Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and their potential for long-term sequelae have garnered significant public attention in the past decade, particularly within active duty military and veteran populations (

1–

3). Data published by the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) estimate that at least 379,519 service members sustained a TBI between 2000 and 2018, of which more than 80% were classified as mild (

4). Patients with TBI, including mild TBI, often experience persistent somatic, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, including headaches, dizziness, cognitive impairment, sensory deficits, anxiety, irritability, and depression (

5–

11). Although estimates of symptom prevalence differ, one study found that at least 53% of patients with TBI reported three or more symptoms 1 year after injury (

9).

However, the concept of postconcussion syndrome (PCS), as these persistent symptoms are termed, remains controversial because of the subjective nature of diagnosis and the potential for misdiagnosis (

12). PCS lacks specificity and overlaps heavily with various psychiatric disorders (

13–

15). In many cases, PCS is clinically indistinguishable from conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder. This is especially true in military patients, given the high coprevalence of TBI, PTSD, and depression in this population (

3,

14,

16). Indeed, research has demonstrated that the presence of PTSD in combat veterans is much more predictive of the presence and severity of PCS than the actual brain injury itself (

14–

20). The controversial nature of PCS as a diagnosis has led researchers to advocate for the more inclusive term of “posttraumatic symptoms” to describe all persistent symptoms after a TBI, accounting for the multiple contributing neurologic and psychiatric etiologies (

21). This is important, given that inadequate treatment of PTSD and major depressive disorder appears to worsen outcomes for TBI (

22). Conversely, the presence of TBI appears to complicate treatment of PTSD and major depressive disorder (

23).

Other important factors contributing to the persistence of posttraumatic symptoms after a TBI are the attributions of symptoms and expectations about recovery (

24–

26). Multiple studies have suggested that patients misattribute many incidental or unrelated symptoms to their TBI, resulting in overall higher burden of symptoms (

24,

25). Such patients may be less likely to address underlying mental health needs and thus less likely to recover. However, a recent study by Hardy et al. (

27), which examined military service members with mild TBI, found that many of these patients appeared to recognize the contribution of mental health conditions, such as PTSD and depression, to their posttraumatic symptoms. To our knowledge, no other prior research has specifically examined patient attribution of posttraumatic symptoms to conditions other than TBI, such as PTSD or depression, and how patient attribution may be associated with the severity of symptom reporting.

The purpose of this study was to further explore the degree to which patients with a history of TBI attribute posttraumatic symptoms to their TBI versus PTSD or to other etiologies. We also examined how this attribution is associated with the severity of symptoms reported across various symptom domains (cognitive, affective, somatosensory, and vestibular). We examined the factors associated with the differences in attribution of symptoms to either TBI, PTSD, or both. We hypothesized that patients who attribute their symptoms to TBI have a different symptom profile from those who attribute their symptoms to PTSD. The findings of this research will assist in understanding the complex experiences of those with posttraumatic symptoms and help guide care for such patients.

Methods

Participants

This retrospective study analyzed data collected between July 2014 and June 2017 by the DVBIC site at Brooke Army Medical Center. The study included active duty service members stationed in the area who screened positive for a history of TBI. DVBIC recruited participants from primary and specialty care clinics as well as health screening fairs. A DVBIC research assistant confirmed the TBI diagnosis by using chart review and patient interview. TBIs were further classified as mild, moderate, or severe according to Department of Defense criteria—based on the estimated duration of loss or alteration of consciousness and abnormalities on neuroimaging (

2). The vast majority of the TBIs were mild, which is defined as a loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes, alteration of consciousness or posttraumatic amnesia for less than 24 hours, and a lack of structural abnormalities on brain imaging. Because of the small number of moderate or severe TBIs in the sample and the significant clinical heterogeneity that exists across TBI severity, we limited this study to participants with mild TBIs. The 59th Medical Wing Institutional Review Board provided approval prior to study initiation.

Measures

We collected basic demographic and military-specific data for study participants, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, branch of service, and military rank. Details collected about the index TBI included length of time since injury, whether the injury occurred during combat, and whether the participant was awaiting a medical discharge from the military. Medical discharge was of particular interest, given that service members who are eligible for disability based on certain injuries or diagnoses (e.g., TBI) may report or attribute their symptoms differently, compared with those who are not undergoing medical discharge from the military. Finally, we assessed the presence of PTSD (ICD-10-CM code F43.1) or major depressive disorder (ICD-10-CM codes F32* and F33*) on the basis of reviews of the service members’ medical records.

We used the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory (NSI) to evaluate the severity of posttraumatic symptoms. The NSI is a 22-item patient questionnaire that records the severity of various somatic, sensory, vestibular, cognitive, and affective complaints commonly associated with mild TBI; it has been well validated in active duty and veteran populations (

5,

28,

29). Given the inherent subjectivity of the NSI and the degree of overlap of TBI with other psychiatric and neurologic conditions, various studies have sought to derive factor structure models that provide greater specificity for TBI-related symptoms and discrimination among clinical subgroups (

29,

30).The four-factor model utilized in this study has been shown to have the best overall model fit (

29). The four factors include vestibular, cognitive, somatosensory, and affective symptom clusters. Vestibular symptoms include dizziness and balance-coordination problems; somatosensory symptoms include blurry vision, numbness-tingling, photo- or phonophobia, and dysgeusia; cognitive symptoms include forgetfulness, slowed processing, and difficulty making decisions; and affective symptoms include fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, depression, irritability, and poor frustration tolerance.

An additional brief survey, designed for this study, evaluated the degree to which study participants attributed posttraumatic symptoms to their TBI versus other clinical etiologies. The survey asked, “Considering your current symptoms, how much do you think that they are due to each of the following: TBI, pain, lack of sleep, PTSD, depression, deployment-related stress, or readjustment stress?” Responses followed a Likert scale: 0, not at all; 1, somewhat; 2, moderately; 3, very much; or 4, completely. Responses were not mutually exclusive; participants could attribute symptoms very much or completely in more than one category. To differentiate participants who attributed symptoms predominantly to TBI over PTSD, predominantly to PTSD over TBI, or both TBI and PTSD together, we developed new variables in the following manner: Those who scored TBI at least 2 points above PTSD on the Likert attribution scale were designated as TBI-predominant attribution. Those who scored PTSD at least 2 points above TBI were designated as PTSD-predominant attribution. Those who scored both TBI and PTSD as at least a 2 (moderately) were designated as combined TBI-PTSD attribution.

Statistical Analysis

We performed descriptive statistics for all demographic, military, and injury-related variables listed above. We calculated means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each attribution category. We also calculated mean total NSI score, four subscale scores, and individual item scores for the TBI-predominant, PTSD-predominant, and combined TBI-PTSD attribution groups. We statistically compared means across groups with two-tailed analysis of variance. We used logistic regression analysis to determine the relative contribution of vestibular, somatic, cognitive, and affective symptoms to the likelihood that participants attributed symptoms to TBI, PTSD, or both. Attribution was selected as the outcome variable on the basis of the a priori assumption that the symptoms patients experience influence the attribution of those symptoms. The regressions were adjusted for age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, pending medical discharge, time since injury, the presence of a PTSD diagnosis, and whether the TBI was sustained during military combat—all factors that may theoretically affect both symptoms and attribution. Odds ratios, Z scores, p values, and 95% confidence intervals were reported for each variable in the regression.

Results

Population Characteristics

A total of 372 active duty service members were included in the study.

Table 1 summarizes data on characteristics of the sample. The mean age was 36.3 years (SD=7.9), and the mean years of service was 14.4 (SD=7.1). The vast majority were male (86.8%), white (80.1%), and in the Army (91.4%). A significant proportion (78.2%) had education or vocational training beyond high school, and 19.9% were officers. The mean time elapsed since the index TBI was >4 years (55.5 months, SD=50.3. Forty-two percent of TBIs reportedly occurred during military combat. Twenty-five percent of participants were awaiting possible medical discharge from the military. Psychiatric comorbidity in this population was quite high, with 42.7% of service members currently diagnosed as having PTSD and 32.3% as having depression.

Symptom Attribution

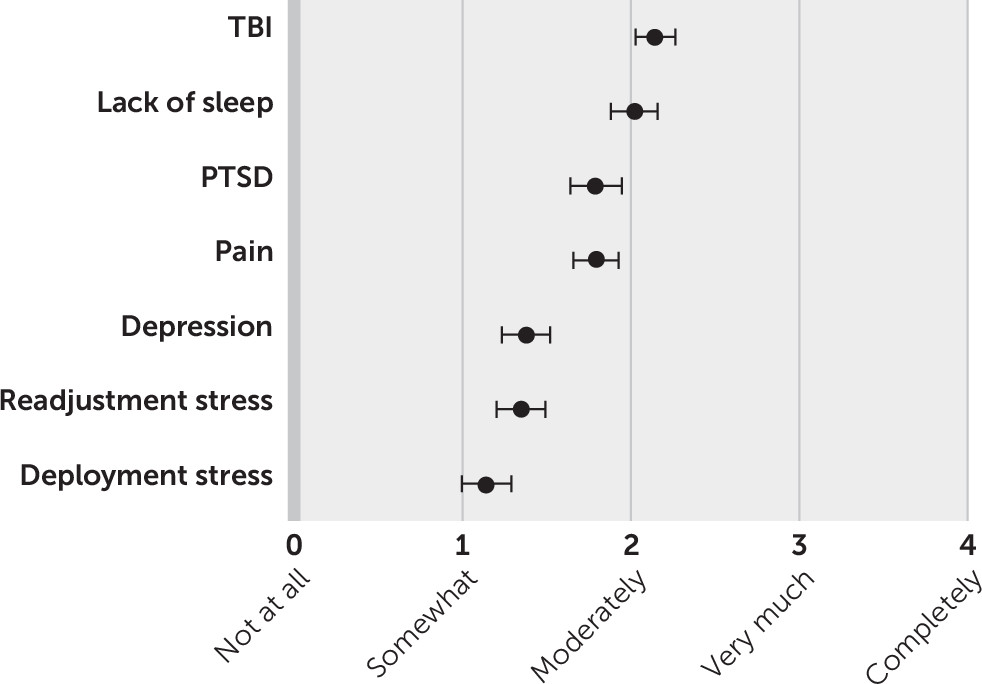

The mean level of symptom attribution to TBI and each of the other six categories is presented in

Figure 1. On average, participants attributed their posttraumatic symptoms more strongly to TBI (mean=2.15, SD=1.16) than to any other category, with most attributing their symptoms at least moderately to TBI. Lack of sleep was the second highest category (mean=2.02, SD=1.37), followed by PTSD (mean=1.79, SD=1.51), pain (mean=1.79, SD=1.32), depression (mean=1.38, SD=1.41), readjustment stress (mean=1.35, SD=1.43), and deployment stress (mean=1.14, SD=1.15).

The mean scores for each of the individual symptom items in the NSI, as well as the total subscale score and overall total NSI score, are presented in

Table 2. Fourteen of the 372 study participants are not included in this analysis due to missing data. NSI scores are stratified by how participants attributed their symptoms (TBI predominant, PTSD predominant, combined TBI-PTSD, or neither). Mean total NSI scores, symptom subscale scores, and each individual symptom score differed significantly across all attribution categories (all p values <0.01). Compared with TBI attribution, PTSD attribution was associated with higher mean symptom scores. Combined TBI-PTSD attribution was associated with the highest mean symptom scores across all categories.

The results of the logistic regression analysis are summarized in

Table 3. The results indicate that more severe affective symptoms were associated with decreased odds of TBI-predominant attribution (odds ratio=0.90, 95% CI=0.83–0.97) but increased odds of PTSD-predominant attribution (odds ratio=1.14, 95% CI=1.03–1.26) and combined attribution (odds ratio=1.09, 95% CI=1.00–1.18). In other words, for each additional point on the NSI affective subscale, the odds of attributing symptoms to TBI rather than PTSD dropped approximately 10%, whereas the odds of attributing symptoms to PTSD rather than TBI increased 14% and the odds of attributing symptoms to both TBI and PTSD increased 9%. Higher somatosensory symptoms were associated with increased odds of attributing to both TBI and PTSD (odds ratio=1.11, 95% CI=1.02–1.20). The odds ratios for cognitive and vestibular symptoms were not statistically significant. Among the other variables included in the model, a diagnosis of PTSD was associated with much lower odds of TBI-predominant attribution (odds ratio=0.20, 95% CI=0.09–0.43) and much higher odds of PTSD-predominant attribution (odds ratio=2.44, 95% CI=1.07–5.58). No other variables were statistically significant.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that service members with a history of mild TBI often attributed their persistent symptoms to conditions other than their brain injury. In addition, this finding suggests a clear association between the severity of posttraumatic symptoms across symptom categories and the degree to which patients attribute those symptoms to TBI versus PTSD.

After the analysis controlled for other contributing factors, service members who had been diagnosed as having PTSD were more likely to attribute posttraumatic symptoms to PTSD rather than to TBI. Those who reported more severe affective symptoms were less likely to attribute these symptoms to TBI alone and more likely to attribute them to PTSD.

Of interest, vestibular and somatosensory symptoms, which seem the most specific for TBI and least likely to overlap with PTSD, were not predictive of attribution to TBI over PTSD. Service members who reported higher somatosensory symptoms were more likely to attribute symptoms to both TBI and PTSD. In fact, a higher burden of symptoms across all categories was associated with a higher likelihood of attributing symptoms to both TBI and PTSD.

Another interesting finding is the fact that lack of sleep figured so prominently in patient attribution of posttraumatic symptoms. Both TBI and PTSD commonly lead to chronic insomnia and other sleep disorders. In addition, poor sleep can independently contribute to many of the vestibular, somatosensory, cognitive, and affective symptoms that are measured by the NSI (

31,

32). Thus lack of sleep in this patient population potentially represents an underaddressed clinical need that warrants additional study and intervention.

Because this study was cross-sectional and observational, it was unable to prove a causal pathway across diagnoses, symptom severity, and symptom attribution. We designed the logistic regressions with attribution as the outcome, suggesting that symptoms predict attribution. However, it also conceivable that attribution predicts symptoms, as some studies have suggested (

24,

25). In other words, patients may experience or report different symptoms based on their attributions of those symptoms to TBI or PTSD. This relationship between symptoms and attribution is likely bidirectional, as well as mediated by other factors not accounted for in this study, such as underlying patient beliefs, resilience, and distress tolerance.

This study supports existing literature demonstrating the strong overlap of symptoms between mild TBI and PTSD. The study is unique in that it focused specifically on patient attribution of symptoms. Patient beliefs and expectations about their health conditions play a vital role both in the type of health care patients seek out and in their recovery from those conditions, which may be particularly true in the case of co-occurring TBI and PTSD. Those who attribute symptoms only to their brain injury may be less likely to seek out mental health care to address these symptoms, whereas those who believe the symptoms are a result of PTSD may be more likely to engage in mental health care (

33). Thus service members with PCS could be much better served by recognition and treatment of psychiatric comorbidities. More research is needed to determine whether attribution does, in fact, determine the types of health care services patients with TBI seek out and whether attribution also influences recovery.

This study had a few key limitations. First, it examined only military service members with mild TBI, many of whom were several months or years out from their injury. Thus the study may not be very representative of other TBI patient populations, such as concussed athletes or those with more severe TBIs. Second, the results are based largely on subjective, patient-reported data and must be interpreted as such. Results may vary across patients because of differences in individual interpretation of the questions and rating scales. The NSI is an inherently subjective method for measuring the severity of posttraumatic symptoms and has relatively poor specificity for TBI, causing some to argue for more objective methods of measurement (

34). Nevertheless, the NSI was well suited for this study because it is focuses on patient-reported symptoms. Third, the data presented are cross-sectional rather than longitudinal, as discussed above. We were unable to track the evolution of symptoms or attribution of symptoms, which may have provided additional useful information. Further research can examine how attribution changes over time as certain symptoms persist or how attribution to TBI versus PTSD influences the type of health care resources sought and the timeline of recovery.

Conclusions

Persistent cognitive, somatic, and neuropsychiatric symptoms following a mild TBI are a complex phenomenon heavily influenced by psychiatric comorbidity and patient expectations. The degree to which patients believe their symptoms are a result of TBI versus PTSD was found to be associated not only with the severity of the symptoms but also with the type of symptoms reported. By better understanding patients’ experiences and beliefs regarding posttraumatic symptoms, we can provide more effective and compassionate care.