Veterans in the United States experience homelessness at a rate disproportionate to the civilian population, with an estimated 62,619 veterans homeless in 2012 (

1). Homelessness is associated with health vulnerabilities as well as with unmet need for medical and social services (

2–

5). In 2009, President Obama and the Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) set the ambitious goal to end veteran homelessness by 2015 (

6).

A primary tool in the effort to end veteran homelessness is the VA’s supportive housing (VASH) program, which provides permanent rental vouchers and case management services to homeless veterans in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The HUD-VASH program has expanded dramatically in terms of the number of vouchers available (approximately 37,000 in October 2011, growing to nearly 57,000 by August 2013), hiring of new staff, and allocation of additional resources. Data suggest HUD-VASH has been effective in housing a range of veterans, including those with co-occurring mental illness and alcohol or drug misuse (

7,

8).

In addition to increasing resources, over the past three years the VA has progressively shifted toward a Housing First (HF) approach to its HUD-VASH program, pivoting away from the traditional linear approach (often termed “treatment first”), which emphasizes an individual’s housing readiness before receipt of rental vouchers (

9). HF instead prioritizes the most vulnerable individuals for rapid placement into permanent supportive housing with no expectations regarding sobriety or treatment participation (

10). Empirical evidence for HF is mostly favorable with regard to housing stability and satisfaction but mixed for clinical outcomes and total service costs (

11–

17).

Although many clinical outcomes associated with HF have been examined, there has been limited consideration of the practical challenges associated with HF (for example, coordination with public housing authorities). Such challenges are outside the scope of traditional social services and clinical practice and may be particularly difficult to address in large-scale organizations not originally designed to implement this intensive approach to housing. Although the VA’s transition represents the largest HF implementation effort to date, endorsement and adoption of HF across organizational settings—including the National Alliance to End Homelessness (

18), the U.S. Conference of Mayors (

19), and the Mental Health Commission of Canada (

20,

21)—makes it essential that the practical realities of implementing HF be carefully articulated.

This qualitative interview study explored the challenges faced by the VA as it dramatically expands HUD-VASH and reorients to an HF approach. Throughout 2012, our team conducted 95 interviews with individuals at eight VA facilities to explore how personnel at all levels of the organization (frontline, middle-management, and leadership personnel) are experiencing the transition to HF. VA’s shift toward HF as the guiding HUD-VASH approach unfolded progressively over the period of 2009–2012, beginning with its invocation by the Secretary of the VA in 2009 (

6), alterations to the VA HUD-VASH manual in 2011 (

22), the requirement of HF-related performance metrics in late 2011, followed by a formal directive reaffirming HF as the operational approach for all HUD-VASH programs in late 2012 (

23). Using a phenomenological approach, we addressed the following broad questions: How do frontline staff respond to the challenges associated with the transition to HF? How do facility leadership understand these challenges and use their leadership position and skills to address them? How do midlevel managers communicate program goals to both frontline staff and facility leadership?

Methods

Sample

We selected a purposive sample of eight VA facilities (medical centers or health care systems). In each of four geographic regions (Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, South, Midwest, and West), two facilities were chosen that were roughly matched in terms of the number of homeless individuals in the local community (

24), the number of HUD-VASH vouchers allocated to the facility, and the demographic characteristics of patients in each facility’s Health Care for Homeless Veterans (HCHV) programs (

25).

After approval from each facility director, a list of prespecified positions (for example, case manager and HCHV coordinator) was used to identify potential interviewees. This list was adjusted by each facility to reflect the structure of its homeless program. At each facility, we conducted interviews with leadership, midlevel managers, and frontline staff between February and December 2012. A total of 95 individuals were interviewed in person.

Table 1 provides a general description of each facility and the number of interviews conducted at each.

Table 2 summarizes key characteristics of the programs. Study participation was voluntary and confidential, and all invited participants agreed to an interview except for one facility leader whose schedule could not accommodate ours. All procedures were approved by VA’s Central Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

We developed a semistructured qualitative interview protocol to assess how HUD-VASH programs are managed at each facility and the influence of organizational factors in advancing the VA goal of ending veteran homelessness through intensified efforts to provide permanent housing. To obtain a variety of perspectives on each topic, the interview guide was structured into subsections targeted to multiple roles within the organization. [The interview guide is presented in an online

data supplement to this article.] Questions regarding recent modifications to the HUD-VASH program, especially progress toward the rapid provision of permanent supportive housing, were based on core elements of HF developed through two expert panels conducted in an earlier phase of the study (including both HF originators and a combination of VA and non-VA experts), a consultation and visit with a leading HF program, and careful review of the literature (

10,

11). Because sites were at varying stages of HF adoption during the course of the study, we intentionally did not mention HF in our questions to allow current, local understandings of the program to emerge and to avoid social desirability bias. However, the interview structure honed tightly to the core elements outlined above (prioritization of the most vulnerable, rapid placement, and so forth). Questions regarding organizational aspects were based on the organizational transformation model developed at the VA’s Center for Organization, Leadership and Management Research (

26,

27). This model posits that major shifts in policy and practice require organizational engagement at all levels and explicit support from leadership to be successful.

Each interview was conducted by one of the team members, and other team members posed follow-up questions. All are experienced qualitative interviewers. Multiple team members took detailed notes, capturing responses using exact quotes whenever possible. Notes were cleaned to remove identifying references to individuals, facilities, and locations and verified for accuracy. To maximize confidentiality for VA employees speaking about potentially sensitive aspects of their work environment, interviews were not audio-recorded.

Analysis

An analysis document was created that paralleled the interview protocol. Immediately after each site visit, one team member wrote a structured narrative detailing the site’s HUD-VASH program (for example, caseloads and procedures for identifying rental units) and organizational aspects related to the expansion of rapid permanent supportive housing (for example, leadership support and availability of resources). Using the constant comparative method to analyze these narratives and the detailed notes, the team identified common practical and organizational issues in the expansion and reorientation of the HUD-VASH programs that we studied (

28,

29). When possible, direct quotes were abstracted from the notes to illustrate the issues we identified.

Results

In an effort to meet the goal of ending homelessness among veterans in a relatively brief period, the VA has progressively reoriented the HUD-VASH program to emphasize the core principles of the HF approach. The practical challenges of managing the expanded number of vouchers while adopting these principles fell heavily on frontline staff.

Frontline perspectives

Rapid placement in housing.

Because a central goal of HF is to move individuals into housing rapidly, the VA has emphasized minimizing time to placement. We found that rapid placement is challenging because of numerous factors outside the direct control of frontline staff or even facility leadership.

Local geography.

There was wide variation in the size of the catchment areas for which VA facilities in this study were responsible. Some included urban city centers and distant rural communities in catchment areas that cover hundreds of square miles, necessitating specialized knowledge of housing geography as well as time and resources for travel. Some facilities addressed this issue by assigning or permanently stationing individuals or teams in each area to ensure adequate support anywhere veterans choose to live within the catchment area.

Variations in rental markets.

Rental markets vary in terms of the availability, desirability, and safety of affordable housing, and competition for housing was often a major impediment to rapid placements. In some areas, frontline staff spoke of apartments routinely being rented within an hour of public advertisement. Programs that had previously relied on simply providing a list of suitable properties or landlords found they had to take a more active role to ensure rapid placement of veterans. This included cultivating relationships with landlords committed to housing veterans, holding public housing fairs, and actively maintaining a property list. In some areas, staff or peer specialists trained veterans in the social skills needed to negotiate with landlords to secure a lease.

Coordination with local public housing authorities.

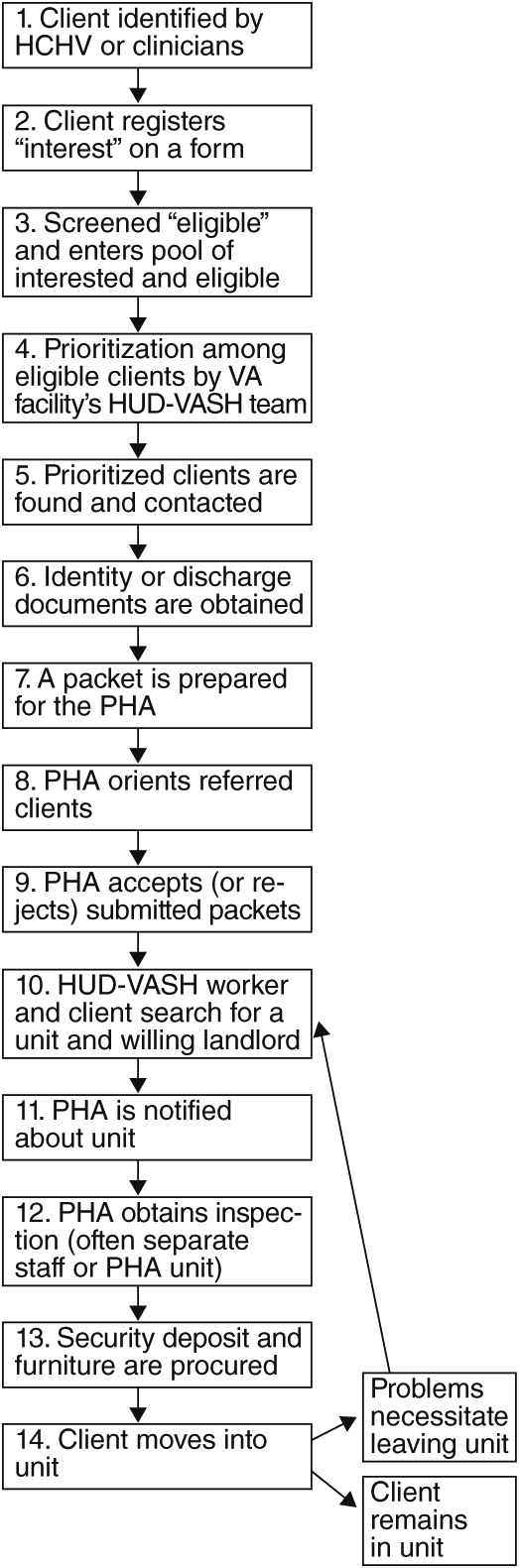

Although VA facilities identify potential HUD-VASH clients, local public housing authorities (PHAs) approve applications and administer vouchers. Housing a veteran therefore entails a lengthy set of steps in collaboration with the PHA, including securing identification documents, negotiating rental contracts, and obtaining inspection for the apartment (

Figure 1). The speed and flexibility of PHAs varied widely, although VA facilities and local PHAs reported efforts—such as the designation of specific representatives from each side and formal activities to improve processes—to streamline procedures and reduce time to placement in housing.

Availability of move-in funds.

Security and utility deposits, first month’s rent, and payment of past-due rent and utilities represent a major impediment to rapid placement in housing, because many publically funded organizations (including the VA) are legally restricted from providing direct funds to clients. In some communities we observed, private charities or VA-funded Supportive Services for Veteran Families grant awardees assist with these expenses. The availability of these funding sources is highly variable, and most offer only time-limited support. Solving this challenge demands resourcefulness of case managers. As one case manager said, “I think the VA is expecting us to be creative and make up for the deficit of them [veterans] not having income.”

Supporting highly vulnerable veterans

A second key component in the VA’s shift toward HF is the prioritization of the most vulnerable veterans for housing vouchers, tracked by VA leadership as the proportion of veterans in the program who qualify as chronically homeless. This new emphasis on housing highly vulnerable veterans has resulted in several tensions for frontline staff.

Balancing housing and case management.

Case managers (typically licensed clinical social workers) reported spending a majority of their time on housing logistics (apartment searches and cultivating relationships with landlords), often at the expense of time spent on clinical support. Many case managers expressed concern that despite success in placing veterans in housing, their ability to provide the long-term therapeutic support necessary to sustain housing was extremely limited, a finding reported in other studies of the HUD-VASH program (

30). One case manager admitted, “I have had as many as 99 messages on my phone, and I just had to delete them because they were so old. I have caught up right now.”

Several programs reported burnout and turnover of case managers unable to balance these competing demands, and some staff expressed concerns regarding professional liability because of the limited time they could spend with each veteran.

Philosophical tension between harm reduction and HF.

Although not explicit VA policy, many (but not all) frontline staff reported adopting a harm reduction perspective on assisting veterans with substance use and mental health issues (

31). Harm reduction prioritizes client goals and emphasizes willingness to work with individuals “where they are at.” Harm reduction and HF can conflict when veterans accept help but claim not to want permanent housing. Some case managers reported feeling conflicted by their belief that housing is crucial while seeking to honor veterans’ personal goals. As one said, “The Secretary said HF, and that’s harm reduction. I would say that 5% to 7% of guys don’t want to live in housing. . . . (They) . . . want to live off the grid. There can be conflict between HF and harm reduction.”

This tension was exacerbated by emphasis on one metric of success, the number of veterans housed. One case manager thus described the tradeoff between client wishes and optimizing measured performance: “We do believe that we know best—that they [veterans] should be housed. You have to listen—[but] they should never be enrolled in HUD-VASH to count against your numbers.”

No preconditions for housing.

A central tenet of the HF philosophy is a willingness to accept individuals into housing without preconditions. Neither sobriety nor acceptance of treatment for mental health or substance use issues is required, although ongoing support is provided for veterans if and when they decide they want such help. This policy shift requires a change in how veterans are sheltered before an apartment is secured, which may require weeks to months. The dilemma for programs adhering to the “no preconditions” standard is that traditional community shelter providers operate within an enforced recovery framework, requiring sobriety and participation in self-help groups. As one HCHV coordinator explained, however, it is possible to use the VA’s contracting power to encourage low-demand sheltering options: “They usually end up in our emergency housing programs. Most shelters are also using a harm reduction model. I do the contracting, and I select places that don’t kick people out because of substance use. I’m enforcing this because the contractors want VA money.”

Leadership and midlevel management

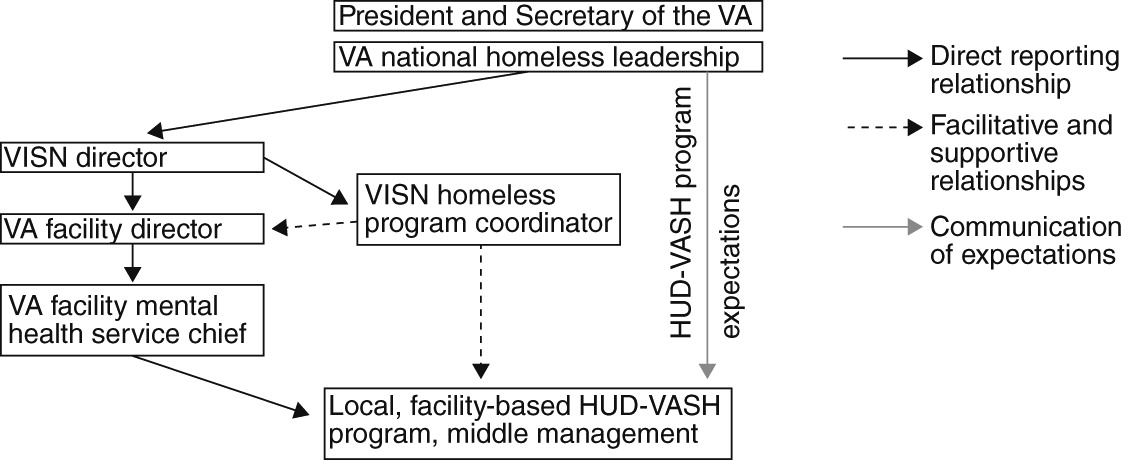

The massive expansion of HUD-VASH is directed by VA’s national leadership but is executed by VA facilities in conjunction with local public housing authorities. Actual implementation depends on management by VA facility leaders and, crucially, the midlevel managers who report to them (

Figure 2). Although facility leaders showed awareness of the dramatic expansion of HUD-VASH, their understanding of the practical challenges of executing HF was limited. In four key ways, however, involvement of facility leaders appeared to positively influence the transition to HF.

Impetus.

The VA facility leaders we interviewed strongly endorsed the national goal of ending homelessness among veterans. Many senior leaders actively worked to build staff engagement in housing placement goals and program reorientation through ongoing communications (for example, town meetings, newsletters, and daily messaging) and the inclusion of leaders of homeless programs in regular meetings of medical center service leaders. Although understanding of the practical challenges associated with HF was limited among most facility leaders (due in part to the number of competing demands on their attention), the publicly visible commitment of facility leadership to ending veteran homelessness helped to overcome various bottlenecks in the housing process, particularly the interface between VA and other government and community agencies.

Resources.

The rapid influx of HUD-VASH vouchers necessitated considerable deployment of resources in support of the program, including personnel, expanded space, computers, and vehicles. All facilities expanded case management staff (often quadrupling staff numbers over two or three years), with resultant stresses on the infrastructure. Many facilities made efforts to build multidisciplinary teams (including psychiatrists and psychologists, registered nurses and nurse practitioners, and substance use disorder and peer specialists). Some facility leaders further supported the multidisciplinary nature of HF by locating all homeless program staff in a single location. Many facility directors spoke proudly of new drop-in centers for which they had secured the resources and space. Indeed, facility leadership perceived resource provision as their primary contribution. As one observed, “There are some things I [as facility director] can make happen by virtue of my position: hiring, getting resources in the facility.”

Performance monitoring.

During the HUD-VASH expansion, two VA national performance metrics commanded the attention of VA facility leaders. Both metrics—time to placement of veterans in permanent housing and the proportion of housed veterans classified as chronically homeless—represent key aspects of HF. Emphasis on these metrics translated into frequent (sometimes daily) review by facility leaders, especially when performance lagged. Some staff reported that emphasis on rapid placement created the temptation to seek easy-to-house veterans (rather than more vulnerable veterans who might take longer to house), but despite this potentially misaligned incentive, performance monitoring left no doubt about program priorities among leadership and staff. As one facility director noted, “I didn’t bother the social workers every time we reported fewer than 65% (of vouchers) . . . to chronically homeless—maybe every other time [laughing]. But, we were very nervous.”

Centrality of middle management.

In contrast to senior facility leaders, who at most sites supported VA’s housing objectives without (by their own admission) fully comprehending the work involved, middle managers played a complex translational role that positioned them to influence perceptions of the possibility and practicality of the transition to HF among facility leadership, frontline staff, and the local community. Although structures differed, programs that were able to meet their goals and to maximize progress often had highly effective midlevel managers who worked with significant autonomy and authority (often informal) to champion the cause and get the work done. Typically, they enjoyed the trust of the local facility director and had either direct lines of communication with that director or strong representation through a deputy chief. There was evidence, however, that rapid growth and transition had strained some historic management structures. In the year preceding our interviews, two of the eight sites had reorganized their homeless programs or appointed new managers, and three more did so in subsequent months. Several sites were also considering new managerial roles in their homeless programs or the addition of new team leaders.

Discussion

Although HF has been studied as a housing intervention (

3,

11,

12), the complexity of its large-scale deployment has received less research attention. This study of eight VA facilities highlights organizational and logistic challenges that will influence the success or failure of such initiatives in the United States and elsewhere. Notable among them, the logistics of securing rental units (for example, cash availability, rental markets, and coordination with housing authorities) are substantial. The specific requirements of HF implementation have also led to tradeoffs between logistical and clinical recovery issues, requiring program managers to continually shape the task of case management.

We observed that crucial influence resides with midlevel managers, persons charged with organizing and translating the mission up and down a local chain of command. Both facility leadership and frontline staff were keenly aware of the pivotal role played by midlevel management. Facility leadership depended on midlevel staff to develop solutions to problems exposed in the expanded implementation of HF. Case managers reported relying on (and sometimes being frustrated with) midlevel managers’ efforts to facilitate frontline staff’s ability to meet veterans’ needs and goals. The numerous changes at the middle management level in our VA sample suggest a degree of strain resulting from program growth.

Our study illustrates the association between strong organizational management practices at the leadership level and success in meeting the challenges associated with moving HUD-VASH programs toward a HF approach, consistent with the organizational transformation model. Among facility leadership, enthusiasm and monitoring of goals appear to be common means of supporting implementation, although the willingness to align resources in support of the program is the strongest demonstration of true engagement in successful implementation. At the case management level, buy-in appears to be focused on successful manipulation of external conditions to achieve individual outcomes and a shared commitment to the mission of housing vulnerable veterans. For midlevel management, buy-in includes the ability to mediate between organizational goals and the specifics of implementing that vision.

The study had numerous strengths and limitations. Although the inclusion of multiple, carefully selected sites is a relative strength, the generalizability and inclusiveness of this sample is necessarily finite. Similarly, although the careful attention to recruiting individuals at all levels within facilities is a strength, insights could have been missed by not interviewing HUD-VASH program participants. The logistics and ethical requirements associated with including veterans in a multi-institutional VA study were prohibitive, but future research should include their perspectives. Finally it should be underscored that VA’s move toward HF remains an ongoing initiative and that important questions about how to sustain such transformations remain unanswered.

Analytically, the presence of multiple researchers, the production of copious notes, and the careful interpretive process represent significant strengths; however, transcriptions of recorded interviews would have captured more of the exact language used by individuals. Finally, these findings are cross-sectional, describing efforts at eight facilities in various stages of transition to HF at a specific point in time. Follow-up interviews are currently being conducted to assess programmatic changes after the reiteration of HF as VA policy in late 2012.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, there has been no prior scholarly examination of the practical considerations and organizational factors involved in ending homelessness through expansion of supportive housing. Although the VA is in some ways unique, the challenges profiled here are not. Both the logistic challenges described here and the challenges faced by managers at the interface of facility leadership and frontline staff are likely to have important analogs in other communities. In brief, Housing First cannot proceed unless there is organizational ability to secure housing in discrete geographies and markets. And securing housing while simultaneously advancing the recovery agenda for each client remains an ambitious undertaking.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grant SDR-11-233 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development branch. The authors thank N. Kay Johnson, B.S.N., M.P.H., and Carolyn Ray, J.D., for their assistance. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the positions of the VA or the U.S. government.

The authors report no competing interests.