Huntington’s disease is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disease that typically manifests in adulthood with motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms. The disease occurs as a result of an expanded number of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats in the protein-coding DNA sequence of the

Huntingtin gene on chromosome 4. A formal diagnosis of Huntington’s disease is usually given based on the presence of significant motor symptoms, including chorea, rigidity, and bradykinesia. Huntington’s disease is progressive over several years, leading to functional decline and premature death (

1,

2). Cognitive changes include progressive deficits in learning, executive and sensory functions, and attention, resulting in dementia (

3–

6). Psychiatric manifestations in Huntington’s disease include depression, irritability, apathy, perseverations, obsessions, and occasionally psychosis (

7–

14). With a few exceptions (

7,

15), psychiatric changes are not typically related to indices of progression.

The neurodegeneration of striatal and cortical structures underlying the symptomatic presentation of Huntington’s disease has been known for some time, and while there is an association between the number of CAG repeats and age at onset, there is significant unexplained variability in the presentation and severity of symptoms, in particular their psychiatric manifestations. The ability to test for the Huntington’s disease mutation prior to onset of symptoms, known as the illness prodrome, has provided the opportunity to study the development of disease manifestations over time. The longitudinal Neurobiological Predictors of Huntington’s Disease study (PREDICT-HD) has identified motor, cognitive, psychiatric, and brain imaging changes that occur in individuals with the mutation (

16–

19). We previously reported an increase in psychiatric syndromes for individuals in the prodrome of Huntington’s disease at the time of study entry, and we have shown increases in number and severity of symptoms cross-sectionally as estimated proximity to motor diagnosis increases (

4,

19–

21).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest published longitudinal study of psychiatric manifestations in prodromal Huntington’s disease. Some previous research has suggested that severity of psychiatric and/or behavioral manifestations of Huntington’s disease is not associated with progression of the disease (

2,

30). Contrary to this popularly held belief, however, 19 of 24 measures examined showed cross-sectional and longitudinal differences between participants with prodromal Huntington’s disease and gene-mutation-negative controls. Of the remaining five measures analyzed, three also showed elevated baseline scores, although change over time did not differ. Although previous research has consistently emphasized the clinical importance of the psychiatric symptoms associated with Huntington’s disease, and a wealth of studies have noted the higher prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and increased psychiatric distress in Huntington’s disease, few studies have documented longitudinal progression of the psychiatric disturbances in Huntington’s disease. These findings are consistent with the report of Craufurd et al. (

7), which provided longitudinal data for 111 persons with a diagnosis of Huntington’s disease and found that all three subscales of the Problem Behaviors Assessment for Huntington’s Disease showed significant change over time. Furthermore, Craufurd et al. showed that although all three psychiatric subscales (apathy, irritability, depression) worsened over time in the earliest stages of Huntington’s disease (stages I and II), only apathy continued to progress with disease progression into stages II–IV. Comparisons with other research in prodromal Huntington’s disease, however, are more central to the present findings. Kirkwood et al. (

31) followed 45 prodromal gene mutation carriers and reported a greater increase in psychiatric abnormalities over an interval of 3.7 years. The greatest changes were noted in irritability and hostility. More recently, Tabrizi et al. (

32) followed 120 prodromal Huntington’s disease gene mutation carriers and reported worsening apathy over 36 months. The present study replicates and extends these findings and provides confidence that the psychiatric symptoms seen in Huntington’s disease progress with disease severity and thus are likely secondary to the neurodegenerative disease process.

The detection of neurodegenerative diseases has progressed considerably, as reflected in DSM-5, which describes the emergence of mild cognitive impairment as a precursor, or prodromal stage, evident in progressive brain disease. Mild cognitive impairment in Huntington’s disease has been documented in at least 40% of persons carrying the gene mutation (

33,

34), and numerous studies have demonstrated that cognitive decline can be detected a decade before onset of motor symptoms (

35). Given the plethora of publications demonstrating early cognitive decline in Huntington’s disease, in concert with the findings of the present study showing psychiatric symptom progression prior to onset of motor symptoms, the monosymptomatic diagnostic criteria seem out of date. Since mental health professionals may see prodromal Huntington’s disease in clinical practice a decade before movement disorder specialists do, an earlier diagnosis may be prudent for many individuals.

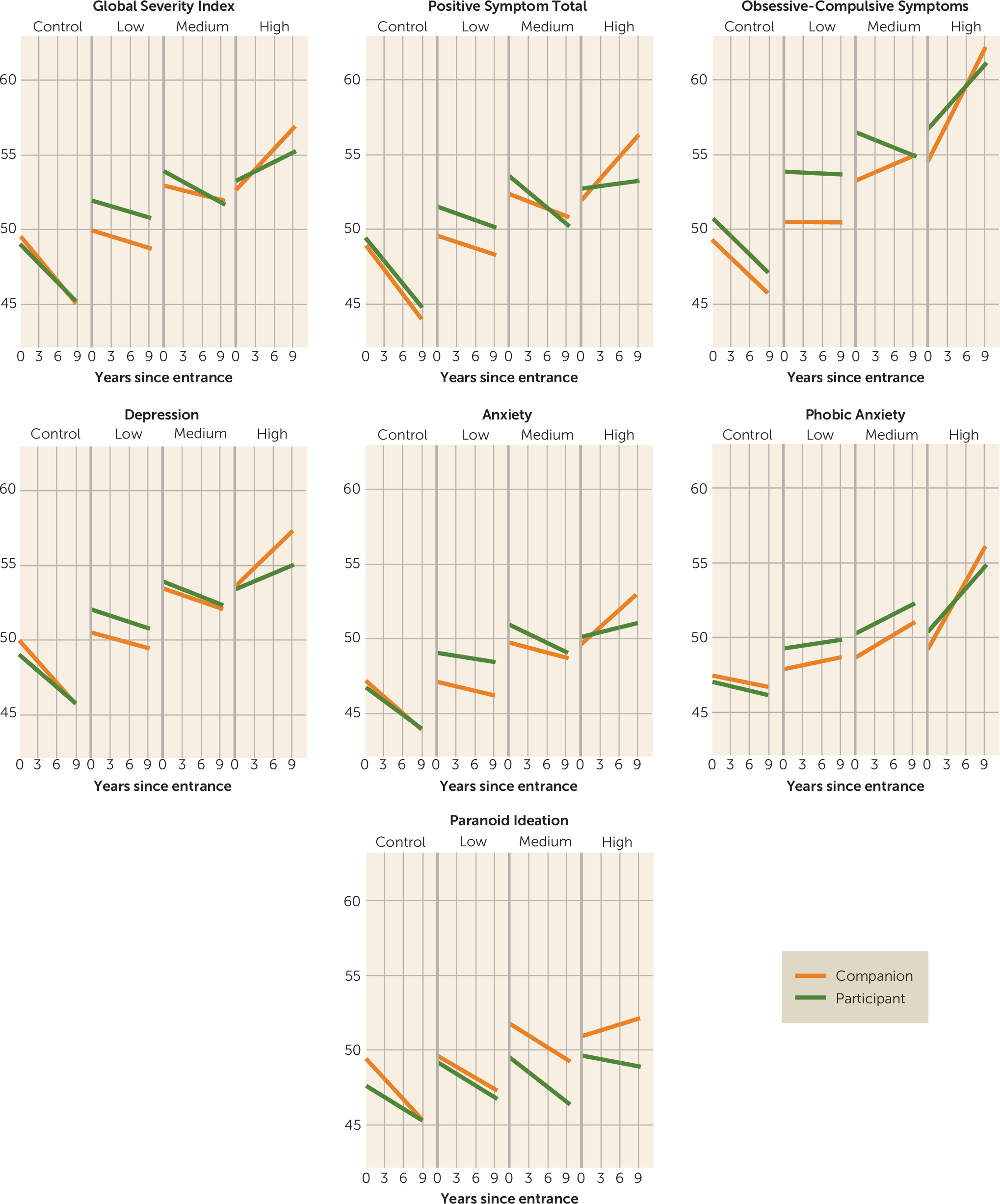

The present findings suggest that the source of measurement can significantly influence psychiatric measures in prodromal and diagnosed Huntington’s disease. All findings from this research were more robust when psychiatric symptoms were rated by companions (rather than self-reported by participants with the CAG repeat expansion) for those with prodromal Huntington’s disease. For instance, companion ratings worsened over time for 11 of 12 symptoms in the prodromal group with a high probability of imminent motor diagnosis, six of 12 symptoms in those with a medium probability of diagnosis, and two of 12 symptoms in those considered to be far from their estimated motor onset. Only seven of 12 participant ratings showed significant change over time, and only in the group in closest proximity to motor diagnosis. When analyses were conducted to examine the importance of discrepant ratings between companions and the prodromal participants, findings showed that ratings on seven of 12 psychiatric symptom scales were inconsistent between the raters. In participants closer to estimated motor onset, the companion ratings appear to be more valid, whereas in gene-mutation carriers who are furthest from estimated motor onset, self-reported psychiatric symptoms may be more appropriate.

These findings are consistent with cross-sectional observations that individuals with Huntington’s disease have decreased awareness of symptoms (

36–

39). It is important to note that even in carriers of the Huntington’s disease mutation who do not yet have a motor diagnosis, decreased awareness of both motor (

22) and psychiatric (

4) symptoms has been documented. The present study is the first to provide longitudinal data of reduced awareness in a prodromal Huntington’s disease cohort over such a long follow-up period. Our findings indicate that unawareness increases in concert with Huntington’s disease progression during the prodromal disease stages, as indicated by participant-companion differences arising mostly in the medium and high CAG-age product groups.

Difficulties with awareness or insight occur across the spectrum of neuropsychiatric disorders, including stroke, brain injury, dementia, psychosis, and mood disorders (

40). The etiologies of these disparate conditions vary, and it is not known whether there are common mechanisms that underlie the development of unawareness across disorders. Several studies in different disorders have noted associations between decreased awareness of symptoms and pathology in the right hemisphere, dorsolateral frontal regions, and, less often, the parietotemporal region. However, the findings are not consistent enough to indicate shared mechanisms with certainty. The results presented here and in other studies of Huntington’s disease symptoms and brain pathology are consistent with these anatomic findings, but more research is needed to support this connection. As described previously by others (

41), it is likely that neural networks connecting several regions are responsible for the phenomenon of decreased awareness. The presentation of lack of awareness also varies among disorders. In frontotemporal dementia, for example, insight is reduced early in the course of the illness, whereas in Alzheimer’s dementia this is a later manifestation (

42). Unawareness is also irreversible in dementias, whereas it is often transient in other disorders, such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, mood disorders, and schizophrenia. The progressive brain degeneration that occurs in Huntington’s disease may indicate that reduced insight is permanent, but additional study is needed to understand its course and causes.

There are some limitations to consider in the interpretation of these results. Some issues are related to the nature of the assessments. With the SCL-90-R, respondents are asked to provide ratings for the previous 7 days. As these measures were obtained annually, they may have missed episodes of psychopathology that occurred between assessments. While these findings support changes in participant-companion reporting over time, more detailed assessments at more time points would be beneficial. Another issue is related to potential rater biases. Both participants and companions were aware of participants’ Huntington’s disease genetic status, which may have affected their perception of symptoms. Sample selection bias may also affect the generalizability of these results. Only a fraction of individuals at risk for Huntington’s disease obtain genetic testing, which is required prior to enrollment in the PREDICT-HD study. There may be factors unique to those within the larger Huntington’s disease population who obtain genetic testing and participate in research studies. It is interesting to observe, however, that the sample in a recent study of pre-manifest Huntington’s disease in which genetic testing was not a requirement had demographic characteristics similar to our sample, including education levels (

43). Differences in awareness may also be present in our sample compared with the overall population. However, as previously described by Duff et al. (

4), it is equally likely that individuals with lower or higher awareness would participate in the study.

Despite these limitations, the results reported here provide initial information regarding psychiatric symptoms that occur in individuals who will develop Huntington’s disease and the importance of obtaining assessments from companions. This is critical to consider in future studies that assess behavioral manifestations and psychiatric symptoms, including those that investigate their underlying pathophysiology in Huntington’s disease and in therapeutic trials, as well as clinical assessment and management of persons who will develop Huntington’s disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the PREDICT-HD sites, the study participants, the National Research Roster for Huntington Disease Patients and Families, the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, and the Huntington Study Group.

The PREDICT-HD investigators, coordinators, motor raters, cognitive raters, executive committee, scientific consultants, and members of the core sections are listed at the end of the online data supplement.