Irritability—a heightened propensity to anger, relative to peers—is a common reason for referral to mental health services and is strongly associated with impairment and long-term adverse outcomes (

1–

6), yet it remains a nosological and treatment challenge (

1,

2). Currently, it is treated as a homogeneous construct; however, it is a core or accompanying feature of several psychiatric disorders, and such differential associations suggest that subtyping may be necessary. The purpose of this study was to examine the possibility that there are multiple forms of irritability, including a “neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like” type, with onset in childhood, and a “depression/mood” type, with onset in adolescence.

Our aim in this study was to take advantage of a longitudinal population-based cohort and use a developmental approach to test the hypothesis that there are at least two forms of irritability: one neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like type with onset in childhood and one depression/mood type with onset in adolescence. Specifically, we used a latent growth-modeling approach to test the following hypotheses suggested by this formulation of irritability: 1) an irritability trajectory defined by an early age at onset would be associated with male sex, ADHD genetic liability as indexed by ADHD genetic risk scores (polygenic risk scores [PRSs]), and a higher rate of diagnosis of ADHD in childhood; and 2) an irritability trajectory defined by an age at onset around early to mid-adolescence would be associated with female sex, depression genetic liability as indexed by depression genetic risk scores, and a diagnosis of depression in adolescence.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated developmental trajectories of irritability across childhood and adolescence to test the hypothesis that there are different forms of neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like and depression/mood irritability. Specifically, we hypothesized that a neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like irritability trajectory would be defined by an early age at onset and a male preponderance and would be associated with an increased genetic liability to ADHD and ADHD diagnosis in childhood, whereas a depression/mood irritability trajectory would be defined by a later age at onset and a female preponderance and would be associated with increased genetic liability to depression and depression diagnosis in adolescence.

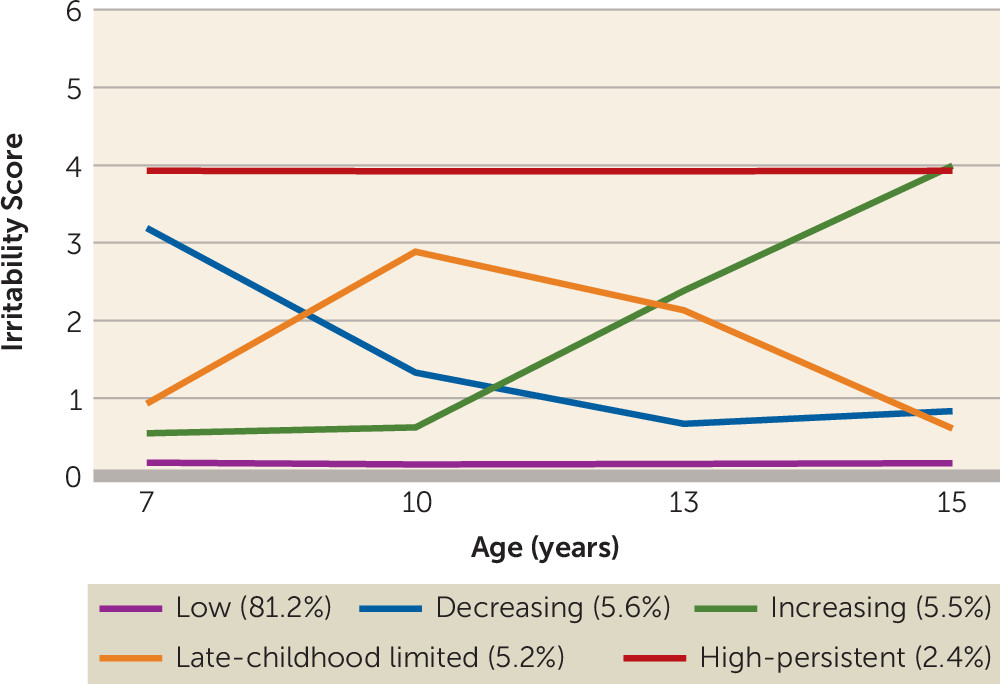

We identified five distinct developmental trajectory classes of irritability across childhood and adolescence. Four classes were characterized by elevated levels of irritability during at least some of this developmental period. Two irritability trajectory classes were early onset: one was defined by symptoms that decreased over time, and the other was defined by high symptoms that persisted (5.6% and 2.4% of the study sample, respectively). These two groups exhibited developmental patterns similar to patterns found in ADHD, with some individuals showing persistence over time and others remitting. An additional, unexpected trajectory with irritability onset in late childhood was defined by an increase in symptoms around age 10 and a subsequent decrease around age 13 (5.2% of the study sample). This is the age of high school transition in the United Kingdom, as well as the onset of puberty for many; however, we can only speculate as to the underlying mechanisms for this trajectory class, because this group has not been previously described. The final trajectory was defined by increasing symptoms with a later onset, around adolescence (5.5% of the study sample).

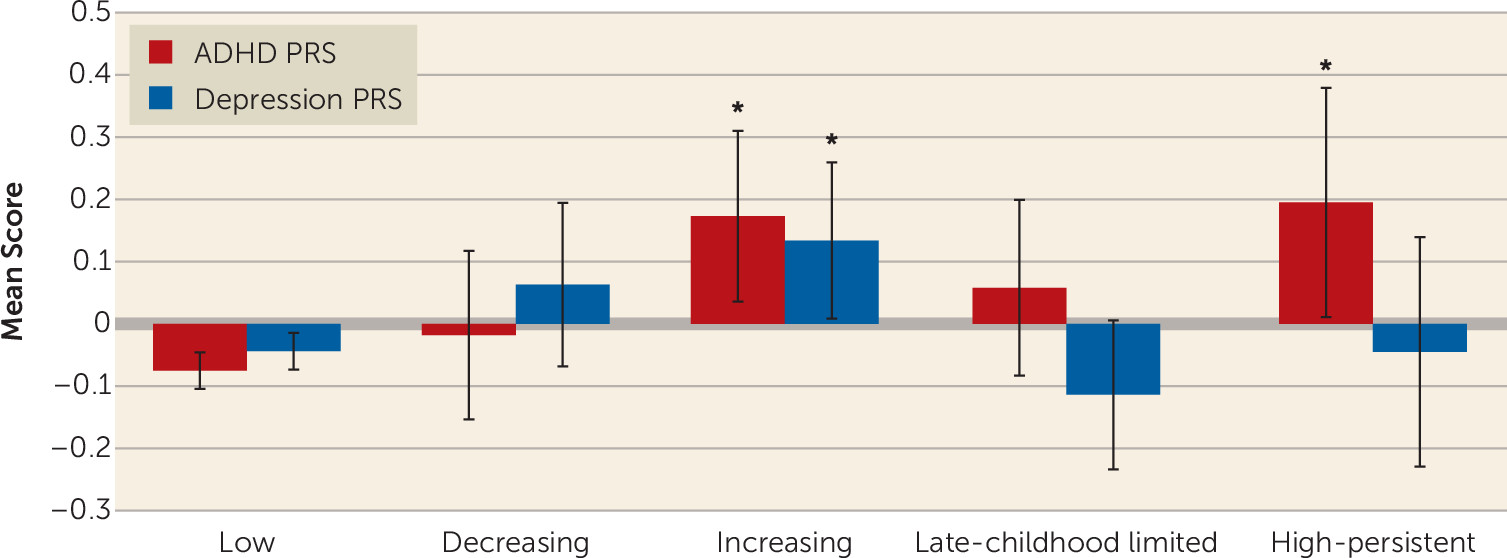

In line with our first hypothesis, the two irritability trajectories with early onset (decreasing and high persistent) were both associated with male sex and ADHD diagnosis in childhood, as was the late-childhood onset (late-childhood limited) class. The high-persistent trajectory was also associated with increased ADHD genetic risk scores, although the childhood-onset trajectories that did not have persistent symptoms (decreasing and late-childhood limited) were not. This is similar to findings on the developmental patterns of ADHD symptoms, that individuals with persistent compared with childhood-limited symptoms of ADHD have an increased genetic liability to ADHD (

27). An association between irritability and ADHD PRS has been observed previously in the total sample, as well as in a clinical sample, and accords with an earlier twin study that observed shared genetic links between ADHD and emotional lability (

11,

12). Interestingly, the later-onset (increasing) irritability trajectory was also associated with ADHD PRS, although rates of childhood ADHD diagnosis were low. It may be that the phenotypic expression of ADHD genetic liability in this predominantly female group manifests as mood problems (e.g., see reference

28), although further work would be needed to investigate this hypothesis. Our findings therefore support the suggestion of a neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like type of irritability, which has an early onset, has a male preponderance, and is associated with ADHD.

In line with our second hypothesis, the trajectory with irritability onset in adolescence (increasing trajectory class) was associated with female sex. This depression/mood type irritability trajectory class was also associated with depression genetic risk scores and depression diagnosis in adolescence. This class was also associated with ADHD genetic risk scores. Although twin studies have indicated genetic overlap between irritability and depression, previous analyses of this same sample failed to observe an association between irritability and depression genetic risk scores (

8,

29). This has raised questions about the primary classification of severe irritability as a mood problem. Indeed, it appears that ICD-11 is going to take a different approach than DSM-5 and conceptualize irritability as a specifier of oppositional defiant disorder and not include severe irritability/disruptive mood dysregulation disorder as a mood disorder (the approach taken in DSM-5). However, ICD-11 now includes irritability as an alternative symptom to depressed mood in dysthymic disorder in children and adolescents (similar to DSM-5 for depression). Our findings suggest that the association between irritability and depression genetic risk scores may be specific to a type of irritability that has an onset during adolescence.

Regardless of whether the DSM-5 or ICD-11 stance on categorizing severe irritability is most valid, neither has taken a developmental approach. Our findings suggest that development matters. This view is not new (e.g., see reference

30), and it has been applied to other phenotypes, including antisocial behavior (

31), but perhaps has been forgotten, since it poses substantial challenges to clinicians and researchers. A transdiagnostic conceptualization of irritability, such as that used in the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria or the

p-factor framework (

32), could provide a helpful research framework for conceptualizing irritability dimensionally across multiple levels. Our study suggests that if such a framework were to be implemented, it should be developmentally informed, taking into account age and age at onset.

In terms of how the trajectory classes relate to psychiatric diagnoses, the diagnostic rates reported here are relatively low, because our sample is a population-based cohort. Nevertheless, there are some notable observations. Interestingly, while the high-persistent neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like irritability trajectory class was not associated with depression PRS, individuals in this class showed a risk of adolescent depression similar to that for the increasing depression/mood irritability trajectory. Thus, both trajectory classes were associated with risk of depression in adolescence, although the mechanisms of this association are likely different. For example, increased risk for depression in the early-onset irritability type may have been driven by environmental factors, such as increased life events associated with irritability, rather than genetic risk for depression, although further research is needed. It is established that child neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD, as well as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct problems, are risk factors for later depression, so it is perhaps not surprising that the neurodevelopmental irritability trajectory was associated with depression, although emerging research suggests that the presence of irritability in individuals with ADHD confers additional risk of depression (

33).

Consistent with previous work (

2), we found elevated rates of other psychiatric disorders among individuals with elevated irritability. Rates of oppositional defiant disorder were particularly high in the elevated irritability trajectory classes and followed a developmental pattern similar to that of irritability levels. This is not surprising given that irritability is a core component of oppositional defiant disorder; indeed, irritability was defined by terms from the oppositional defiant disorder section of the Development and Well-Being Assessment. However, a large proportion (39%−99%) of individuals in the elevated irritability trajectory classes did not have oppositional defiant disorder, which suggests that irritability among individuals without oppositional defiant disorder is important and adds to the idea that irritability is transdiagnostic. Interestingly, despite previous research that found associations between irritability and anxiety as well as depression (

2), we did not find strong evidence that the rates of generalized anxiety disorder in adolescence differed between those in each of the irritability trajectory classes. Previous research on links between irritability and depression has often included anxiety symptoms in the same measure (

29) or found the same pattern of results for depression and anxiety (

6). Our findings suggest specificity to depression in adolescence.

One explanation for the apparent existence of different irritability types is that irritability is simply a feature of different underlying diagnoses (e.g., depression and ADHD). However, the low rates of these diagnoses in the population-based trajectory classes (

Tables 2 and

3) suggest that this is not the case (e.g., only a small minority of those in the increasing irritability trajectory class had a diagnosis of depression), and associations with PRSs were similar when we excluded individuals with diagnoses (see Table S7 in the

online supplement). In addition, sex differences for the high-persistent and increasing irritability trajectory classes were not as pronounced as typically reported for depression and ADHD (

34). These observations suggest that the different irritability types are not simply a feature of different underlying diagnoses (ADHD and depression).

Our findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, ALSPAC is a longitudinal birth cohort study that suffers from nonrandom attrition, and individuals with increased genetic liability to a disorder and with higher levels of psychopathology are more likely to drop out of the study (

35,

36). However, our trajectory analyses used full-information maximum likelihood estimation (

23) so that complete data on irritability were not required. Moreover, inverse probability-weighted analyses suggested that missingness of genetic data did not have a large effect on our findings. It is possible that associations between depression PRS and (increasing) irritability were inflated by some of the cases in the depression GWAS involving (adolescent-onset) irritability as a symptom. In addition, while PRSs are useful indicators of genetic liability, ADHD and depression PRSs currently explain a minority of common variant liability to the disorder (

20,

21). Our analyses were therefore underpowered to detect associations between PRS and irritability trajectories: our analyses had 80% power to detect odds ratios of 1.35 for the increasing trajectory and 1.60 for the high-persistent trajectory (

37). Thus, while the effect sizes we observed are consistent with similar types of analyses reported elsewhere (

38), PRSs should be regarded as indicators of genetic liability rather than as predictors of psychopathology. We deliberately elected to use depression PRS derived from adult samples that reflect “typical” depression. Childhood or prepubertal depression is rare and considered to be atypical not only in age at onset but also in terms of other features (e.g., see reference

39). The associations that we observed between adolescent-onset irritability and depression PRS are therefore consistent with previous work demonstrating associations between irritability and depression in adolescence and adulthood.

We did not include covariates in our analyses of ADHD and major depressive disorder diagnoses because we were interested in describing observed associations, which means that we cannot infer any causal associations between irritability and diagnosis. Different methods, such as Mendelian randomization, would be needed to investigate such research questions (

40). Finally, our aim was to use a developmental approach to investigate nosology. However, diagnostic and subgroup overlap is the rule in psychiatry, and this study was no exception. Our neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like and depression/mood irritability classes were both associated with ADHD and depression diagnoses and ADHD genetic risk scores. We observed different patterns for these classes rather than identifying completely distinct groups. Finally, there were difficulties in determining the optimum number of classes using growth mixture modeling. Given that this is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate irritability trajectories across childhood and adolescence, we emphasize that further research is needed in this area, including testing the replicability of these trajectories in different samples.

In conclusion, our study identified different developmental trajectories of irritability, including one with characteristics typical of neurodevelopmental/ADHD-like problems—early onset, male preponderance, and clinical and genetic links with ADHD—and one with characteristics typical of depression/mood problems—later onset, female preponderance, and clinical and genetic links with depression. Both groups were associated with risk of adolescent depression, and both were associated with ADHD genetic risk scores. Overall, these findings suggest that the developmental context of irritability may be important in its conceptualization, and this has implications for treatment as well as nosology (

2).