At Index

Findings vary slightly from the original report, mostly because the authors of the DIS have announced a recommendation for changes in the scoring algorithm for alcohol and drug use disorders (

13) but also because it was discovered that in the original data set, one male subject had been miscoded as female. These adjustments were made in the data set. The main difference in findings with these adjustments was that the rates of alcohol and drug use disorders increased. All main analyses from the original report were reperformed with these changes, and there were no changes in significant differences in the overall findings.

Fifty-three percent of the subjects were women. Mean age was 38.7 years (SD=14.2). Eighty percent were Caucasian, 10% African American, 8% Hispanic, and 2% other races. Subjects had completed a mean of 13.2 years (SD=2.4) of education. Two-thirds (67%) were currently married. Age, marital status, ethnicity, and predisaster history of psychiatric diagnosis did not differ between men and women, although men were slightly better educated (mean=13.9 years, SD=2.1, versus mean=12.7 years, SD=2.5) (Student's t=2.94, df=129, p=0.004).

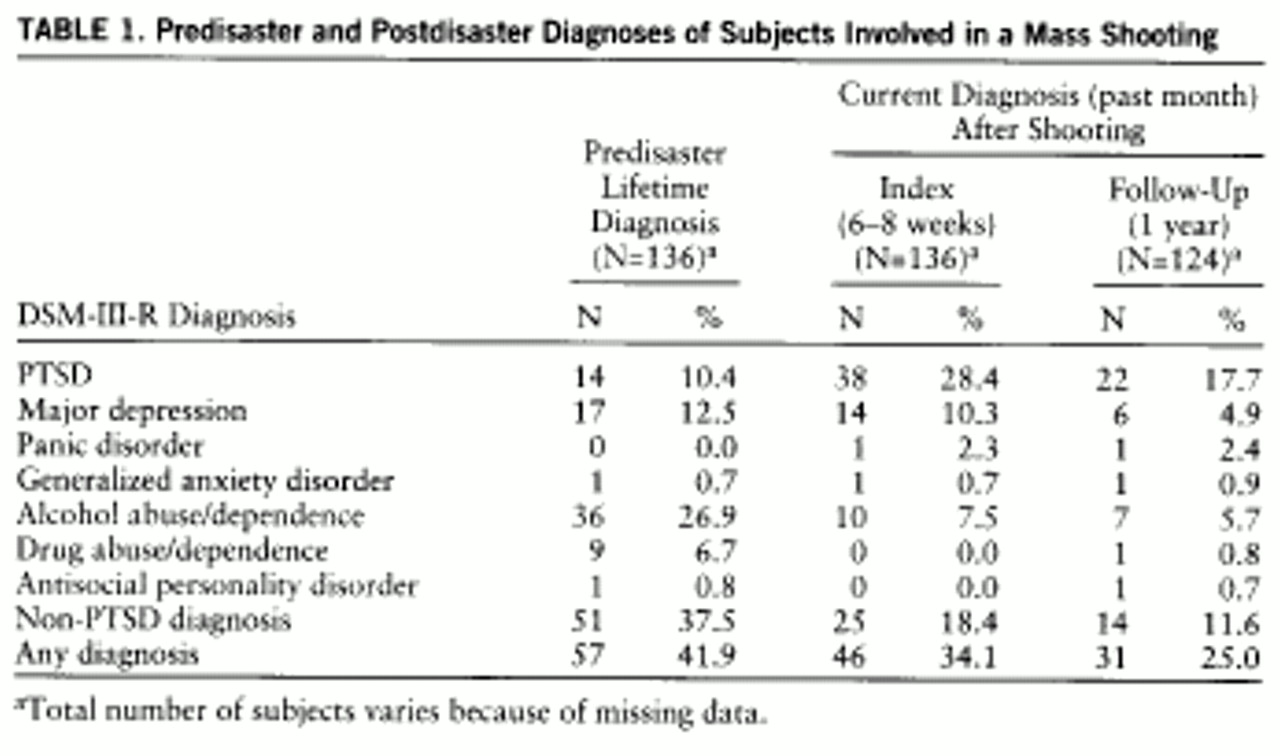

Table 1 shows rates of predisaster and index psychiatric disorders at index and current (1-month) disorders a year later. More than one-third of subjects reported a predisaster psychiatric disorder. One subject had PTSD related not to the disaster but to another event. At index 27.2% (N=37) met criteria for PTSD related to the shooting. PTSD at index was not predicted by category of exposure to the disaster or by any demographic variable. Nearly one-fifth (18%) of the group met criteria for a postdisaster non-PTSD diagnosis.

Of subjects reporting PTSD at index, the majority (68%) described onset of symptoms the day of the incident. Some (22%) reported onset during the week after the incident, and a few (11%) later in the month.

Follow-Up Data

As seen in

table 1, the most prevalent current disorder at follow-up was PTSD, which was present in 18% of the subjects (including one subject with PTSD unrelated to the disaster), a significant difference from the rate of 28% at index (McNemar's χ

2=9.00, df=1, p=0.003). Rates of current disaster-related PTSD at index and follow-up were 27% and 17%, respectively (McNemar's χ

2=6.76, df=1, p=0.009). Only 12% of all subjects reported another active psychiatric disorder, a nonsignificant decrease from the 18% reported at index (McNemar's χ

2=3.20, df=1, p=0.07).

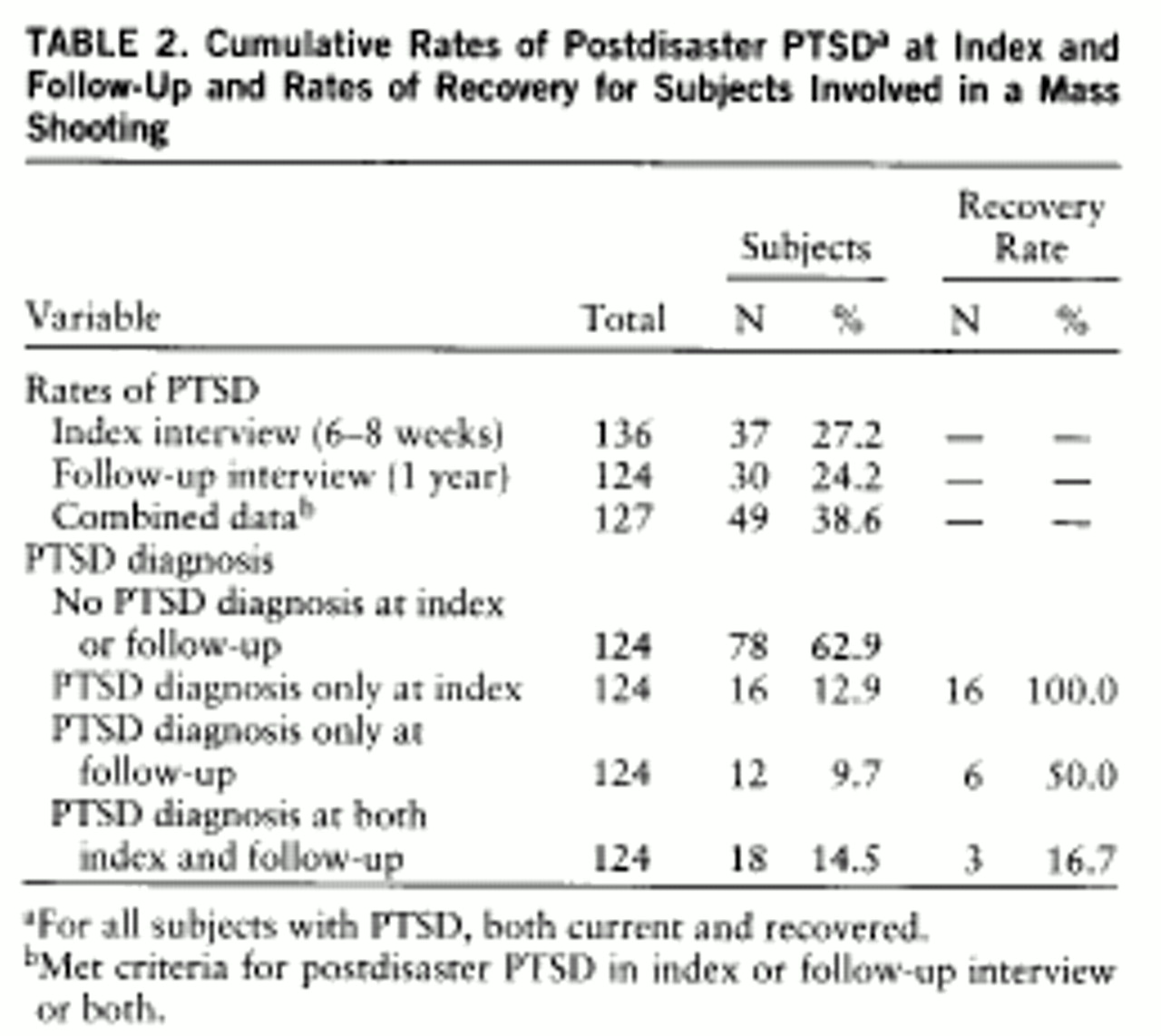

Table 2 presents rates of cumulative postdisaster (i.e., specific to the cafeteria shooting) PTSD obtained at index and follow-up and summarizes data describing rates of recovery. At follow-up, three of the 37 subjects meeting criteria for disaster-related PTSD at index were among those not reinterviewed. At follow-up, three individuals without PTSD at index interview reported having PTSD at index. Twelve subjects with new cases of disaster-related PTSD were identified. Of these, six indicated that they had already recovered, and six still had active PTSD. Of all 46 subjects with PTSD identified at index or follow-up and interviewed at both time points, 25 (54%) reported that they were recovered at follow-up. Of the 19 individuals with PTSD at index who were identified as recovered at 1 year, on the follow-up interview 16 (84%) failed to meet criteria at any time for PTSD related to the shooting. Therefore, the great majority of subjects with PTSD at index who had apparently recovered at follow-up were not detected at reinterview because they either did not remember or for some other reason did not report enough symptoms to indicate that they had ever suffered from PTSD after the disaster. Because so few subjects who recovered reported having had PTSD, it is not possible to report systematic information on their course of recovery during the months of the year's follow-up.

Rates of disaster-related PTSD (experienced at any time since the disaster) at index and follow-up interviews were 27% and 24%, respectively. Although these rates are quite similar, further inspection reveals considerable discrepancy as to which subjects reported PTSD at either interview. (Assessment of disaster-related PTSD at follow-up ascertained the presence of PTSD at any time after the disaster. Therefore, subjects who reported postdisaster PTSD at index but no history of disaster-related PTSD at follow-up were considered discrepant in their reporting.) The kappa coefficient for the reliability of postdisaster PTSD diagnosis at index and follow-up was only 0.41. Disaster-related PTSD diagnoses among 28 subjects (21% of the entire group) were discrepant between index and follow-up. Overall, 61% of all 46 disaster-related cases of PTSD identified at either interview represented inconsistent diagnoses. Although only 15% of all subjects met criteria at both times, combining all cases of PTSD at both interviews yielded an overall disaster-related PTSD rate of 39%. Further information detailing symptom levels in relation to discrepancies in the PTSD diagnosis between index and follow-up with respect to the diagnostic criteria will be provided later in this document.

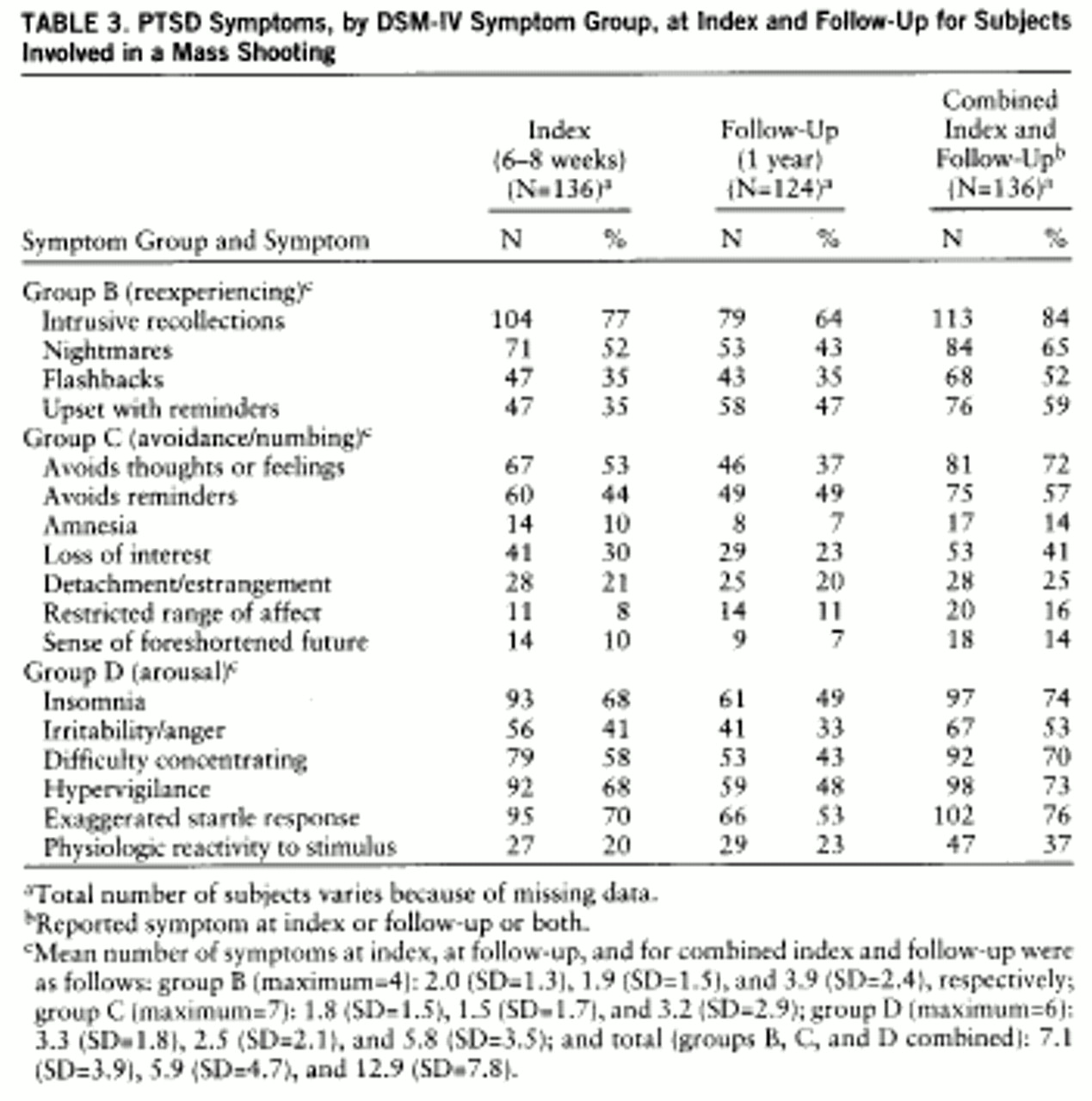

Table 3 presents index and follow-up data on individual symptoms of disaster-related PTSD. The most frequently endorsed symptom on both interviews, as well as overall, was intrusive recollections, which was acknowledged by 84%. The second most prevalent symptom both at index and follow-up, as well as overall, was exaggerated startle reflex (76%). Insomnia was a close third (74%) in frequency. No symptom showed significantly higher prevalence at follow-up than at index.

Table 3 also presents rates of disaster-related PTSD symptoms by symptom group at index and follow-up. Group D (arousal) symptoms were most prevalent and group C (avoidance/numbing) least prevalent at both interviews. Absolute numbers of reported symptoms, particularly group D (arousal) symptoms, were lower at follow-up than at index.

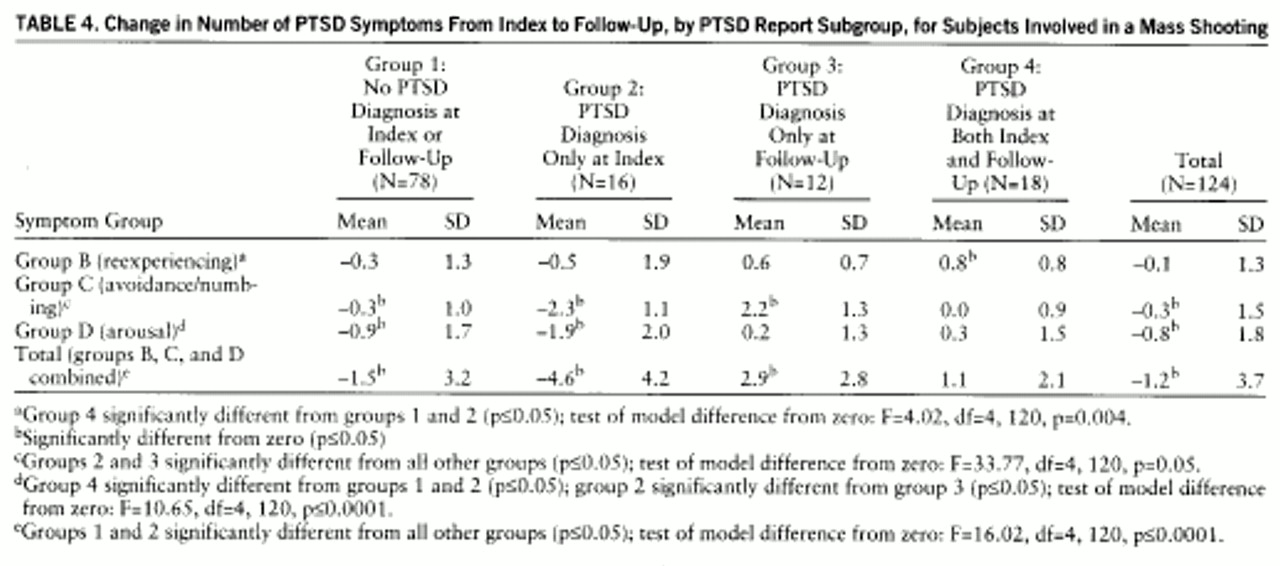

For further data analyses, study subjects were divided into subgroups according to assignment of disaster-related PTSD diagnoses at index and follow-up. These subgroups included 78 subjects (63%) who did not have a diagnosis of PTSD at index or follow-up, 16 (13%) who had a PTSD diagnosis only at index, 12 (10%) who had a PTSD diagnosis only at follow-up, and 18 (15%) who had PTSD diagnoses at both interviews. Of the 46 subjects with PTSD identified at either interview who were interviewed at both times, 12 (26%) were not identified at index and 16 (35%) were not identified at follow-up.

Table 4 presents data on change in number of disaster-related PTSD symptoms by symptom group, separately for index and follow-up diagnosis subgroups. Group B (reexperiencing) symptoms changed the least of any symptom group. Number of group C (avoidance/numbing) symptoms changed considerably from index to follow-up for both subjects who had a PTSD diagnosis only at index and subjects who had a PTSD diagnosis only at follow-up. Number of group D (arousal) symptoms dropped considerably from index to follow-up for the subgroup reporting PTSD only at index. Those who had a PTSD diagnosis only at index recalled an average of 4.6 fewer symptoms at follow-up than at index, and those who had a PTSD diagnosis only at follow-up reported on average 2.9 additional symptoms at follow-up.

Half (53%) of subjects reporting disaster-related PTSD at follow-up identified initial onset of symptoms the day of the incident, and most others (40%) reported onset in the week after the incident. One subject (3%) reported onset in the month after the incident, and another (3%) later in the first 6 months after the event. Therefore, none of the 12 newly identified PTSD cases at follow-up was of delayed onset (more than 6 months).

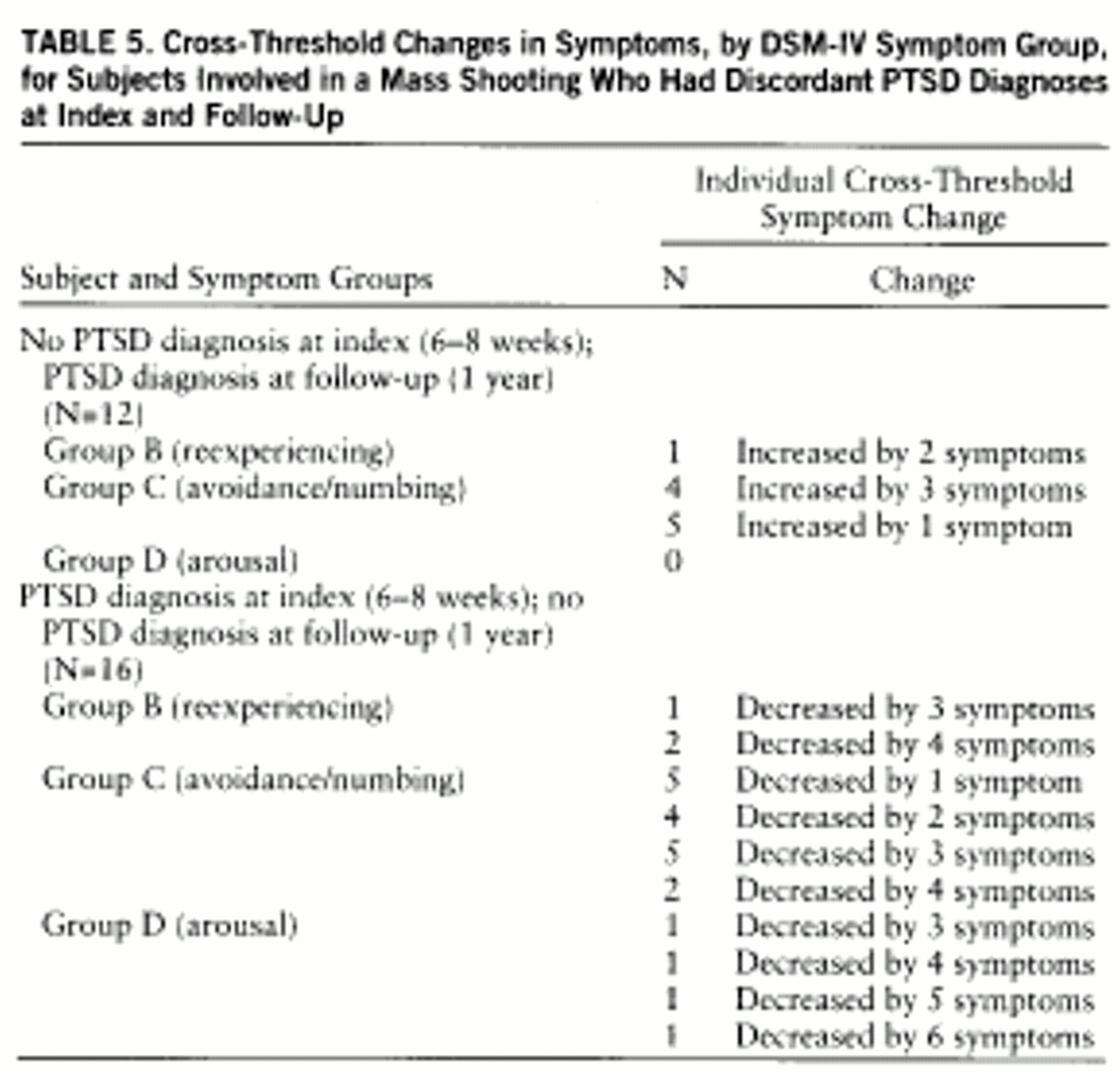

Table 5 lists the changes in number of symptoms reported by those who crossed the critical symptom thresholds for the diagnosis of PTSD between index and follow-up. The subgroup of 12 who had PTSD only at follow-up evidenced no change in group D (arousal) symptoms, and little change in group B (reexperiencing) symptoms. The majority of increases occurred in group C (avoidance/numbing) symptoms. (Two subjects who had PTSD only at follow-up had no increase in number of symptoms at follow-up; their diagnosis of PTSD was due to an increase in time and/or functional severity criteria.) The subgroup of 16 who reported PTSD at index but not at follow-up showed cross-threshold changes in all three symptom groups, with the greatest change occurring in group C (avoidance/numbing) symptoms. Overall, half the cross-threshold changes in the group that had PTSD only at follow-up were accounted for by an increase of one symptom. In the group reporting PTSD at index but not at follow-up, however, only a minority (five of 23) of threshold transitions was accounted for by a decrease of one symptom.

Other diagnoses also showed inconsistencies between index and follow-up (when subjects who were interviewed at both times were counted). Of 23 cases of all postdisaster major depression identified at either index or follow-up, 13 (57%) were identified at index and 17 (74%) at follow-up (kappa=0.39). Of 11 cases of postdisaster alcohol use disorder identified at index or follow-up, only five (45%) were identified at index and all 11 at follow-up (kappa=0.46). Of 34 non-PTSD postdisaster diagnoses identified, 22 (65%) were identified at index and 25 (74%) at follow-up (kappa=0.45).

A series of bivariate analyses was performed to predict postdisaster disorders (total diagnoses identified in both interviews, current psychiatric disorder at follow-up, and recovery from PTSD) from independent predictor variables of diagnosis (predisaster and acute postdisaster), demographic characteristics (gender, age, race, education, and marital status), and disaster exposure subgroup (classified categorically as injured, noninjured eyewitness, witnessed aftermath only, on site but not direct witness, and associated but not on site). Total rate of disaster-related PTSD (including all cases identified at index or follow-up or both) for women (47%) was higher than that for men (29%) (χ2=4.44, df=1, p=0.03). No other demographic variables predicted PTSD or any other disorder, and disaster exposure subgroup was not associated with any disorders. Among individuals without comorbid psychopathology, no demographic variables aside from gender predicted PTSD.

PTSD was associated with other psychopathology. Considering the total of all cases of PTSD detected in either interview, three-fourths (76%) of women with a predisaster diagnosis at index developed PTSD at some time after the disaster, compared to only 34% of women without a diagnosis (Pearson χ2=10.35, df=1, p=0.001). This relationship was not significant for men (33% compared to 25%) (Pearson χ2=0.50, df=1, p=0.48). Acute postdisaster comorbid psychiatric illness at index also predicted PTSD: 83% of subjects reporting another acute postdisaster diagnosis at index reported disaster-related PTSD at some time after the disaster, compared with 28% of those without another identified disorder at index (Pearson χ2=25.01, df=1, p=0.001). Report of any diagnosis at any time (before the disaster, after the disaster, or follow-up) was associated with development of PTSD: 61% of subjects reporting another lifetime disorder developed PTSD, compared to 31% of others (Pearson χ2=9.13, df=1, p=0.003). Forty-one percent of subjects who developed disaster-related PTSD at any time after the disaster had a lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorder.

Major depression was the one diagnosis that was consistently associated with PTSD. Predisaster depression was associated with any report of postdisaster PTSD, which developed in 75% of subjects with a history of depression, compared with only 33% of those without it (Pearson χ2=10.25, df=1, p=0.001). Report of major depression at index predicted PTSD, which developed in 100% of subjects with index depression and 31% of those without it (Pearson χ2=25.05, df=1, p=0.001). Report of lifetime depression was associated with development of PTSD: 81% of subjects with any depression developed PTSD, compared with 32% of others (Pearson χ2=14.06, df=1, p=0.001).

No diagnostic or demographic variable predicted recovery from PTSD at follow-up. Subjects who recovered from PTSD did not report significantly fewer symptoms at index than those who did not recover.

The group that reported PTSD at follow-up but not at index reported marginally higher rates of predisaster psychiatric diagnosis (67% versus 35% of others; Fisher's exact p=0.06), but no other diagnostic or demographic variables characterized this group. Membership in the group reporting PTSD at index but not at follow-up was not associated with any diagnostic or demographic variable.