Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is a neurodegenerative disorder known for alterations in socioemotional behavior. Patients with bvFTD develop apathy, disinhibition or social impropriety, compulsions or stereotypies, lack of empathy, and dietary changes along with deterioration of frontal and anterior temporal regions.

1 Many patients also develop poverty of speech with primarily decreased verbal output and fluency, and some develop nonfluent progressive aphasia.

2In the absence of poverty of speech, a subgroup of patients with bvFTD have had positive speech and language features reminiscent of psychosis and leading to the misdiagnoses of schizophrenia or mania.

3 We evaluated the speech and language of well-diagnosed patients with bvFTD, divided them into those with and without poverty of speech, and then compared them on other psychotic-like language and speech features and MRI.

Methods

Among bvFTD patients enrolled in the UCLA Behavioral Neurology Clinic, we evaluated 12 who met International Consensus Criteria for probable bvFTD with supportive frontal-anterior temporal changes on clinical MRI.

1 These patients were part of an institutional review board-approved study.

The examining clinician completed the Scale for the Assessment of Thought, Language, and Communication (TLC) from the initial presentation examinations.

4 The TLC assesses formal thought disorder based on clinical observation of 18 items rated on 0–3 or 0–4 scales, with an additional global severity rating score. The TLC has good interrater reliability.

4,5 On the initial TLC item, the bvFTD patients were divided into two groups: those with (PvSp+) and without poverty of speech (PvSp–). The groups were then compared on the remaining 17 “positive psychotic-like speech” items.

In order to compare clinical MRI scans from different scanners and institutions between the PvSp+ and PvSp– groups, we coded them with a visual inspection method.

6 The visual scale rated frontal and anterior temporal atrophy in each hemisphere on a 0- to 4-point scale from “absent” to “severe.” Prior interrater reliability for this MRI visual scale was r

s=0.42 for 72 ratings (p<0.001).

6Statistical Analysis

The PvSp+ and PvSp– groups were compared on general characteristics, TLC global and item severity scores, and MRI visual ratings using t tests (except chi-square test for sex) for low sample sizes where continuous variables test of normality (Shapiro-Wilks) permitted.

7 TLC items not normally distributed were further compared with the Mann-Whitney U statistic.

Results

General Characteristics

Among the 12 bvFTD patients (male, N=5; female, N=7), the mean age at presentation was 59.0 years [±11.6], and they had a mean of 16.1 years [±1.8] of education, with an initial mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 27.3 [±2.2]. On the TLC, all 12 bvFTD patients had symptoms (mean global severity rating score=1.0 [±0.58]), with the severity scores disclosing a division between nine patients with poverty of speech and three with no poverty of speech.

PvSp– Versus PvSp+ Comparison

There were no differences on age, gender, education, or MMSE scores. On the TLC global severity ratings, which were normally distributed for both groups (Shapiro-Wilks significance: PvSp–: 0.59 and PvSp+: 0.24), the PvSp– group had significantly worse scores (PvSp–: 1.85 [±0.08] versus PvSp+: 0.72 [±0.31], t=6.06, df=10, p=0.001).

On the 17 positive speech items of the TLC, the PvSp– group accounted for most symptoms, including 78% of all high severity scores (3 or 4) (see

Table 1). Although individual item distributions were not normally distributed on the Shapiro-Wilks test, four items had significantly worse (Mann-Whitney U at the 0.009 level) severity scores in the PvSp– group compared with the PvSp+ group: pressure of speech, tangentiality, derailment, and clanging.

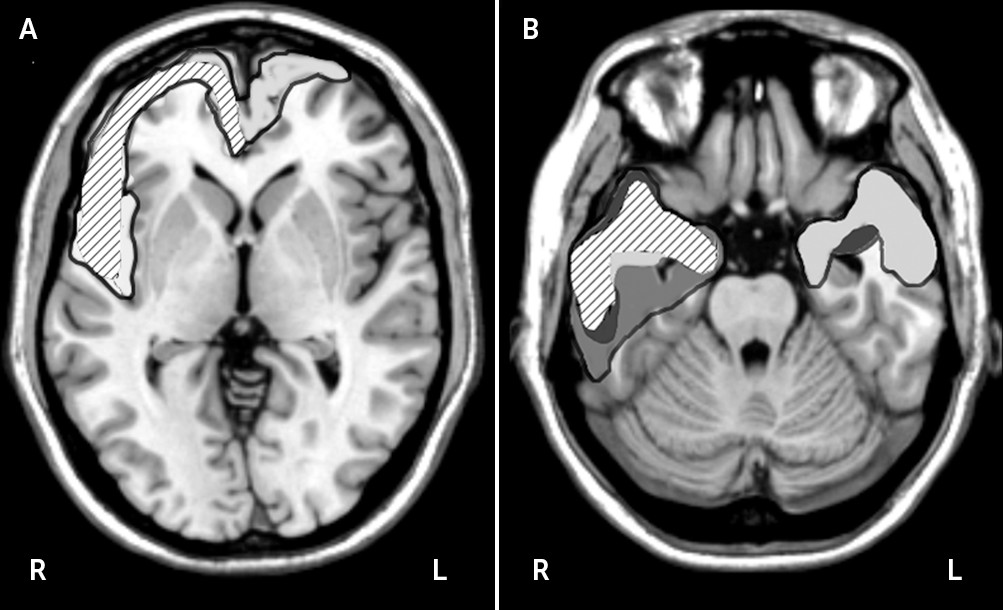

On MRI visual ratings, the PvSp– group, compared with the PvSp+ group, had greater right anterior temporal atrophy (1.56 [±0.88] versus 3.0 [±0.0]; t=−2.74, p=0.02) and less left frontal atrophy (see

Figure 1) (2.0 [±0.5] versus 1.0 [±1.0]; t=2.37, p<0.04). The PvSp– and PvSp+ groups did not differ in right frontal (2.22 [±0.67] versus 3.0 [±0.0]) and left temporal (1.33 [±1.22] versus [1.0±1.0]) atrophy.

Illustrative Case Report

A 41-year-old right-handed man with 19 years of education had a progressive change in personality characterized by incessant talking, rhyming, repeating himself, and “obsessions.” He was obsessed with eating carbohydrates, watching certain TV shows, and a number of other behaviors. He lacked insight regarding his changes in behavior. There were no delusions, hallucinations, or criteria for mania or depression. On examination, he was talkative to the point of difficulty interrupting him, and he was tangential or off-track in his commentary. He continually focused on specific words, either rhyming, clanging, or punning. For example, he continually repeated: “The Pope is a dope without hope”; and he played on the nonsense word “pog,” rhyming it with dog and log. He repeated the word “pistachio,” stating that he had a friend named Pistachio, so eating them would be cannibalism. The rest of his examination showed executive dysfunction and right frontotemporal atrophy on MRI, most prominent in the right anterior temporal lobe, with sparing of the left frontal lobe.

Discussion

Although patients with bvFTD often have poverty of speech, there are few reports of positive speech and language features typically associated with schizophrenia or mania.

3 Yet, 25% of our sample of bvFTD patients presented with absent poverty of speech and positive features on the TLC scale in the absence of delusions, hallucinations, or other psychotic or manic features.

4 In these patients, the speech and language features were not psychotic in nature, but rather reflected underlying frontotemporal behavioral disturbances. Neuroimaging indicated right-sided frontotemporal involvement, with prominent right anterior temporal atrophy and relative sparing of left hemisphere frontal language areas.

Our PvSp– bvFTD subgroup had significant severity scores for pressure of speech, tangentiality, derailment, and clanging. The pressure of speech was difficult to interrupt, and although not accompanied by other manic symptoms, it cannot be entirely distinguished from secondary mania associated with right hemisphere disease. They were also tangential in response to questions, a process often seen in right frontal disease,

8 and had “derailment,” a related process in which they go off on their own with loosely related or totally unrelated commentary. Finally, they had significant clanging, where they would repeat words and their associations based upon the word sounds. Clinicians often associate clanging with the disorganized speech of schizophrenia.

4,5,9 Possibly as part of an overall fixation with word sounds, the PvSp– bvFTD patients also had punning, or the humorous use of words to suggest two or more of its meanings or similarly sounding words.

10These changes are localized to injury in the right frontal and anterior temporal regions. First, right frontal disease can result in tangentiality with digressions, rambling, and free association of ideas to the point of confabulation.

3,8,11 Patients with right predominant bvFTD may also have a tendency toward childish humor and compulsive punning.

10,12 Second, sparing of the left frontal and left temporal areas, including regions of language and rhyme judgments, may be critical to releasing positive language and speech symptoms. Recent functional MRI evidence, for example, indicates that rhyme judgment tasks involve the left inferior frontal cortex.

13 Third, right anterior temporal lobe atrophy contributes to word sounds preoccupation in these patients. BvFTD with medial temporal disease but spared lateral temporal areas in the language-dominant hemisphere may result in compulsions for wordplay, poetry, rhyming, and punning, similar to other compulsive-like behaviors that occur in this disorder.

14 In summary, right frontotemporal hypofunction could lead to left frontotemporal disinhibition with enhanced rhythm appreciation and release of rhyming abilities.

15There are limitations to this report that make the findings preliminary. The TLC comparison was not blinded and involved a limited number of patients. Nevertheless, it does disclose a subgroup of three bvFTD patients who are distinct in their psychosis-like speech and language characteristics. In addition, the attempt to localize differences on MRI images was hampered by the different origins of their clinical MRI scans. The findings, however, are highly suggestive of differences to be explored in future studies.

In conclusion, a subgroup of bvFTD patients with prominent right temporal atrophy and sparing of the left frontal lobe develop pressure of speech, tangentiality, and derailment, as well as clanging, rhyming, and punning from a fixation on the sounds of words. This preliminary study recommends a prospective, blinding evaluation of positive psychotic-like speech and language features among patients with bvFTD.