The diagnosis of depressive disorder in patients with somatic diseases, such as Parkinson's disease (PD), is often difficult because some of the physical symptoms of these diseases overlap with the somatic symptoms of depressive disorder. In patients with PD, the “masked facies,” psychomotor retardation, mental slowing, fatigue, and sleep disturbances may give the appearance of depression in euthymic patients. A lot of research has been directed to the

specificity of depressive symptoms in these patients, that is, to the question whether a certain symptom profile can be considered characteristic for depression in PD.

1–4 Although there is some evidence for a more prominent role of anxiety symptoms in depression in PD, the results of different studies are not consistent.

1–4 From a clinical point of view, however, the

sensitivity of depressive symptoms is more important. Clinicians are more interested in how to recognize depressive disorder in a patient with known Parkinson's disease than in the way depressive symptoms in PD patients differ from depressive symptoms in patients with other chronic diseases, or in otherwise healthy individuals. This study analyzes the contribution of individual depressive symptoms to the formal diagnosis of “depressive disorder” by using a discriminant analytic approach.

METHODS

As part of an ongoing research project on psychopathology in PD, 169 consecutive patients with primary PD, as defined by the clinical criteria of the United Kingdom Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank (UK-PDS-BB), were referred from the neurological outpatient department for a protocolized mental status examination.

5 This examination consisted of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV-Depression (SCID-D), to confirm or reject the diagnosis of depressive disorder as defined by DSM-IV criteria.

6,7 The DSM-IV diagnosis of depressive disorder was considered the gold standard in this study. Patients fulfilling the DSM-IV criteria for dementia were excluded in order to prevent unreliable answers due to recollection bias. All patients completed the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D),

8 irrespective of the presence or absence of depression. For 111 patients, the score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

9 was also available. Thus, in this study, the Ham-D and MADRS were used as symptom checklists and not as diagnostic scales. The physical disability of patients was rated according to the Hoehn and Yahr staging system,

10 which ranges from I (mild unilateral disease) to V (wheelchair-bound or bedridden unless aided). The cognitive status of the patients was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

11On the basis of the individual items of the Ham-D and MADRS, a discriminant model was calculated for both scales that would optimally predict whether patients would fall into the depressed or nondepressed group according to the gold standard (i.e., the DSM-IV criteria). Next, a correlation coefficient with this discriminant function was obtained for each of the individual items on these scales. These correlation coefficients reflect the relative strength of association of each symptom with the discriminant function, and can thus be considered an indirect measure for the contribution of these symptoms to the diagnosis of depressive disorder. Finally, the individual items were grouped in order of descending correlation coefficients, that is, in order of decreasing sensitivity. Wilks' lambda was calculated as a test of the discriminant function. As an indicator of the prevalence of individual depressive symptoms, the percentage of nonzero scores on each item of both scales is described. Means are accompanied by standard deviations. All analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 9.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

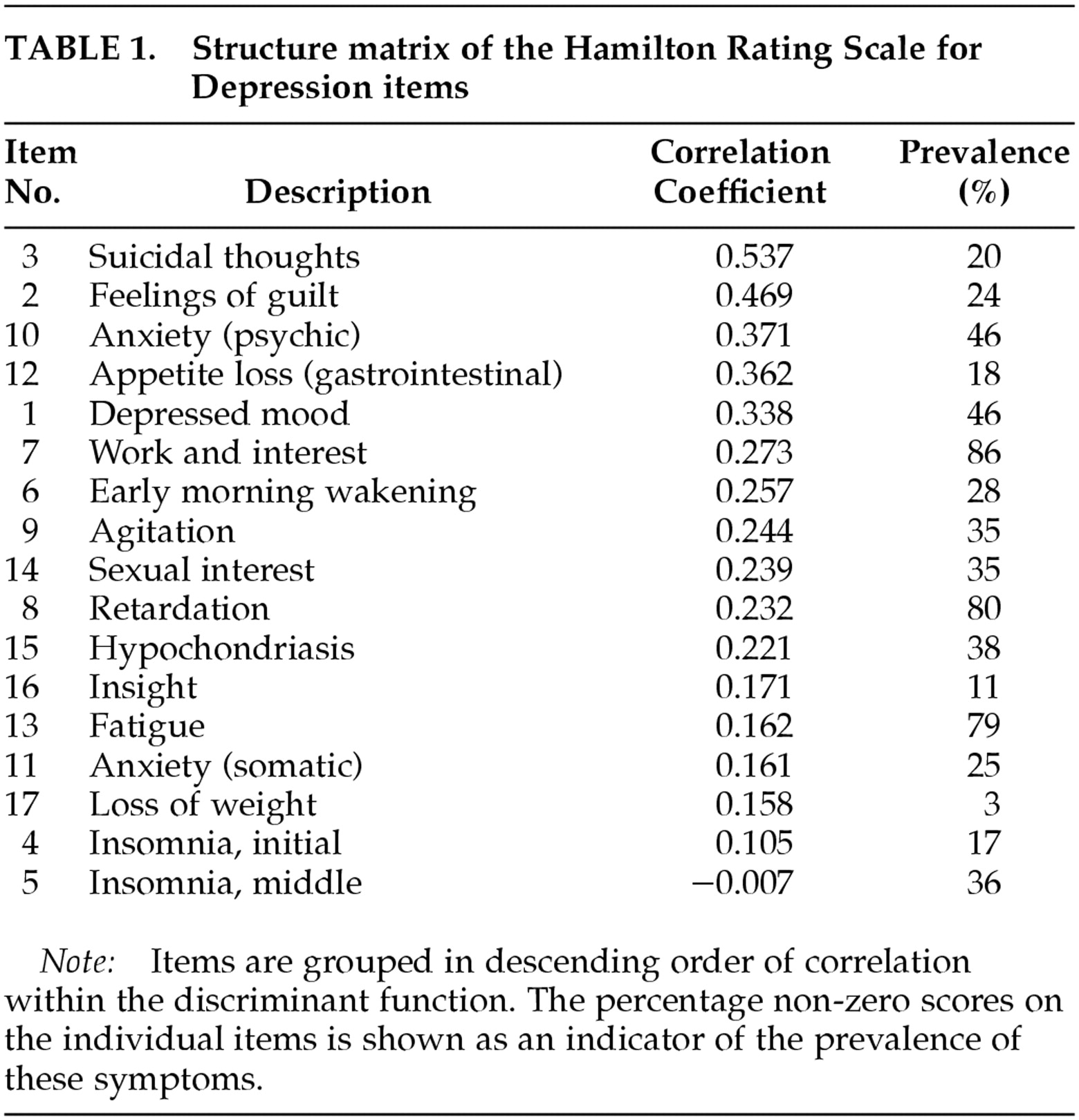

Of the 169 referred patients, 20 (11.8%) were excluded because of dementia. The other 149 patients participated in the analysis of the Ham-D items: 89 men and 60 women, with an average age of 66.8±0.2 years. Their average MMSE score was 27.4±2.3. According to the Hoehn and Yahr scale, 16 patients were classified as stage I, 81 as stage II, 24 as stage III, 9 as stage IV, and none as stage V (19 patients not staged). Thirty-three patients met the criteria for depressive disorder (22.1%). The average Ham-D score was 8.3±3.9 for nondepressed patients and 16.9±5.5 for depressed patients. The results of the discriminant analysis are shown in

Table 1. Wilks' lambda, as a test of the discriminant function in this model, was highly significant (λ=0.438, χ

2=108.502, df =17,

P<0.001). In this model, 93.0% of the patients were correctly classified as depressed or nondepressed.

In this discriminant model of the Ham-D, suicidality was the best discriminator between depressed and nondepressed patients. This item was followed, in descending order, by feelings of guilt, psychic anxiety, reduced appetite, depressed mood, and reduction of work and interest. Most somatic items, such as psychomotor slowing, tiredness, physical anxiety, and early and middle insomnia, had low discriminative properties. The exceptions were reduced appetite and early morning wakening (or late insomnia); these two somatic items had relatively high discriminative properties.

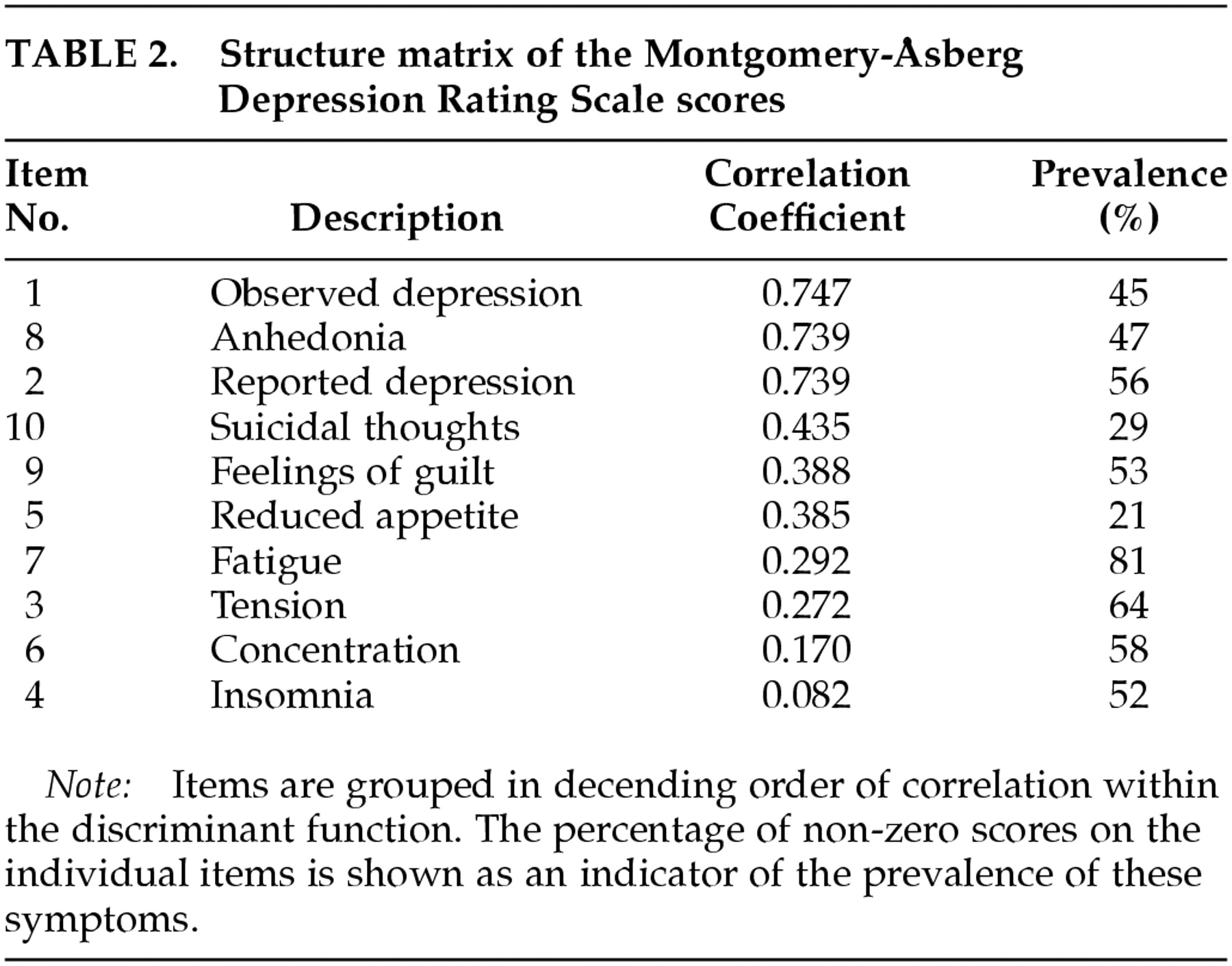

The MADRS was completed for 64 men and 47 women, with an average age of 68.1±10.1. The number of patients participating in this analysis was smaller than for the Ham-D because the MADRS was added to the protocol later. Their average MMSE was 27.2±2.4. Twelve were classified as Hoehn and Yahr stage I, 65 as stage II, 19 as stage III, 8 as stage IV, and none as stage V (7 patients not staged). Twenty-eight met the criteria for depressive disorder (25.2%). The average MADRS score was 8.4±5.1 for nondepressed and 20.5±8.4 for depressed patients. The results of the discriminant analysis are shown in

Table 2. In this model also, Wilks' lambda was highly significant (λ=0.419, χ

2=90.560, df=10,

P<0.001). This model classified 88.3% of all patients correctly.

In the discriminant model of the MADRS, the two “core” symptoms of depression, depressed mood and anhedonia, had the highest correlation coefficients. In the MADRS, the clinician's judgment of “apparent sadness” was the item that distinguished the best between depressed and nondepressed individuals. Somatic items of the MADRS, as well as the item “concentration difficulties,” had low correlation coefficients. However, as with the Ham-D, reduced appetite was a relatively important indicator of depression.

A post hoc analysis was performed for both the Ham-D and MADRS to discover in what way the percentage of correctly classified patients would be affected when only nonsomatic symptoms of depression were included in the analysis. After exclusion of the somatic items of the Ham-D (items 4, 5, 6, 8, 11–14, and 16), 86.6% of patients were correctly classified as depressed or nondepressed. After exclusion of the somatic items of the MADRS (items 4–7), 88.3% of the patients were classified correctly.

DISCUSSION

We studied the sensitivity and discriminative properties of somatic and nonsomatic symptoms of depression in a large sample of patients with PD. The prevalence of dementia and depressive disorder in this population, as well as the scores of both depressed and nondepressed patients on the Ham-D and MADRS, are comparable to findings in other studies.

12,13The discriminant analyses showed that core symptoms and other nonsomatic symptoms of depression were the most important symptoms for establishing the diagnosis of depressive disorder in patients with PD, as was expected. The results also showed that most somatic items in both depression rating scales do not contribute substantially to the discriminant model. This was also illustrated by the post hoc analyses: the percentage of patients who were correctly classified as depressed or nondepressed was hardly reduced by exclusion of the somatic items of the model. However, in the case of PD, not all somatic symptoms should be considered of little importance to the diagnosis of depression. Our analyses show that “reduced appetite” and “early morning wakening” meaningfully contribute to the discriminant model, and thus to the diagnosis of depressive disorder. In an attempt to prevent the inclusion of nonspecific symptoms in the diagnosis of depression, some authors argue that all somatic symptoms should be eliminated.

14–16 Our study does not support this often-advocated view. Instead, our study shows that somatic symptoms differ among themselves in terms of diagnostic sensitivity and that a more refined approach is warranted.

The discriminant analytic approach to the clinical problem of diagnosing depressive disorder in a patient with PD has both its advantages and its limitations. Less prevalent depressive symptoms may have a high discriminative power, whereas common symptoms may not have high discriminative properties. This may limit the clinical applicability of our findings in the individual patient. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients within the discriminant models do not reflect absolute values, but only the relative association of individual items with the discriminant model. Thus it is not possible to define cutoff values above which the contribution of a symptom should be considered relevant. For the same reason, correlation coefficients of the items of different discriminant models, such as those of the Ham-D and MADRS, cannot be compared. The major advantage of discriminant analysis is that it looks at the sensitivity, rather than the specificity, of individual symptoms for the diagnosis of depression. Therefore it may help the physician assign clinical importance to certain symptoms if they are present. In this way discriminant analysis facilitates a more refined approach to the diagnosis of depression in patients with physical disease, such as PD.

The recognition of depressive disorder in PD is often difficult because of the overlap of characteristic symptoms of this disease and the somatic symptoms of depression. The present discriminant analyses show that the core symptoms and other nonsomatic symptoms of depression are most important in distinguishing depressed and nondepressed PD patients. Most somatic items only have low discriminatory properties, with the notable exception of two symptoms that are relatively sensitive indicators of depression: reduced appetite and early morning wakening.