The diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple personality disorder) is usually not made until adulthood (

1), long after the extreme maltreatment thought to engender the condition has passed. Therefore, although there is a consensus that the most common cause of the disorder is early, ongoing, extreme physical and/or sexual abuse (

2–

6), accounts of such abuse are usually provided retrospectively by the patient and lack objective verification. As Putnam (

1) said, “In most reports, including the NIMH survey, there is no outside verification that any trauma actively occurred.”

Coons (

7) recently attempted to verify abuse histories in a group of 19 children and adolescents through interviews with families and “collateral reports from numerous sources.” The extent to which abuse was documented in each case was unclear. Because neither the symptoms nor the abuse engendering them have ever been documented objectively in a group of dissociative identity disorder patients of any kind (children, adolescents, adults, or murderers), both the diagnosis and its etiology in childhood maltreatment have met with criticism ranging from skepticism to scorn (

8–

15).

The diagnosis in felons is doubly suspect. The prospect of facing the consequences of a serious offense invites malingering (

16,

17). Dinwiddie and colleagues (

18) asserted that the disorder, especially in forensic cases, could not be distinguished from malingering. Orne and colleagues (

19) suggested that the most objective means of making the diagnosis in forensic cases was through interviews with family members and others who had observed the characteristic behavioral changes in the individual before he or she had committed a particular offense. To date, however, there have been no such systematic studies of groups of felons with dissociative identity disorder or, for that matter, of any other series of adult patients with the disorder. Carlisle (

20) described 13 murderers suffering from multiple personality disorder but provided few objective data to support the diagnosis or its etiology. Coons (

21) collected information on a group of 18 murderers alleged to have suffered from multiple personality disorder; his data were gleaned in great measure from newspaper accounts and legal decisions. For lack of objective documentation of symptoms or abuse, in most instances the diagnosis was disbelieved.

= Given the dearth of objective documentation of dissociative symptoms and the antecedent abuse that engenders dissociative identity disorder, we welcomed the opportunity to present objective data on dissociation and abuse in 12 murderers suffering from the disorder. As will be discussed, we believe that our findings are also relevant to cases of the disorder in adults who have not committed violent crimes.

METHOD

During a 13-year period in the 1980s and 1990s, the first author (D.O.L.) had the opportunity to do psychiatric evaluations of approximately 150 murderers. Of these murderers, 29 were subjects in a study of death row inmates. The majority of the rest were evaluated at the request of individual defense attorneys. Several others were evaluated at the request of the court, of prosecutors, or of family members. Of these murderers, 14 met the DSM-IV criteria for dissociative identity disorder. We were able to obtain objective documentation of both child abuse and long-standing dissociative signs and symptoms in 11 of these 14 individuals and of early dissociative signs and symptoms in a 12th. This report focuses on the 12 murderers with dissociative identity disorder for whom objective, confirmatory data on child abuse and/or long-standing dissociative symptoms could be verified. There were 11 men and one woman. Their ages at the time of their offenses averaged 28 years (range=15–44). Eight were white and four were black.

The subjects' psychiatric, neurologic, medical, social service, welfare, school, probation, police, prison, and military records were reviewed, and in eight cases social service, medical, psychiatric, military, court, or police records pertaining to parents were also reviewed. Any evidence of abuse, neglect, and/or dissociative signs and symptoms was noted and tabulated.

All 12 subjects had been evaluated psychiatrically by the first author (D.O.L.), a board-certified psychiatrist. Nine had been examined neurologically by one of the authors (J.H.P.), a board-certified neurologist; a 10th was examined by another board-certified neurologist. An 11th, at age 2, had been evaluated by a neurologist, at which time an EEG was performed. The psychiatric and neurologic reports of these evaluations were reviewed. The nature of the psychiatric and neurologic evaluations and the criteria for specific signs and symptoms have been described elsewhere (

22–

25). During these psychiatric evaluations, dissociative phenomena were explored in detail and included questions about trances, time loss, fugues, amnesias, imaginary companions, rapid mood shifts, auditory/visual hallucinations, fluctuations in skills, being blamed for disavowed acts, sounding/acting like a different person, and using different names/signatures/handwriting. Records of these neuropsychiatric evaluations and of any previous evaluations were reviewed for the presence or absence of the above-mentioned signs and symptoms. Handwriting samples (e.g., old journals, letters) were also examined. These written materials were produced before the subjects' psychiatric evaluations and thus were not influenced by the examiner. In all cases, affidavits, testimony, and/or reports of interviews with family members, friends, neighbors, childhood acquaintances, teachers, probation officers, police, and clergy were reviewed for mention of the signs and symptoms and for any indications of abuse and neglect.

At the time of publication of this article, clinical data regarding symptoms and abuse histories were in the public domain (i.e., in trial transcripts, exhibits, appeals briefs, newspaper articles, and books); hence, informed consent to tabulate data was not necessary. Nevertheless, out of respect for the privacy of the subjects and their families, we have not identified the subjects by name.

RESULTS

Signs and Symptoms of Dissociative Identity Disorder

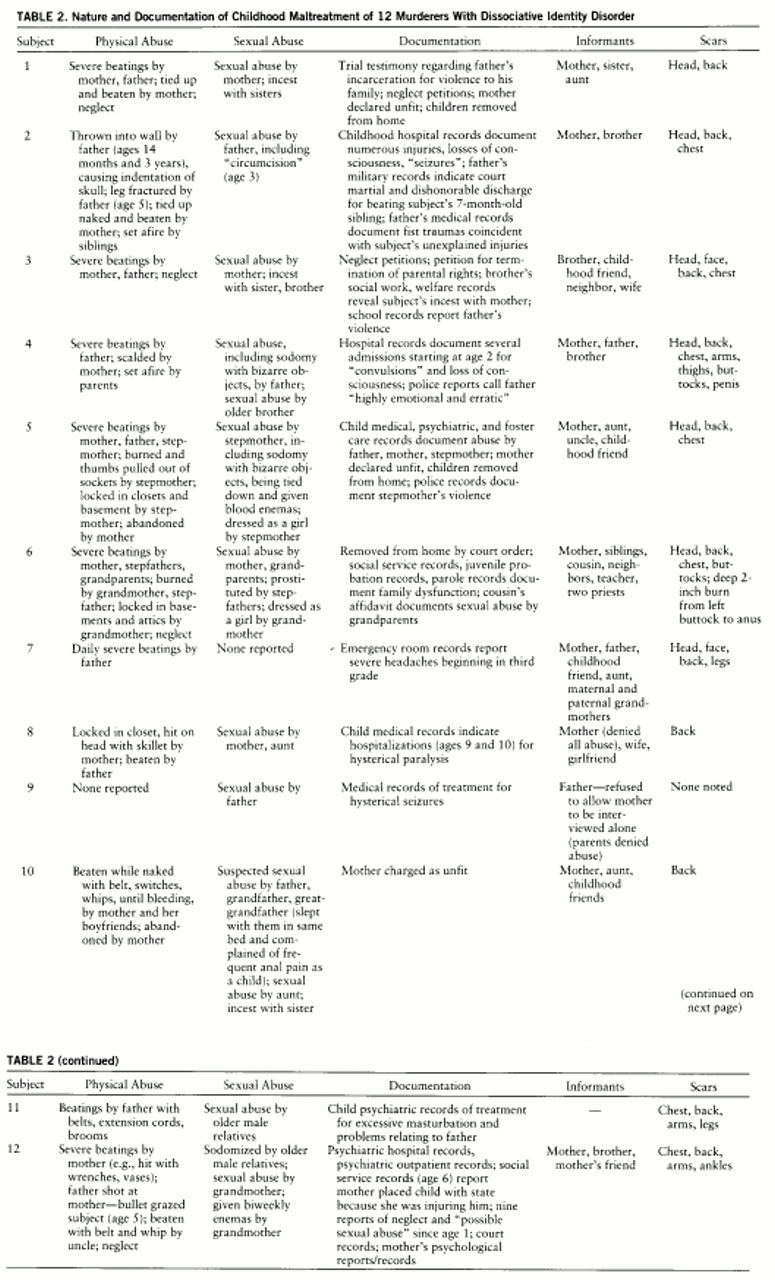

Table 1 presents the subjects' dissociative symptoms in childhood and adulthood and the corroborative documentation. Among the most common symptoms and signs were trances, amnesias for circumscribed periods of time and/or particular behaviors, changes in voice and demeanor, and auditory hallucinations.

As can be seen in

table 1, the amounts of information available on the subjects' childhoods varied. We were able to obtain objective evidence that during childhood, eight of the 12 subjects had trances and amnesias, nine had experienced auditory hallucinations, and 10 had vivid and long-standing imaginary companions who seemed to be precursors of their alternate personality states.

Ten subjects experienced trance-like states in adulthood that were also observed by others. Two described their ability to remove themselves from situations as “astral projection.” Others described their trance-like states as blanking out, spacing out, or transporting themselves to imaginary places in their heads. Seven reported being able to block out physical pain.

All 12 subjects, as adults, had impaired memory for both violent and nonviolent behaviors. For example, subject 5 pulled out his own toenails at night and, in the morning, did not know how this had happened. Subjects 4, 5, and 11, all of whom had female alternate personalities, found women's clothing in their possession and did not know how it got there. Subject 4, at trial, insisted that the bloodstained suit he had been wearing at the time of his arrest belonged to someone else because it was too big to be his.

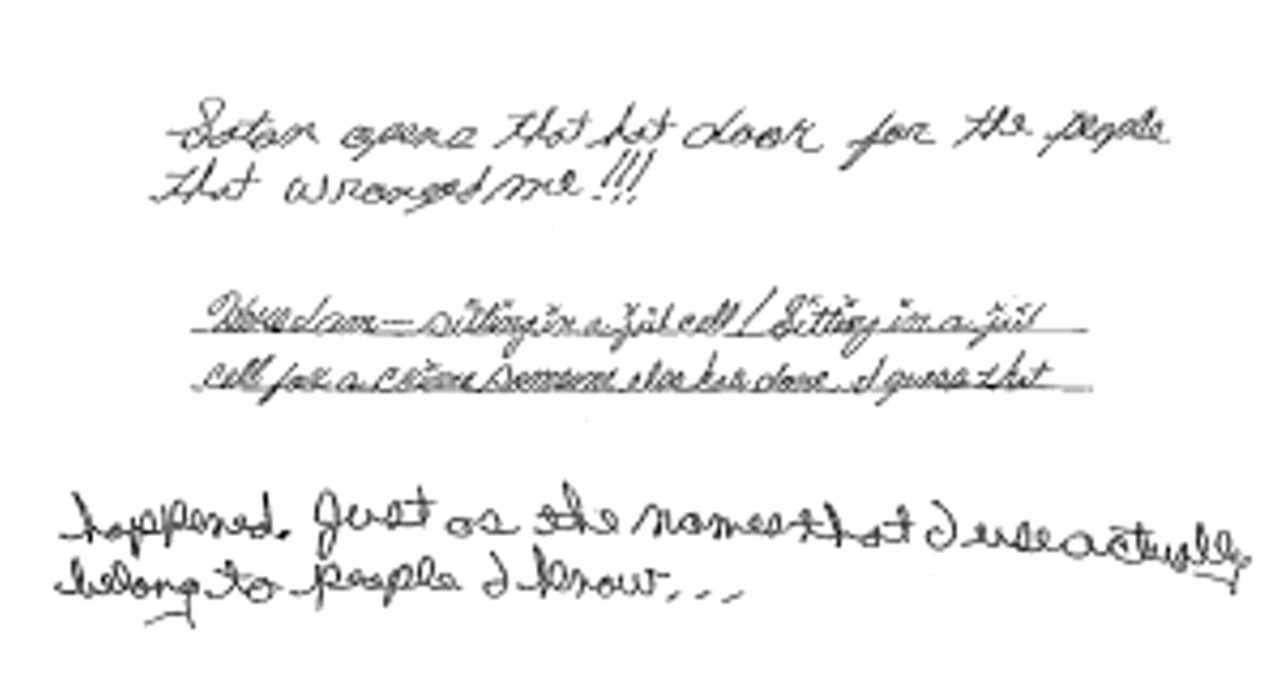

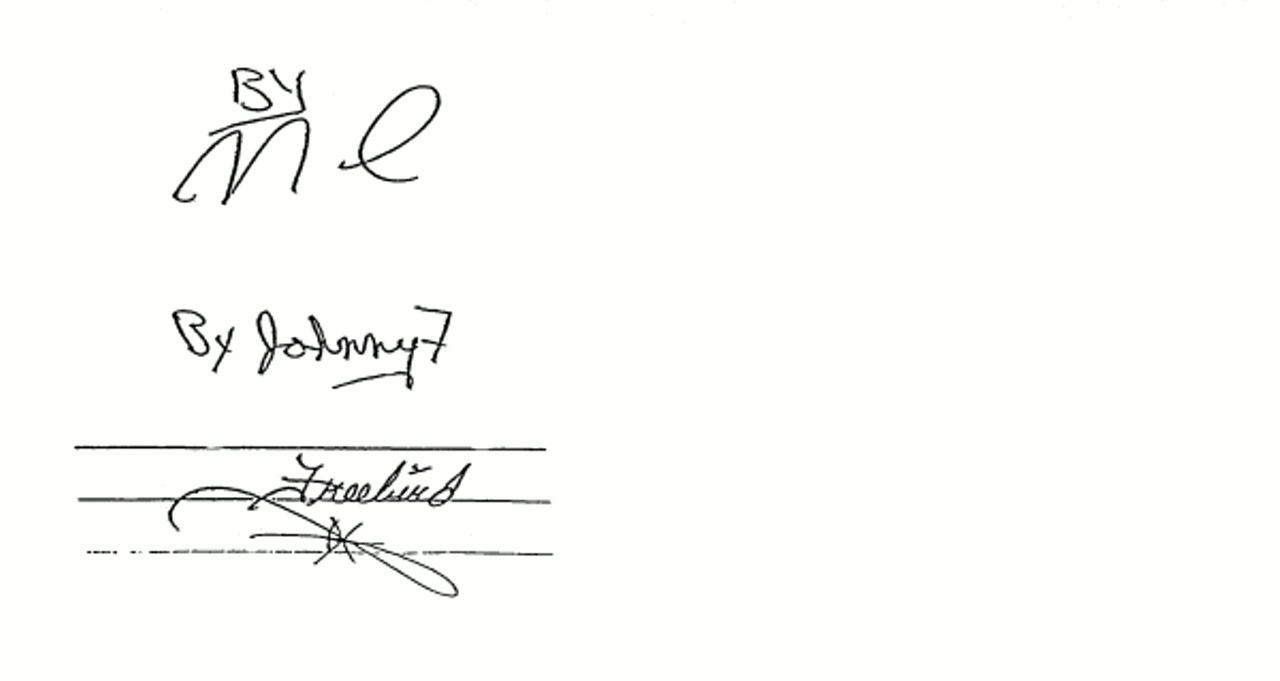

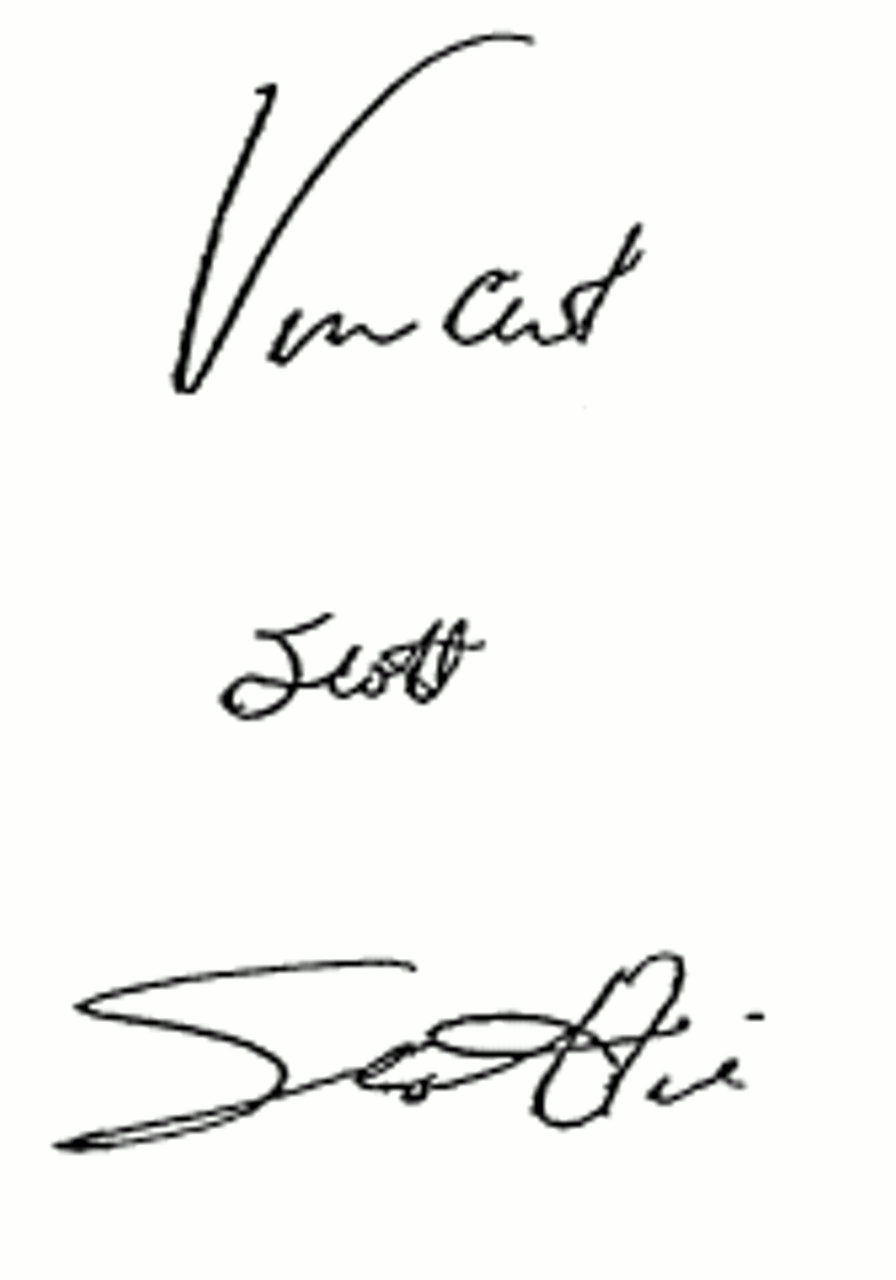

All 12 subjects were described by others as having voice changes and/or marked changes of demeanor. For example, three people reported that subject 9, the only woman in the study group, periodically sounded like an aggressive male, and male subjects 4 and 11 at times reportedly sounded like women. Subjects 5 and 6 were noted to have alternate personality states with different visual acuities, and the lawyers for subject 4 reported that he did not recognize his own voice on tape-recorded police interviews and insisted it was the voice of someone else. All 12 subjects had used different names at different times, not in the context of avoiding arrest or responsibility. Writing samples obtained from 10 subjects revealed markedly different handwritings.

Figures 1,

2,

3, and

4 are examples of the different signatures and handwritings of three of these 10 subjects.

All 12 subjects had histories of experiencing auditory hallucinations that, during psychiatric evaluation, were recognized by the examiner as being voices of alternate personalities. Seven experienced severe headaches when they heard arguments in their heads among alternate personalities. Subject 1 pulled out his own teeth in an unsuccessful effort to cure his excruciating headaches.

In all cases, examiners were able to speak with at least one alternate personality. The subjects averaged three to four personality states (the range was one to seven). These figures may be underestimates because of the limited time available for evaluations. Nine subjects (including our only female subject) had violent male alternate personalities, most of whom said they “took the pain.” Six male subjects had older female alternate personalities whose functions were caretaking, comforting, and protecting. Of note, five subjects had alternate personalities who were embodiments of parents or relatives; two had abusive father personalities, one had an abusive mother personality, one had a powerful aunt personality, and one had a sister personality. The nature and function of these alternate personalities and their relevance to the crimes committed will be described in a subsequent paper.

Table 1 lists the sources of information confirming evidence of dissociative identity disorder in each subject. As can be seen, documentation regarding subjects' dramatic changes of voice and/or demeanor came not just from family members but also from police records, notes of a legal assistant, observations of a jail guard, observations of a prosecution psychiatrist, and subjects' co-workers, roommates, acquaintances, and friends. As mentioned, objective documentation of personality changes in the form of different handwriting and signatures could also be found in the journals, letters, and documents of 10 subjects.

The Nature of Maltreatment in Childhood

Because the histories of abuse of both patients with dissociative identity disorder and murder suspects are often questioned, we call special attention to

table 2, which presents objective documentation of the nature and extent of physical and sexual abuse of 11 of our 12 subjects. The term “abuse” does not do justice to the quality of maltreatment these individuals endured. A more accurate term would be “torture.” For example, subject 4 was deliberately set on fire by his parents. Subject 6 was used in child pornography by stepfathers and was deeply scarred from anus to mid-buttock from having been made to sit on a stove burner. At 3 years of age, subject 2 had his penis scalded and “circumcised” by his father. Subject 5 was tied down by his stepmother, given enemas allegedly containing blood, and, to stanch the blood, had tampons inserted into his rectum, thus simulating menstruation. This subject was removed from one foster family because he had been caught molesting other children and wearing girls' underwear and sanitary napkins.

We were surprised to find that in their usual personality states, most subjects denied or minimized childhood maltreatment. Four of them, for whom documentation of extraordinary abuse was discovered, totally denied any physical or sexual abuse. Seven others who had been severely physically and/or sexually abused had but fragmentary memories of the abuse. None attempted to use histories of abuse to enlist the sympathy of jurors or to excuse their violent acts. Since in their usual personality states most of the subjects had no idea of the kinds of maltreatment they had sustained, they could not use histories of abuse to manipulate clinicians or anyone else.

Histories of maltreatment were obtained primarily from old records, accounts provided by first-degree relatives, and the reminiscences of childhood friends. For example, subject 3 had no recollection of his incestuous relationship with his mother; information regarding incest was gleaned from the social service records of his brother. Similarly, subject 6 knew nothing of the sexual abuse sustained at the hands of his grandparents. The affidavit of a cousin who lived with him during childhood—a document discovered by one of the authors (D.O.L.) after the subject had been executed—revealed that his grandmother had dressed him as a girl and given him to his grandfather to be used for sexual gratification.

Before evaluation none of the subjects was aware that he or she suffered from dissociative identity disorder, and most remained ignorant of their condition after their psychiatric evaluations. Even after some were told of their condition, they tended to disbelieve it. For example, when subject 4 learned of his diagnosis at a court hearing, his response was, “I think you're full of shit.” Of note, in this case, because of his dramatically changing demeanor during incarceration, the subject's fellow prisoners had made the diagnosis of multiple personality disorder years before the psychiatrist ever saw him.

DISCUSSION

Our ability to interview subjects' family members and friends, our access to their past psychiatric, social, and educational records, and our access to their personal letters and diaries enabled us to document evidence of long-standing dissociative symptoms in all 12 of our subjects and to obtain objective evidence of extreme abuse of 11 of them. Rarely, if ever, do psychiatrists have the opportunity to obtain this quantity and quality of confirmatory data about adults with dissociative identity disorder. It was only because of the time-consuming investigations conducted in the course of the legal representation of these murderers that we could amass these kinds of data.

Contrary to Dinwiddie and colleagues (

18), we have demonstrated that dissociative identity disorder can be differentiated from malingering and other disorders. The evidence of strikingly different handwriting styles

antedating the murders in question, plus the documentation of amnesias and of changes in voice, demeanor, and appearance observed by family members and others

before our subjects' crimes, settles once and for all the issue of malingering in these cases. To have malingered, our subjects would have to have planned their murders long in advance and feigned their early symptoms in anticipation of some day committing a violent crime, a highly unlikely scenario. In short, with adequate data, it is possible to distinguish dissociation from malingering and from other disorders. For example, although dissociative identity disorder shares certain symptoms with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other syndromes, none of these other disorders is characterized by the voice, demeanor, and handwriting changes and amnesias characteristic of dissociative identity disorder, as documented in our study group.

The question remains: to what extent are our 12 murderers with dissociative identity disorder representative of other adults with the disorder? After all, most patients with the disorder do not commit murder. On the other hand, most patients with the disorder do have aggressive, protector personality states (

1,

5). However, relatively few commit violent crimes, reflecting, at least in part, the fact that most recognized cases of dissociative identity disorder occur in women (

1,

26,

27), and women as a group are far less violent than men (

28). Whereas Loewenstein and Putnam (

26) reported that similar percentages of men and women among their subjects with multiple personality disorder had “homicidal alters” (35% versus 32%), 19% of the men and only 7% of the women reported actually having committed murder. In our own clinical experience, we found that among the male outpatients seeking treatment for dissociative identity disorder at our clinic, a substantial percentage (64%) had demonstrated rageful behaviors that came just short of homicide. In fact, one patient reported spending time in a reformatory after committing murder, and two others had been arrested for attempted murder. A much smaller percentage of the women in our clinic group (9%) were similarly aggressive. One had attempted to shoot her adult son, and another had tried to push her father in front of a car.

The majority of the males with dissociative identity disorder that we have seen have not been clinic outpatients but, rather, have been examined in prisons, where they were incarcerated for violent crimes. On the basis of our clinical experience, we suspect that the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder is overlooked in males more often than it is in females because the violent behaviors of the protector alternate personality states of men go unrecognized and their violence is regarded instead as “sociopathy.” As a result, males with the disorder are far more likely than their female counterparts to be arrested and incarcerated.

The 12 murderers in our study were unaware of their psychiatric condition. They also had partial or total amnesia for the abuse they had experienced as children. Such is the nature of dissociative identity disorder. Contrary to the commonly held assumption that individuals facing the consequences of murder charges will exaggerate their childhood misfortunes, these murderers could barely remember anything about their childhoods. What is more, contrary to the popular belief that probing questions will either instill false memories or encourage lying, especially in dissociative patients, of our 12 subjects, not one produced false memories or lied after inquiries regarding maltreatment. On the contrary, our subjects either denied or minimized their early abusive experiences. We had to rely for the most part on objective records and on interviews with family and friends to discover that major abuse had occurred.

Even if the subjects had been able to provide memories of maltreatment and even if they had been aware of their diagnosis, because we were dealing with two problematic issues—murder and dissociative identity disorder—it was vital that we document from outside sources as much objective evidence as possible of dissociative symptoms and childhood maltreatment. We did this. In every case, three or more outside sources provided independent evidence of subjects' marked changes in voice, demeanor, and behavior, and in 11 cases abuse was also verified objectively. Furthermore, in 10 cases handwriting samples produced before the offenses in question documented changes in writing styles and signatures. Thus, the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder and the history of abuse did not rest exclusively or even primarily on reports obtained from a subject.

The extent to which it was possible in these murder cases to review old records, interview families, and obtain objective documentation of symptoms and early abuse was, of course, unusual. In most cases of dissociative identity disorder, this degree of verification is not possible. Nevertheless, our experience with these 12 murder cases illustrates that with sensitivity, diligence, and appropriate resources, corroborative external evidence of prior dissociative symptoms and of early, extreme abuse in adult patients with dissociative identity disorder is there to be found. We may not always be able to obtain this extensive a body of documentation for all of our patients, but we must try.