Antipsychotic drugs are commonly used to treat psychosis, self-injurious behavior (SIB), and aggression in mentally retarded (MR) patients. Despite efforts to reduce use of these drugs in this population,

1 some MR patients require maintenance neuroleptics. Bipolar and psychotic patients who fail to tolerate or benefit from conventional neuroleptics often improve with clozapine, so this drug should be a logical consideration for MR patients with similar conditions. Prescription of psychotropics in this population, however, often requires that extensive informed-consent materials be provided to patients, legal guardians, and overseeing human rights committees. The paucity of published recent experience with this drug in MR patients may discourage some patients and clinicians from considering clozapine for this population. We review the literature on the use of clozapine in MR patients and describe our experience with this drug in 10 mentally retarded individuals.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

We performed

medline and PsycINFO searches, obtained additional references from the bibliographies of relevant articles, and located 13 reports on the open-label use of clozapine for trials lasting from 1 day to 18 months in 74 patients with borderline-profound MR.

2–14 Of this group, 59 had no other psychiatric diagnosis and clozapine was prescribed as a nonspecific treatment for aggression and SIB; diagnoses in the remainder included schizophrenia (

n=9), schizoaffective disorder (

n=3), bipolar disorder (

n=2), and schizophreniform disorder (

n=1). Case reports of 3 of the 74 patients described adverse effects, but not therapeutic response.

4–6Aggression, SIB, psychosis, and tardive dyskinesia (TD), the most commonly cited indications for treatment, improved in 86% of patients during treatment with clozapine in doses ranging from 25 to 600 mg/day. Most reports did not clarify which symptoms improved most in which patients. Aggression and self-abuse occasionally improved even without remission of psychotic symptoms.

8,10Epilepsy is common in MR patients, and seizures are associated with clozapine use. Of 9 MR epileptic patients treated with clozapine in the reports reviewed, 6 were treated concurrently with anticonvulsants.

3,11 Having been seizure-free without anticonvulsants for many years, 1 patient developed seizures 1 year after starting 225 mg/day of clozapine.

10 Valproic acid (VPA) was added, and this patient continued on clozapine for 6 months without further seizures.

Common side effects of clozapine reported in this population included sedation, hypersalivation, and orthostasis. More serious reported side effects included dose-related periodic cataplexy,

11 neuroleptic malignant syndrome

4 (although attribution to clozapine has been questioned

10), priapism

5 (although attribution to clozapine is unclear because of simultaneous treatment with haloperidol), pancreatitis,

6 and fecal impaction with supraventricular tachycardia in a patient concurrently treated with oxybutynin.

10These reports have several important limitations: 1) the trials were all open label; 2) some reports provided insufficient data on concurrent medications, clozapine dosage, and indications for treatment; 3) outcome measures were quite variable and often not standardized; 4) VPA was started concurrently with clozapine in two patients, making attribution of clinical benefits to clozapine suspect; 5) only 2 patients had profound MR; 6) duration of follow-up was either unstated or ill defined in 5 reports.

Particularly because 51 of the patients were described in fairly impressionistic reports from the mid-1970s,

2,3 questions remained. First, how safe and well tolerated is clozapine in MR patients? Second, how effective is clozapine in this population? Third, for how long is the drug effective? We therefore add our experience, which provides some of the longest follow-up described to date, to the sparse literature on this topic.

METHODS

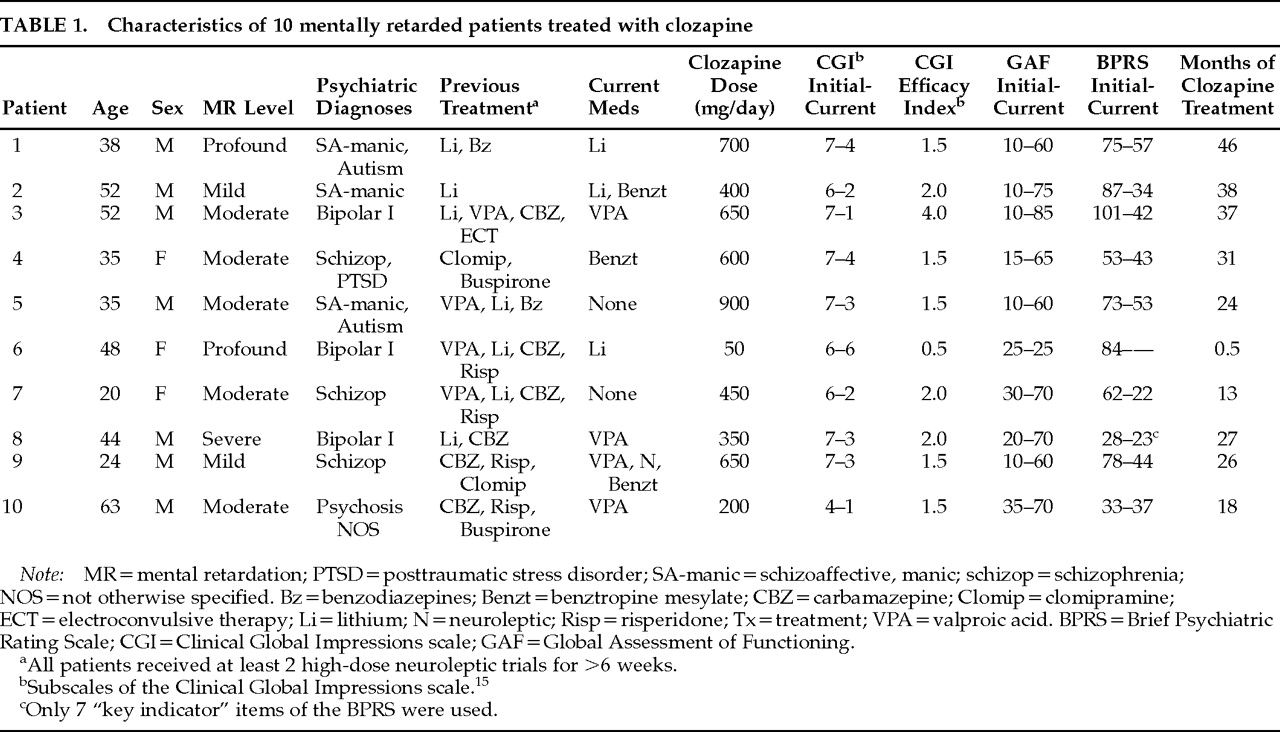

We reviewed the charts of all 10 MR patients we have treated with clozapine in institutional and community group homes. We made direct observations throughout the period of treatment (range 0.5–46 months;

Table 1). Outcome measures were the Clinical Global Impressions scale (CGI),

15 Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF), and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).

8Indications for treatment were psychosis or mania that had not responded to previous medications. Patient 10 was functioning well psychiatrically on fluphenazine, but he was started on clozapine because of severe TD that impaired his ability to ambulate.

CONCLUSION

Data from our patient series and from previously reported cases suggest that clozapine is well tolerated and efficacious for psychosis and mania in MR patients and that it may improve aggression and SIB independent of psychiatric diagnosis. Effectiveness does not appear to diminish over time. Although the duration of treatment described, 13–46 months, was probably sufficient to minimize the impact of placebo effects, our experience, like that of previous reports, is merely anecdotal. Controlled studies are needed to establish the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of this drug in this population. Clozapine is a unique drug, distinct from other neuroleptics, and MR patients with treatment-refractory aggression or SIB, especially if associated with bipolar illness, psychosis, or tardive dyskinesia, should be considered for treatment with this drug.