Cannabis use and DSM-IV cannabis use disorders are associated with adverse consequences (

1,

2), including cognitive decline (

3–

5), impaired educational or occupational attainment (

6–

8), impaired driving ability (

9–

13), emergency room visits (

14), psychiatric symptoms (

15–

17), poor quality of life (

18), other drug use (

19), and risk of addiction or substance use disorders (

1). Despite this, Americans increasingly view marijuana use as harmless (

1,

20–

22) and support its legalization (

23). Reflecting these changing views, 23 states now have laws permitting marijuana use for medical purposes (of which four also legalized marijuana for recreational use). Marijuana use is more prevalent in these 23 states than in others (

24–

26). Consistent with these changes, marked increases have occurred in the U.S. prevalence of DSM-IV cannabis use disorder among veterans (

27) and adults in the general population (

28,

29). Cannabis-related emergency room visits and fatal car crashes have also increased (

11,

14).

To our knowledge, this report provides the first nationally representative information on DSM-5 cannabis use disorder using data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III (NESARC-III). This includes current and lifetime prevalences, age at onset, frequency of cannabis use among people with the diagnosis, demographic correlates, psychiatric comorbidity, disability, and likelihood of participation in interventions including professional treatment and 12-step programs.

Discussion

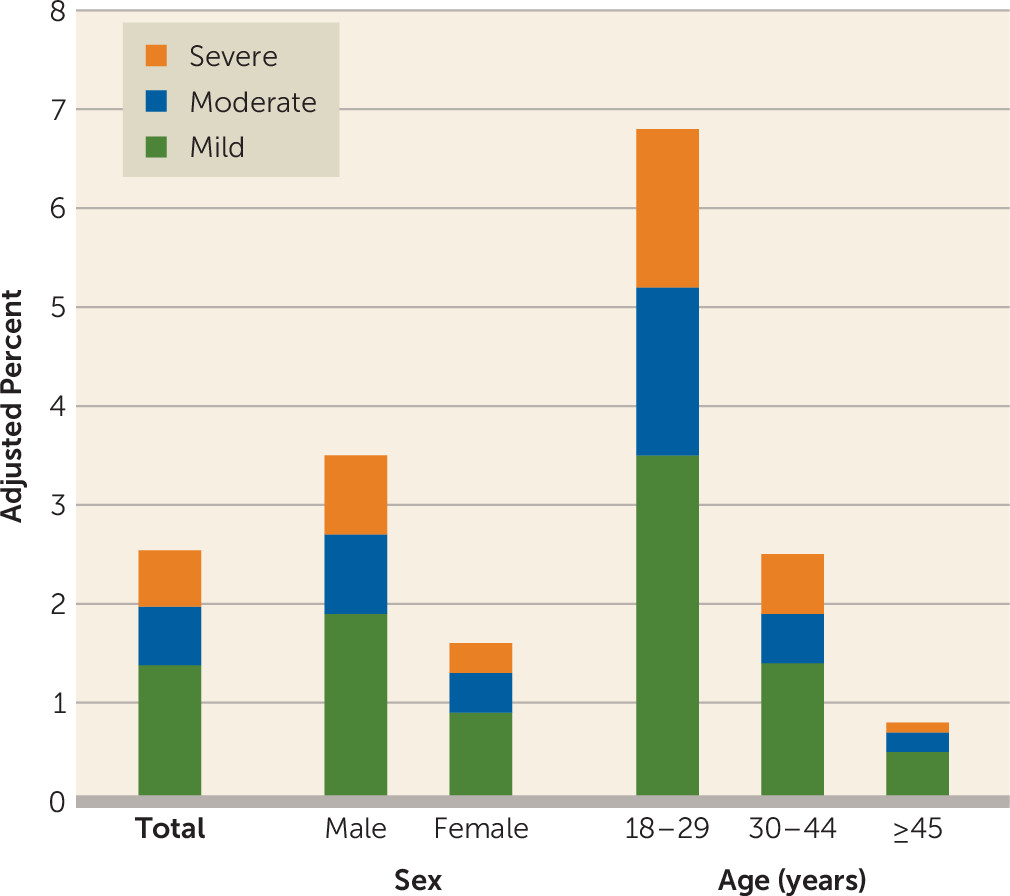

Among U.S. adults in 2012–2013, the 12-month prevalence of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder was 2.54%, representing approximately 5,982,000 Americans, and the lifetime prevalence was 6.27%, representing about 14,757,000 Americans. Corresponding DSM-IV 12-month and lifetime rates in NESARC-III, 2.9% and 11.7% (

29), showed that a substantial increase occurred since the 2001–2002 NESARC, in which the 12-month and lifetime rates were 1.5% and 8.5% (

29), an increase apparently driven by greater prevalence of cannabis users (

29).

The prevalence and odds of 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorders were greater among men than women, consistent with findings in earlier surveys (

17,

49,

50).

In NESARC-III, the odds for 12-month cannabis use disorder were higher among younger than older age groups, with striking differences between those age 18–29 and those ≥45 (OR=6.5–9.7). While the prevalence of cannabis use disorder increased across all age groups between the 2001–2002 NESARC and the 2012–2013 NESARC-III, the age differential in DSM-5 cannabis use disorder in NESARC-III is considerably more pronounced than in the NESARC (

17). The general increases suggest the operation of a period effect, while the sharply increased age differential suggests an additional cohort effect in the youngest adults. The general increase plus the sharp age differential in NESARC-III for DSM-5 cannabis use disorder are consistent with similar time trends among people favoring legalization of marijuana for recreational use (

51). These trends all appear to reflect different manifestations of the increasingly accepting social attitudes toward marijuana use.

The odds of cannabis use disorder varied by race or ethnic group. For 12-month and lifetime disorders, odds were lower for Asians or Pacific Islanders and for Hispanics than for whites, but higher in Native Americans, consistent with the NESARC data (

17). For blacks, the odds of 12-month cannabis use disorder were significantly higher than for whites, in contrast to findings in NESARC, in which blacks did not differ from whites. For lifetime cannabis use disorder, the odds did not differ between blacks and whites in NESARC-III, while in NESARC, blacks had significantly lower odds of lifetime cannabis use disorder than whites (

17). Thus, the risk in blacks relative to whites has increased over the past decade. This is consistent with notable increases in the prevalence of cannabis use and cannabis use disorders among blacks (

29,

52–

54). While the reasons for this change are unclear, increasing economic disparity between blacks and whites since the 2008 economic recession (

55,

56) may have exacerbated neighborhood factors (disorder, violence, visible drug dealing) that increase adolescent marijuana use (

57), and they may function similarly in adults, an issue warranting investigation. Blacks may also differ from whites in their attitudes toward marijuana, possibly viewing it as a natural and therefore safe substance (

22). This also warrants investigation.

Participants with the lowest incomes had higher odds of cannabis use disorder than others. Cannabis outcomes are related to income disparities in distal and proximal forms, including early exposure to disadvantaged macroeconomic environments (

58), low parental socioeconomic status as a moderator of the risk of family history of addiction (

59), and current residence in high-unemployment neighborhoods (

60). Cannabis disorders and concurrent economic disparity may be related if the stress of disadvantaged economic conditions leads to marijuana use as a coping mechanism, increasing the risk for cannabis use disorders among users with a vulnerability to such disorders. However, the relationship may be bidirectional, since early adolescent use of marijuana is associated with subsequent lower adult cognitive functioning (

3–

5), which could impair the chances for the educational and occupational achievement (

6–

8) that would bring higher incomes. This important yet complex relationship merits further study to inform policy and personal decisions regarding marijuana use.

Similar to the NESARC findings (

17), 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorders were strongly and consistently associated with other substance and mental disorders. Thus, despite the increasingly normative nature of marijuana use and the increased adult prevalence of cannabis use disorder, persons with cannabis use disorder continue to be vulnerable to other common mental disorders. In patient settings, those with both drug and psychiatric disorders often exhibit more persistent, severe, and treatment-resistant symptoms than patients with drug disorders only (

61). Research indicates that the best treatment for such comorbid conditions is concurrent treatment for both disorders (

61). Therefore, study findings indicate an increased need for settings that provide evidence-based treatments for both types of conditions. Further, multivariable investigation indicates two latent transdiagnostic domains of comorbidity, the internalizing and externalizing (

62) domains. The externalizing domain is characterized by antisocial personality disorder and substance disorders; the internalizing domain is characterized by distress (major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety) or fear (panic, social phobia, specific phobia). These domains have been replicated across gender and racial/ethnic groups (

63,

64). Given the changing legal and attitudinal climate in the United States regarding marijuana use, re-examining cannabis use disorders within this transdiagnostic framework is warranted to better understand its relationship to other substance and psychiatric disorders, and to inform the development of more effective treatments.

Participants with cannabis use disorder experienced considerable disability across different domains. The level of disability, particularly among those with severe disorders, was consistent with the very frequent cannabis use reported (252.2 and 310.4 days per year among those with 12-month and lifetime severe cannabis use disorders). These disability and use patterns attest to the severity of the disorder, which clearly is not a benign or harmless condition. Further, the disability levels were greater than the corresponding levels associated with alcohol use disorder in NESARC-III (

37). Previous research suggests that even after cannabis use disorders remit, disability persists (

65). Whether this persistence is mediated by prolonged cognitive impairments associated with early marijuana use (

3–

5), by aspects of the disorder itself (e.g., particular diagnostic criteria), or by other factors warrants investigation.

Relatively few participants with cannabis use disorder received any type of services, a situation unimproved since NESARC (

17). For alcohol use disorders, factors predicting lack of service use include viewing alcohol problems as stigmatized (

66) or not serious (

67), preference for self-reliance, and beliefs that treatment is ineffective (

67). Similar factors appear related to lack of service use for cannabis disorders (

30,

68), a topic warranting further investigation. Evidence-based treatments (

69–

71) are available for cannabis use disorders (

32). Public and professional education about treatment efficacy and availability that destigmatizes help seeking may encourage individuals with cannabis use disorders to seek treatment. Given the increased prevalence of these disorders among U.S. adults (

27,

29), provision of such services and public education about treatment appear critically needed.

The DSM-5 diagnosis of cannabis use disorder differs from that in DSM-IV by the addition of criteria for craving and cannabis withdrawal. Among participants with 12-month DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 60.50% (SE=2.05) had craving for cannabis, 32.48% (SE=2.09) had cannabis withdrawal, and 23.06% (SE=1.84) had both. In NESARC-III, the prevalence of moderate to severe DSM-5 cannabis use disorder was higher than the rate for DSM-IV cannabis dependence, a difference attributed to the cannabis withdrawal criterion (

72). Earlier studies showed how the craving and cannabis withdrawal criteria operate in the general population (

35,

73,

74); for instance, the model fit of cannabis use disorder criteria improved after addition of withdrawal (

75). While studies of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder in NESARC-III show good reliability and validity (

43,

45), further nosological studies focused on craving and withdrawal should be conducted with the NESARC-III data.

NESARC-III findings of increased rates of cannabis use disorder (

29) are inconsistent with the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which found that the prevalence of cannabis use disorder was stable between 2002 and 2013 (

7). However, the NESARC-III findings are consistent with other national indicators of increases in cannabis use disorders (

27) and other serious cannabis-related problems, e.g., emergency room visits and fatal car crashes (

11,

14). These increases are consistent with a changing landscape of increasingly permissive marijuana attitudes and laws. Changing laws may benefit society by reducing the harms of socially patterned drug arrests (

76). However, the laws may affect public health adversely by leading to more marijuana users, including some vulnerable to cannabis use disorders. Continued surveillance of these trends is needed to monitor the balance of social costs and benefits and the needs for treatment.

Lifetime rates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder were highest in those ages 18–29. This could be artifactual due to recall failure for earlier disorders among older individuals (

77). However, this report and others (

17) show that the risk for onset of cannabis use disorder peaks in late adolescence and early 20s, and remission often occurs within 3–4 years (

17,

78). Given that, the finding of higher rates of lifetime disorders among those ages 18–29 may well be valid. Further studies are needed to address this issue.

Study limitations are noted. Only common psychiatric disorders were assessed. Some population segments were not included, e.g., prisoners, the homeless, and long-term inpatients. NESARC-III was also cross-sectional. Prospective surveys are needed to investigate the stability and causal directions of the relationships. The study also did not distinguish between associations explained by greater use of cannabis and those due to greater risk of a disorder given such use; future studies should address this issue. NESARC-III also had important strengths, including a large sample, reliable and valid measures, and rigorous field methodology. NESARC-III is also unique in providing current, comprehensive information on DSM-5 cannabis use disorder and its correlates and comorbidity in the U.S. adult general population.

In summary, DSM-5 cannabis use disorder is a highly prevalent, comorbid, disabling disorder that commonly goes untreated. Numerous risk factors were identified that could stimulate further studies of differences in correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder by sex, age, and race/ethnicity, which could inform additional hypothesis-driven studies. Most important, this study highlights the urgency of identifying and implementing effective prevention methods. The study also highlights the need to educate the public, professionals, and policy makers about the seriousness of cannabis use disorder and the need for public health efforts to destigmatize and encourage help seeking for cannabis use disorder among individuals who cannot reduce their use of marijuana on their own, despite substantial harm to themselves and others.