The nosologic implications of irritability have received considerable attention in the child psychiatry literature in recent years, especially with regard to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in youths. Indeed, the diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) was introduced in DSM-5 in part to provide an appropriate diagnosis, distinct from bipolar disorder, for children with severe, nonepisodic irritability. By definition, the irritability seen in youths with DMDD is severe and relatively invariant over time. In contrast, some youths with bipolar disorder may have irritability while euthymic (i.e., trait irritability), and irritability may increase markedly during manic or depressive episodes (i.e., state-related irritability). Thus, while the clinical presentation of irritability differs between DMDD and bipolar disorder, the symptom is important in both disorders. However, it is unknown whether the neural mechanisms mediating irritability differ between DMDD and bipolar disorder; the question has potential treatment implications. In this study, we used a face emotion labeling paradigm to compare brain activation associated with irritability in DMDD and bipolar disorder.

Face emotion labeling deficits have been shown in both DMDD and bipolar disorder (

1–

5), particularly in response to less intense, ambiguous facial expressions (

6,

7). Indeed, one behavioral study found that irritability symptoms mediate the association between bipolar disorder and face emotion labeling deficits (

5). In addition, evidence suggests that DMDD and bipolar disorder may have distinct brain profiles when processing emotional faces, as youths with DMDD show less amygdala activation (greater deactivation) compared with youths with bipolar disorder (

8), as well as functional differences in other temporal, parietal, occipital, and prefrontal regions (

9,

10) associated with face processing (

11) and implicated in bipolar disorder (

12).

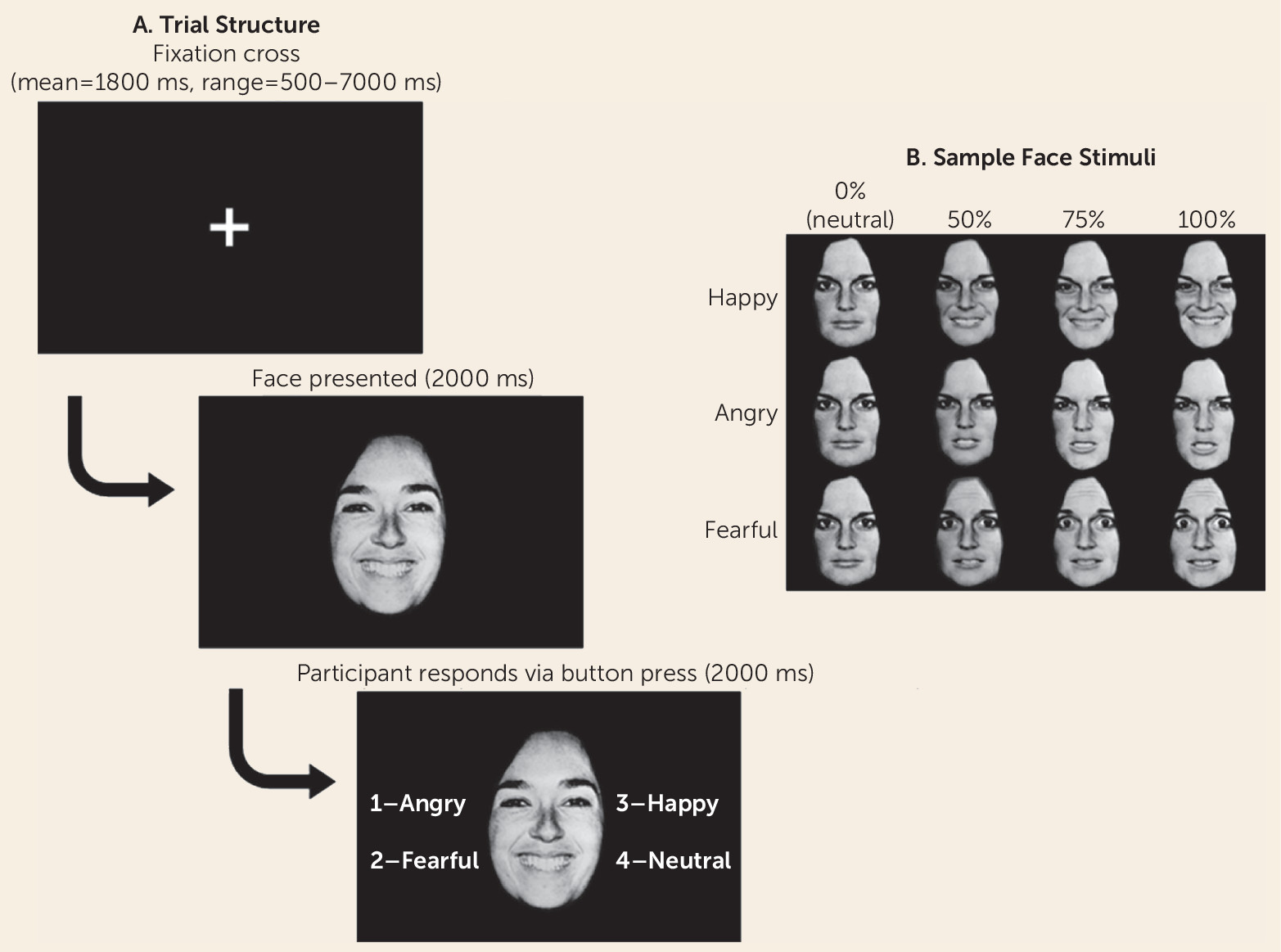

Our study addresses several gaps in the literature. First, whereas previous research has provided evidence that bipolar disorder and DMDD are pathophysiologically distinct (

8–

10), this study is the first to examine whether irritability is subserved by different neural mechanisms in these two patient groups. Second, although several functional MRI (fMRI) studies in DMDD and bipolar disorder have focused on face emotion processing (e.g.,

8,

13), this is the first to use a face emotion labeling scanning paradigm per se. It is important to scan face emotion labeling, as opposed to other aspects of face processing, because this is where behavioral deficits have been found in bipolar disorder and DMDD (

1–

6). Moreover, although previous work examined related constructs, such as trait aggression (

14), this study is the first, to our knowledge, to identify brain mechanisms of the irritability dimension. Also of note, previous studies on bipolar disorder, DMDD, and other disorders have identified ambiguous faces as important in eliciting group differences in emotion labeling processes (

6,

7), but they did not examine nonlinear patterns across emotional face intensity. As modeling nonlinear relationships may be necessary to fully capture pathophysiology (

15), this study models both linear and nonlinear patterns in brain activation across emotional face intensity.

Thus, this study compares neural correlates of irritability severity in DMDD, bipolar disorder, and healthy development. Youths with bipolar disorder, youths with DMDD, and healthy comparison youths performed a labeling task with happy, fearful, and angry faces of varying emotional intensity during fMRI acquisition. We hypothesized that activation elicited by emotional face labeling in the amygdala, as well as in other temporal and prefrontal regions previously identified as pathophysiologically distinct in DMDD and bipolar disorder (

8–

10), would be associated with irritability, but that this association would differ between DMDD and bipolar disorder, because the clinical presentation of irritability differs in these two disorders.

Discussion

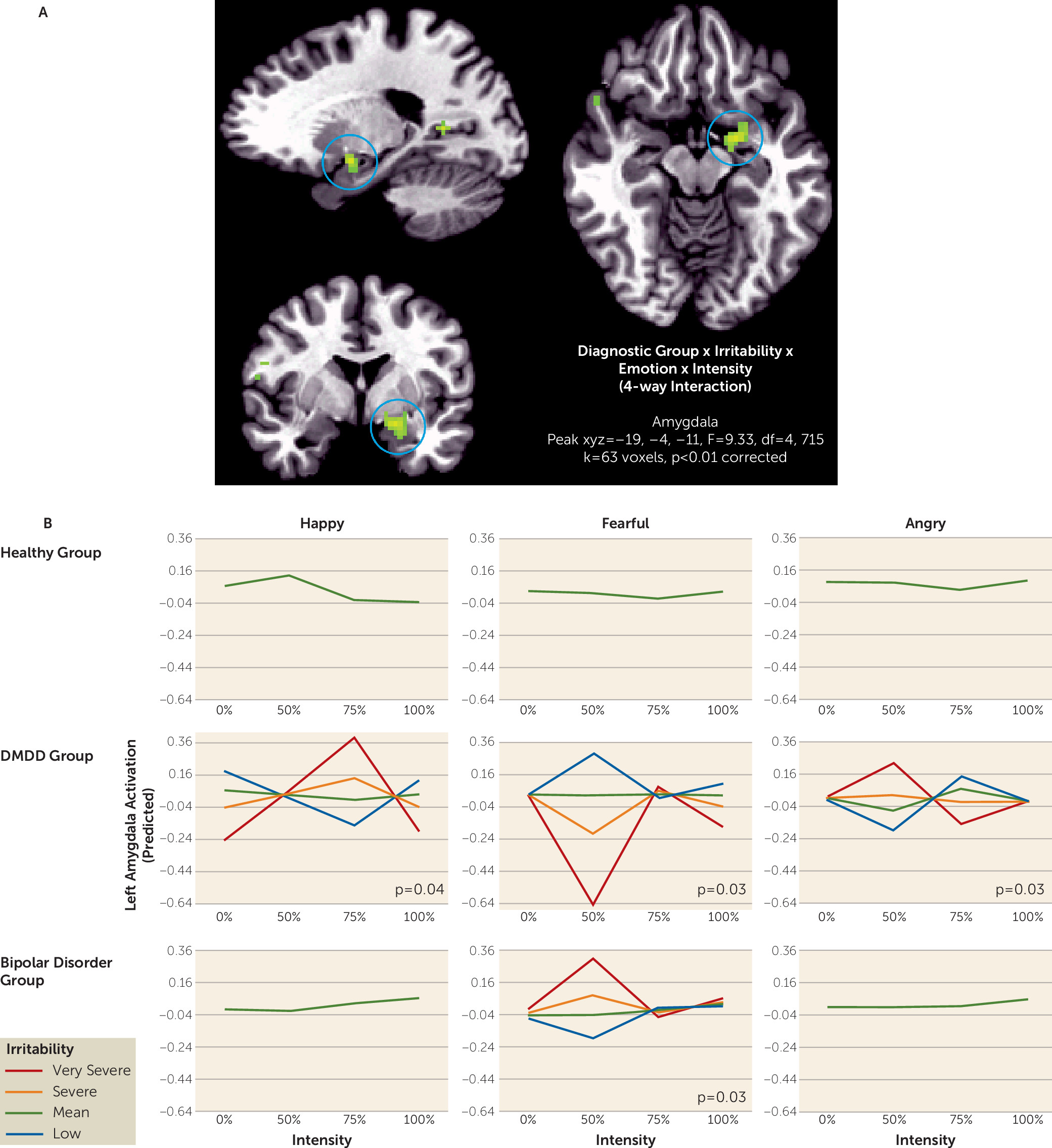

We demonstrated different brain activation patterns associated with irritability in DMDD compared with bipolar disorder when labeling emotional faces. Using a whole brain analysis, we observed divergent alterations in amygdala activation related to irritability in youths with DMDD and youths with bipolar disorder. In temporo-occipital regions that are important in face processing (

11), the DMDD group in particular showed associations between irritability and activation in response to ambiguous angry faces. Our findings extend previous work by using a novel paradigm and comparing the neural correlates of irritability, operationalized dimensionally, between bipolar disorder and DMDD.

This study has implications for our understanding of pathophysiological differences between DMDD and bipolar disorder. Eighteen of 24 youths with bipolar disorder in this study were euthymic when scanned, and the level of irritability was similar between the bipolar disorder and DMDD groups at the time of scanning. Thus, cross-sectionally in our samples, the irritability of the DMDD group could not be distinguished from that of the bipolar disorder group. However, previous research has shown that longitudinally, the pattern of irritability differs markedly between DMDD and bipolar disorder. Specifically, the defining feature of DMDD is persistent and severe irritability, whereas in bipolar disorder, the extent of irritability during euthymia can differ among individuals, and the degree of irritability across mood states can differ within an individual. In addition, the clinical course between bipolar disorder and DMDD differs in that youths with bipolar disorder have manic and depressive episodes, whereas such an outcome is unusual in patients with DMDD (

19). Our results indicate that these differences in clinical presentation and outcome are associated with different brain mechanisms mediating irritability. As with many psychiatric diagnoses, the diagnostic distinction between DMDD and bipolar disorder sometimes relies on retrospective recall, which can be fallible; this finding raises the possibility that brain imaging might eventually aid in the differential diagnosis.

Our results are largely consistent with previous findings suggesting that DMDD and bipolar disorder can be differentiated by brain response to emotional faces (

8–

10). Of note, divergent alterations in neural responses associated with irritability in DMDD compared with bipolar disorder were apparent when subjects correctly labeled subtle (50%−75% intensity) faces, not the overt (100% intensity) faces often used in face tasks. This may indicate that subtle, ambiguous social stimuli are necessary to capture differences in neural correlates, possibly because these faces are more difficult to identify correctly; consistent with this, treatment approaches drawing on the present findings, discussed below, focus on training responses to ambiguous faces. Overall, our findings suggest that even though both disorders feature irritability symptoms, DMDD and bipolar disorder are in fact distinct categories. Additionally, our finding of different neural correlates of irritability across diagnoses suggests that treatments may have to differ as well.

Although we showed overall pathophysiological differences between youths with DMDD and bipolar disorder, consistent with previous work (

8–

10), we failed to replicate findings of hypoactivation in the left amygdala to neutral faces the DMDD group (

8). This discrepancy may be due to key differences in the scanning paradigms between this study and previous work. Specifically, the psychological process probed in the paradigm used here (emotion labeling) differs from that of Brotman et al. (

8) (rating subjective fear). The present study focused on emotion labeling because behavioral deficits have been consistently found with emotion labeling in DMDD and bipolar disorder (

1–

5).

Our findings suggest that including information about the larger diagnostic context (i.e., DMDD versus bipolar disorder) may be essential to identify unique pathophysiological mechanisms of irritability symptoms. Indeed, an analysis that included only diagnosis showed no group differences, and another that examined the neural correlates of irritability irrespective of diagnosis found an association between irritability and response to the intensity of happy but not fearful or angry faces (see the online data supplement). Thus, these results suggest that in order to best capture the pathophysiology of irritability, it is necessary to consider both symptom measures and diagnosis.

Our results have potential treatment implications. The adverse effects of many new treatments (e.g., novel medications, brain stimulation) limit their use in children. Hence, it is particularly important to test noninvasive computer-based cognitive training techniques in children. Such techniques are developed by identifying perturbed psychological functions in a disorder, characterizing their associated neural correlates, and designing training regimens to alter symptoms and their associated neurocognitive correlates simultaneously. For example, attention bias modification treatment for anxiety disorders gained traction when investigators identified alterations in the engagement of threat circuitry in anxious patients (

20,

21); the present results delineate a parallel path for novel treatments in irritability.

Specifically, in this and previous studies, irritable youths showed face emotion labeling deficits (

1–

7) and associated perturbations in underlying neural circuitry (

8–

10). These deficits motivated the creation of cognitive training protocols designed to ameliorate the specific tendency of irritable youths to interpret rapidly presented ambiguous faces as angry (

22). In these training protocols, youths receive positive feedback for rating ambiguous faces on the happy-angry continuum as happy rather than angry. Such training shifts the patient’s judgment and was found to be associated with decreased irritability and anger in a double-blind controlled trial in youths at high risk for criminal offending (

23) and in an open trial of youths with DMDD (

22). These clinical findings in irritable youths are consistent with the DMDD-related dysfunction we found in the present study. In response to ambiguous faces, associations between irritability and neural activity differed between the DMDD and bipolar disorder groups in the amygdala, superior temporal sulcus, frontal pole, and lingual gyrus, all components of the ventral visual processing stream. In these regions, we found associations between neural activity in response to ambiguous angry faces and irritability in the DMDD group but not the bipolar disorder group. This suggests that training designed to normalize a tendency to interpret ambiguous faces as angry might be effective in DMDD, consistent with the existing data, but not in bipolar disorder. However, because of the lack of behavioral differences in this particular study, this conclusion should be considered tentative; further research will be needed to confirm it.

This study has several limitations. First, although it included data from three diagnostic groups, there were relatively few participants (Ns ranging from 22 to 25) in each group. These sample sizes are comparable to those of other fMRI studies on pediatric bipolar disorder (mean=19, SD=6.8) in a recent meta-analysis (

24), with Ns ranging from 10 to 32 participants. However, the results will need to be replicated with larger samples, which would also afford better coverage across the entire irritability dimension.

Second, psychotropic medication usage was very high, particularly in the bipolar disorder group, which could potentially affect results. Of note, when covarying number of medications, excluding individuals on each class of medications or including only the medication-free participants in the DMDD group (N=10; all but three youths in the bipolar disorder group were on medications), the results still stood (see the online data supplement). This decreases the likelihood that the results were primarily driven by medication usage, although definitive evidence would have to be drawn from a sample of medication-naive individuals with bipolar disorder and DMDD, which, given the high rates of medication usage, would be a challenge to recruit.

Third, among participants included in the imaging analyses, the groups did not differ significantly in emotion labeling accuracy, nor was accuracy related to irritability, unlike in previous behavioral studies (

1–

6). However, in order to obtain a robust estimate of brain activation, we included only those youths who had at least 62 time points in each condition after removing incorrect trials and censoring. In contrast, previous behavioral studies did not exclude participants for low accuracy. Indeed, when we included participants who had been excluded for insufficient data in each of the conditions (in part for poor performance), we found impaired emotion labeling ability in DMDD, consistent with previous studies (

1–

6).