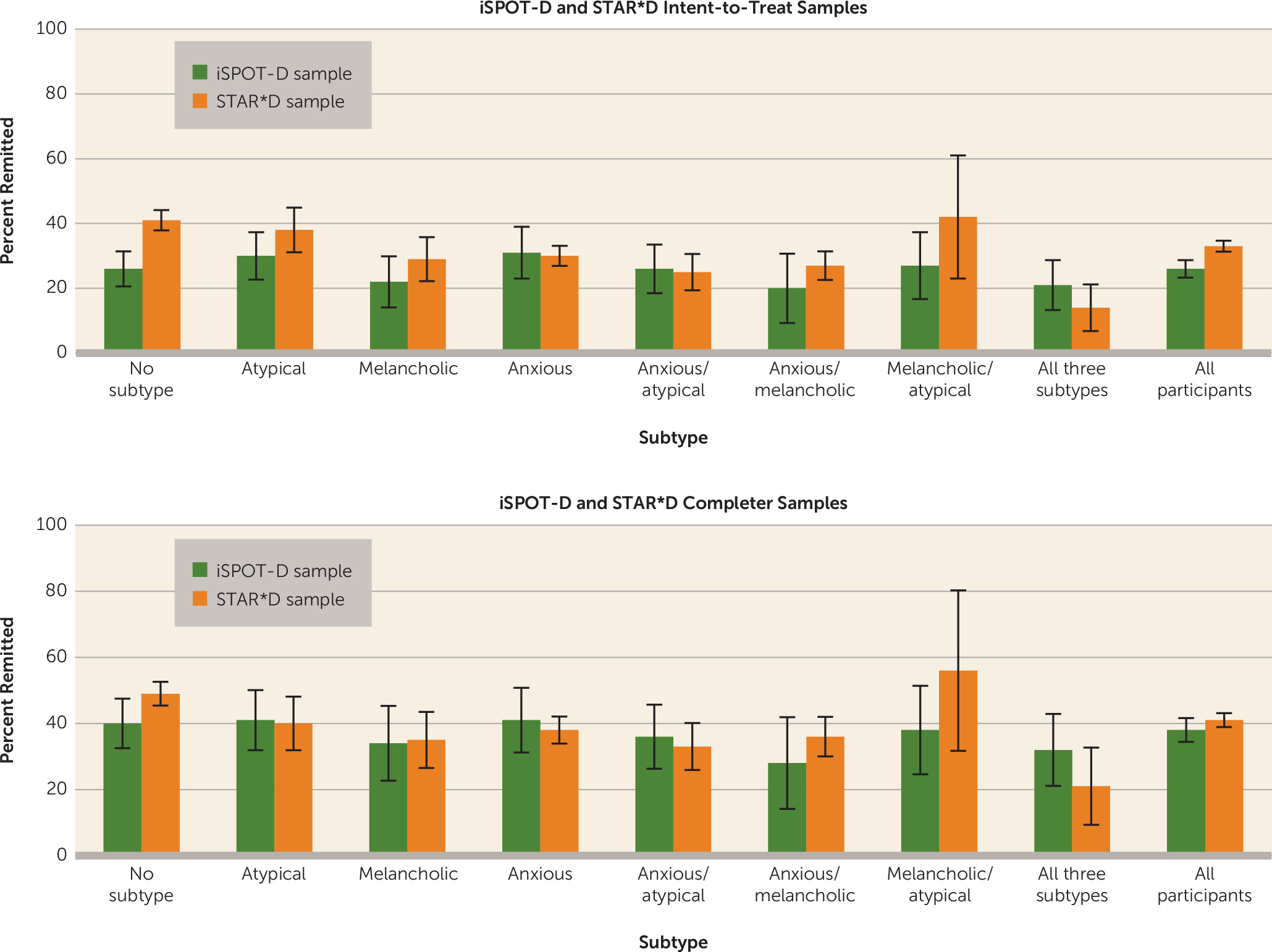

In terms of outcomes, after adjustment for age, gender, and baseline severity, remission rates and symptom reduction in the iSPOT-D sample did not differ among the pure melancholic, anxious, and atypical subtypes, nor did remission rates or change from baseline in depression symptom score differ among participants who met criteria for one, more than one, or no subtype. The slope of change was flatter among those who met criteria for no subtype and differed from the other groups because of the lower mean baseline score in this group. This group’s outcome at trial completion was similar to the outcomes of the other subgroups. These results were partially but not fully consistent with those from the STAR*D data set. Although the two trials had considerably different sampling frames, recruitment and eligibility criteria, comorbidities, and medications and dosages, remission rates in the two studies did not differ among the three pure subtypes in either the intent-to-treat or the completer analysis. Remission rates (and their 95% confidence intervals) were similar among the mixed subtypes as well. The only difference in remission rates was observed in the no-subtype groups, where the intent-to-treat STAR*D rates were higher than the iSPOT-D rates.

Our finding that remission rates and symptom reduction were similar in the melancholic, atypical, and anxious subgroups diverges from several other reports. Uher et al. (

10), who included an anxious-somatizing group as well as the three subgroups that we examined here, found that the melancholic subgroup had lower symptom reduction than the other groups, although the difference was judged not to be clinically significant. The Uher et al. study involved a different drug regimen (escitalopram or nortriptyline) and longer treatment duration (12 weeks). Gili et al. (

14), in a naturalistic investigation of depressed patients in which clinicians were free to prescribe medications as they saw fit, found that patients with melancholic depression had lower rates of remission than those without melancholic depression, and that patients with atypical depression had lower remission rates than those without atypical depression. However, in addition to differences in the medications prescribed, baseline symptom values were not collected in that study, and it is unclear whether the same results would have been obtained with baseline severity as a covariate, as was done in our study. Yang et al. (

12) found that patients with melancholic depression did not differ significantly from those with non-melancholic depression on remission or response as assessed by the HAM-D but had a higher remission rate as assessed by the Clinical Global Impressions Scale. However, in addition to differences between that study and ours in the medications prescribed and the length of the study period (12 weeks compared with 8 weeks), Yang et al. did not statistically adjust for the influence of baseline depression severity.

Our findings on melancholic depression are consistent with those of McGrath et al. (

13) in the open-label phase of the STAR*D trial, Rush et al. (

32) in step 2 of the STAR*D trial, and Bobo et al. (

11) in the Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes study. Our finding of no significant difference in outcome between the atypical subtype group and the other subtype groups is consistent with the findings of Stewart et al. (

15), who reported no differences between participants with and without atypical depression after adjusting for baseline variables in the open-label phase of the STAR*D trial, and with the findings of Uher et al. (

10), who also found no differences in outcome between participants with atypical and non-atypical depression.

In the iSPOT-D sample, we found no difference in outcome between any of the anxious subtypes and the other groups, which is not consistent with Fava et al. (

16), who found anxious depression to have lower remission rates than nonanxious depression in both steps 1 and 2 of the STAR*D trial. However, the STAR*D authors compared all patients who met criteria for anxious depression (53% in step 1) to all nonanxious patients. As our findings reveal, a large proportion of those who met criteria for anxious depression in step 1 of the STAR*D trial also met criteria for other subtypes, with only 28% meeting criteria for the pure anxious subtype.

The statistical approach we employed to examine the relationship between depressive subtype and antidepressant outcome is different from those used in previous studies, which typically have compared one subgroup to all other members of a sample. Our analysis compared each of the eight subgroups to every other subgroup individually rather than to the sample as a whole. Our findings suggest that comparing one subtype to all other members of a sample in a two-group comparison will inevitably involve misclassification, as some participants in the reference subtype group will also meet criteria for other subtypes. Furthermore, studies that compare one subtype to all others in a large sample (

14,

16) are likely to be sufficiently powered to find differences that may be statistically significant but may or may not be clinically significant (

10).

We found no evidence that any subtype, whether mixed or “pure,” moderated outcome with the three medications used in this trial. The medications in iSPOT-D were chosen based on their frequency of use as well as their approval in five countries (

22). Because tricyclic antidepressants were not included as a study medication, we were unable to confirm or disconfirm whether patients with melancholic depression respond preferentially to tricyclics (

18,

19) or whether patients with atypical depression respond preferentially to SSRIs compared with tricyclics (

20,

21). Still, our findings are consistent with those reported in step 2 of the STAR*D trial, in which atypical, anxious, and melancholic features did not predict response to one antidepressant medication versus another (

32).

Among the strengths of this study were that we utilized a large sample from an effectiveness trial (iSPOT-D), with broad inclusion and exclusion criteria enhancing the external validity of the study’s findings. The sample size was adequate for subtype classification estimations and for the formal testing of a priori hypotheses with full statistical power.

The iSPOT-D study had several limitations. First, although antidepressant dosages were similar between subtypes, they were at the lower end of the recommended ranges. It is unknown whether higher dosages might have been associated with better response in one or two of the subtypes, revealing a different pattern of remission or symptom reduction than was observed in our investigation. Moreover, it could be argued that the dosage of extended-release venlafaxine (83 mg/day) in iSPOT-D is sufficient only to test its serotonin reuptake inhibitor properties but not its efficacy as a dual-action agent and that the findings in this report cannot be generalized to medications with different mechanisms of action. Second, the length of treatment in iSPOT-D was 8 weeks, and it is possible that a different pattern of findings would have emerged over a longer course of treatment. In the longer-duration STAR*D trial, trajectories of symptom reduction indicated that about two-thirds of patients who achieved remission did so within the first 8 weeks of treatment (

5). Third, not all depression subtypes were examined (e.g., we did not include psychotic depression). Fourth, our findings pertain specifically to the relationship between categorical subtypes and antidepressant treatment outcome. It is possible, for example, that dimensional assessments of anxious, atypical, or melancholic symptoms correlate directly with amount of symptom change.