Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a clinical picture that can present when there is damage to the brain and nervous system as a complication of liver disorders. It is characterized by various neurologic symptoms, including changes in reflexes, consciousness, and behavior that can range from mild to severe.

1–3 HE has not been attributed to any one toxic substance or altered mechanism, but is considered to result from the combined effect of several factors.

1,3,4Hepatic encephalopathy can manifest in different stages or episodes (I, II, III, IV). However, before the first episode, or between episodes, cerebral function can be altered in a subclinical or latent manner.

5–7 Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy (SHE) is very frequent in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. In a sample of 165 cirrhotic patients, Das et al.

8 found that 62.4% had SHE. In SHE, patients appear to have a normal mental state, but they present subclinical cognitive alterations that can make it impossible for them to perform normal day-to-day tasks

9,10 that require correct cerebral function, such as driving, operating machinery, and other work-related activities.

5,6,11–14 Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy is therefore an important social problem. Moreover, in Western society hepatic cirrhosis is one of the 10 most common causes of death.

15 Between 51% and 70% of cirrhotic patients present cognitive alterations, although the social and health implications of this have so far been ignored.

16,17In the present study, cognitive deficits associated with hepatic cirrhosis were assessed by applying short tests that are easy to interpret. By this, we aimed to demonstrate that neuropsychological tests are a valid instrument to assess the mental capacities of patients with hepatic cirrhosis and liver transplant recipients.

RESULTS

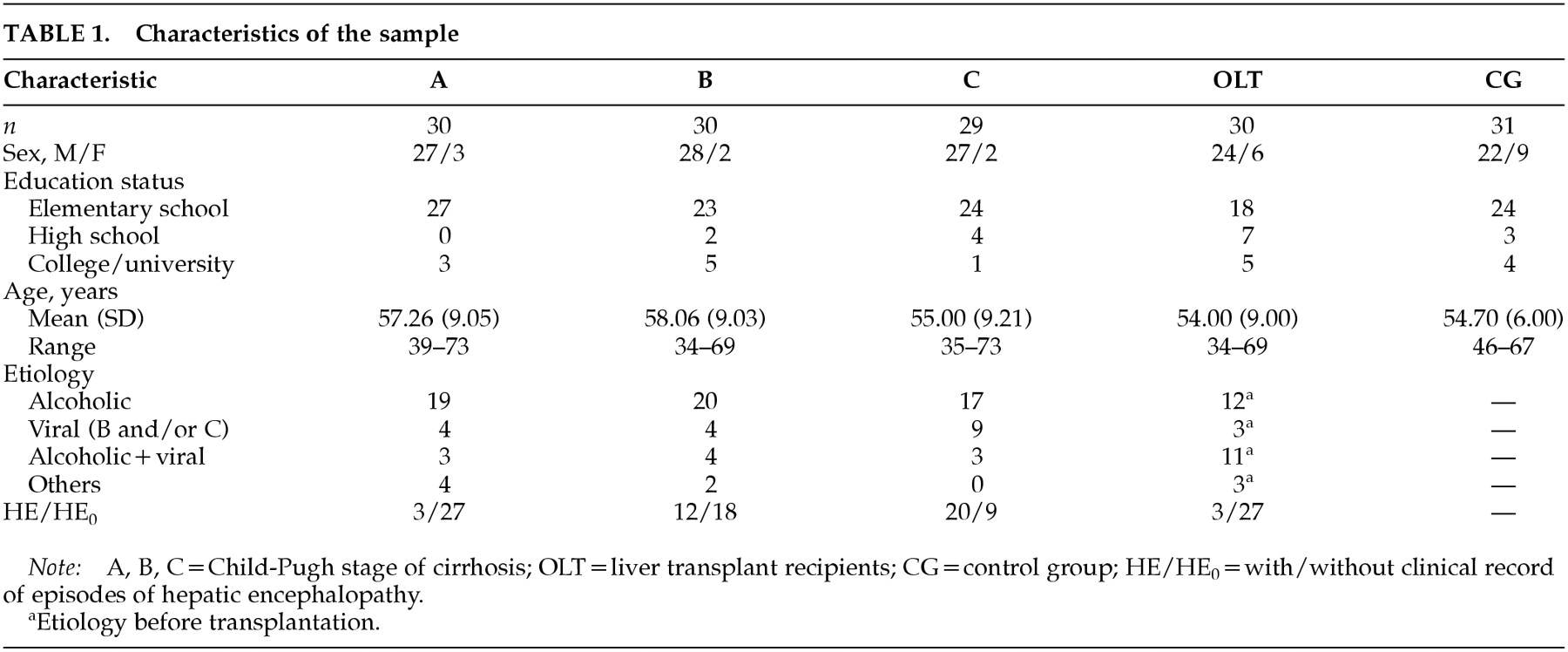

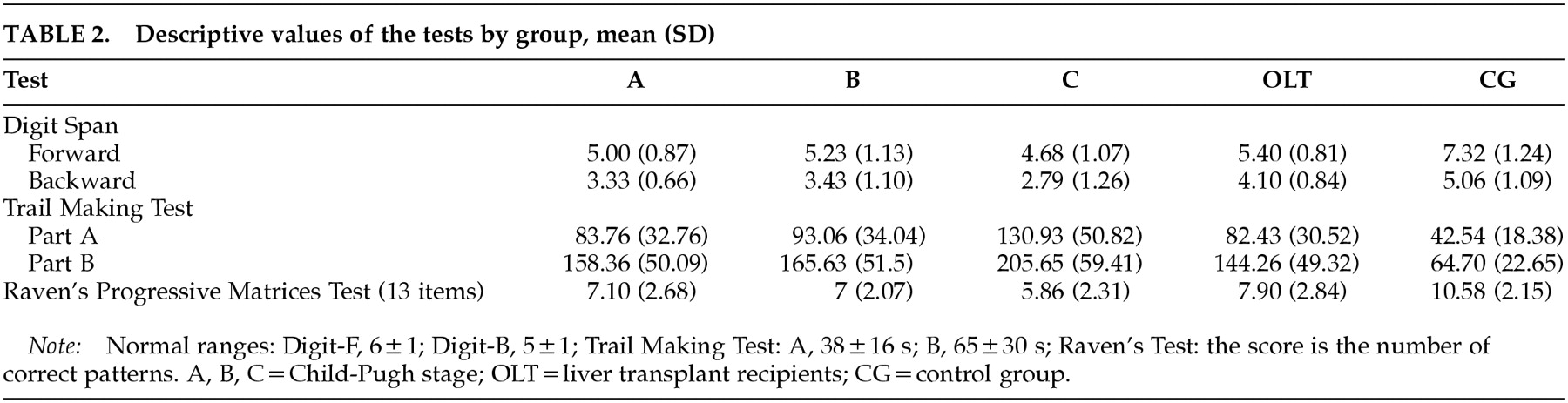

The results obtained from the scores of the five study groups on the five tests carried out are detailed in

Table 2. Because the Wilks' lambda value (converted to

F value) was

F=72.81 (df=72,87,

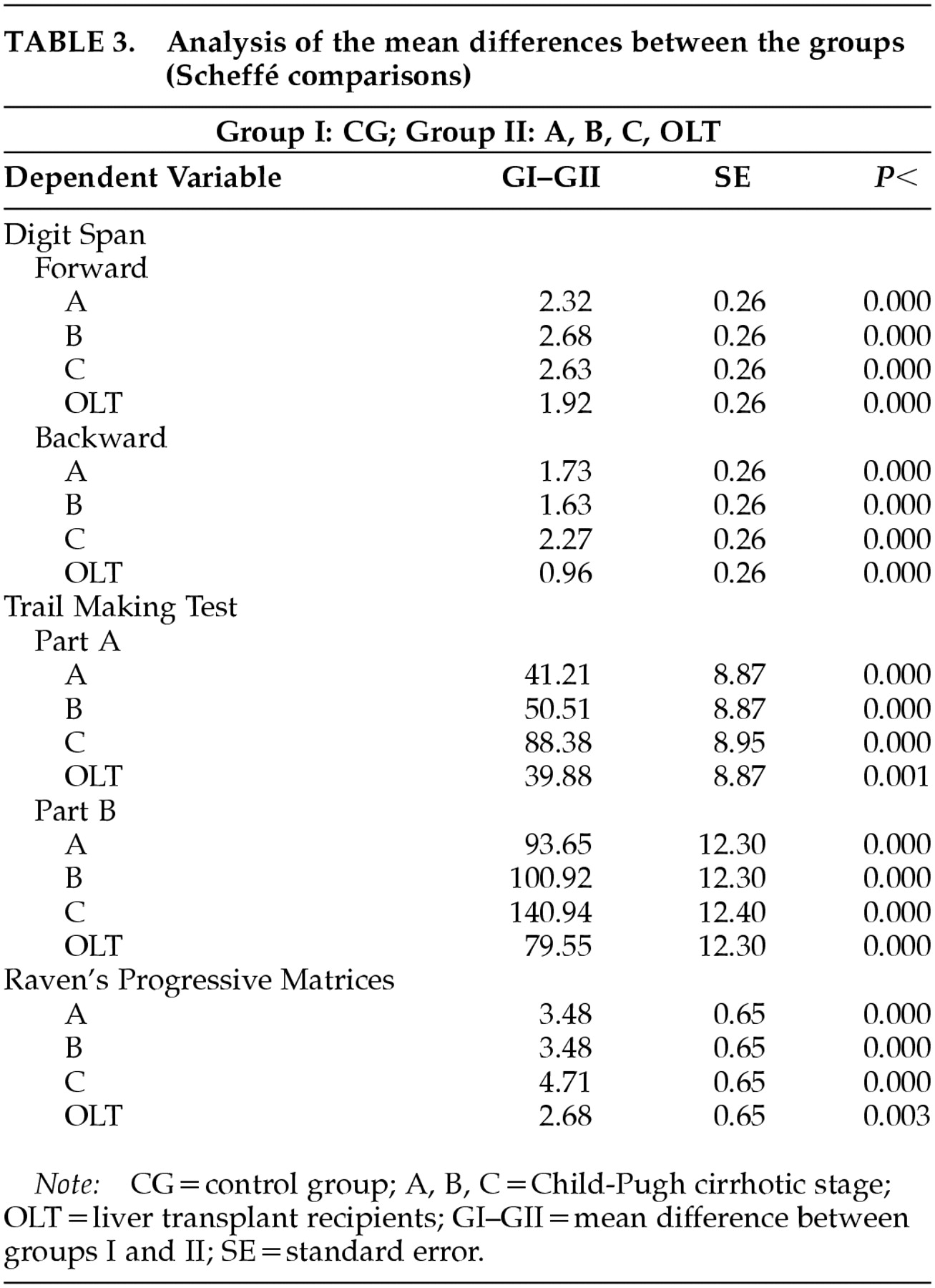

P=0.00), ANOVAs were carried out individually for each dependent variable. Differences in the performance of the patient groups on the tests in comparison to the control group are recorded in

Table 3. No statistically significant differences in test scores were found between etiologies or between genders.

On the Digit Span tests, significant differences were found between the four experimental groups and the control group (DF subtest: A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F= 873.68, df=5, 145, P=0.000; DB subtest: A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F=429.60, df=5, 145, P=0.000). Significant differences were also found between the transplant recipients and the cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh stage C on the DB test (C vs. OLT). On the TMT, there were significant differences between the four experimental groups and the control group (part A: F=204.32, df=5, 145, P=0.000; part B: A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F=308.28, df=5, 145, P=0.000). On parts A and B, the Child-C group had significantly worse results than the other patient groups (C vs. A, B, OLT). On the RT, there were also significant differences between the four patient groups and the control group (A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F=285.63, df=5, 145, P=0.000).

DISCUSSION

The neuropsychological tests that we administered confirmed the existence of cognitive impairment in patients with hepatic cirrhosis, and the deficit found was greater with increasing liver damage. Liver transplant recipients showed some degree of alteration in cerebral function in comparison to the control population, although they had better results than the group of cirrhotic patients.

On the Digits Forward and Digits Backward tests, subjects with OLT achieved higher direct scores than the groups with cirrhosis. On the DB test, the OLT group achieved scores within the normal range, reflecting a recovery of short-term memory. The DB test is clearly associated with functions of the temporal lobe and left frontal lobe,

27 and low scores on this test are characteristic of patients with dementia. On the DF test, the values obtained by subjects with OLT were within the normal range but toward the lower end, implying some improvement in attention capacity, which according to some authors is the main cognitive parameter impaired in cirrhotic subjects.

10 This improved performance in digit span tests had already been described by Oppong et al.

28 in patients assessed pre and post liver transplantation. In relation to the groups with hepatic cirrhosis, direct scores of Child-A and Child-B groups on DF were at the lower end of the normal range but were significantly different from the CG. However, the greatest deficit was reflected in the DB test results, suggesting alterations in short-term memory that could not be attributed to differences in age or educational level with the control group.

27 Results of the Child-C group showed that these subjects presented moderate dementia with auditory attention deficit and reduced short-term retention capacity.

On the other hand, the results of the TMT-A and B once again confirm that this is the most sensitive test to assess HE.

16,24 Its visual and motor components have been shown to be correlated with alterations in psychomotor and visuopractic processes found in cirrhotic subjects that can be inferred from changes occurring in the basal ganglia.

29 All experimental groups, cirrhotic patients and transplant recipients, presented some degree of mental deficit on TMT when compared with the healthy population. Here it should be borne in mind that only 30% of patients had previously suffered one or more episodes of HE, whereas 70% had never had any clinical manifestations of HE. Since the TMT correlates well with other tests of mental capacity and is very sensitive to brain damage,

30 the scores obtained by the different groups confirmed the existence of cognitive deficits. As with the Digit Span tests, there was also a clear correlation between Child-Pugh stage of cirrhosis and the scores obtained on the TMT. Thus, patients with Child-C had the worst cognitive deficit compared with the other groups. In this test, the OLT patient group showed significant differences compared with the control group on both part A and part B. Other authors have observed differences between OLT patients and control subjects on part A, but not on part B. This could be due to the lower age of their OLT patients compared with those used in our study

21,31 or to the range of time post transplant. This lack of recovery in OLT subjects could confirm the viewpoint of Tarter et al.

32 They maintain that HE is a neuropsychiatric illness which, in addition to metabolic dysfunctions, is also characterized by changes in cerebral morphology that would explain why OLT patients do not make a full recovery. On the other hand, both parts of the TMT are highly correlated with lesions of the caudate nucleus, again confirming the existence of alterations in the basal ganglia in HE subjects. The TMT is also highly sensitive to educational level and age, but no differences in test performance could be attributed to these variables because they were similar in all our groups. It is also worth noting the large differences between the times taken to carry out parts A and B in the patient groups, reflecting the difficulty that all patient groups had in interpreting complex conceptual clues.

27The results obtained by the different Child groups using the 13 illustrations of the RT showed an impairment in concrete thinking, which is a good reflection of conceptual functions. Low results on this test would reflect the inability to form concepts using categories, generalizations, or general rules. The selection of illustrations from different scales enables assessment of both visuoperceptive skills, which are clearly associated with the right hemisphere (scale A), and analogical reasoning capacity with a verbal component, which is associated with the left hemisphere (scales B and above). The Child-C group showed severely impaired conceptual capacity by making mistakes on more than 50% of the illustrations, permitting a clear association to be established between the severity of hepatic disease and the RT results. It was interesting that patients with OLT had better results on this test than patients with liver cirrhosis. However, as has already been reported by other authors, the results reflected some degree of impairment in the OLT group compared with the control group.

31,33On the other hand, because chronic alcohol consumption was the etiology of cirrhosis in 63% of the patients in our series, some of the mental alterations observed in our tests could have been due to this habit. Miller and Saucedo

34 have shown that alcoholics had lower scores on the RT, and Walton and Bowden

35 have established a correlation between the number of years of alcohol consumption and digit test results. However, our analysis of the etiology of the cirrhosis did not reveal significant differences between cirrhosis of alcoholic origin and the other etiologies, suggesting that hepatic dysfunction constitutes the main origin of the observed mental alterations. In relation to this, Gilberstadt et al.

36 found that alcoholics with cirrhosis obtained worse results in some tests than alcoholics without hepatic damage. Geissler et al.

37 also concluded that the morphological changes of cirrhotic patients are related to the degree of hepatic dysfunction and not to long-term alcohol consumption.

Our work shows that neuropsychological tests are valid for assessing HE. However, they are not unanimously accepted for reaching a cognitive diagnosis. For this purpose, some authors consider neurological imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance, which can detect a larger proportion of patients with subclinical hepatic encephalopathy than neuropsychological tests, to be more reliable.

38,39 Detecting these alterations is of considerable interest and importance because of the impact they have on the daily lives of these subjects

5 and because of the need to find therapeutic solutions to minimize these deficits.

6 In the future, it will probably be necessary to standardize the scores obtained by cirrhotic patients with different degrees of HE. When this is accomplished, by carrying out a series of short tests (less than 1 hour in total duration), the clinician will then be able to identify the degree of cognitive dysfunction of the patient and take the necessary prophylactic or therapeutic measures.