Adolescence is a high-risk period for the emergence of depression. Prospective studies show a marked increase in rates of depression from childhood through adolescence (

1), and epidemiological studies indicate that the lifetime prevalence of depression in adolescence is approximately 11%−14% (

2). Sex differences in depression arise in early to mid adolescence, and by the end of adolescence, rates of depression are twice as high in females as in males (

3). Adolescence provides a unique opportunity to examine risk factors for depression before the marked increase in disorder incidence and symptoms, especially in girls, who exhibit the sharpest rise in risk.

There are several well-established psychosocial risk factors for adolescent depression, including previous depressive symptoms (

4), other psychiatric disorders (e.g., anxiety and behavioral disorders) (

5), and a family history of psychiatric disorders (

6). However, these risk factors rely on subjective reporting of symptoms and history, are not specific to depression, and do not capture all the variance in risk. Indeed, a majority of high-risk youths will not develop a depressive disorder. To address this issue, there has been growing interest in identifying biomarkers that are more closely related to the etiopathogenesis of depression and can aid in early identification and prevention efforts (

7).

Abnormalities in the brain’s reward system are central to many etiological models of depression (

8). Depressed and dysphoric adults, relative to healthy comparison subjects, exhibit a decreased behavioral response to reward (

9) and reduced brain activation in regions critical to reward processing, including the caudate and ventral striatum (

10,

11). Similarly, depressed children and adolescents, relative to healthy comparison subjects, exhibit a diminished neural response in multiple reward-related brain regions (

12). Several studies have indicated that youths with a family history of depression, an established indicator of risk (

6), exhibit a reduced neural response to rewards (

13,

14).

A blunted neural response to rewards has also been shown to predict the development of adolescent depression. Two longitudinal studies using functional MRI (fMRI) found that decreased striatal activation to reward predicted greater depressive symptom scores 2 years later in adolescents (

15,

16). Another fMRI study found that decreased striatal activation in anticipation of reward predicted the development of subthreshold or clinical depression 2 years later in previously healthy adolescents (

17). Together, these studies support a blunted neural response to rewards as a potential mechanistic biomarker of adolescent depression. However, it is still unclear whether this marker provides incremental predictive value relative to other well-established risk factors (e.g., previous depressive symptoms, family history of psychiatric disorders).

Event-related potentials (ERPs) are another tool for examining neural response to rewards, and they have the advantage of being obtainable in almost all children and adolescents across development. The reward positivity is a positive deflection in the ERP signal that occurs approximately 250–350 ms following feedback indicating monetary gains that is absent or reduced following losses (

18,

19). Research has indicated that the reward positivity corresponds with activation in key reward-related brain regions, including the medial prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum (

20). This ERP component has also been known as the feedback error-related negativity, feedback negativity, and medial frontal negativity, and in previous investigations it was commonly measured as the difference between the ERP response to losses and gains (i.e., losses minus gains). However, recent evidence has indicated that the ERP response to gains and losses is composed of multiple overlapping components (e.g., P200, P300) that do not differ following gains and losses; rather, the reward positivity is present on gain trials but is absent or reduced on loss trials (

21). Therefore, to better isolate the reward positivity, researchers have begun to examine the difference between the ERP response to gains and losses (gains minus losses), with greater (i.e., more positive) values indicating increased reward sensitivity (

18).

In children and adolescents, a smaller reward positivity has been associated with family history (i.e., risk) of depression (

22,

23) and has been found to prospectively predict major depressive episodes in adolescents (

24). In addition, a smaller reward positivity has been shown to be cross-sectionally (

25) and prospectively (

24,

26) associated with increased depressive symptom scores in adolescents. These studies support the reward positivity as a neural vulnerability marker of adolescent depression. However, this evidence is still inconclusive because of methodological limitations, including cross-sectional analyses, small samples, and suboptimal measures (e.g., telephone screen diagnostic measures [

24]).

In this study, we tested whether the reward positivity predicted first-onset depressive disorder and greater depressive symptom scores 18 months later in adolescent girls. Building on previous smaller studies (

24,

26), we sought to rigorously characterize this effect in a large community-based sample (N=444) assessed with state-of-the-art diagnostic measures. In addition, we examined whether the reward positivity predicted the development of depression independent of other major risk factors, including previous depressive symptoms (

4) and adolescent and parental lifetime psychiatric history (

5,

6). We hypothesized that a smaller reward positivity at baseline would uniquely predict an increased likelihood of developing first-onset depressive disorder and greater depressive symptom scores 18 months later. Finally, we examined whether the reward positivity had incremental predictive value relative to other psychosocial risk factors by determining whether it provided increased sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value for the development of first-onset depressive disorder.

Method

Participants

The overall cohort consisted of 550 girls between ages 13.5 and 15.5 years (mean=14.4 years, SD=0.63) and their parents (one biological parent for each girl), participating in a longitudinal study of risk for adolescent depression. Most participants (80.5%) were non-Hispanic Caucasians, and a majority (57.8%) of parents had at least a bachelor’s degree. Participants were recruited from the community using a commercial mailing list of homes with 13- to 15-year-old girls, word of mouth, local referral sources (e.g., school districts), online classified advertisements, and community postings. Inclusion criteria were fluency in English, ability to complete questionnaires, and a biological parent willing to participate. Exclusion criteria were intellectual disability or lifetime history of major depressive disorder or dysthymia, as the study aimed to predict first-onset depression. Families were financially remunerated for participation. Informed assent and consent were obtained from adolescents and parents, respectively, and the study was approved by the Stony Brook University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The adolescents’ psychiatric history was ascertained with the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) (

27). The K-SADS-PL was administered to the adolescent by trained interviewers who were closely supervised by clinical psychologists (R.K., D.N.K., and G.P.). There was no exclusion of participants who met diagnostic criteria for any nondepressive psychiatric disorders. At the 18-month follow-up assessment, the K-SADS-PL was administered again to the adolescent to assess change in diagnostic status across the interval. The present study focused on first-onset depressive disorder (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified). To determine the reliability of diagnoses, 29 baseline K-SADS-PL interviews were audio-recorded and scored by a second rater who was blind to the original diagnoses. Interrater reliability was excellent, ranging from 0.51 (for social phobia) to 0.83 (for specific phobia).

Parental psychiatric history was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (

28). The SCID was administered at the baseline assessment to the biological parent accompanying the participant (93.9% mothers) by trained interviewers who were closely supervised by clinical psychologists (R.K., D.N.K., and G.P.). The interrater reliability for 25 audio-recorded interviews was excellent, ranging from 0.62 (for generalized anxiety disorder) to 1.00 (for dysthymia).

Adolescent depressive symptoms were assessed with the expanded version of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (

29), which is a 99-item factor-analytically derived self-report inventory of empirically distinct dimensions of depression and anxiety symptoms. Symptoms are rated for the past 2 weeks on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The present study focused on dysphoria, the core symptom dimension of depression (

30), which is assessed by the 10-item dysphoria subscale of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms.

Procedure

At baseline, the adolescents completed the K-SADS-PL, the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, and the doors task (described below). The accompanying parent completed the SCID. At the 18-month assessment, the K-SADS-PL and Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms were administered to the adolescents once again.

Doors task.

The doors task, which was administered using Presentation, version 17.2 (Neurobehavioral Systems, Albany, Calif.), consisted of three blocks of 20 trials. Each trial began by presenting two identical doors. Participants were instructed to select the left or right door by clicking the left or right mouse button, respectively. Participants were told that they could either win $0.50 or lose $0.25 on each trial. The image of the doors was presented until participants made a selection. Next, a fixation cross was presented for 1000 ms, and feedback was subsequently presented for 2000 ms. A gain was indicated by a green arrow pointing upward and a loss by a red arrow pointing downward. The feedback stimulus was followed by a fixation cross presented for 1500 ms, immediately followed by the message “Click for next round.” This prompt remained on the screen until participants responded with a button press to initiate the next trial, ensuring that participants remained active and engaged during the task. There were 30 gain and 30 loss trials.

EEG recording and processing.

EEG recording and processing parameters were consistent with previous investigations of the reward positivity (

24). Continuous EEG was recorded using an elastic cap with 34 electrode sites placed according to the 10/20 system. Electro-oculography (EOG) was recorded using four additional facial electrodes: two placed approximately 1 cm outside of the right and left eyes and two placed approximately 1 cm above and below the right eye. Sintered Ag/AgCl electrodes were used. EEG and EOG were recorded using the ActiveTwo system (BioSemi, Amsterdam) and digitized with a sampling rate of 1024 Hz using a low-pass fifth-order sinc filter with a half-power cutoff of 204.8 Hz. For the EEG electrodes, a common mode sense active electrode producing a monopolar (nondifferential) channel was used as a recording reference. The EOG electrodes produced two bipolar channels that measured horizontal and vertical eye movements.

EEG data were analyzed using BrainVision Analyzer, version 2.1 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). Data were referenced offline to the average of left and right mastoids, band-pass filtered (0.1 to 30 Hz), and corrected for eye movement artifacts (

31). Feedback-locked epochs were extracted with a duration of 1000 ms, beginning 200 ms before feedback presentation. The 200 ms prestimulus interval served as the baseline. Epochs containing a voltage greater than 50 μV between sample points, a voltage difference of 300 μV within a segment, or a maximum voltage difference of less than 0.5 μV within 100 ms intervals were automatically rejected. Additional artifacts were identified and removed based on visual inspection.

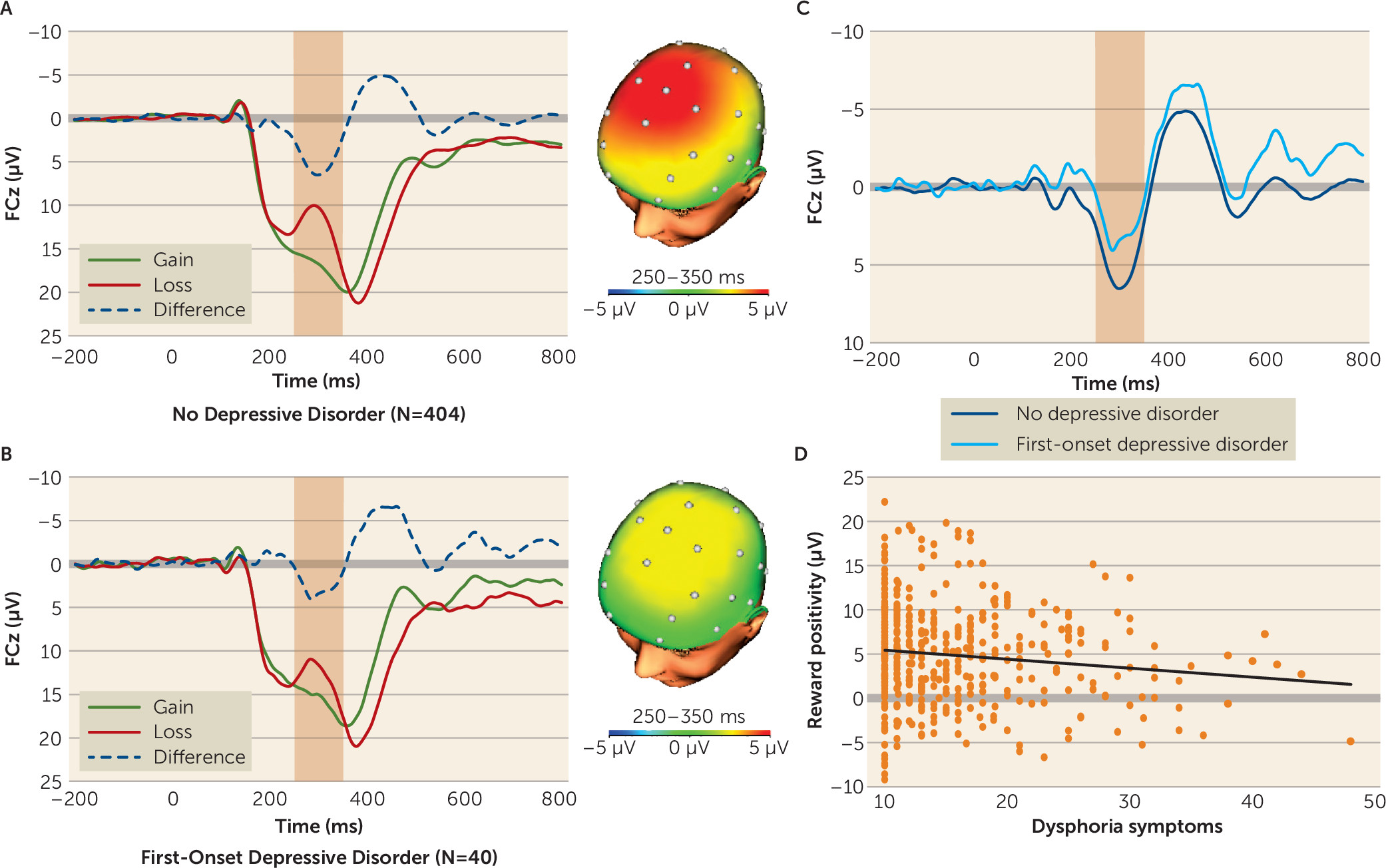

Feedback-locked ERPs were averaged separately for gains and losses and scored as the mean amplitude from 250–350 ms following feedback at FCz, where the difference between gains and losses was maximal. The reward positivity was then quantified as the difference between gain and loss trials (gains minus losses).

Data Analysis

Participants were excluded from the analyses if they had a lifetime history of depressive disorder not otherwise specified at baseline (N=34), were missing diagnostic interview or self-report data at baseline or the 18-month follow-up assessment (N=38), did not complete the doors task (N=30), or had outlier reward positivity values that were more than three standard deviations from the mean (N=4), resulting in a final sample of 444 participants.

Logistic and linear regressions were conducted to determine whether the reward positivity predicted first-onset depressive disorder and dysphoria symptoms, respectively. Multiple regression was conducted to determine whether these associations were independent of other risk factors. The reward positivity was converted to a negative number, such that more positive values indicated a reduced reward positivity, to better compare it with other risk factors. The reward positivity and dysphoria symptoms were z-transformed before logistic regressions were conducted, to allow for direct comparison of odds ratios.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were conducted to determine area under the curve, sensitivity, and specificity for baseline predictors in relation to first-onset depressive disorder. These values were used in combination with the prevalence of first-onset depressive disorder in this sample to calculate positive and negative predictive value. The reward positivity and dysphoria symptoms were continuous measures; therefore, multiple sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated based on a range of cutoffs (+0.5, +1.0, +1.5, and +2.0 standard deviations from the mean). Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, N.Y.).

Results

Table 1 lists rates of lifetime psychiatric disorders at baseline in the participating adolescents and parents. At the 18-month follow-up assessment, 40 participants (9.0%) had experienced a first-onset depressive disorder, including major depressive disorder (N=18, 4.1%), dysthymia (N=7, 1.6%), and depressive disorder not otherwise specified (N=24, 5.4%). Among participants who developed a depressive disorder, compared with those who did not, dysphoria symptoms were greater both at baseline (mean score on the dysphoria subscale of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, 20.76 [SD=8.37] compared with 15.63 [SD=6.40]; t=3.77, df=442, p<0.001) and at the 18-month follow-up (mean score, 25.42 [SD=9.88] compared with 14.57 [SD=5.49]; t=6.84, df=442, p<0.001). There were no significant differences between these two groups in age, ethnicity, and parental education.

Across participants, the ERP response to monetary gains was greater (i.e., more positive) than the response to losses (mean amplitude, 16.95 µV [SD=9.32] compared with 12.09 µV [SD=8.57]; t=18.59, df=443, p<0.001). As shown in

Figure 1, a smaller reward positivity predicted a greater likelihood of developing first-onset depressive disorder (odds ratio=1.60, 95% CI=1.13–2.27, p<0.01) and greater dysphoria symptoms (β=0.12, p<0.01) at 18 months. In addition, as shown in

Table 2, the reward positivity predicted both measures of depression independent of all other risk factors. These results indicate that a blunted reward positivity prospectively predicted both categorical first-onset depressive disorder and greater continuous dysphoria symptoms 18 months later, and these effects were independent of other prominent risk factors.

Following previous studies (

18), the reward positivity was computed as the difference between ERP responses to gains and losses. Neither the ERP response to gains alone nor the response to losses alone predicted first-onset depressive disorder or dysphoria symptoms.

At baseline, 20 participants (4.5%) were taking psychotropic medications (anxiolytics, N=1; anticonvulsants, N=1; antidepressants, N=4; stimulants, N=12; other medications, N=2), and by the 18-month follow-up assessment, 29 participants (6.5%) were taking psychotropic medications (anxiolytics, N=2; anticonvulsants, N=1; antidepressants, N=12; stimulants, N=15; other medications, N=2). To determine whether psychotropic medication use affected the results, we included medication use (coded as 0 if present and 1 if absent) at baseline and at the 18-month follow-up assessment as covariates. The reward positivity continued to predict first-onset depressive disorder and greater dysphoria symptoms at the 18-month follow-up assessment even after controlling for psychotropic medication.

Depressive disorders and generalized anxiety disorder are among the most frequently comorbid disorders and share substantial genetic liability (

32). To determine the specificity of the relationship between the reward positivity and depression, we examined whether it also predicted first-onset generalized anxiety disorder. We excluded 13 participants with lifetime generalized anxiety disorder at baseline, resulting in a sample of 431 participants. At the 18-month follow-up assessment, 25 participants had experienced first-onset generalized anxiety disorder. The reward positivity did not predict first-onset generalized anxiety disorder, supporting the specificity of its association with depression.

Table 3 lists sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for the baseline risk factors predicting first-onset depressive disorder at the 18-month assessment. Both the reward positivity and dysphoria symptoms provided high specificity and negative predictive value but relatively low sensitivity and positive predictive value. To determine the incremental predictive value of the reward positivity over dysphoria symptoms—the only other significant predictor of first-onset depressive disorder—we examined their combined performance when applied in parallel (i.e., if either test is positive, the individual has the disease) and in series (i.e., if both tests are positive, the individual has the disease). As shown in

Table 4, parallel testing produced increased sensitivity but decreased specificity, using a low cutoff value for the reward positivity and dysphoria symptoms. There was little change in positive and negative predictive value. Conversely, series testing produced increased specificity but decreased sensitivity, using a high cutoff for the reward positivity and dysphoria symptoms. Notably, series testing also provided significantly increased positive predictive value (45.0%) relative to the reward positivity (18.6%) or dysphoria symptoms (26.1%) alone when cutoff values were 1.5 and 2 standard deviations from the mean, respectively. Negative predictive value remained high irrespective of testing approach or cutoff.

Discussion

In a sample of 444 adolescent girls with no lifetime history of depressive disorder, a blunted reward positivity at baseline prospectively predicted first-onset depressive disorder and greater dysphoria symptoms 18 months later. More importantly, the reward positivity predicted the development of depression independent of other prominent risk factors, including baseline dysphoria symptoms and both adolescent and parental lifetime psychiatric history. The reward positivity also provided incremental positive predictive value for first-onset depressive disorder when applied in series with baseline dysphoria symptoms. Overall, the results of this study support a blunted reward positivity as a viable mechanistic biomarker of adolescent-onset depression.

The reward positivity is a neural measure that reflects activation of a reinforcement learning system used to adjust future behavior (

33). A blunted reward positivity in adolescents may indicate deficient reward sensitivity, which consequently diminishes the tendency to engage in approach-oriented behaviors or to pursue pleasurable activities (e.g., socialization with peers), which would buffer the effect of stress. Since adolescence is a period characterized by heightened stress due to physical maturation, brain development, and environmental and social changes (

34), a reduced sensitivity to reward may exacerbate the deleterious effects of such stress, which could in turn contribute to the development of depression (

35). It is important to note that the reward positivity difference score, and not the ERP response to gains or losses alone, predicted the development of depression. While this difference score approach has been shown to best isolate the reward positivity (

21), it is also possible that the results were due to reduced neural reactivity to all types of feedback (i.e., reduced positivity to gains and decreased negativity to losses).

Together with previous fMRI studies (

15–

17), the present study provides strong converging evidence that a blunted neural response to rewards precedes the emergence of adolescent-onset depression. The reward positivity may be an economical brain-based target for screening and prevention efforts, particularly since psychotherapy (

36) and psychopharmacological (

37) treatments have been shown to improve neural reward sensitivity deficits. Furthermore, the reward positivity demonstrated discriminant validity and did not predict the development of first-onset generalized anxiety disorder. These results are consistent with previous research indicating that the reward positivity is uniquely associated with adolescent depression and not anxiety (

38). However, reward system dysfunction has been implicated in other disorders (e.g., externalizing disorders) (

39), and additional research is needed to better understand whether the reward positivity is a biomarker of other forms of mental illness. This study only supports the reward positivity as a biomarker of adolescent depression at the group level, and a higher threshold of evidence is required to determine its utility at the individual level.

The reward positivity predicted first-onset depressive disorder and greater dysphoria symptoms independent of adolescent baseline dysphoria symptoms and adolescent and parental lifetime psychiatric disorder histories. These results suggest that a blunted neural response to rewards indexes a distinct vulnerability from other well-established psychosocial risk factors. In addition, the reward positivity provided a nearly twofold increase in positive predictive value of first-onset depressive disorder when combined in series with baseline dysphoria symptoms. In a clinical or research setting, the temporal ordering of these screening measures could be conducted in a cost-effective manner. For example, all patients might initially complete a self-report measure of dysphoria symptoms, and those with elevated symptoms would receive the secondary assessment of reward system functioning. This is merely an illustrative example, and additional research is needed to identify the optimal combination of biological, demographic, and psychosocial risk factors in the prediction of adolescent-onset depression.

This study had several limitations. First, the sample was limited to a largely homogeneous sample of girls 13–15 years old, and the results may not generalize to other populations. Second, baseline dysphoria symptoms were a stronger predictor of the development of depression than was the reward positivity, but this was not surprising given the lack of shared method variance between the reward positivity and depression measures. Furthermore, the follow-up assessment was conducted over a relatively short interval (18 months), and it is possible that the reward positivity will become a stronger predictor as more participants develop depressive disorders. Third, the specificity analyses may have been underpowered, as only 25 participants developed first-onset generalized anxiety disorder during the follow-up. Finally, parental psychiatric history was assessed in only one parent, primarily mothers, which limited the assessment of parental risk.