Depression commonly co-occurs with substance use disorders and contributes to poor outcomes (

1–

5), including increased substance use (

6,

7), more severe illness trajectories (

8,

9), higher rates of suicide (

3,

10–

13), fatal overdoses (

14), and overall mortality (

15). Antidepressants and psychotherapy are both effective, empirically supported treatments for depression; however, depression remains undertreated, with, on average, one-third of patients experiencing a major depressive episode receiving no treatment at all (

16,

17). To ensure guideline-concordant depression treatment, initial treatment and continuation of treatment are critical for optimizing effectiveness and mitigating these poor outcomes, especially among patients with comorbid substance use disorders (

18–

21).

Best practices support providing individuals with depression and substance use disorders treatment for both disorders (

18), with integrated or concurrent treatments to target both disorders simultaneously (

22–

26), with a focus on ensuring access to guideline-concordant treatment to optimize effectiveness and reduce the public health burden of depression. Clinical practice guidelines issued by the American College of Physicians and the U.S. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) recommend treating depression with pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy), with a combination of both in cases of severe depression (

27,

28). However, co-occurring substance use disorders present additional barriers beyond those associated with the treatment of depression broadly (

29,

30), in part as a result of inaccurate clinical beliefs about the need for abstinence to garner benefits of depression treatment (

23,

31) and provider concerns about medication interactions, among other barriers. Previous work has shown that only about half (55.4%) of individuals in the United States with co-occurring substance use disorder and depression received any depression treatment (

32).

Treatment of depression is a priority for patients with comorbid substance use disorders. However, no study to date has examined whether those with co-occurring substance use disorders and depression receive similar care to those without substance use disorders across both medication and psychotherapy-based treatment modalities or the degree to which specific substance use disorders are differentially associated with receipt of guideline-concordant depression treatment. As the largest provider of addiction treatment services in the United States, the VHA provides the opportunity to assess the quality of depression treatment between patients with and without substance use disorders, and with specific substance use disorders, across the nation.

Results

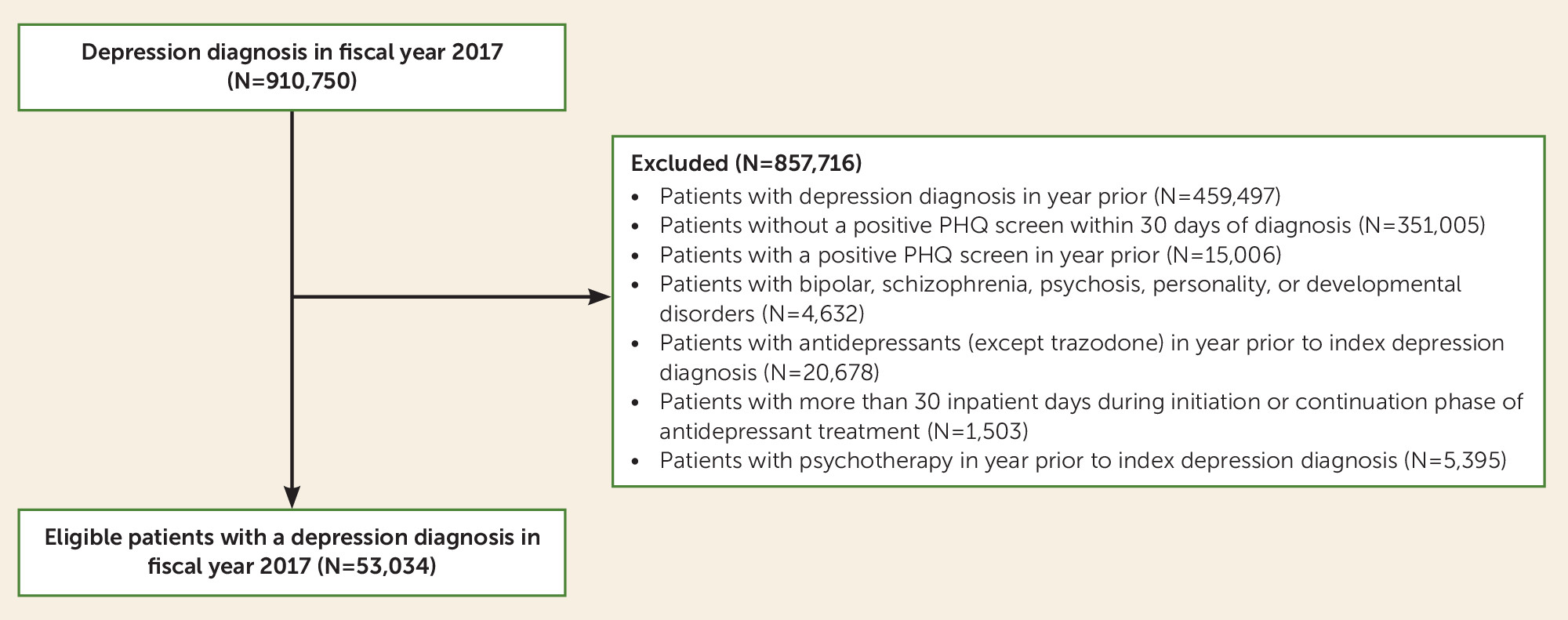

The study cohort included 53,034 patients diagnosed with a new episode of depression during fiscal year 2017; 28,081 (52.9%) of these patients received any antidepressant treatment, and 18,484 (34.9%) received any psychotherapy for depression within 90 days following their diagnosis. Of this cohort, 7,516 (14.2%) had a substance use disorder diagnosis in the year before the depressive disorder diagnosis. Despite patients with substance use disorders having more visits in mental health and primary care settings in the year following the depression diagnosis (an average of 14.1 visits [SD=18.1] compared with 10.2 visits [SD=10.9] among those without substance use disorders), providing more opportunity for depression treatment, patients with substance use disorders received less guideline-concordant depression treatment across all metrics. Observed rates without adjusting for covariates show that acute- and continuation-phase antidepressant treatment was provided to 59.4% and 36.3%, respectively, of those with co-occurring substance use disorder and depression, compared with 66.2% and 44.8%, respectively, of those without substance use disorders. With regard to psychotherapy, 31.6% and 26.8% of those with substance use disorders received acute and continuation phases of depression treatment, respectively, compared with 35.4% and 32.2% of those without substance use disorders. Among those with substance use disorders, the vast majority received most of their psychotherapy or medication-based depression treatment in mental health clinics (47.0% of psychotherapy [N=1,117], 59.1% of antidepressants [N=2,390]) or in primary care/primary care mental health integration clinics (42.7% of psychotherapy [N=1,014], 31.8% of antidepressants [N=1,287]), with only a small minority of patients receiving depression care in substance use disorder specialty clinics (3.5% of psychotherapy [N=83], 2.5% of antidepressants [N=102]) or other clinics (6.9% of psychotherapy [N=163], 6.6% of antidepressants [N=265]). Patient characteristics by substance use disorder status are summarized in

Table 1 for all covariates. In brief, patients with substance use disorders were slightly younger on average and were more likely to be male, Black, homeless, and have comorbid psychiatric conditions. Those without a comorbid substance use disorder were more likely to have a service-connected disability, have more comorbid medical conditions, and live in a rural area.

Table 2 presents the results of the multivariate logistic regression models for guideline-concordant depression treatment for patients with and without substance use disorders.

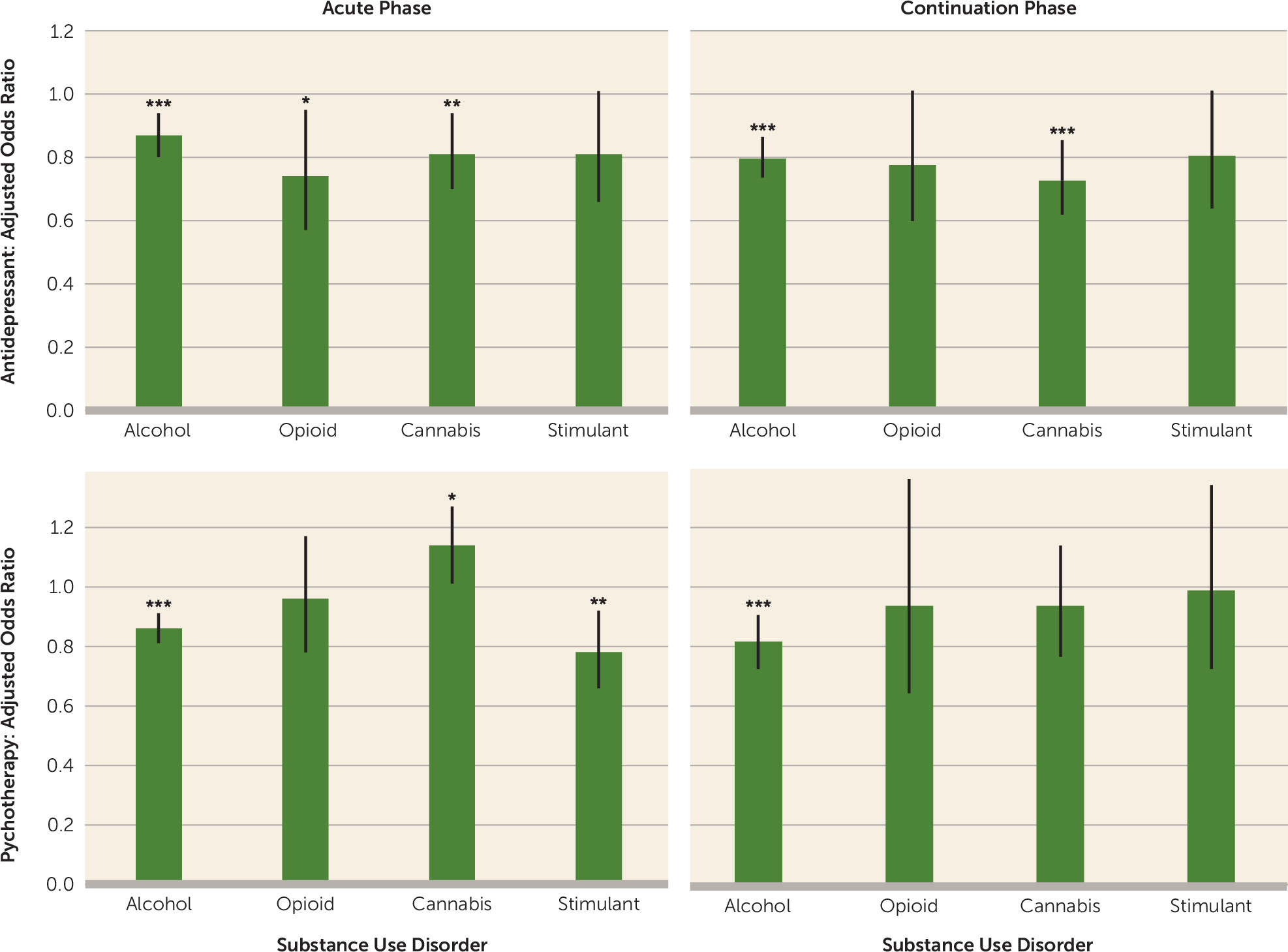

Figure 2 shows the covariate-adjusted results by specific substance use disorders (see also Table S1 in the

online supplement). Patients with substance use disorders had lower odds of receiving guideline-concordant care, including lower odds of receiving adequate acute and continuation phases of antidepressant and psychotherapy treatment (antidepressant: acute phase, adjusted odds ratio=0.79, 95% CI=0.73, 0.84, p<0.001; continuation phase, adjusted odds ratio=0.74, 95% CI=0.69, 0.79, p<0.001; psychotherapy: acute phase, adjusted odds ratio=0.87, 95% CI=0.82, 0.91, p<0.001; continuation phase, adjusted odds ratio=0.81, 95% CI=0.73, 0.89, p<0.001).

The lower odds of guideline-concordant care correspond to 21% lower odds of receiving acute antidepressant treatment, 13% lower odds of initial psychotherapy treatment, 26% lower odds of adequate continuation of antidepressants and 19% lower odds of continuation of psychotherapy. Based on the predicted probabilities of receipt of guideline-concordant depression treatment, an estimated 55% of people with comorbid substance use, compared with 61% without, received adequate acute antidepressant treatment and 27% of people with comorbid substance use disorders, compared with 29% without, received initial psychotherapy. With regard to continuation of treatment, 33% of people with comorbid substance use, compared with 40% without, received adequate continuation of antidepressants and 22% of people with substance use disorders, compared with 25% without, received adequate continuation of psychotherapy.

Lower-quality depression care was evident across multiple specific substance use disorders. Alcohol (adjusted odds ratio=0.87, 95% CI=0.80, 0.94, p<0.001), opioid (adjusted odds ratio=0.74, 95% CI=0.57, 0.95, p<0.05), and cannabis use disorders (adjusted odds ratio=0.81, 95% CI=0.70, 0.94, p<0.01) were all associated with lower odds of adequate acute-phase antidepressant treatment. Alcohol (adjusted odds ratio=0.81, 95% CI=0.75, 0.88, p<0.001) and cannabis (adjusted odds ratio=0.74, 95% CI=0.63, 0.87, p<0.001) use disorders were also associated with significantly lower odds of adequate continuation of antidepressants. Similarly, alcohol (adjusted odds ratio=0.86, 95% CI=0.81, 0.91, p<0.001), cocaine (adjusted odds ratio=0.78, 95% CI=0.66, 0.92, p<0.01), and other substance use disorders (adjusted odds ratio=0.71, 95% CI=0.56, 0.89, p<0.01) were associated with lower odds of an initial psychotherapy session for depression. Only veterans with alcohol use disorders (adjusted odds ratio=0.81, 95% CI=0.72, 0.90, p<0.001) were at lower odds of adequate continuation of psychotherapy for depression. Cannabis use disorder diagnosis was associated with slightly higher odds of psychotherapy for depression (adjusted odds ratio=1.14, 95% CI=1.01, 1.27, p<0.05). In a sensitivity analysis where psychotherapy sessions were defined broadly, regardless of the treatment target, there was no detected difference in the acute phase but lower odds of continuation of psychotherapy (adjusted odds ratio=0.89, 95% CI=0.82, 0.96, p<0.01) among patients with a substance use disorder compared with those without a substance use disorder (see Table S2 in the online supplement).

Several demographic characteristics, psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and contextual factors were also associated with lower odds of receiving guideline-concordant depression treatment (see

Table 2). In general, racial and ethnic minorities and those experiencing homelessness had lower odds of receiving guideline-concordant antidepressant treatment. Those from rural areas and those with medical comorbidities, as measured by the Elixhauser score, had higher odds of adequate antidepressant treatment. Those with additional psychiatric comorbidities (i.e., PTSD or anxiety disorders) and those who lived farther away from a health care facility had lower odds of receiving adequate psychotherapy.

Discussion

In this large national sample, we found that patients with comorbid depression and substance use disorders receive lower quality care than those with depression but without substance use disorders. After accounting for demographic, medical, psychiatric, and contextual factors, we found that patients with substance use disorders had lower odds of adequate acute-phase treatment (21% and 13% lower for antidepressant and psychotherapy, respectively) and lower odds of adequate continuation of treatment (26% and 19% lower for antidepressant and psychotherapy, respectively) for depression. Despite having higher overall health care utilization, patients with substance use disorders still received less guideline-concordant care for depression. These results are consistent with previous work showing lower rates of any depression treatment among patients with comorbid substance use disorders (

32), including less guideline-concordant antidepressant treatment (

45). By assessing both antidepressant medications and psychotherapy for depression, we found that psychotherapy does not account for the lower utilization of medication-based interventions among patients with comorbid substance use. Indeed, receipt of guideline-concordant antidepressant and psychotherapy treatments is consistently lower across depression care metrics among those with comorbid substance use disorders. Although the magnitude of difference (approximately 20% lower odds) may seem modest, both depression and substance use disorders are highly prevalent, such that even modest differences amount to large numbers of individuals. These findings highlight the opportunity for increased depression treatment across both treatment modalities for those with substance use disorders to achieve guideline-concordant care.

Increased identification of those in need of treatment through universal screenings, the establishment of clinical practice guidelines, and development of quality metrics for care have led to substantial progress in depression care (

22,

23,

33,

46). Nonetheless, depression remains vastly undertreated (

16,

46), with observed rates of guideline-concordant depression care in the present study ranging from 66.2% of patients without substance use disorders receiving adequate acute-phase antidepressant treatment to 32.2% of these patients receiving adequate continuation of psychotherapy. The unmet treatment need is even greater among those with co-occurring substance use disorders. Substance use disorders and depression affect each other bidirectionally (

47,

48) and are most effectively treated concurrently (

18,

49,

50). Meta-analytic work has shown that receipt of high-quality depression care improves depression outcomes across different substance use disorders (

23,

34). The most improvement from treating depression (i.e., the largest effects) is seen in patients with co-occurring alcohol use disorders (

23). Despite this evidence of improved outcomes with depression treatment, we found markedly lower odds of depression treatment for those with co-occurring alcohol use disorder and depression (see

Figure 2).

Inequity in guideline-concordant care is likely related to multiple factors, including both patient and structural barriers. Patients with co-occurring depression and substance use disorder often suffer from complex psychological presentations characterized by multiple symptoms, such as reduced motivation, low energy, impaired cognition, and disorganization, as well as continued use or relapse to substance use. These symptoms, in addition to experiencing stigma related to both depression and substance use disorders, can impede a patient’s ability to engage with treatment plans and can lead to lower treatment retention (

51–

53). Barriers to retention are well documented in treatments for substance use disorders (

54,

55) and may be captured in part by the lower rates of depression treatment continuation among patients with comorbid substance use disorders. As these patients may be more likely to drop out or be nonadherent with treatment, interventions are needed that target improved treatment retention and/or reduce barriers to treatment, such as telemedicine, especially for high-risk patients, such as those with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders. Of note, individuals with co-occurring depression and substance use disorders report more unmet need for mental health services than those without substance use disorders despite receiving higher rates of mental health services in general, including both psychotherapy and medication (

56). Receipt of less guideline-concordant depression treatment in those with co-occurring depression and substance use disorders may paradoxically contribute to greater mental health utilization as a result of receiving inadequate or piecemeal services that fail to achieve treatment goals, resulting in a continued need for care.

Structural barriers contribute to inequality of depression treatment for those with substance use disorders, including barriers related to the availability of depression treatment and how depression care is provided in both substance use disorder specialty and other settings (

57). Insufficient provider training in the assessment and treatment of complex presentations, such as patients with comorbid depression and substance use disorders, may contribute to inaccurate beliefs and stigmas, an inability to accurately identify co-occurring disorders (

58–

60), a lack of awareness of appropriate referral sources (

61,

62), and a lack of preparedness to treat co-occurring disorders (

63). For example, among medical residents, approximately 1 in 10 report feeling unprepared to treat patients with substance use disorder and/or depression (

63). Lack of training may lead to contraindicated treatment plans, such as stipulations that patients complete substance use disorder treatment and achieve a period of abstinence before addressing depression, limiting access to guideline-concordant depression treatment for patients with substance use disorders. Training, targeted feedback, and facilitation strategies for providers to reduce stigma, correct inaccurate beliefs, and increase awareness of best practices for co-occurring substance use disorders and depression are needed to improve the provision of depression treatment.

Institutional barriers, such as factors that systematically impair access for certain groups of patients, also contribute to disparities in depression treatment for those with substance use disorders. Organizational configuration in health care settings may be a barrier to concurrent treatment of depression and substance use disorders. Disorder-specific clinics (e.g., substance use disorder specialty clinics) can make it challenging to integrate treatment approaches. Previous work found antidepressant treatment predominantly in primary care for those with co-occurring depression and alcohol use (

58), and we find that antidepressant treatment, as well as psychotherapy, is also often provided in mental health and integrated primary care and mental health clinics.

To maximize improvements in depression care for the sizable number of patients with comorbid substance use disorders, efforts must target general mental health and integrated primary care and mental health clinics, because these settings have much more expertise in behavioral health (compared with primary care) and are where many of these patients are being seen. However, historically, clinicians in these clinics have reported a lack of comfort in addressing the needs of patients with substance use disorders without additional training (

64). One potential model for improvement is care management, which facilitates patient care with structured coordination and communication between treating providers and improves depression treatment outcomes in general (

60), with initial evidence that specifically designed collaborative care models improve outcomes for those with substance use disorders and depression (

61). Noteworthy barriers to scalable collaborative care models, particularly outside of the VHA, include insufficient reimbursement for care management services that are needed to facilitate effective treatment across disorders and specialties (

60) and ongoing concerns about the cost-effectiveness of these models. Collaborative care models identify unmet treatment needs, lead to additional service provision, and thus require large up-front costs for downstream improvements in overall health and subsequent service utilization reductions (

61). At the same time, depression-specific treatment should also be further enhanced in existing substance use specialty settings and dual-diagnosis clinics specializing in depression and substance use disorders, similar to the integrated PTSD and substance use disorder clinic model currently available in the VHA system.

Several characteristics other than co-occurring substance use disorders were also associated with quality depression treatment. Consistent with findings from previous work on initiation of depression treatment in primary care mental health integration clinics (

65), we found that patients who were younger and female had higher odds of guideline-concordant depression treatment, across medication or psychotherapy modalities. Lower odds of psychotherapy but not antidepressants were observed for patients with co-occurring psychiatric disorders and those living farther from a health care treatment setting. People living in more rural settings, farther from medical centers, may experience fewer barriers to medication-based treatments, which are frequently received from general medicine providers, than psychotherapy, which may require access to specialty mental health providers and require burdensome frequent office visits. Nearly all racial and ethnic minority groups were less likely to receive adequate medication-based treatment. This relationship was most pronounced among those identifying as Black, who were half as likely to receive guideline-concordant antidepressant treatment compared with individuals who identified as White. This pattern may be due in part to patient preference (

64,

65) but is likely compounded by less frequent assessment and less treatment of co-occurring mental health problems among marginalized groups (

59–

63).

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample is limited to veterans in care within the VHA system, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. However, the VHA is the largest single health care provider in the United States, and it offers a granular look at services rendered otherwise unavailable through any other health care data set. Second, this analysis does not include services received outside the VHA system (e.g., through a community health care setting). Third, the sample selection criteria (i.e., new depression diagnosis in fiscal year 2017 and a positive PHQ depression screen within 30 days of the diagnosis) may limit the generalizability of findings to the degree that these criteria may not capture some people with depression (e.g., preexisting diagnosis, noncompletion of depression screen). Fourth, although the indicators of adequate acute and continuation phases of care are the most often used measures of the quality of depression care, they do not encapsulate all features relevant to high-quality depression care.

In summary, our study of patients in a national health care system indicates a treatment gap in guideline-concordant depression treatment among those with substance use disorders compared with those without. Future research should focus on ways to increase delivery of empirically supported depression treatment to patients with substance use disorders, including targeted interventions for patients and clinicians and implementation of care models to reduce barriers for concurrent treatment. Together, these strategies will promote more equitable provision of medication and therapy for patients with depression, including those with substance use disorders.