Major depressive disorder is a highly prevalent illness and is often associated with significant morbidity and mortality. While a number of therapies are available for treatment of major depression, a major limitation of all existing antidepressants is delayed onset of action (

1). In addition, despite recent advances in the pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment of major depression, up to 35% of patients fail to respond to drug therapy (

2). Depression that does not respond to two or more different antidepressant drugs at adequate dosage and duration, which has been termed treatment-resistant depression, has a significantly lower likelihood of responding to another antidepressant (

3).

Ketamine is a noncompetitive,

N-methyl-

d-aspartate glutamate receptor antagonist that has been approved for use as an anesthetic (

4). Recent studies with ketamine have demonstrated a rapid onset (2–24 hours postinfusion) of antidepressant effect (

5–

8). The effect is relatively short-lived, however, and how to sustain ketamine’s efficacy for a longer duration through an optimal long-term dosing regimen has not yet been determined. At the time this study started, most previous studies that had assessed the efficacy of ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression were randomized controlled trials using a single dose; the duration of response in these studies ranged from 3 to 17 days after dosing (

5,

9). More recently, Murrough et al. (

7) assessed the sustained antidepressant effect in an open-label period using a thrice-weekly regimen over a 2-week period and found that response was maintained in most patients (median time to loss of response, 18 days; 24th and 75th percentiles, 11 and 27 days). In another study, patients receiving six infusions over a 12-day period demonstrated a gradual increase in response rate (25% after the first dose, 58.3% after three doses, 91.6% after six doses), with time to loss of response ranging from <7 to >28 days (

10). The lowest dosing frequency that could sustain the antidepressant response is not known. A once-weekly dosing interval is unlikely to sustain the response, at least initially, because the average duration of response after a single-dose infusion is less than 1 week (

9).

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of two dosing regimens—twice a week and three times a week—of intravenous ketamine (at 0.5 mg/kg of body weight) compared with placebo in sustaining initial antidepressant efficacy in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Secondary objectives were to assess the onset of antidepressant response and the safety of repeated doses of ketamine in this population.

Method

Patients

The study enrolled men and women 18 to 64 years of age who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for recurrent major depressive disorder without psychotic features, confirmed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (

11). Additional inclusion criteria were qualifying valid depressive episodes, as assessed with the SAFER criteria (

12) (defined as state versus trait, assessability, face validity, ecological validity, and rule of three Ps—pervasive, persistent, and pathological); inadequate response to at least two antidepressants (with at least one antidepressant failure in the current episode), assessed by medication history and the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (

13); and a score ≥34 on the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Clinician Rated (

14,

15) at screening and pre-infusion assessment on day 1. Independent SAFER raters from Massachusetts General Hospital verified that all randomized patients met the SAFER criteria, had treatment-resistant depression documented on the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire, and manifested the required depression severity.

Key exclusion criteria were a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa, or bulimia nervosa or a prior history or current diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, mental retardation, borderline personality disorder, mood disorder with postpartum onset, or somatoform disorders. Other exclusion criteria were a history of previous nonresponse of depressive symptoms to ketamine, clinically significant suicidal or homicidal ideation (imminent risk of harm), and substance abuse or dependence within the year preceding the screening visit.

Independent ethics committees or institutional review boards at each site approved the protocol. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles based on the Declaration of Helsinki and consistent with Good Clinical Practices and applicable regulatory requirements. All patients confirmed understanding of the study procedures and provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Study Design

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 2 study conducted at 14 sites in the United States between July 2012 and September 2013. The study consisted of four phases: an up-to-4-week screening phase, a 4-week double-blind treatment phase (day 1 to day 29), an optional 2-week open-label treatment phase, and an up-to-3-week ketamine-free follow-up phase. The maximum study duration for each patient was 13 weeks. During the double-blind treatment phase, patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to one of the four treatment groups: intravenous ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) two or three times weekly or intravenous placebo (0.9% sodium chloride for injection) two or three times weekly, administered over 40 minutes. Study drugs were administered on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 15, 18, 22, and 25 for the twice-weekly regimen and on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 10, 12, 15, 17, 19, 22, 24, and 26 for the thrice-weekly regimen. Randomization was based on a computer-generated randomization scheme, balanced by the use of randomly permuted blocks and stratified by study center. The investigators, patients, and all study staff were kept blind to assigned treatment at randomization. An unblinded pharmacist was accountable for study drug preparation to ensure the integrity of blinding.

Patients fasted overnight (≥8 hours) before study drug administration, until 2 hours after the start of infusion. Based on the investigators’ clinical judgment, participants, who were generally outpatients throughout the study, could be admitted on the day before dosing. Patients were discharged after completion of the pharmacokinetic blood sampling (i.e., 6 hours after dosing on days 1 and 15) or at least 4 hours after start of the infusion on other dosing days. Patients who had completed the study at least through the day 15 visit in the double-blind treatment phase but had discontinued the study before the day 29 visit because of lack of efficacy were allowed to participate in an optional open-label treatment phase to receive intravenous ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) at the same dosing frequency for an additional 2 weeks. Patients continued any antidepressant medications they were receiving at screening, at the same stable dosages throughout the study. For patients who entered the optional open-label phase, a follow-up visit occurred 1 week after the last dose; for patients who received at least one dose during the double-blind phase but did not enroll in the optional open-label phase, follow-up visits occurred 1, 2, and 3 weeks after the last dose.

Study Evaluations

Efficacy assessments.

The primary endpoint was the change from baseline to day 15 (at pre-infusion assessment) in score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (

16) in the double-blind phase. A 7-day recall period was used for the measurement of MADRS at baseline, whereas a 24-hour recall period was used for measurements at other time points. The secondary efficacy endpoints included early onset of clinical response (number of patients with an improvement ≥50% from baseline in MADRS score during week 1 that was maintained through day 15), total number of responders at each time point up to day 15 (number of patients with a ≥50% reduction from baseline in MADRS score), and total number of remitters at day 15 (number of patients with a MADRS score ≤10) in each ketamine group compared with the respective placebo group. Other secondary efficacy endpoints included the change in MADRS score from baseline through day 29, change at each time point and at endpoint in the Clinical Global Impressions severity score (CGI-S) (

17,

18), CGI improvement score (CGI-I) (

17,

18), change in the Patient Global Impression severity score (PGI-S) (

19), and Patient Global Impression of Change score (PGI-C) (

18). During the open-label phase, in the twice-weekly group, the MADRS, CGI-S, and CGI-I were administered on day 4 and the PGI-S and PGI-C on days 4, 8, and 11; in the thrice-weekly group, the MADRS, CGI-S, and CGI-I were administered on days 3 and 5 and the PGI-S and PGI-C on days 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12.

Safety assessments.

Safety was assessed by treatment-emergent adverse events, laboratory tests, vital signs (including pulse oximetry monitoring), physical examinations, ECG monitoring, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale positive symptom subscale (BPRS+) (

20), and the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) (

21).

Pharmacokinetic assessments.

Venous blood samples were collected at prespecified time points (before dosing and up to 6 hours after dosing on day 1 and on day 15) to measure plasma concentrations of ketamine and norketamine (the active metabolite of ketamine) (using a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method with a quantification range of 0.5–500 ng/mL).

The following noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated for both ketamine and norketamine: observed maximum plasma concentration (Cmax); time to reach Cmax (tmax); area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time 0 to 6 hours postinfusion (AUC6h).

Statistical Analysis

All efficacy analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat set, which included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study drug during the double-blind phase and for whom data were available for both the baseline assessment and at least one postbaseline assessment. Patients who entered the open-label treatment phase were included in the open-label intent-to-treat analysis set. The safety analysis set included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study drug.

Assuming a treatment difference of ≥8 points in the mean change from baseline to endpoint in MADRS score between the ketamine and placebo groups, 14 patients were required in each group in order to detect this treatment difference with a power of 90% at an overall one-sided p value of 0.15 (common in phase 2 studies) based on a two-sample t test. Thus, a total of 56 patients were to be recruited across the four treatment groups.

For MADRS score, imputation of any missing individual item scores was applied. For all other scales, if any item of the scale was missing on one visit, the total score for that scale at that visit was left blank. The primary efficacy endpoint and the change from baseline in MADRS score to day 29 were analyzed using a mixed-effect model with repeated measures, with baseline MADRS score as a covariate, center and time-by-treatment interaction as fixed effects, and patient as a random effect. The threshold for detecting a therapeutic signal was based on least-squares means using a one-sided alpha of 0.15. For each time point, descriptive statistics were provided for MADRS score and changes from baseline. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

The proportion of patients who had an onset of clinical response within the first week in each ketamine group was compared with the corresponding placebo group using the exact Mantel-Haenszel test. The analysis of the change in CGI-S and PGI-S scores was performed using a rank-based analysis of covariance model, whereas the analysis of CGI-I and PGI-C scores was performed using a rank-based analysis of variance model.

The plasma concentrations of ketamine and norketamine and their corresponding noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters were summarized using descriptive statistics. Statistical analyses were performed to compare the Cmax and AUC6h values on day 15 with those on day 1.

Results

Patients

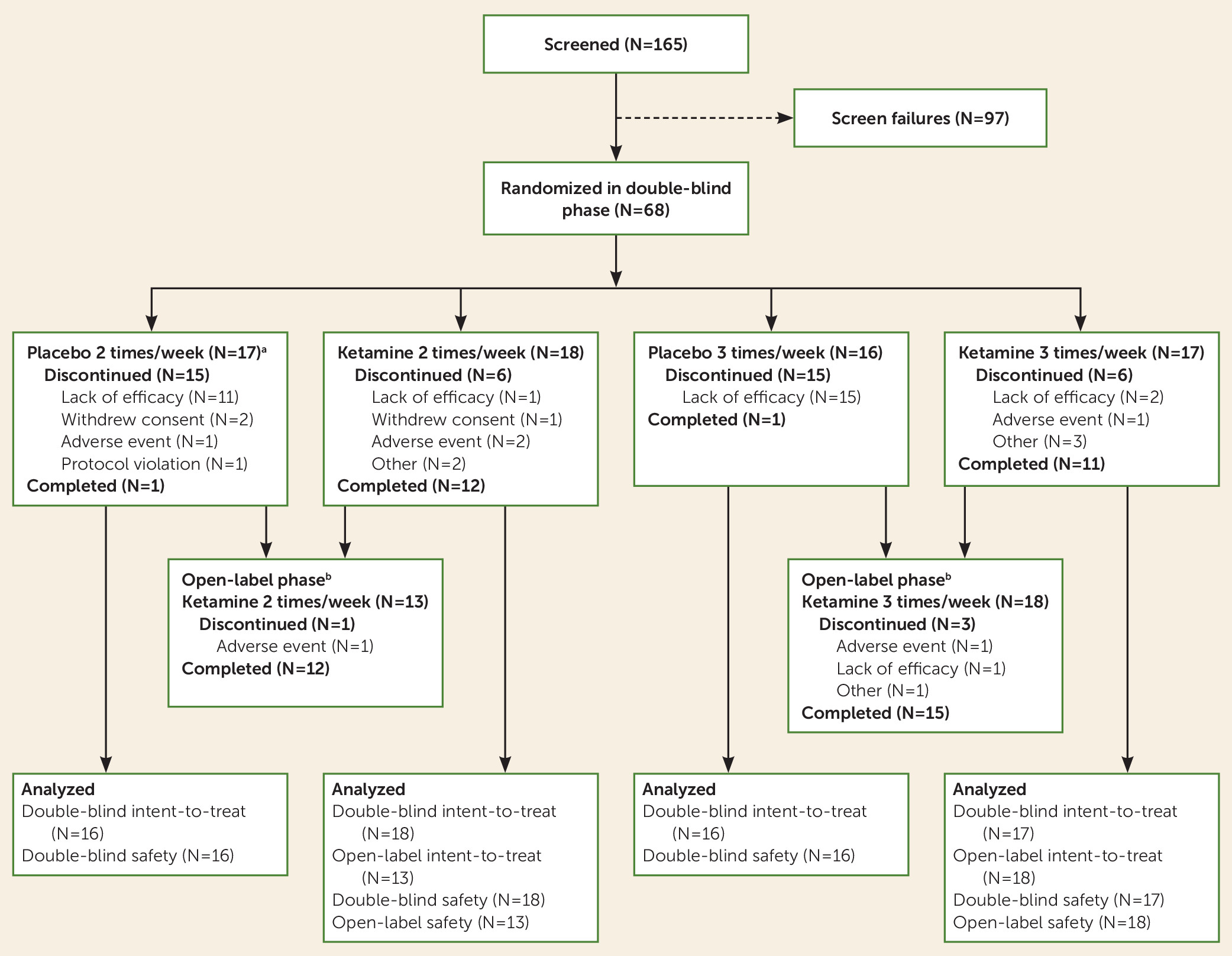

A total of 165 patients were screened for eligibility, and 68 were randomized into the four arms of the double-blind phase (

Figure 1). A total of 57 (83.8%) patients completed the first 15 days of the double-blind phase, and 25 (36.8%) patients completed the 4-week double-blind phase as planned. After day 15, patients who had not responded had the option of moving to the optional 2-week open-label phase. The majority of patients who discontinued before day 29 withdrew because of lack of efficacy, and most of them were receiving placebo (total dropouts, N=29; twice-weekly groups: ketamine, N=1; placebo, N=11; thrice-weekly groups: ketamine, N=2; placebo, N=15). In both of the frequency groups, more patients treated with ketamine than with placebo continued up to week 3 and week 4 in the double-blind phase (week 3: twice-weekly ketamine, N=14; placebo, N=4; thrice-weekly ketamine, N=15; placebo, N=1; and week 4: twice-weekly ketamine, N=13; placebo, N=2; thrice-weekly ketamine, N=13; placebo, N=1). Of the 31 patients enrolled in the optional open-label phase, 27 (87%) completed it.

Overall, baseline demographic and clinical characteristics did not differ significantly across the treatment groups (

Table 1). In the entire sample, the mean age was 43.9 years (SD=11.0), and 67.2% (N=45) of the patients were women. The mean MADRS score at baseline was 35.2 (SD=5.1). The antidepressants most commonly used (>10% of patients in each treatment group) at baseline were fluoxetine, citalopram, and bupropion; these agents were continued throughout the study.

Primary Outcomes

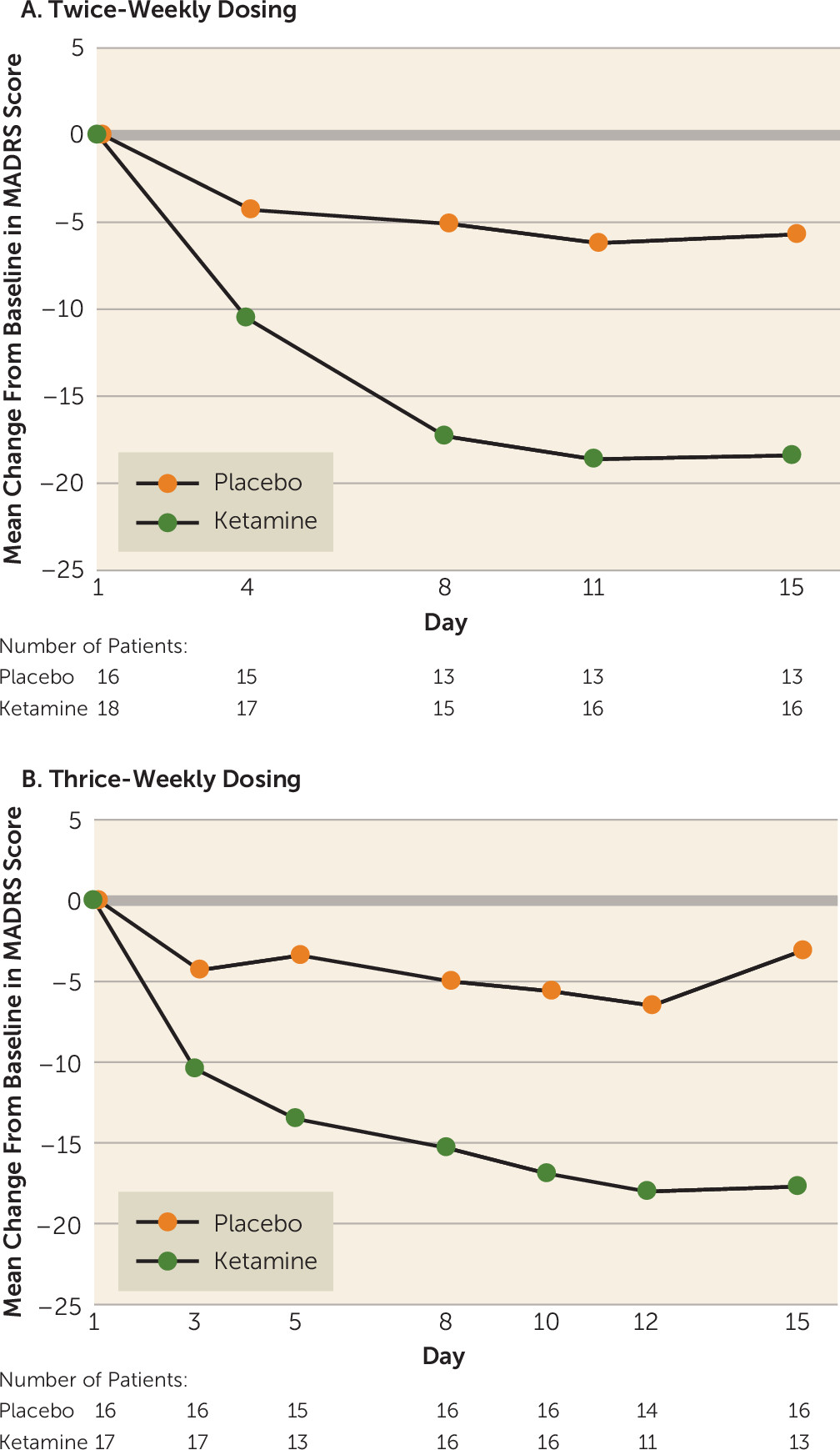

The mean change in MADRS score from baseline to day 15 was significantly improved in both ketamine frequency groups compared with the respective placebo groups (twice-weekly ketamine: −18.4 [SD=12.0]; placebo: −5.7 [SD=10.2]; p<0.001; thrice-weekly ketamine: −17.7 [SD=7.3]; placebo: −3.1 [SD=5.7]; p<0.001). The difference of least-squares mean change from baseline was −16.0 (SE=3.7) in the twice-weekly ketamine group and −16.4 (SE=2.4) in the thrice-weekly ketamine group compared with the respective placebo groups, and the difference was progressive through the first 8–11 days (

Figure 2). Overall, the mean difference in MADRS scores did not differ between the two frequencies tested.

Secondary Outcomes

The mean change in MADRS score (last observation in the double-blind phase carried forward) improved from baseline to day 29 for both ketamine groups (twice-weekly ketamine, −21.2 [SD=12.9]; placebo, −4.0 [SD=9.1]; thrice-weekly ketamine, −21.1 [SD=11.2]; placebo, −3.6 [SD=6.6]).

Onset of a clinical response within week 1 that was maintained through day 15 was observed in a higher proportion of patients in both ketamine groups compared with the respective placebo groups (

Table 2). Additionally, the proportion of responders and remitters was higher in both ketamine groups compared with the respective placebo groups. The CGI-S and PGI-S scores decreased significantly (p<0.05, one-tailed) in both ketamine groups compared with the respective placebo groups. The CGI-I and PGI-C scores showed significant improvement (p≤0.01) in both ketamine groups compared with respective placebo groups.

During the open-label ketamine phase, both groups showed improvement in mean MADRS score compared with baseline, and the change in both frequency groups was similar (twice-weekly, −12.2 [SD=12.8] on day 4 of open-label treatment; thrice-weekly, −14.0 [SD=12.5] on day 5 of open-label treatment) (see Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). Similarly, during the ketamine-free follow-up phase, MADRS scores were generally comparable between the two ketamine groups (see Table S1). MADRS scores over time for individual patients from double-blind baseline to day 18 of the follow-up phase are presented in Figure S1 in the data supplement.

During the 2-week open-label ketamine phase, the mean CGI-S and PGI-S scores were similar in both groups. The mean CGI-I and PGI-C scores for both ketamine groups were also similar in the open-label phase.

Pharmacokinetic Outcomes

The pharmacokinetic profiles of ketamine and norketamine were similar between treatment regimens (twice compared with thrice weekly) and study days (day 1 compared with day 15) (see Figure S2 and Table S2 in the online data supplement). The Cmax for ketamine ranged from 168 to 219 ng/mL, and the Cmax for norketamine ranged from 63.5 to 77.3 ng/mL. The plasma AUCs for ketamine and norketamine were similar across the treatment groups and study days (mean AUC6h of ketamine: range, 293–342 h∙ng/mL; norketamine: range, 232–265 h∙ng/mL). Individual Cmax and AUC6h values of ketamine (both dosing regimens) showed no significant correlation with individual body weight (data not shown).

Safety

During the double-blind phase, treatment-emergent adverse events were higher in both ketamine groups compared with the respective placebo groups (twice-weekly ketamine, 83.3%; placebo, 56.3%; thrice-weekly ketamine, 76.5%; placebo, 50.0%) (

Table 3). No deaths were reported. Serious treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in two patients in the twice-weekly ketamine group (anxiety [life event related] leading to hospitalization on day 12 in one patient and suicide attempt on day 40 [i.e., more than 4 weeks after last dose] in the other patient). Neither of these adverse events was considered by the study’s responsible physician to be related to ketamine. Discontinuation due to treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in two patients (11.1%) in the twice-weekly ketamine group (anxiety, N=1; anxiety, paranoia, and palpitation, N=1), one patient (6.3%) in the twice-weekly placebo group (intervertebral disc degeneration), and one patient (5.9%) in the thrice-weekly ketamine group (anxiety, dizziness, hypoesthesia, and feeling cold). No treatment discontinuations due to adverse events occurred in the thrice-weekly placebo group. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (≥20% patients in any treatment groups) were headache, anxiety, dissociation, nausea, and dizziness (

Table 3). These adverse events typically occurred on the days of dosing and in general dissipated within 2 hours from start of dosing.

During the ketamine open-label and ketamine-free follow-up phases, the proportion of treatment-emergent adverse events was similar in both groups; no serious adverse events were reported. Treatment-emergent adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in two patients (nausea in one [twice-weekly ketamine group] and irritability in the other [thrice-weekly ketamine group]). The onset of most of the adverse events occurred on dosing days in all four groups (data not shown). Mean changes in pulse rate and blood pressure were within normal limits for all patients in the four treatment groups. No clinically significant changes in laboratory tests, pulse oximetry, and ECG were observed during the study.

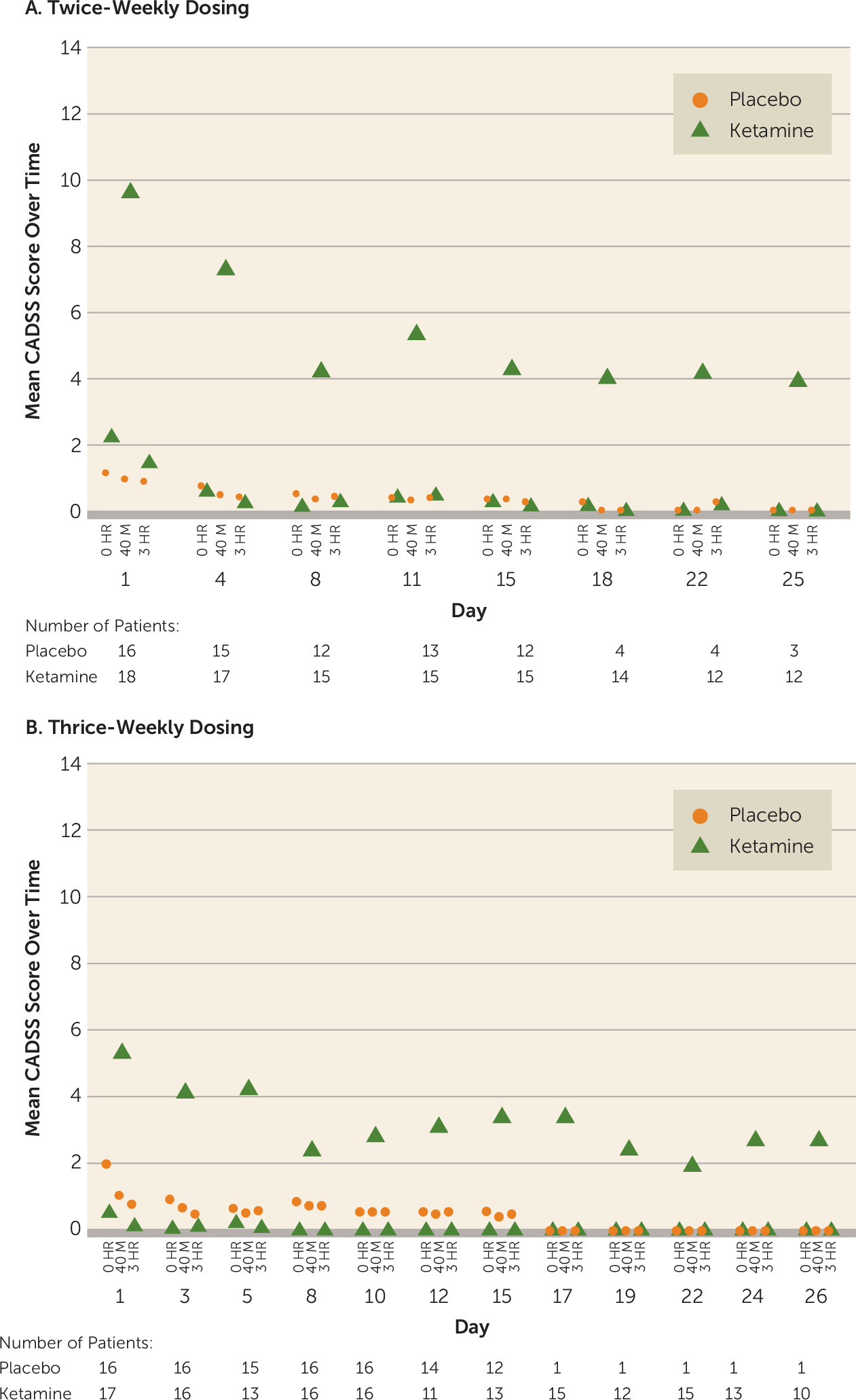

During the double-blind and open-label phases, dissociative symptoms (measured by change in CADSS total score) were observed shortly (40 minutes) after start of the infusion and resolved by 3 hours postinfusion (

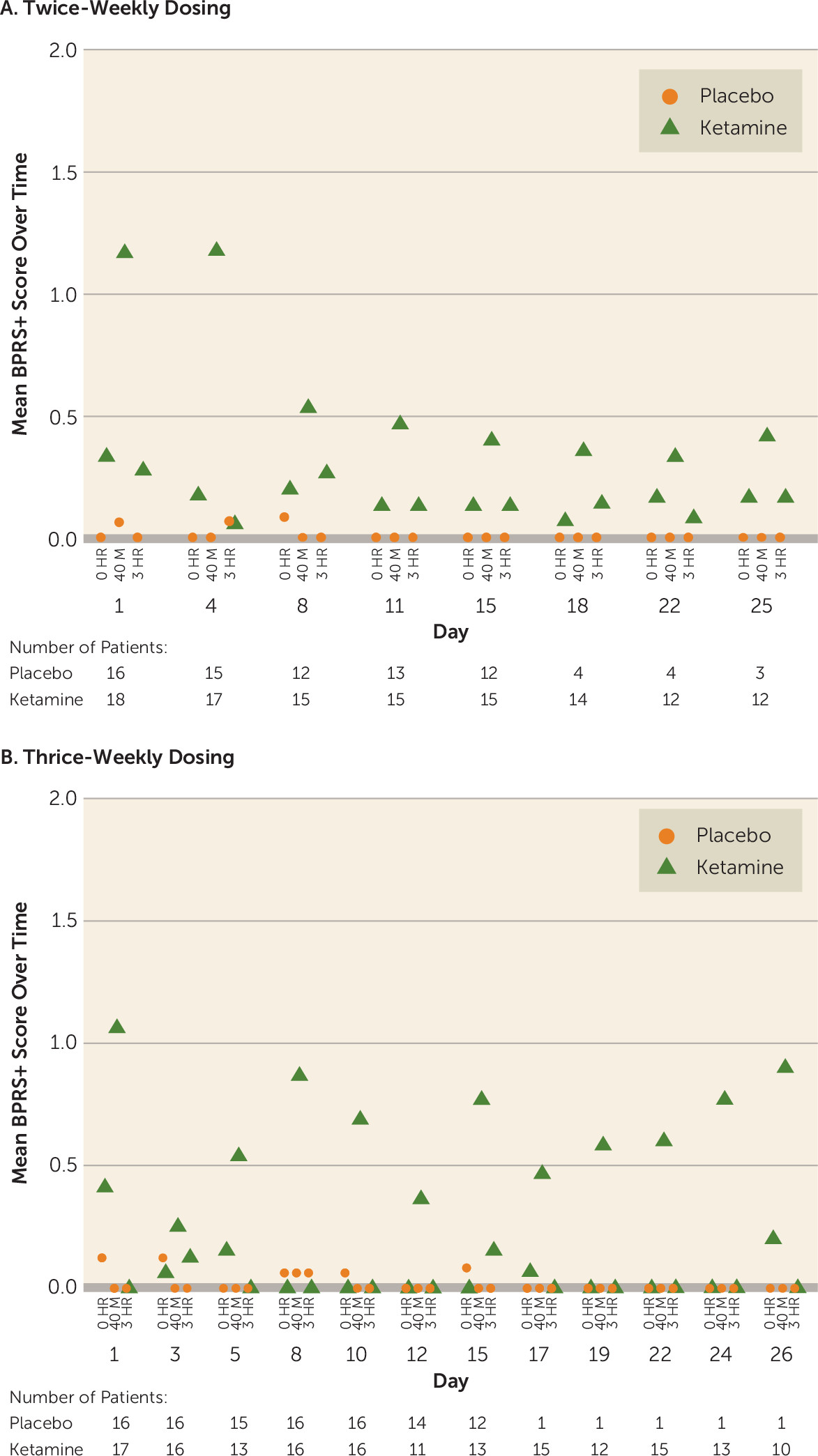

Figure 3). The intensity of dissociative symptoms diminished with repeated dosing (CADSS total score at 40 minutes: twice-weekly group, mean=9.6 [SD=9.31] on day 1 compared with mean=4.3 [SD=6.43] on day 15; thrice-weekly group: mean=5.3 [SD=6.75] on day 1 compared with mean=3.4 [SD=5.27] on day 15). No delusions or hallucinations were observed during the study. Similarly, BPRS+ scores returned to the pre-infusion values at the 3-hour postinfusion assessment in the two ketamine frequency groups in both the double-blind and open-label phases (BPRS+ score at 40 minutes: twice-weekly group, mean=1.2 [SD=2.15] on day 1 compared with mean=0.4 [SD=0.83] on day 15; thrice-weekly group: mean=1.1 [SD=1.61] on day 1 compared with mean=0.8 [SD=1.92] on day 15) (

Figure 4). An improvement in suicidal ideation (measured by the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale) was observed in all four treatment groups (see Table S3 in the

data supplement).

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of two dosing regimens of ketamine at 0.5 mg/kg administered intravenously over 40 minutes in sustaining the antidepressant effects of ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression beyond the initial dose. Once-weekly administration was not tested, as previous data have shown an average duration of effect of 5 days after a single dose of ketamine (

8). At day 15, MADRS score was significantly improved in patients receiving ketamine compared with those receiving placebo; the two dosing frequencies (twice and thrice weekly) were equally successful in sustaining the antidepressant response throughout the study period. The mean improvement in MADRS score in both ketamine groups was progressive through the first 8–11 days and was consistent through all time points (

Figure 2). Because the effect size of the antidepressant signal did not differ significantly between the two dosing frequencies, a twice-weekly initiation treatment regimen appears to be sufficient as an initial repeated-dose strategy in patients with treatment-resistant depression.

A previous multiple-dose pilot study evaluated six doses (thrice weekly) of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression for 2 weeks and reported response rates of 62.5% (first dose) to 70.8% (sixth dose) (

7). Another study with a similar treatment session regimen reported a gradual increase in response rate from 25% (first dose) to 92% (sixth dose) (

10). In the present study, we evaluated repeated intravenous doses with two different dosing regimens and observed response rates of 68.8% for twice-weekly dosing and 53.8% for thrice-weekly dosing at day 15. Thus, although the study designs differ, a progressive increase in response rate beyond the first dose was also observed here.

Overall, analyses of primary and secondary endpoints showed better efficacy for ketamine compared with placebo during the double-blind phase; the results also appeared similar across the study groups. Few patients remained in either placebo group at day 29. Most of the participants receiving placebo were nonresponders and discontinued from the study after day 15 because of lack of efficacy and then received 2 weeks of open-label ketamine treatment, per protocol. However, among the patients who continued placebo across the double-blind period, a subset appeared responsive to placebo. The efficacy results in the open-label and follow-up phases appeared consistent with the double-blind treatment phase. Those who responded or remitted maintained the efficacy for the 4-week follow-up under either twice-weekly or thrice-weekly ketamine regimens.

The safety and tolerability of ketamine was consistent with earlier reports in patients with treatment-resistant depression (

5,

7–

9). Our study was not powered to detect a significant difference in the treatment-emergent adverse event profiles between the two ketamine groups. No deaths occurred. During the double-blind phase, patients receiving twice-weekly ketamine reported two serious treatment-emergent adverse events of anxiety and suicide attempt, with the latter occurring more than 4 weeks after the last dose. Overall, the treatment-emergent adverse events appeared similar in frequency in the double-blind and open-label phases (headache, nausea, dizziness, etc.). Acute transient psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms were also observed, which usually resolved within 2 hours, consistent with earlier reports (

8,

9). The intensity of dissociative/perceptual change treatment-emergent adverse events, as assessed using the CADSS, decreased with consecutive doses.

Several limitations of our study merit comment. The study had a relatively short duration and assessed the induction and maintenance of response for only 4–6 weeks. Treatment-resistant depression is a chronic condition, and studies with a longer duration are warranted to fully characterize whether the clinical benefits of ketamine can be maintained, and if so, whether they can be sustained despite reductions in the dosing frequency during chronic treatment. Additionally, no active control was used in the study. This is a limitation of all studies with multiple doses of ketamine, as the adverse events associated with ketamine conceivably may unblind the active drug administration to patients and/or clinicians. Finally, the aim of the study was to assess the efficacy of two dosing regimens that differed only in frequency of administration, although it was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference between the two regimens.

Conclusions

Ketamine, administered intravenously at 0.5 mg/kg of body weight either two or three times weekly, appeared comparably effective in both achieving rapid onset and maintaining antidepressant efficacy in patients with treatment-resistant depression across the 15-day period of assessment for the primary efficacy endpoint. The improvement was similar in the two frequency groups. As less frequent treatment administration is usually preferred in order to reduce the patient and clinic burden and costs, this result, taken together with other data acquired during the double-blind and open-label phases, suggests that the twice-weekly treatment regimen administered for 4 to 6 weeks can induce and maintain (through day 15) a robust antidepressant effect in the treatment-resistant depression population. Overall, both treatment regimens were generally tolerable, with significant attenuation of the dissociative adverse events across repeated infusions. Studies of the sustained effects over longer periods are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Pravin Bolshete, B.A.M.S., and Shalini Nair, Ph.D. (SIRO Clinpharm Pvt. Ltd.) for writing assistance and Wendy Battisti, Ph.D., and Ellen Baum, Ph.D. (Janssen Research and Development) for additional editorial support in the development of this manuscript. The authors thank all the investigators and co-investigators who took part and contributed to data collection in this study, as well as the study participants, without whom the study would never have been accomplished.