Despite efforts to avert discrimination at the policy, structural, and interpersonal levels across the globe (

1,

2), discrimination against people with mental illness who are in recovery continues to persist in every aspect of life, including education, housing, employment, and everyday social interactions (

3–

5). A particularly significant finding is that people in recovery from or in mental illness often experience stigma when receiving health care and human services (

6–

8). Schulze and Angermeyer (

9) found that stigma in mental health care settings constitutes nearly one-fourth of the stigmatizing experiences of people in recovery. Similar to the findings on stigma in the general public, other studies have found repeatedly that health care service providers endorsed negative stereotypes toward and social distance from people with mental illnesses (

10,

11). Such experiences may exacerbate the internalization of stigma among people in recovery and compromise their full engagement in the recovery process (

12,

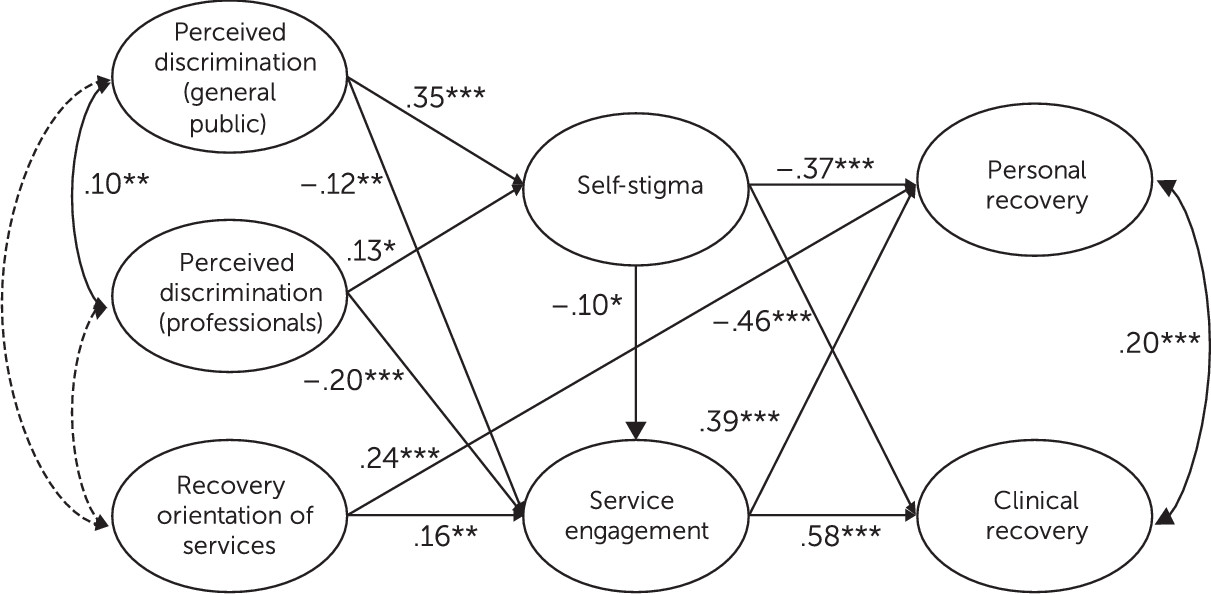

13). Building on the previous literature, this study developed a mediation model on how perceived discrimination affects self-stigma and service engagement, and, subsequently, clinical and personal recovery among people in recovery. The hypothesized mediation model is shown in

Figure 1.

Previous studies have shown that people in recovery who are exposed to discriminatory behaviors from the public and from service providers may endorse and concur with the negative stereotypes applied to them—a process known as “self-stigmatization” (

14). In addition to being an impetus to self-stigmatization, recurring experiences of discrimination can deter individuals from help seeking (

15), treatment participation (

16), and medication adherence (

17) and increase their risk of premature service termination (

18). Finally, apart from its direct impact on service engagement, discrimination may also reduce care-seeking behavior and adherence to psychiatric treatment through increased levels of self-stigma (

19).

Increased self-stigmatization can undermine the overall recovery of people with mental illness. Previous studies have consistently identified two dimensions of recovery, namely clinical recovery and personal recovery (

20,

21). Clinical recovery refers to the alleviation of psychiatric symptoms and the restoration of premorbid functioning (

22,

23). Previous studies have found that among people in recovery, those who reported more frequent stigmatizing experiences tended to have higher levels of depressive symptoms (

24) and emotional discomfort (

25), accounting for their baseline symptom severity. Drapalski and associates (

26) went a step farther by incorporating self-stigma into the relationship between discrimination and clinical recovery and demonstrated that people who internalized stigmatizing experiences tended to have more severe psychiatric symptoms. In addition to examining self-stigma, previous investigations have shown that treatment disengagement was also related to more frequent reporting of psychiatric symptoms and relapse of illness (

27). Killaspy and colleagues (

28) found that persons with inconsistent patterns of psychiatric appointment attendance were associated with greater severity of mental illness and higher risks of hospital readmission.

Apart from the clinical aspect of recovery, personal recovery is conceptualized as an individual’s potential for attaining a self-directing and fulfilling life despite the impairments imposed by mental illness (

12). The term “people in recovery” used throughout the article corresponds to the above understanding of recovery and positively conveys that individuals with mental illness can lead prosperous lives regardless of symptoms and dysfunctions associated with their mental health conditions. Studies have shown that people in recovery who had higher levels of perceived stigma and self-stigma were more likely to have diminished well-being and life satisfaction (

29) as well as less fulfillment of personal goals and personal life meaning (

30). Muñoz and colleagues (

31) also underscored the importance of stigma and discrimination experience in aggravating self-stigma and diminishing the expectations of personal recovery. Although stigma is widely conceived to have adverse influences on recovery, very few studies have attempted to simultaneously investigate the effect of perceived discrimination and self-stigma on both clinical and personal recovery (

20,

21). This study aimed to offer an integrated understanding of recovery from both clinical and personal perspectives.

The extent to which mental health services are recovery oriented is pivotal in influencing service users’ level of service utilization and personal recovery (

32,

33). Recovery-oriented practice represents a fundamental shift from a disorder-focused approach to a holistic approach to psychiatric care that emphasizes shared decision making, user involvement in service delivery, and provision of strength-based and individualized services (

34). Sells and colleagues (

35) showed that people who received peer-based care management perceived higher positive regard and acceptance from their service providers and demonstrated greater engagement in community services than those who received regular care management. Other studies also indicated that recovery-based treatment orientation was associated with greater consumer empowerment, better quality of life, improved functioning, and higher satisfaction with services (

36,

37). Given its impact, recovery orientation of mental health services was accounted for in the hypothesized model.

This study empirically tested the mediating roles of self-stigma and service engagement in the relationship between perceived discrimination and recovery. We hypothesized that perceived discrimination from the general public and from health care professionals would be positively associated with self-stigma. Self-stigma would be negatively associated with clinical recovery and personal recovery. We hypothesized that perceived discrimination from both the general public and health care professionals and self-stigma would be negatively associated with service engagement, which would be positively associated with both clinical and personal recovery. Recovery orientation of mental health services would be positively associated with service engagement and personal recovery. Given that previous studies have shown that individuals with different psychiatric disorders experience varying levels of stigma (with individuals with psychotic disorders being the most stigmatized, followed by individuals with substance use disorders or with mood disorders) (

38), this study investigated potential differences in the ways that perceived discrimination affects recovery among individuals with psychotic disorders, mood disorders, or substance use disorders.

Methods

The study was approved by the clinical research ethics committees of the authors’ institution and the hospitals involved in participant recruitment. A convenience sample of 374 people in recovery was recruited from seven public specialty outpatient clinics and substance abuse assessment clinics from various districts in Hong Kong. After giving informed consent, participants were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire. Upon completion, each participant received a HK$100 (US$13) coupon as compensation.

Measures

Perceived discrimination from the general public.

The ten-item discrimination subscale of the Stigma Scale is rated on a 5-point scale to assess the extent to which participants encountered discrimination in different spheres of their lives due to their mental illness (

39,

40). Higher scores indicate greater perceived discrimination from the general public (Cronbach’s α=.87).

Perceived discrimination from health care professionals.

Participants rated the four-item discrimination experience subscale of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale on a 5-point frequency scale (

41). Items were adapted to assess the extent to which participants encountered discriminatory behavior from their service providers. Higher scores indicate greater perceived discrimination from health care professionals (Cronbach’s α=.71).

Self-stigma.

The nine-item Self-Stigma Scale is rated on a 4-point scale to measure the extent to which participants internalize stigma toward people with mental illness (

42). Higher scores indicate greater endorsement of self-stigma (Cronbach’s α=.91).

Mental health service engagement.

Participants rated the adapted 14-item Service Engagement Scale on a 4-point scale to assess their own engagement with psychiatric treatment and community mental health services (

43). The phrase “the clients” in the original items was changed to “I” to make the items more relevant for self-report by people in recovery (

44). Higher scores indicate greater service engagement (Cronbach’s α=.79).

Recovery orientation of services.

Participants rated the 32-item Recovery Self-Assessment–Revised Person in Recovery version on a 5-point scale to indicate the extent to which the mental health services they had received were recovery oriented (

45,

46). Higher scores indicate a greater extent of recovery orientation (Cronbach’s α=.93).

Clinical recovery.

The 24-item Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale, which has been validated among individuals with a wide range of psychiatric disorders, including psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and substance use disorders, was used to evaluate level of clinical recovery on a 5-point scale over six dimensions (depression and functioning, interpersonal relationships, psychosis, substance abuse, emotional lability, and self-harm) during the past week (

47). The scores were reverse coded, with higher scores indicating better clinical recovery (Cronbach’s α=.92).

Personal recovery.

The 24-item Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (

48,

49), the 27-item Recovery Markers Questionnaire (RMQ) (

50,

51), and the 18-item Test Life Satisfaction Scale (TLSS) (

52,

53) were used to measure, respectively, the subjective perception of personal recovery, process and intermediate outcomes of personal recovery, and life satisfaction. The three scales are rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating more positive perception of personal recovery (RAS), better recovery process (RMQ), and higher level of life satisfaction (TLSS). Cronbach’s alphas of the RAS, RMQ, and TLSS were .94, .95, and .95, respectively.

[Sample items and response category of the measures are provided in the online supplement to this article.]

Data Analysis

A two-step approach to structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted with Mplus version 5.1 (

54). On confirmation of the latent factor structure with confirmatory factor analysis, we performed SEM to examine the hypothesized relationships in the proposed model (

55). The overall model fit was assessed by a combination of fit indices, including chi-square statistics, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (

56). In addition, a multisample SEM was conducted to examine whether the hypothesized relationships would hold across people with different mental illnesses. Invariance analysis suggested by Byrne (

56) was performed to examine the measurement and structural equivalence across the three groups of people with different psychiatric diagnoses. Mediation effects were tested with the bootstrapping procedures recommended by Shrout and Bolger (

57). Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals were estimated with 1,000 bootstrapped samples from the original data (

58). The details of data analysis are provided in the

online supplement.

Results

Among the 374 participants, half (50%, N=187) were male. The mean±SD age of the participants was 43.47±12.76 years. The most prevalent primary diagnosis that participants reported was mood disorders (43%, N=160), followed by substance use disorders (33%, N=124) and psychotic disorders (24%, N=90). Their mean duration of mental illness was 7.19±7.76 years. Close to two-thirds of the participants had attained secondary school education (63%, N=233). More than one-third of the participants were single (42%, N=157), and most were taking psychiatric medication (88%, N=326). Refer to

Table 1 for participants’ demographic details.

Table 2 shows the intercorrelations between the variables. Results of the correlation analysis were consistent with our predictions and provided preliminary evidence for further analysis of the proposed model.

Model on Recovery With the Entire Sample

Findings suggested a good fit of the measurement model (the relationship between observed indicators and latent constructs was explored in model 1). Model fit statistics are reported in

Table 3. SEM that examined the hypothesized relationships in the proposed model (model 2) also showed a good model fit.

Model on Recovery Across Diagnostic Groups

Multisample SEM was conducted to examine whether the hypothesized relationships would hold across the three subsamples. The configural invariant model (model 3) yielded an acceptable model fit, indicating that the same model configuration held across groups. Next, factor loadings of all variables were constrained to be equal across groups (model 4). Results showed an acceptable fit across groups. A chi-square goodness-of-fit test indicated that there was no significant difference in model fit between models 3 and 4, indicating that the invariance of factor loadings across groups was supported. Finally, structural parameters (including path coefficients and factor covariance) between all latent factors were constrained to be equal across the three subsamples (model 5). Results showed that the structural parameters–constrained model demonstrated a reasonable model fit, given its complexity (

59). The nonsignificant result of the chi-square goodness-of-fit test indicated that model 5, which imposed equality constraints on structural parameters, was preferred. These findings suggest that the structural paths were equivalent across the three diagnostic groups. [The

online appendix gives additional details about the results of the multisample SEM.]

Table 4 shows the standardized estimates of the path coefficients and the variance accounted for by the final model.

Results of bootstrapping analysis indicated significant indirect effects of perceived discrimination from the general public on clinical recovery (b=–.25, 95% confidence interval [CI]=−.37 to −.16) and personal recovery (b=–.19, CI=−.28 to −.12), respectively, via self-stigma and service engagement. Similarly, results showed significant indirect effects of perceived discrimination from health care professionals on clinical recovery (b=–.19, CI=−.33 to −.09) and personal recovery (b=–.13, CI=−.24 to −.06), respectively, via self-stigma and service engagement. Finally, recovery orientation of services was found to have significant indirect effects on clinical recovery (b=.09, CI=.03 to .17) and personal recovery (b=.06, CI=.02 to .12), respectively, via service engagement.

Discussion

Consistent with others’ findings (

16–

18,

31), this study showed that people in recovery who reported frequent instances of discrimination from the general public and from mental health professionals were more inclined than their peers to internalize the stigma associated with their mental illness and were less engaged in mental health services. In addition, people with higher self-stigma had lower levels of treatment engagement and illness self-management (

19).

This study was one of the first to attempt to simultaneously examine clinical recovery and personal recovery in the context of discrimination among people recovering in mental illness. Building on the literature on discrimination and recovery, in this investigation we extended the predominantly clinical conceptualization of recovery by including the development of a meaningful life as one of the dimensions of recovery. This two-pronged conceptualization of recovery corresponds to the understanding that mental health is a state of holistic well-being and not merely the absence of mental infirmity (

60). On the basis of our findings, perceived discrimination from both the general public and health care professionals was associated with increased internalization of stigma and reduced adherence of mental health services, thereby hindering clinical and personal recovery.

These findings highlight the importance of interventions that can effectively reduce stigma emanating from health care practitioners as well as from the general public. Antistigma training programs, which include personal stories from people with lived experience with mental illness and focus on building specific behavioral change skills, can be offered to service providers in social services and health care settings (

61). Contact-based education also should be integrated into the core curriculum for health professional trainees to diminish stigma in regard to mental health (

62). To empower people in recovery to reclaim an active role in managing their symptoms and leading a flourishing life, communitywide policies (including antidiscrimination laws and social inclusion initiatives) and intervention (such as advocacy and media campaigns) must be implemented to reduce discrimination and enhance the awareness of human rights in society (

63). In addition, cognitive restructuring strategies can be used to challenge the stigmatizing beliefs among people in recovery to reduce their stereotype endorsement and self-concurrence (

64,

65). Future intervention can also target building critical consciousness to enable individuals to recognize the illegitimacy of discrimination and reject stigma as unjust, which can buffer the harmful effect of discrimination and protect against stigma internalization (

66,

67).

In addition to demonstrating the detrimental effects of discrimination, this study also revealed the direct and indirect effects of recovery orientation of mental health care on recovery. Specifically, people who perceived their services as less person centered, as limiting service users’ involvement, and as not offering choice and diversity were more prone to poorer personal recovery. Moreover, negative perceptions of the recovery orientation of services were associated with lower service engagement, which was associated with an amplification of psychiatric symptoms and a diminution of personally valued life. Given the importance of recovery-oriented services, we recommend that health care and human service providers consider bringing about a recovery-oriented transformation in their service design and delivery. For example, strengths-based assessment, person-centered care planning, and Wellness Recovery Action Planning have been introduced as recovery-promoting practices, with accumulating evidence supporting their efficacy and effectiveness in clinical and personal recovery (

51,

68–

70). Organizations should also involve people with lived mental illness experience in service planning and provision, such as participation in advisory committees, staff development, and delivery of peer support services (

71). The adoption of a recovery orientation may encourage people in recovery to participate fully in mental health services, thereby improving clinical and personal recovery (

32).

With recognition of the complexity of discrimination and its effects on recovery, this study treated people with mental illness as a heterogeneous group and included people with different categories of psychiatric diagnoses. We asked whether the experience of discrimination would universally or differentially affect recovery among people with psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and substance use disorders. As shown in the multisample analysis, perceived discrimination from the general public and health care professionals intensified self-stigma among people with different types of mental illness and hampered their service adherence, resulting in poorer clinical and personal recovery. Our findings offer empirical evidence that the underlying mechanism of discrimination and recovery concerns people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders but also people with other disorders, unlike what has been reported in the extant literature (

12,

20,

21). Although people with psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and substance use disorders might experience varying levels of discrimination from the general public and health care professionals, the influence of discrimination on recovery was found to be universal and could be generalized across people with different psychiatric diagnoses.

Despite the contributions of this study, some methodological limitations should be noted. First, the hypothesized relationships among the variables were tested on the basis of cross-sectional data, which restricted our ability to draw causal inferences. Future studies should consider adopting a longitudinal research design in which serial assessments of the same participants are obtained over multiple time points. Second, given that this study relied solely on self-report instruments, validity of the findings may be limited. To reduce the potential bias of self-report data and enhance assessment validity, we recommend that future studies incorporate behavioral measures in assessing service engagement and symptom severity. Confirmation of the participants’ primary diagnosis should also be sought from their service providers in future studies.

Conclusions

This study constituted a cross-diagnostic investigation by examining the impact of discrimination on clinical and personal recovery among people with psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and substance use disorders. From the perspective of policy implication, our findings on the deleterious effects of discrimination strongly suggest the need for evidence-based antistigma initiatives that are designed to dispel misconceptions associated with mental illness and eradicate discriminatory behaviors against people with mental illness. Furthermore, findings regarding the positive impact of recovery-oriented services suggest that health care and human service institutions should consider adopting recovery-oriented practices and conduct systematic evaluation of their effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Grace Leung and the staff of outpatient psychiatric clinics or substance abuse assessment clinics at the following hospitals for their assistance in data collection (in alphabetical order): Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Castle Peak Hospital, East Kowloon Psychiatric Centre, Kwai Chung Hospital, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin Hospital, and Northern District Hospital.