A growing literature suggests that obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) occur in a higher proportion of patients with schizophrenia than was originally suspected. Clinical and epidemiological studies suggest that more than one-third of individuals with schizophrenia display OCS, and prevalence rates for OCD have ranged between 7.8% and 40.5%.

1 –

3 Additionally, an elevated rate of OCD has been found in first episode and drug naive patients with schizophrenia,

1 indicating that it is not accounted for by the course of the primary illness or antipsychotic medication alone. The presence of OCD or significant OCS in patients with schizophrenia has been associated with more severe psychosis

4 and depression,

4 poorer social functioning,

2 lesser likelihood of being employed,

5 and poorer prognosis.

5 It has been suggested that comorbid OCS or OCD in schizophrenia may represent a specific pattern of neurobiological dysfunction.

6,

7 A number of studies have evaluated the relationship between neuropsychological functioning and OCS in schizophrenia, but the findings have been inconsistent. One study found a correlation between higher levels of OCS and poorer delayed visual memory, as well as decreased cognitive flexibility as measured by the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) and the Trail Making test.

8 Others have also observed an association between OCS and poorer executive functioning as measured by the WCST,

9,

10 though failures to find a relationship with either the WCST or other tests of executive function have also been reported.

11 –

13In patients with OCD who do not have schizophrenia, symptom subtypes such as hoarding, checking and washing have been found to be differentially associated with functional neuroimaging measures.

14,

15 In one factor analytic study of neuropsychological functioning, three major subsets of patients were observed with differential patterns of association between OCS subtypes and performance on the WCST and part B of the Trail Making test.

16 One subset of patients was impaired on both tests and had prominent contamination obsessions and compulsive washing. A second subset was intact on both tests and was characterized by aggressive obsessions. A third subset, consisting of a mixed group of patients with either prominent obsessions and aggression or prominent washing compulsions, was slow to complete the Trail Making test, with intact WCST performance. Another study found that patients with schizophrenia and comorbid OCD characterized by prominent checking symptoms showed poorer performance on tests of response inhibition and cognitive flexibility when compared with patients with primarily washing symptoms.

17 A relationship between more impaired executive function and checking has also been noted in studies of nonclinical samples.

18,

19 These findings suggest that the presence of different OCS subtypes may be contributing to the heterogeneity of relationships observed between OCS and neuropsychological functioning in patients with schizophrenia.

The current study evaluated the hypothesis that greater overall severity of OCS in patients with schizophrenia, who do not meet clinical criteria for OCD, would be associated with more impaired executive functioning as evaluated using questionnaire and performance-based measures. Based on the work in OCD, we also hypothesized that among the OCS subtypes, more severe obsessing, washing, and checking will be associated with poorer executive functioning.

RESULTS

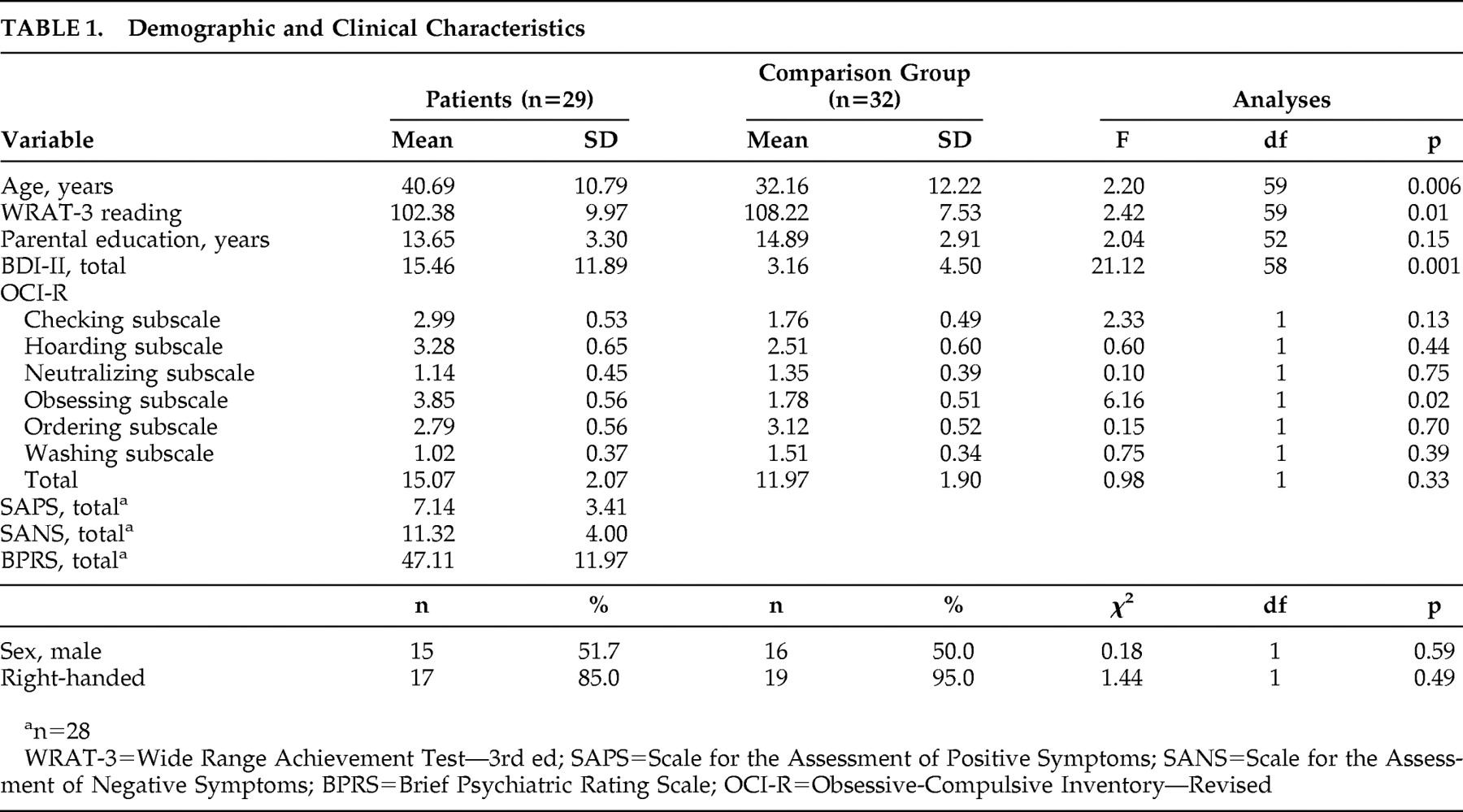

Table 1 presents the participant characteristic and clinical data. The groups were well matched for sex composition, handedness, and parental education. The patient group was significantly older (p=0.006), was more depressed (p=0.001), and had a lower reading standard score (p=0.01) than the healthy comparison group. These latter variables were therefore statistically controlled for in subsequent analyses. The schizophrenia group obtained a significantly higher score than the comparison group on the obsessing subscale of the OCI-R (p=0.02), despite controlling for age, reading and depression. Groups were equivalent on the other subscales and total OCI-R score. No significant correlations were observed between any of the OCI-R scores and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms, or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

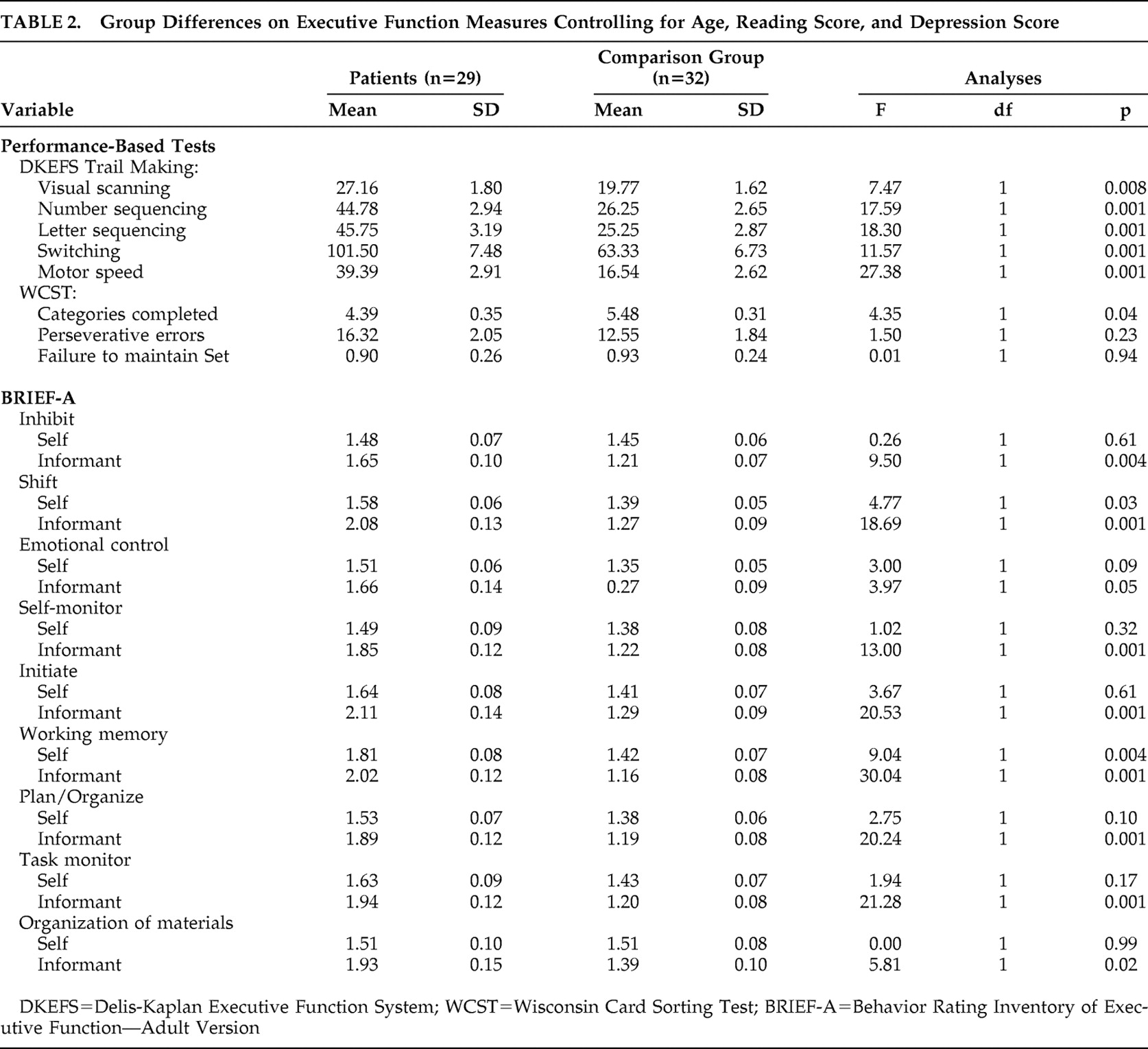

Table 2 presents the performance-based and the self- and informant-report executive function scores. Patients with schizophrenia performed significantly slower than the comparison group on all conditions of the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Trail Making subtest and completed fewer categories on the WCST. The patients reported having significantly greater problems with their daily executive functioning abilities on the BRIEF-A, including higher mean scores on the shift (p=0.03) and working memory (p=0.004) scales, with a trend noted for emotional control (p=0.09). Informant data showed significantly greater problems with the patients’ daily executive abilities for all BRIEF-A scales with the exception of emotional control, which was at the level of a trend (p=0.05).

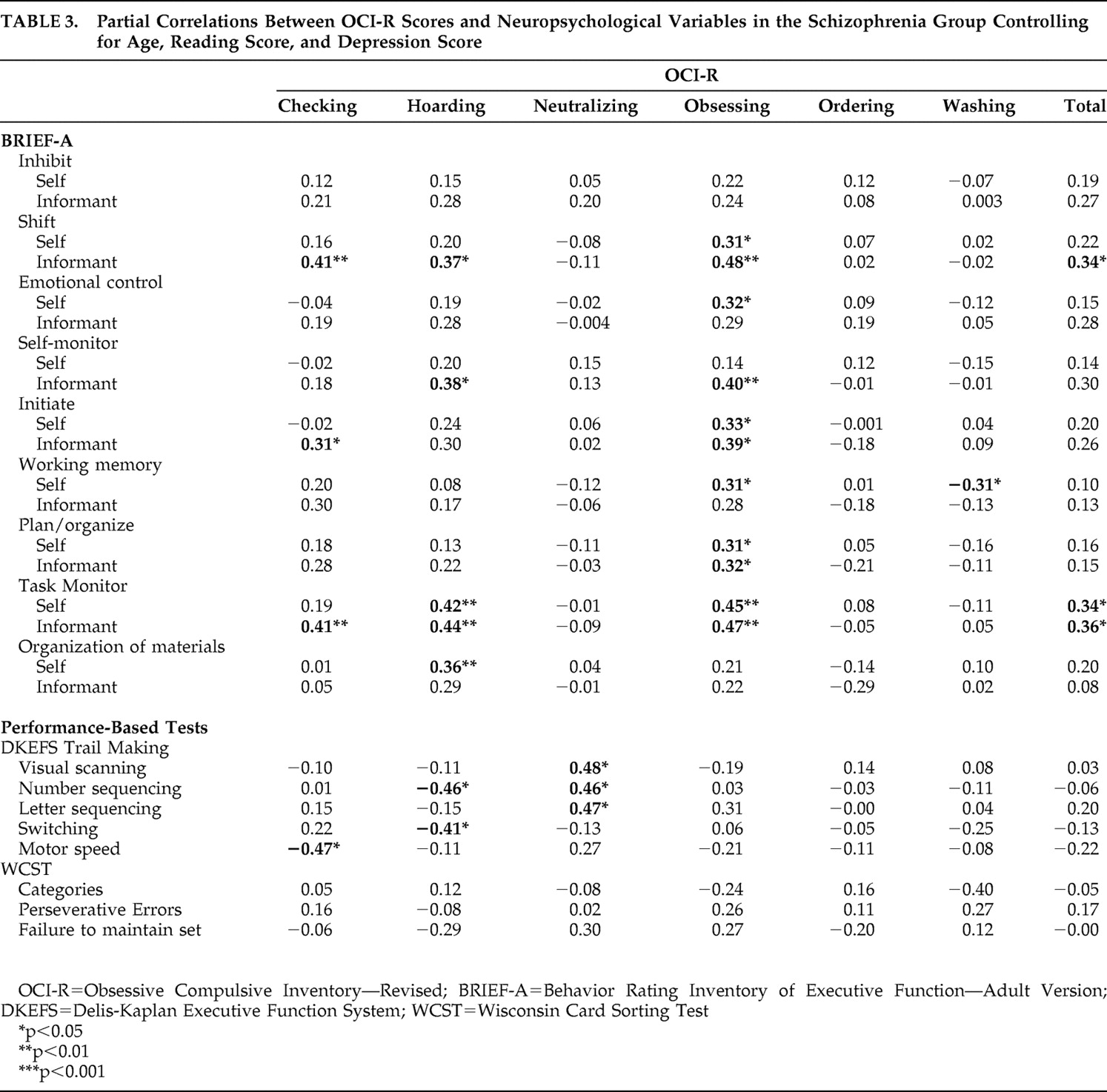

Table 3 presents the correlations between OCS severity and executive functioning measures for the schizophrenia group. With respect to self-reported executive functions, greater overall OCS severity was only significantly correlated with poorer scores on the task monitor scale. Among the OCS subtypes, only obsessing, hoarding, and washing severity were associated with self-reported problems in aspects of executive functions. Obsessing was associated with worse scores on the shift, emotional control, initiate, plan/organize, working memory, and task monitoring scales. More severe hoarding was related to poorer task monitoring and organization of materials. Washing was correlated with a better (i.e., less impaired) working memory score. As with the self-report, more severe obsessing was related to worse BRIEF-A informant-report shift, self-monitor, initiate, plan/organize, and task monitor scores. More severe hoarding was associated with poorer shift, self-monitor, and task monitor scores. Checking was correlated with worse shift, initiate, and task monitor scores.

The correlations between OCI-R responses and performance on executive functioning measures also differed depending on the OCS subtype. Greater overall OCS severity was not associated with neuropsychological performance on any of the administered tasks. Checking, hoarding and neutralizing symptoms were associated with aspects of Trail Making test performance, though only hoarding was associated with poorer switching ability. Performance on the WCST was not significantly correlated with any of the OCI-R scores.

DISCUSSION

Our group of patients with schizophrenia reported greater difficulty, relative to the healthy comparison group, with certain aspects of their executive functions in daily life including their ability to adjust to changes in routine and use their working memory. Additionally, the patients’ informants observed more difficulty with nearly all aspects of executive functions in daily life. The patient group also obtained lower scores than the comparison group on two performance-based measures of executive function, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Trail Making subtest and the WCST. These findings are consistent with the extant literature indicating the presence of executive dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia.

32With respect to OCS, the schizophrenia group was found to have higher scores than the comparison group only on the obsessing subscale of the OCI-R. This is inconsistent with previous literature suggesting that patients with schizophrenia experience multiple types of OCS.

33 In looking at the items that assess obsessive symptomatology on the OCI-R, it is worth noting that there is no overlap with symptoms that are specifically related to psychosis. Furthermore, we did not find a correlation between obsessing or any other OCS and the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. The presence of greater obsessing in the schizophrenia group thus cannot be accounted for by severity of the primary illness. Another possibility is that our comparison group’s OCS scores are higher than may be expected for a healthy adult sample, thereby reducing the likelihood of finding a significant difference between this group and the patient sample. The mean OCI-R score in our healthy group, however, is within a standard deviation of scores obtained in several other studies of the instrument in healthy adult samples,

21,

34,

35 arguing against this possibility. Further research is required to determine whether our finding is specific to the patient sample in the present investigation and, if so, what factors may be contributing to the heterogeneity of obsessive-compulsive symptom subtype presentation in different samples of patients with schizophrenia.

Overall OCS severity in the patients with schizophrenia was associated with poorer self- and informant-reported ability to monitor task performance for accuracy, as well as poorer cognitive flexibility per informant report. The former finding may be related to evidence from electrophysiological studies showing exaggerated performance monitoring in adults with primary OCD.

36 This may reflect the doubt that many of these patients have with respect to their compulsive behaviors, and/or reduced confidence in their cognitive abilities, particularly with respect to attention.

37 That overall OCS severity was correlated with cognitive flexibility is consistent with studies implicating this executive function in patients with primary OCD.

38Various subtypes of OCS have been reported to be differentially related to the integrity of neural circuitry and cognitive functioning in patients with primary OCD. In the present investigation, we observed that the severity of nonclinical OCS subtypes was also differentially related to executive functions in patients with schizophrenia who have never met DSM-IV criteria for OCD. Obsessing symptoms were associated with decreased ability to monitor task performance for accuracy, to initiate activities, to plan/organize tasks, and to think flexibly, as reported by both the patients and their informants. In addition, more severe obsessing was related to greater difficulty with emotional control and working memory per self-report and worse ability to monitor the effects of one’s behavior on others per informant report. That obsessing was associated with several executive functions may be especially noteworthy given that only this symptom subtype was reported as being more severe by the patient relative to the comparison group. Patients with primary OCD have also been reported to exhibit problems in cognitive flexibility and several other aspects of executive functions.

39,

40 We speculate that the nature of obsessing symptoms, being recurrent and requiring significant mental energy, might render it more difficult for an individual to allocate attentional resources to task-relevant cognitive processes such as monitoring, planning, working memory, and cognitive flexibility.

More severe hoarding behavior was related to poorer organization of materials needed for tasks per self-report. This appears consistent with the nature of hoarding, which involves the acquisition of, and failure to discard, a large number of generally useless possessions, causing significant clutter and interference with daily functioning. Hoarding was also found to be associated with more difficulty with task monitoring per self and informant report. This finding may be related to evidence that patients with compulsive hoarding have slower reaction times and difficulty distinguishing target and nontarget stimuli on performance-based neuropsychological measures.

41 Finally, hoarding was related to worse informant report cognitive flexibility and monitoring of the effects of one’s behavior on others.

Prior investigations have reported an association between compulsive checking and poorer scores on performance-based tests of executive function in nonclinical samples

18,

19 and in patients with schizophrenia and comorbid OCD.

17 In our schizophrenia group we observed a relationship between more severe nonclinical compulsive checking and worse executive functions in daily life per informant report, specifically for cognitive flexibility, initiation, and task monitoring. Checking was unrelated, however, to performance-based measures of executive functions. Indeed, in contrast to the self and informant report measures, few correlations were found between OCS subtypes and executive function as assessed via performance-based tests. Hoarding was associated with decreased cognitive flexibility on Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Trail Making subtest but not on the WCST. This is consistent with a study of patients with primary OCD which found that hoarding was unrelated to WCST performance.

38 The lack of relationship between WCST performance and severity of nonclinical OCS is consistent with several studies that have failed to observe a relationship between the WCST and OCS in schizophrenia.

11 –

13Overall, our findings are generally consistent with previous work indicating that OCS in patients with schizophrenia may represent a specific pattern of neurobiological dysfunction.

6,

7 Furthermore, the results indicate that nonclinical OCS can contribute to the heterogeneity of cognitive functioning commonly seen in studies of schizophrenia. It is important, however, to note limitations of this study. The possibility of a type I error is increased given the multiple statistical comparisons conducted. In addition, the correlational nature of the study precludes determination of a direction of causality, that is, whether more severe nonclinical OCS contributes to greater executive dysfunction or vice versa. We hypothesize that the considerable evidence indicating the presence of executive dysfunction in primary OCD suggests that the latter relationship is more likely. An additional limitation is that the modest sample size may limit generalization of the results. Replication in a larger sample of patients with schizophrenia and nonclinical OCS will be important. Finally, determination of the specificity and generalizability of the pattern of nonclinical OCS and their association with executive functions in schizophrenia would benefit from direct comparison to patients with primary OCD and to healthy adults with high levels of nonclinical obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

In summary, the present findings indicate that the integrity of executive functions in schizophrenia may depend in part on the subtype of OCS exhibited, even when these symptoms are at a nonclinical level. Furthermore, the presence of specific OCS subtypes may have implications for treatment planning. Certain OCS subtypes, such as hoarding, have been associated with poorer responsiveness to standard pharmacological and behavioral treatments in patients with primary OCD.

42 It is possible that OCS subtype also contributes to the responsiveness of OCS to treatment in schizophrenia, raising the need to consider alternative treatment strategies. Additionally, evidence of a contribution of executive functions to OCS in schizophrenia suggests that the application of cognitive remediation strategies may not only help such patients with executive dysfunction

43 but perhaps also ameliorate their obsessive-compulsive symptoms.